A Turning Point for Europe and India

In fact, the format is rarely used and offered by the EU. Such a meeting was supposed to take place last year with China’s President Xi Jinping under different circumstances but, with new tensions in the EU-Chinese partnership after the coronavirus crisis, it was reduced to a different, much smaller format. This unprecedented meeting marks a turning point for the Europe-India relationship, and the culmination of sustained efforts by New Delhi to invest more diplomatic resources in Europe, reversing years of political neglect. It also reflects a marked change of tone and posture in Brussels and other European capitals, which seem keen to invest much more effort into ties with India.

The deliverables of this meeting will likely include four major agreements—on connectivity, trade and investment, climate change, and most importantly pandemic response and recovery—in addition to a host of other issues. The agreement on infrastructure connectivity is supposed to present an EU and Indian alternative to China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), based on norms of transparency and sustainability, and focusing on transport, energy, and crucially digital infrastructure. Both sides will seek to coordinate on strategic projects in the Indo-Pacific and on EU investment in projects in India. The meeting is also likely to announce resumption of negotiations on a free-trade agreement. While these agreements are substantial, the real value of this Leaders’ Meeting lies in symbolism and signaling. For Prime Minister Narendra Modi, it is a historic opportunity to present India’s ambitions and priorities for Europe. For EU countries, which have been criticized for not taking a stand on China, it is an opportunity to show the world they take seriously their promise of “diversifying” their partnerships beyond China and to invest more diplomatic and political resources in the Indo-Pacific.

For those who complain that the EU-Indian partnership is all talk and no substance, over the last four years, but especially since the 2020 summit under the new European Commission, the scope of cooperation between the two sides has massively expanded. In the last year alone, they have met for a newly launched dialogue on maritime security, set up a working group on 5G, launched a joint Artificial Intelligence Task Force, and started a new digital investment forum. They also have restarted a human-rights dialogue after eight years and held a ministerial High-Level Political Dialogue to revive the discussions on the free-trade agreement or find ways toward an investment agreement, as well as regular foreign, security, and defense consultations. At India’s flagship Raisina Dialogue last month, NATO’s secretary general made a pitch for expanding coordination with India on common security challenges. And in recent weeks the EU and its member states were among the first to reach out with messages of solidarity and a supply of critical medicines and oxygen as India was hit by the devastating second wave of the coronavirus pandemic. The EU, which is legitimately criticized for slow response times in crisis situations, deployed its Civil Protection Mechanism to transport supplies from Belgium, Ireland, Luxembourg, Portugal, Romania, and Sweden within days. This list is growing as more European countries pitch in. Meanwhile France and Germany have launched a substantial bilateral aid effort for tackling short- and long-term implications of the pandemic in India.

What is driving Europe’s interest in India? The China factor is one explanation. In fact, European perceptions of India have been changing in tandem with increasing tensions with China. In 2018, the EU released a new strategy for cooperation with India, calling it a geopolitical pillar in a multipolar Asia, crucial for maintaining the balance of power in the region. Reinvigorating the India partnership is also a key pillar of the EU’s Indo-Pacific strategy, as well as those of countries like France, Germany, and the Netherlands (as well as the United Kingdom). Similarly, India’s response to the China challenge has focused on strengthening partnerships, economic decoupling, and diversification. This not only includes strengthening ties with its Quad partners (Australia, Japan, and the United States) and Southeast Asia but also Europe. It is no coincidence that items on the Europe-India agenda—maritime security in the Indian Ocean, alternatives to the BRI, emerging technologies, 5G, and AI—all have elements of competition with China.

But this is not the only explanation. India has been increasing its political and diplomatic investment in Europe since the mid-2000s, reviving dormant partnerships. This has not always been a linear or perfect process, but the foreign policy establishment is beginning to realize that Europe could be an important partner in building India’s domestic capacities and resilience. Several new partnerships have focused on increasing trade and investments, green partnerships and climate change, new technologies, and defense manufacturing. Similarly, Europe’s interest in India is driven not only by the Indian market but also a belated yet clear recognition of its geopolitical significance in the Indo-Pacific.

This week’s Leaders’ Meeting, however, comes in the shadow of the devastating second wave of coronavirus in India that caught the government, which was quick to declare victory against the pandemic in January, on the back foot. That European countries, like other partners, have rallied around and provided crucial medical support is a testament to and a result of India’s investment in these partnerships. It is also partly due to India’s health diplomacy last year when it supplied medical equipment and vaccines around the world. But how the government responds to and emerges from this crisis will determine the trajectory of India’s domestic and foreign policy more than anything else. If it does not come up with a plan to tackle the short- and long-term effects of the pandemic on India’s health and economy, this will not only impact India’s capabilities but also fuel the global crisis. For Europe, this moment should be a wake-up call that the crisis is not over with vaccines for European citizens. It urgently needs to work on equitable vaccine production and distribution with partners like India.

Europe-India Ties in Eight Charts

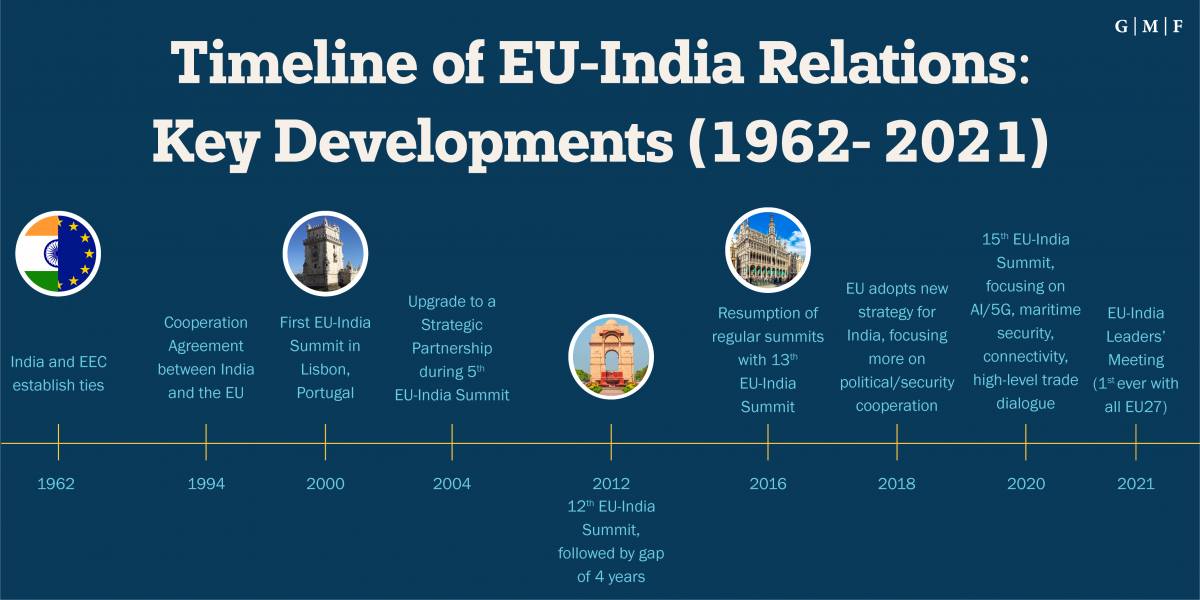

The history of EU-Indian relations has gone through waves and troughs—high points marked by signing of political agreements, even higher expectations, which were then not followed through often as both sides got distracted by other priorities. The Cold War division of Eastern and Western Europe—still reflected in the organization of India’s Ministry of External Affairs’ into divisions for Europe West, Central Europe, and Eurasia— made it difficult for New Delhi to develop a nuanced picture of modern Europe. Furthermore, bureaucratization of engagement, especially with Brussels, meant the relationship stagnated due to lack of political will on both sides.

A noticeable shift in this trend is visible from mid-2000s, as India increased its outreach to Paris, London, and Berlin while also spending more time on the relationship with Brussels and Europe’s sub-regions. Senior political visits to Europe increased substantially—in many cases marking the first time an Indian prime minister had visited the country in decades, included the first summit with Nordic countries and a revival of ties with Portugal and Spain. Summit-level meetings became more frequent, especially focusing on previously under-explored or unexplored partnerships—for instance, with Finland.

Another element of India’s outreach has been to revive ties with Central and Eastern Europe. In 2019, India’s foreign minister visited Bulgaria and Serbia, its president traveled to Slovenia, and its vice president undertook the first high-level government visits to Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania, laying the foundation for political dialogue and outreach. Since the 2000s, there has also been a significant increase in Indian companies investing in Central and Eastern Europe in green and brownfield investments and in industries like IT, business process outsourcing, and financial services.

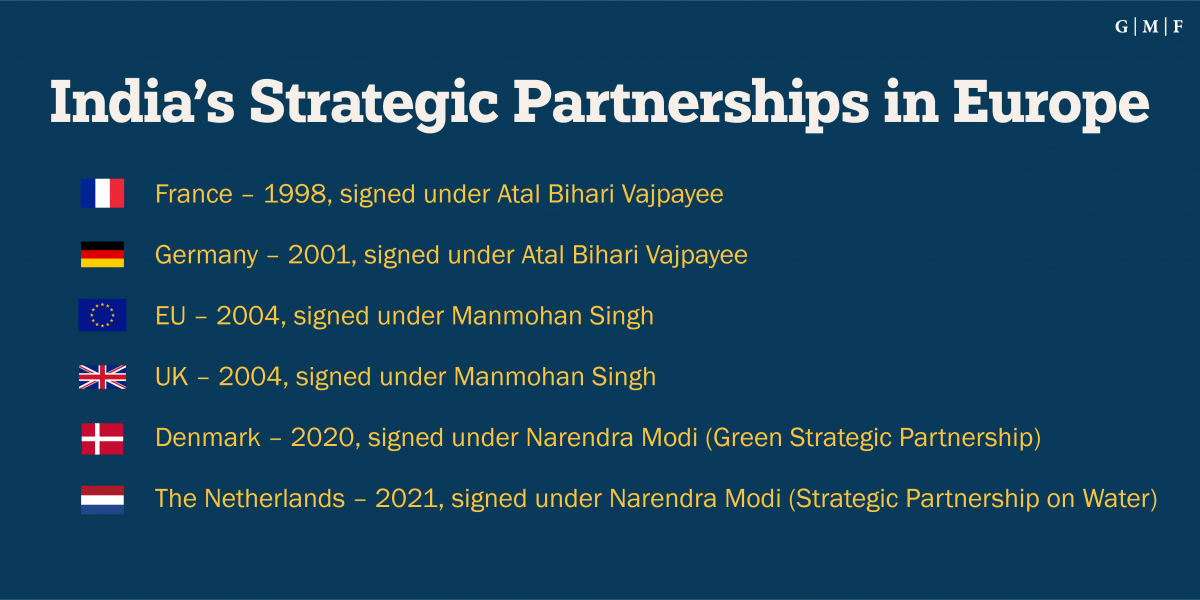

India now has six strategic partnerships in Europe, including a Green Strategic Partnership with Denmark that focuses on green and climate-friendly technologies, implementing the Paris Agreement, and meeting India’s climate goals. Its strategic partnership with France is arguably the strongest and has delivered the most.

India is beginning to realize partnerships with the EU can be useful for building domestic resilience and capacities, which is needed for its domestic and foreign policy objectives. Similarly, the EU is also keen to be a part of the India growth story and to diversify its economic partnerships beyond China. Free-trade negotiations have been a sticking point so far though, as noted above, the Leaders’ Meeting could see the announcement of a resumption of negotiations or movements toward a phased agreement. Even without the agreement, however, the economic partnership has flourished. The EU as a bloc is India’s largest trading partner and the second-largest destination for Indian exports. After deciding to not join the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership, Indian officials seem keen on reviving a deal with the EU. However, given India’s traditional reluctance towards free-trade agreements, some recommend focusing on areas such as investment “where it is still possible to immediately find points of consensus.”

For a long time, India’s European partnerships were defined by economic cooperation, but as trade, technology, and climate change all have taken security implications, ties have begun to focus on security and defense as well.

France is not only one of India’s most important security and defense partners in Europe, but also globally. As Europe pivots to the Indo-Pacific, security cooperation is also set to grow with other countries and the EU.

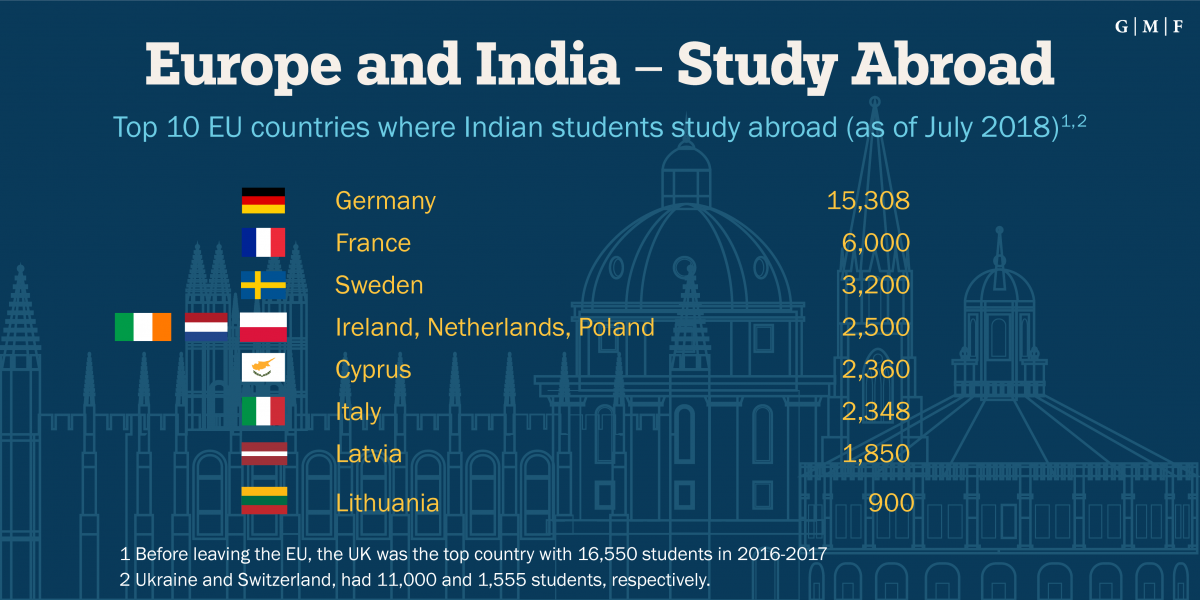

Europe also continues to be the preferred destination for Indian students.

The author would like to thank Franziska Luettge and Kirsten Langlois for their contribution to the research for this paper.