Push and Poll: How Search Engines Reflected and Relegated Polish State-Backed Media in the 2023 Election

Our research shows that the studied search products provided a far more pluralistic media environment than traditional media in Poland. Poland’s disproportionately large and influential state-controlled and state-captured media outlets did not translate to significant influence over search results, with approximately 7% of all search results emanating from such sources, dipping as low as 5% on Google Search. News aggregators on search platforms—devoid of the balancing effect of non-media sites—showed higher presences of state-backed media: 8.4% on Bing News and 8.7% on Google News. Still, given 70% of Poles get news from television and Telewizja Polska (TVP) is Poland’s most watched broadcaster, monitored search environments seemed to expose Polish audiences to a diversity of outlets not available via more traditional mediums.

Table 1. Total Volume of Polish State-Controlled or State-Captured Domains on Google and Bing

|

Search Platforms |

State-Captured |

State-Controlled |

Total Results |

% Search Results |

|

Google News |

540 |

1,091 |

1,631 |

8.7% |

|

Bing News |

1,028 |

551 |

1,579 |

8.4% |

|

Bing |

511 |

900 |

1,411 |

6.9% |

|

|

311 |

838 |

1,149 |

5.0% |

|

Total |

2,390 |

3,380 |

5,770 |

7.2% |

The exception was searches about refugees, immigration, and other topics related to external influences. For example, a Polish voter running searches on Google News during our studied period for “German Influence”, “Russian Influence”, or “Election Interference”—wpływy niemieckie, wpływy rosyjskie, and inferencja w wybory, respectively—would have encountered, on average, Polish state-backed media in three of the top ten results, and state media as the top result roughly 33% of the time. By contrast, search queries related to topics surrounding the Ukraine war, COVID-19, or domestic social issues, namely LGBTQ and women’s rights, escaped significant state media penetration on search engines, with roughly one in thirty results from state-backed media.

About “State-Controlled”, “State-Captured”, and “Independent” Media

State-Controlled”, “State-Captured”, and “Independent” reflect the degree of government influence over media outlets and their ability to operate without external interference. These definitions are derived from the State Media Monitor, a project of the Media & Journalism Research Center.

- “State-Controlled” media are owned or directly managed by the state and usually support the government’s viewpoint.

- “State-Captured” media were once independent but have since come under substantial state ownership, funding, or editorial direction.

- “Independent” media maintain financial and editorial autonomy, free from direct state control.

In this report, state-backed is used to refer to state-controlled and state-captured media collectively.

Backsliding in Poland’s media ecosystem

Since 2015, Poland’s information ecosystem has been characterized by a stark decline in media freedom and pluralism. Within months of coming to power in 2015, Poland’s Law and Justice (PiS) party took control of public media by neutering the constitutionally mandated regulator that oversees public TV and radio and replacing it with a new council made up of PiS loyalists. Since then, the state broadcaster TVP has served as a PiS government mouthpiece, regularly running smear campaigns against figures that disagree with PiS’s policies and portraying vulnerable groups, including migrants and the LGBTQ community, as threats to the Polish state. This media bias and hostile rhetoric has been most noticeable during election cycles. The Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) election observation missions found that public media bias gave PiS a clear electoral advantage in both the 2019 parliamentary and 2020 presidential elections. OSCE observers also noted that both election campaigns were tarnished by xenophobic, homophobic, and anti-semitic rhetoric by PiS, which the public broadcaster TVP subsequently echoed.

In addition to its takeover of public media, PiS has subverted media pluralism in its campaign to “repolonize” private media by reducing foreign ownership. In December 2020, the state oil giant PKN Orlen acquired the previously German-owned Polska Press—a media consortium with a readership of over 17 million across its 20 regional daily newspapers, 120 regional weekly newspapers, and 500 online portals. Within eight months of the acquisition, 14 of the 15 editors-in-chief of the regional dailies stepped down under pressure and were replaced by employees from the state broadcaster or other right-wing media supportive of PiS. Numerous other deputy editors and journalists also left. A 2023 report by the Helsinki Foundation for Human Rights showed that, in a little over a year, the takeover had negatively impacted journalists’ rights and led to editorial shifts favorable to PiS. PiS also attempted to pass a law that would block companies from outside the European Economic Area from having majority ownership of Polish media outlets. Many viewed the bill as an attempt to silence Poland’s largest independent television broadcaster and a prominent critic of PiS, TVN, owned by the US-based company Warner Bros. Discovery (formerly Discovery, Inc.). The bill was vetoed by the Polish president following pressure from the United States.

Lastly, the government heavily influences the Polish information space through financial benefits. Independent media outlets favorable to PiS—including Fratria media group (owner of the newspapers W Polityce and W Gospodarce), Gazeta Polska (owner of Niezalezna), and Radio Maryja—acquire revenue from advertisements by state-controlled companies. Revenues from these advertisements account for three-quarters of these group’s profits, while more critical outlets have suffered a corresponding drop in advertising revenue and a sharp decline in subscriptions from government ministries.

Table 2. Polish state-backed domains with more than 25 occurrences across on Google and Bing

|

Domain |

Bing |

Bing News |

|

Google News |

Total |

% of Search Results |

|

pap.pl |

324 |

256 |

267 |

399 |

1,246 |

1.55% |

|

tvp.info |

364 |

68 |

202 |

273 |

907 |

1.13% |

|

polskieradio24.pl |

140 |

139 |

162 |

362 |

803 |

1.00% |

|

wpolityce.pl |

216 |

245 |

50 |

144 |

655 |

0.81% |

|

niezalezna.pl |

73 |

346 |

40 |

61 |

520 |

0.65% |

|

polskieradio.pl |

63 |

88 |

114 |

42 |

307 |

0.38% |

|

i.pl |

28 |

15 |

76 |

114 |

233 |

0.29% |

|

dziennikzachodni.pl |

33 |

90 |

6 |

10 |

139 |

0.17% |

|

wgospodarce.pl |

5 |

15 |

35 |

55 |

110 |

0.14% |

|

belsat.eu |

34 |

27 |

36 |

97 |

0.12% |

|

|

pomorska.pl |

18 |

38 |

2 |

33 |

91 |

0.11% |

|

dzienniklodzki.pl |

7 |

36 |

7 |

16 |

66 |

0.08% |

|

nto.pl |

14 |

24 |

5 |

16 |

59 |

0.07% |

|

nowiny24.pl |

5 |

42 |

5 |

7 |

59 |

0.07% |

|

poranny.pl |

10 |

30 |

17 |

|

57 |

0.07% |

|

dziennikbaltycki.pl |

27 |

20 |

8 |

55 |

0.07% |

|

|

kurierlubelski.pl |

1 |

38 |

|

10 |

49 |

0.06% |

|

dziennikpolski24.pl |

15 |

27 |

3 |

2 |

47 |

0.06% |

|

tvpparlament.pl |

|

|

47 |

|

47 |

0.06% |

|

gazetakrakowska.pl |

17 |

21 |

7 |

45 |

0.06% |

|

|

lublin.tvp.pl |

1 |

|

27 |

13 |

41 |

0.05% |

|

gloswielkopolski.pl |

22 |

17 |

39 |

0.05% |

What issues dominated the 2023 election?

Like other elections in recent years, polarizing issues dominated the 2023 parliamentary election cycle. Just two months before the election, PiS announced that the ballot would also include a controversial four-question referendum. Two of the four questions asked loaded questions about PiS’s anti-migrant policy, including whether Poland should admit “illegal immigrants” from North Africa and the Middle East, as “imposed” by the EU migration pact, and if it should remove the border wall with Belarus that was erected in 2022 to prevent illegal immigration in the aftermath of the Belarus-EU border crisis. The other two questions related to the sale of state assets to foreign entities and raising the retirement age. As documented by OSCE observers, the referendum questions built on PiS’s past tactics to amplify hostile rhetoric during election cycles about groups that “threaten” Polish identity, such as migrants and the LGBTQ community.

Support for Ukraine was also a focal point. Although Poland was one of Ukraine’s staunchest allies after Russia’s full-scale invasion in February 2022, relations between the two countries have slowly dwindled since. This worsening of relations is best illustrated by Warsaw and Kyiv’s grain dispute. Shortly before the election the Polish government banned Ukrainian grain imports. This ban was prompted by domestic pressures to combat an influx of cheap Ukrainian grain that is typically exported globally, but, due to the war, had flooded Polish markets creating increased competition. Kyiv subsequently filed a lawsuit against Poland at the World Trade Organization. In response, PiS leaders stated that Poland would stop sending weapons to Ukraine and compared the country to a “drowning person” clinging to its rescuer.

Lastly, Warsaw’s row with Brussels about rule-of-law backsliding has plagued Polish politics for the past two years. In 2020, the EU ramped up sanctions against Poland, withholding €36 billion in COVID-19 recovery funds as well as fining Warsaw a record €1 million-per-day for failing to dismantle its controversial disciplinary chamber for judges. Tensions with Brussels remained at the forefront in the 2023 election campaign.

Which issues surfaced the most state-backed media on search engines?

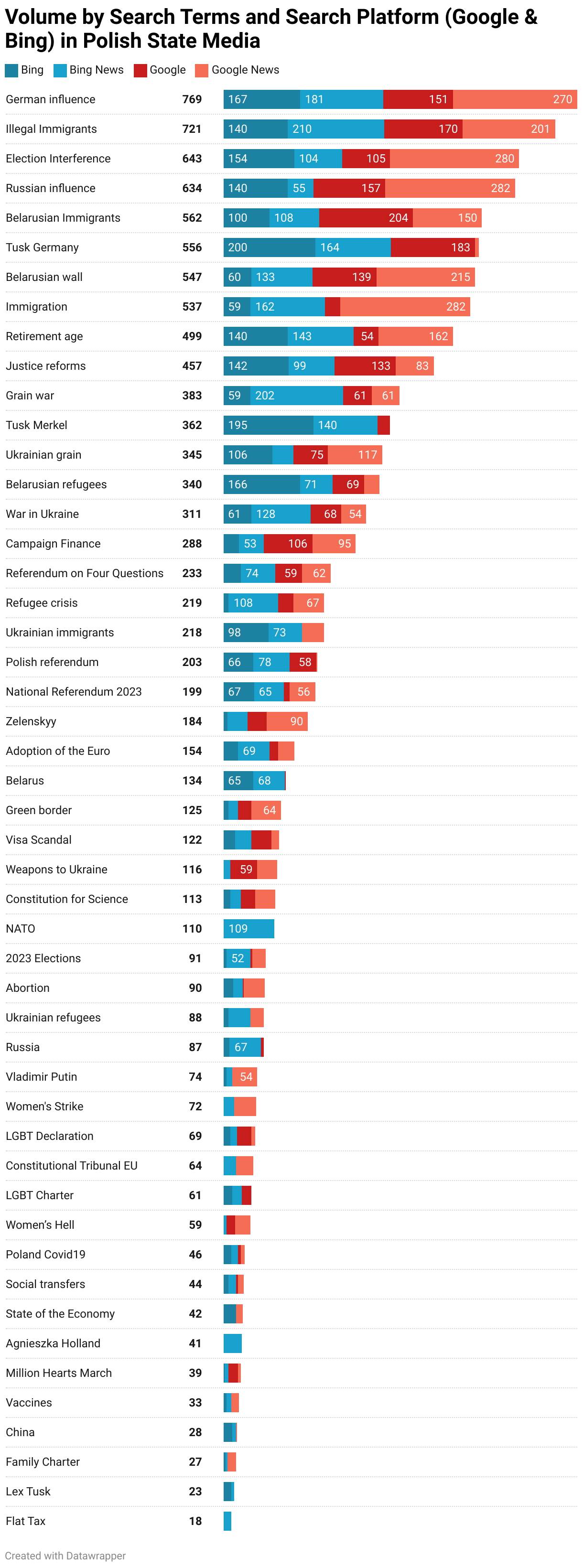

To test the issues that produced the most state-backed media returns in search results, we queried approximately 50 terms and phrases related to the key electoral topics outlined in the previous section. We found that, in our dataset, Polish state media were more likely to surface in search results on queries concerned with external influences on Poland rather than domestic social issues.

Seven of the ten search terms in our study that returned the most state-backed media were related to concerns over immigration, refugees, or external influence emanating from countries like Germany, Belarus, and Russia. The term that produced the most state-backed media occurrences—“German Influence” (wpływy niemieckie)—and the term that produced the fourth most state media results—“Russian influence” (wpływy rosyjskie)— both speak to specific apprehensions about the threat of foreign influence in Polish society that was central to PiS’s electoral messaging. Illegal immigration, particularly from Belarus, also produced a substantial amount of Polish state media returns. Specific terms linked to illegal immigration ranked second, fifth, and seventh, and the more general term “immigration” (imigracja) ranked eighth.

Queries related to PiS’s dispute with Ukraine also returned a comparatively significant amount of state media content, with “Grain war” (Wojna zbożowa) and “Ukrainian grain” (Ukraiński zboże) producing the eleventh and thirteenth most instances of state media results, respectively. Polish Press Agency (Pap.pl), a state-controlled outlet, had more than twenty unique articles appear during the studied period on searches related to the Ukrainian grain issue. This effort to keep the controversy fresh by repeatedly publishing on the issue also may have influenced search results, given that search engines prioritize “fresh” content in results.

On search engines, state-backed media had poor traction on social issues and limited success in topics related to international affairs

For economic-related search queries not related to the Ukrainian grain issue, an average of only 30 instances of Polish state media appeared per query, with most of those results not featured on the first results page. Likewise, terms associated with COVID-19 and domestic social issues, specifically LGBTQ and women’s rights, attracted a relatively low presence of state media in search results. The average number of times a state-backed media result was found for terms related to those topics were 52, 40, and 73, compared to an overall average of 127 instances of state media occurrences per search term. While it is exceedingly difficult to determine exactly why these terms generated fewer state media results, the lower visibility of state media coverage in our study suggests either an avoidance of these topics by state media or competitive displacement due to fresher content being produced by non-state-aligned media outlets.

Queries related to international affairs generated a moderate amount of state-backed media results. Notably, though, state-backed outlets became more prominent in search results when search terms were more closely linked to the aforementioned issues of external influence and refugees/immigrants. For example, search terms about the EU/Eurozone showed an average of just over 100 instances of state media coverage. In contrast, terms about the “referendum on four questions”—two “questions” of which related to immigration/border control—had nearly double that volume of returns.

Table 3. Selected Issue Sets by Average Instances of Polish State-Backed Media

|

Issue Set |

Example Terms |

Average Volume (Polish State-Backed Media) |

|

Women’s Rights |

“abortion”/”aborcja”, “Women’s Hell”/”Piekło Kobiet” |

73 |

|

LGBTQ Rights |

“LGBT Declaration”/“Deklaracja LGBT”, “Family Charter”/”Karta Rodziny” |

52 |

|

COVID-19 Issues |

“COVID-19 Polska/”Poland Covid19“, “COVID-19 Vaccines”/”COVID-19 Szczepionki“ |

40 |

|

Economic Issues |

“flat tax”/”Podatek liniowy”, “state of the economy”/“Stan gospodarki” |

30 |

|

EU/Eurozone |

“adoption of the euro”/“Przyjęcie euro”, “Constitutional Tribunal EU”/“Trybunał Konstytucyjny EU” |

109 |

|

Referendum |

“Referendum on four questions”/”Referendum na cztery pytania“, “Polish referendum”/”Polski referendum“ |

212 |

Yandex and measuring foreign influence

Instances of foreign state-controlled media within Polish search results were relatively small compared to ASD’s previous study monitoring search results in the UK. While there were 3,416 instances of Polish state media in search results, the only other notable state media presences were from Qatar—through Al-Jazeera (94 occurrences)—and Russia—via Sputnik (64 occurrences), which only surfaced on the Russian search service Yandex. The 158 total returns from foreign state-backed outlets accounted for far less than 1% of all search results in our study. The comparatively small number of returns from foreign state-backed outlets is likely due to the limited number of foreign governments that fund Polish-language media outlets, resulting in a more insular media environment. It is notable, however, that Sputnik appeared at all in search results, given the current EU ban on RT and Sputnik. Though Yandex’s market share in Poland is small (estimated at less than 1%), its seeming avoidance of EU regulatory requirements does open a path, albeit a small one, for banned content to reach Polish audiences.

Yandex search results had a similar proportion (5.5%) of Polish state media as Google and Bing, with the most state media observations clustered around much the same queries, particularly illegal immigration and refugees, that saw a significant amount of state media results on other search services. Terms related to former Polish prime minister and European Council head Donald Tusk surfaced the most Polish state-backed media results on Yandex, led by “Tusk Merkel,” which had the most occurrences of Polish state media on Yandex. The Polish state-backed articles that surfaced on Yandex tended to portray Tusk as sympathetic to or an agent of German influence.

On all monitored search services, Deutsche Welle (dw.com), an independent public broadcaster sponsored by German taxpayers, emerged as the tenth most frequently encountered domain during the studied period. Deutsche Welle featured prominently on queries related to “external influence” where Polish state media also regularly surfaced. In our study, it was the most frequently encountered domain for “Belarusian refugees” (uchodźcy z Białorusji) and the second most observed domain for “refugee crisis” (kryzys uchodźczy), “German influence” (wpływy niemieckie), and “Tusk Germany” (Tusk Niemcy).

Conclusion

This study suggests that Polish state-backed media, while present in search environments, are not as dominant in search results as they are in traditional media spaces. For example, on Google, only 5% of search results originated from state-backed sources, a stark contrast to state-controlled broadcaster TVP’s market dominance. However, it is crucial to note that the influence of Polish state-backed media was not entirely absent from search engine results. On issues like refugees, immigration, and external influences, there was a noticeable presence of state-backed media in search results. For instance, terms like “German Influence” and “Russian Influence” saw a higher incidence of state media links, with up to 30% of results from Polish state-backed media.

Search engines do not exist in a vacuum and are part of a larger media ecosystem. The presence of state-backed media in search results, albeit lower than in traditional media, highlights the ongoing challenges in ensuring a truly pluralistic and diverse media landscape in Poland. The data from this study emphasizes the need for continued vigilance and analysis to understand the dynamics of state-backed media influence in the digital age, especially during elections and other crucial times.

The authors would like to give special thanks to Marta Prochwicz-Jazowska and the GMF Warsaw office for contributing research to this report.