Securing Our Health

Just days after taking office, Japan’s new prime minister, Sanae Takaichi, made clear that health security will be a priority for her government. 1 She emphasized in a policy speech that “protecting the lives and health of the people is a critical component of national security”. She also underscored the importance to Japan’s health security strategy of comprehensive preparedness for the next infectious disease crisis and of robust measures against chemical, biological, radiological, nuclear, and explosives (CBRNE) terrorism.

In noting this, Takaichi may be reflecting on a lesson learned from the COVID-19 pandemic: that the threat of bioterrorism and naturally occurring pandemics highlights the need for resilient response systems that transcend the boundaries of the civilian, public health, and military sectors. Strengthening health security among them, therefore, is no longer a choice. It is a strategic necessity, especially as geopolitical tensions rise, natural disasters become more frequent and complex, and emerging technologies such as artificial intelligence (AI) and gene editing rapidly evolve.

Building Resilience

The COVID-19 pandemic exposed critical challenges in international public health governance and underscored the need for national whole-of-government responses. Public health agencies played a central role in disease surveillance and containment, but limits to their logistical capacity and inter-agency coordination, often hindered by siloed structures, became apparent during large-scale operations.

In contrast, military institutions demonstrated their value through rapid deployment capabilities and logistical expertise. US armed forces, for example, supported vaccine distribution and mobilized resources by establishing and overseeing temporary medical facilities that supported overwhelmed health systems. Japan’s Self-Defense Forces managed logistics for mass vaccination centers while French military medical units were dispatched to support inundated civilian hospitals. These cases illustrate that military support can prove instrumental when a health crisis overtaxes public health and civilian institutions.

Countries in the Indo-Pacific and in the Atlantic community are advancing health security by drawing on lessons from their COVID-19 experience. But their approaches differ. In the Indo-Pacific, countries are emphasizing institutional development and public health capacity-building, often by creating new agencies and mechanisms focused on infectious disease control and disaster response. Japan, Singapore, and Australia have launched new government bodies to do this, and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) has set up the ASEAN Centre for Public Health Emergencies and Emerging Diseases (ACPHEED) to enhance regional coordination. Countries in the Atlantic community, in contrast, have integrated health security into existing institutional frameworks. NATO, for its part, has incorporated a health dimension into its framework for national resilience, encouraging member states to strengthen civil support systems in times of crisis. And the EU has established the Health Emergency Preparedness and Response Authority (HERA) as a new directorate-general within the European Commission, building on existing mechanisms to coordinate medical countermeasures (MCMs) and crisis response. HERA is a public health directorate, not a military unit, but it emphasizes the importance of civil-military collaboration in MCM research, development, and deployment.

Creeping Contagion

Public health systems are generally well equipped to respond to naturally occurring outbreaks, but they often face limitations when dealing with intentional biological threats such as bioterrorism or state-sponsored biological weapons. The challenges in this regard are only growing.

Rapid advancements in biotechnology complicate the ability to assess threats. Technologies such as synthetic biology and AI-enabled pathogen design that possess dual-use characteristics heighten concerns about possible engineered pandemics. And complex crises, such as the convergence of infectious disease outbreaks with natural disasters, or outbreaks linked to international mass gatherings, demand planning and responses that exceed the capacities of traditional public health frameworks.

Three plausible scenarios illustrate the challenges that can rapidly arise and demand an international and multi-sector response:

Scenario 1: Deliberately Engineered Pathogen (Actor Unspecified)

A pathogen with high transmissibility, pathogenicity, and immune evasion is deliberately engineered with AI and emerging technologies, and released into a metropolitan area. The actor could be a state or non-state entity. The ambiguity demands cooperation nationwide and across many societal sectors to contain the pathogen.

Scenario 2: Compound Crisis of a Natural Disaster and an Infectious Disease Outbreak

A major earthquake strikes a remote area, destroying infrastructure and disrupting sanitation. This leads to simultaneous outbreaks of norovirus, influenza, COVID-19, measles, rubella, and food-borne illnesses. Standard transportation routes are disrupted, making the delivery of supplies and personnel difficult. Again, this double blow demands cooperation nationwide and across many societal sectors to tackle the coincident crises.

Scenario 3: Global Outbreak Triggered by an International Mass-Gathering Event

A novel respiratory virus spreads among players and spectators during a major international sports event. It crosses borders quickly, exposing the limitations of national response systems and the challenges of multinational coordination. Global collaboration is needed if the spread has any chance of being controlled.

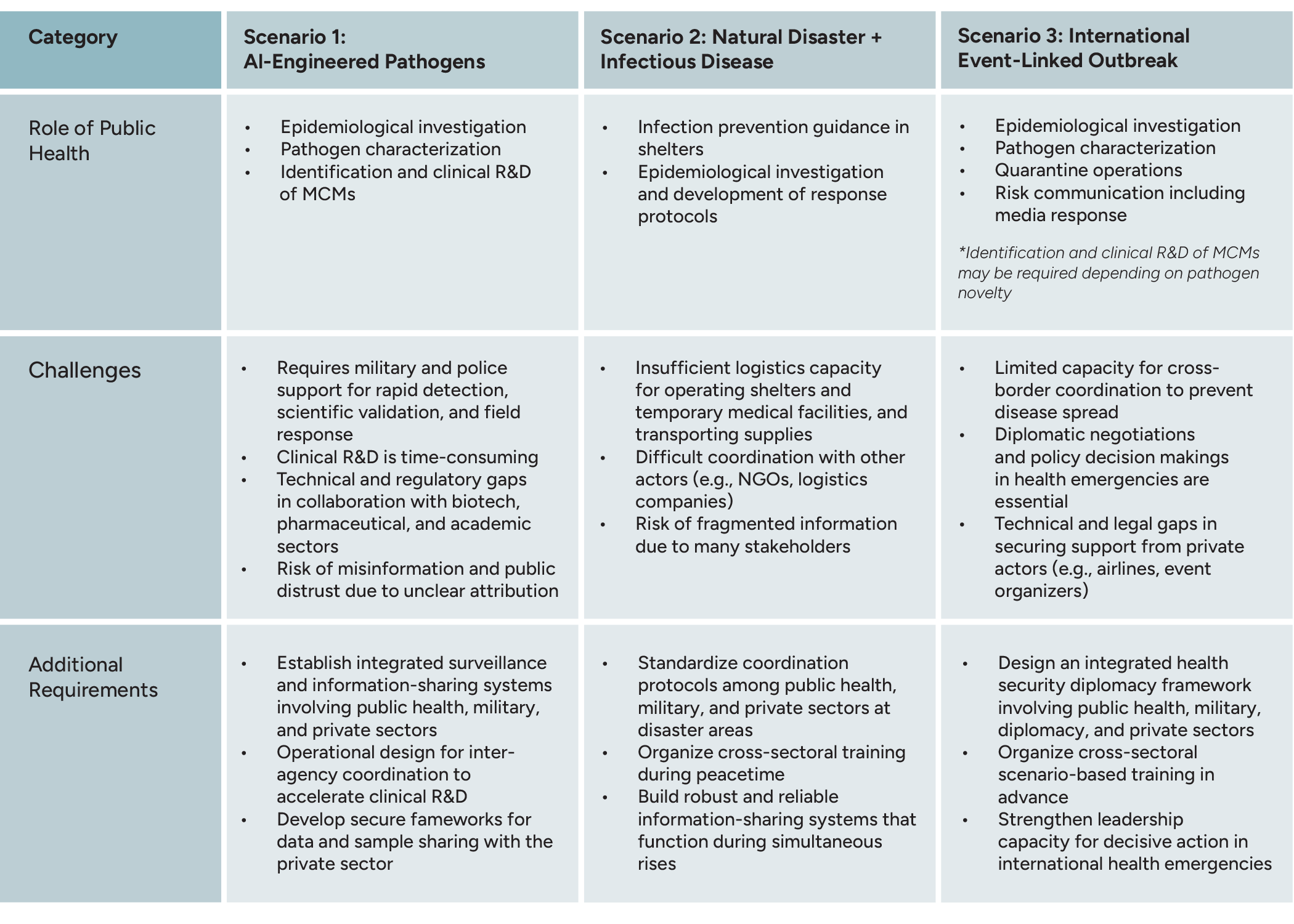

The table below sets out in more detail the factors that may constrain public health systems in responding to credible health crises that can emerge with little or no warning.

It Takes More Than a Village

COVID-19 exposed challenges in global health systems and underscored the need for integrated responses. The situation has become only more acute since then as biological threats grow more complex, natural disasters become more frequent, and international interactions intensify. All these developments demand that health security also evolve. But collaboration among the public health sector, the military, and the private sector must transcend tactical coordination. It must be a strategic imperative that includes establishing secure and resilient systems for sharing information, data, and biological samples. Equally important is the design of international health security frameworks that include diplomatic actors. Only by cultivating such cross-sectoral participation will effective collaboration to establish joint command structures and rapid and appropriate decision-making in health emergencies be possible.

Efforts in the Indo-Pacific and Atlantic regions reflect distinct geopolitical contexts and institutional frameworks, yet both aim to strengthen health security. This common commitment deserves attention. Recognizing that health security is national security, nations must respond with greater resolve in an era of uncertainty. And they must do so together, as infectious diseases, whose impacts can quickly escalate into diplomatic challenges, are inherently transnational. To reinforce international health security frameworks, mechanisms for cooperation that transcend borders must be in place. Health security cannot be achieved individually, whether by nation or region.

The views expressed herein are those solely of the author(s). GMF as an institution does not take positions.

- 1

Health security refers to the collective measures, policies, and systems designed to protect populations from health threats that can destabilize societies and economies. These include infectious disease outbreaks, bioterrorism, and other health hazards.