How the Greens and Liberals Could Breathe New Life into German Politics

Editor's Note: This text was updated slightly on October 7 to include the official negotiation decision.

For decades Greens and Liberals were seen as the most unlikely partners to team up in a coalition on the federal level in Germany. Now the shape of the next government is in their hands. Together these traditionally smaller parties received the largest vote share in the recent parliamentary elections, making it all but certain that they will be part of the next governing coalition. The only way the Social Democrats (SPD), who narrowly came first, or the Christian Democrats, who came second, would be able to form a government without them would be to partner up in yet another grand coalition. But this option is very unpopular among the public and the two larger parties, making it highly unlikely.

Thus, Germany now looks at the novel experience of the two smaller parties in any likely governing coalition trying to hammer out a joint position that they will put to their larger potential partner, beginning with the SPD, who was announced on October 6 as being the chosen party to officially negotiate with. As an alternative coalition with the conservatives remains an option, the Greens and Liberals have an opportunity to exert policy influence within the next government greater than ever before and could breathe new life in German politics.

But the dividing lines between the Greens and the FDP run deep, and not only where it comes to taxation, debt, and state insurance. They have fundamental philosophical differences, including on the role the state should play in society. While the Greens tend to believe in the guiding hand of the state, the FDP has a deep suspicion of guidance coming from politicians and bureaucrats. In an economic sense the fight is between the schools of John Maynard Keynes and Friedrich Hayek—about the state versus the market.

Much more is involved in their negotiations than tax brackets, caps for rents in real estate, or boosting e-mobility. It is about reconciling almost adversarial approaches. If the two parties find ways to bridge a gap that some observers compare to the Grand Canyon, the result could be more than just another coalition platform hammered out in nightly sessions.

The key for success might be found in the demographics that helped the Greens and the FDP to their good election showings of 14.8 percent and 11.5 percent respectively. Both enjoy the support of young voters: the FDP led among first-time voters, the Greens among voters between the ages of 18 and 24. The SPD, which came first overall and is their most likely coalition partner, has a much different base and scores particularly well among pensioners and workers.

Having the support of the youth vote is a blessing and a curse, however. Attracting the younger generations early on may secure a stable voter base for these two parties in the future. But young voters who are very much driven by the topics of climate change, digitization, education, and individual freedoms impatiently want the parties to deliver. Any compromise on some of these issues could cost them this youth support.

There are commonalities between the Greens and the FDP, although in the public eye these are often buried under the differences. For example, both want to liberalize drug use, to lower the voting age to 16 years, and to do away with the section of the criminal code that punishes those who advertise abortion services. Both believe that Germany lags behind in its digital infrastructure and has not paid enough attention to its education system, especially during the pandemic.

Unbridgeable Differences on Taxes and Debt?

While these topics are relatively easy to agree on, it gets more complicated on climate, taxes and debt. The Greens want to shorten the timeline for exiting coal power and ending the production of combustion engines. While the FDP is opposed to rushing things, it agrees with the Greens about the ultimate goal of a significant reduction of CO2 emissions. A newly tailored system of emissions trading, which has been floated in public debates, could serve as a silver bullet. By markedly raising prices for CO2 certificates, this would push companies to adjust much faster. However, the trading system is a market tool rather than state interference, leaving companies to decide how to come to terms with the new conditions, suggesting it may be more acceptable to the FDP than to the Greens.

On taxes and debt, the two parties are far apart and will be under pressure to deliver on their campaign promises. While the Greens want to lift the debt ceiling, introduce a wealth tax, lower taxes for medium incomes, and raise taxes on higher incomes, all of which the FDP opposes. Exemptions could be a way to bridge these incompatible positions. For example, the Greens could agree that debt will not rise in general as long as there is an exception for state investments related to the fight against climate change. Although this would not reflect pure party thinking on either side, it could be an acceptable compromise for each one. This approach would be conceivable also in other areas as a way to bridge over their fundamental differences.

A Clear Stand against Authoritarianism

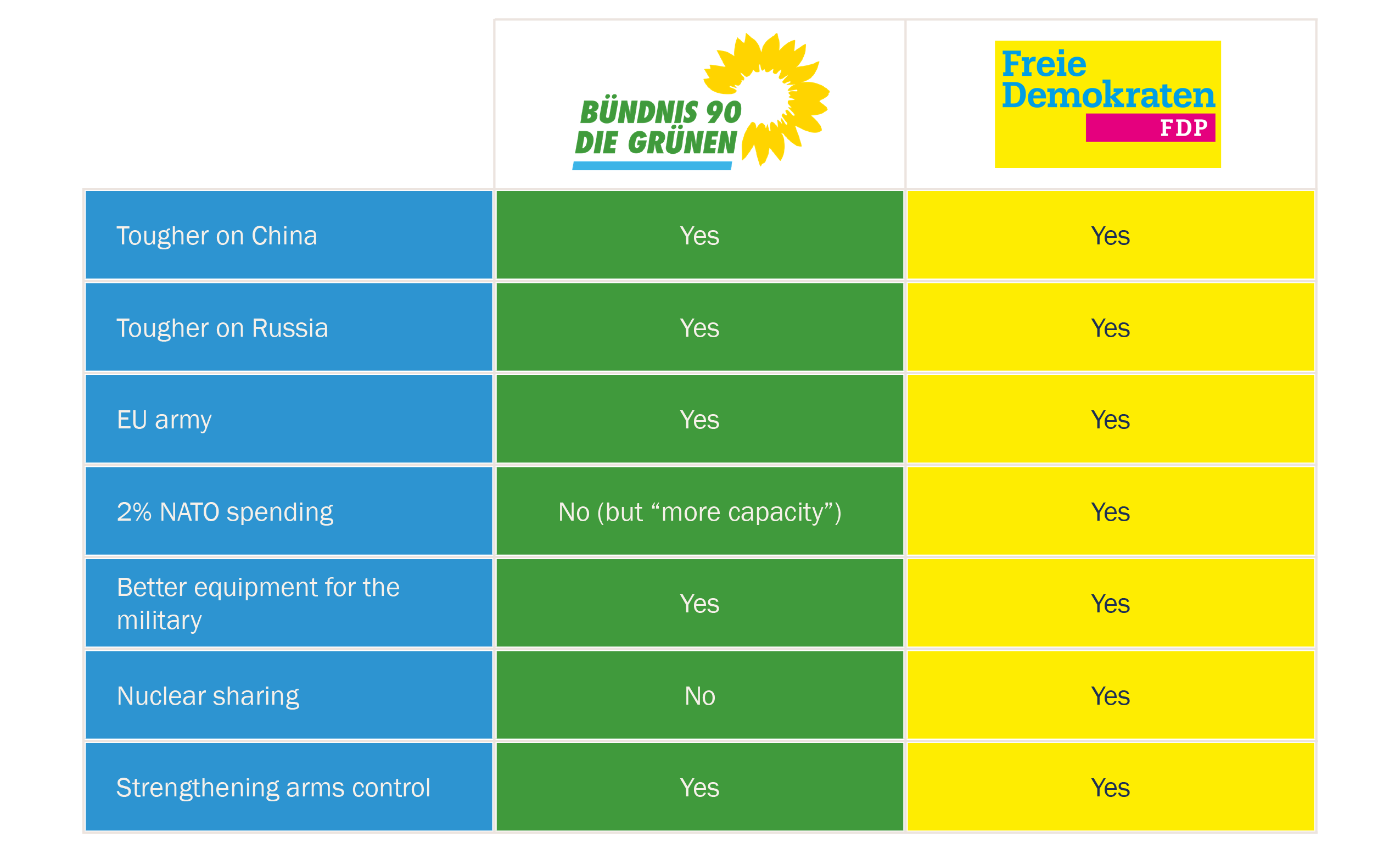

On foreign affairs, the FDP and the Greens have common ground on some key questions—most importantly in their more holistic approach to foreign, security, and development policy, and their emphasis on human rights and the human dimensions of security. Both parties are highly critical of authoritarian regimes. Their goal of defending human rights globally aligns well with the United States’ priorities of countering strategic rivals like China and Russia. The FDP even endorsed President Joe Biden’s emphasis on democratic multilateralism in its electoral program and envisions Germany as a key contributor. Meanwhile the Greens have called for putting an end to the Nord Stream 2 pipeline—although the window of opportunity to halt the project has likely closed following the deal between the Biden administration and the outgoing government.

The liberals cast themselves as committed transatlanticists and unequivocal NATO supporters. They want to strengthen rules-based multilateralism and advocate the creation of a National Security Council to facilitate a unified foreign, security, and development policy as well as faster and more sustainable decision making. Traditionally, the Greens have been more skeptical of conventional defense and deterrence efforts. They are more comfortable casting security through the lens of peace building. At the same time, they stress that Germany has to take more responsibility in the world and in Europe. All this bodes well for the future of transatlantic relations.

Reacting to Threats Facing Germany

The FDP and the Greens have highlighted the importance of adequate equipment for Germany’s military—an issue that has been a source of international criticism and ridicule in recent years. The liberals believe that funding is key for the modernization of the armed forces and supports Germany’s commitment to the 2 percent of GDP defense-spending target for NATO. Meanwhile, the Greens’ electoral program foreshadowed some potential complications. The party rejects a numerical spending target and wants to place greater importance on outputs and capabilities instead. Although this argument is not new in NATO circles and has some support, any spending that falls short of the 2 percent target would likely exacerbate doubts about German reliability across the alliance.

This could be a cause of friction with Germany’s allies, especially in case of a coalition led by the SPD, which until recently had been highly critical of the NATO spending target. Although the SPD did not explicitly address the 2 percent question in its electoral program and its chancellor candidate, Olaf Scholz, has emphasized that defense spending grew during his time as finance minister, it is not clear how much support there is for higher spending in the party’s base.

Nuclear weapons could be another potential sticking point and could put Germany on a collision course with the United States and other NATO allies. The Greens reject Germany’s participation in NATO’s nuclear-sharing agreement and questions the alliance’s deterrence posture. Their program called for NATO to renounce its first-strike policy, though the fact that there is no clear timeline tied to these demands suggests flexibility.

In an SPD-Greens-FDP coalition, the nuclear question could become a real issue as Germany faces a decision about the replacement of its obsolete nuclear-capable fighter-jet fleet. If the next parliament fails to approve the procurement of a suitable successor model, Germany will effectively be unable to deliver on its nuclear-sharing commitment beyond 2030 when the old model will be phased out.

However, in the end realism may prevail—especially for three parties eager to prove they can govern together and that have signaled their readiness for compromise. Although the Greens originate from the anti-nuclear movement, today’s party has little resemblance to that of the early 1990s. The party’s record of supporting military missions from Kosovo to Afghanistan despite its anti-war ideology and the pushback from its base has demonstrated its willingness to compromise over time.

Against the backdrop of transatlantic relations that continue to be shaken by disagreements and perceptions of U.S. unilateralism, discussions around greater European strategic autonomy will likely continue. The FDP and the Greens want to strengthen the European Union and buttress its credibility and clout in foreign and security policy. The FDP even supports the creation of a European army with headquarters in Brussels. These views will likely be welcomed by France’s President Emmanuel Macron, who will run for reelection next year. But a balanced approach toward Germany’s two most important allies remains key.

To achieve that, the FDP and the Greens will have to put compromise first—not just among themselves but also with the SPD (or even potentially with the Christian Democrats) as their other potential coalition partner. If these two parties are able to bridge their fundamental differences on questions relating to the state and the market, this could also be a viable path forward in negotiations with the SPD and a unique opportunity to forge a broad alliance across society. The good news is that, after the failed coalition talks of which they were part in 2017, the Greens and the FDP seem to grasp the importance of their responsibility.