It is Time to Reform Critical Social Protection Policies in the U.S. and the EU

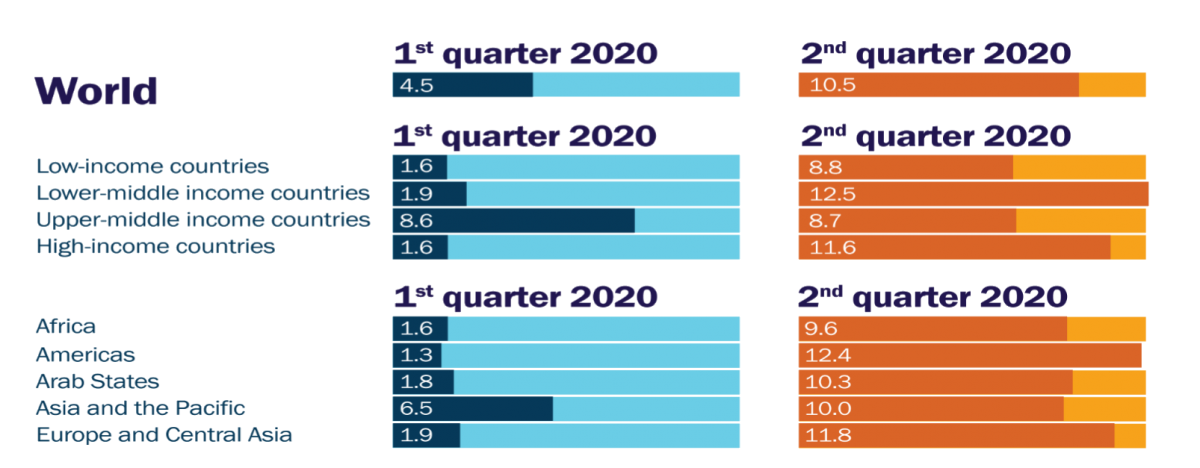

The numbers in the United States and in Europe are staggering. [1] As of April 2020, the unemployment rate in the United States rose to 14.7 percent and in Europe to 6.2 percent.[2] While high, these numbers do not capture everyone, such as those not actively looking for work. If this and other groups excluded from the count were included, the number unemployed in the United States in April would be closer to 23.5 percent unemployed.[3] Although the current unemployment rate is lower in Europe than in the United States, it is estimated that unemployment in Europe could nearly double in the coming months, with up to 59 million jobs at risk from permanent cutbacks and reductions in pay and in hours worked because of the coronavirus pandemic as Figure 1 shows. But it is those in non-standard employment relationships, i.e., workers in temporary, part-time positions and other forms of subcontracted work, as well as those in the gig economy (who are almost always classified as self-employed) whose jobs are shed first. Because these workers are not in formal employment relationships, they are most likely not eligible and therefore do not have recourse to adequate social protection, putting them at risk when they are unable to work and thus have an income. [4]

The coronavirus crisis has managed to lay bare many structural problems in societies the world over, but chief among them is the degree to which high income countries with high (or rising) economic inequality and weak (or weakened) social protection systems struggle to meet human need in the best of times, but especially now. The effect of these longstanding inequalities is evident in the United States in the disproportionately high numbers of Black people, people of color, and Native Americans infected and killed by the coronavirus. This reflects the inequalities in resources, access to care, and job quality.

The resilience of any one country to pull through this crisis is based on a number of factors which include strong public health, healthcare, and social protection systems. But key reforms made to tighten social protection systems and liberalize labor protection legislation (especially in Europe) in the 1990s in order to jump start economic growth and reduce unemployment have left individuals, especially those in non-standard employment relationships and/or working low-wage jobs, struggling to access essential cash benefits and services both prior to and especially now during the coronavirus. To build a more resilient and just society, policymakers in the United States and in Europe need to address the adverse effect these reforms have had on our ability to adequately manage old and new social risks in an ever-changing labor market. In this edition, I will briefly discuss the causes for reform and propose what is needed to change course, with a focus on unemployment compensation.

Figure 1. Estimated Drop in Aggregate Working Hours, Globally, by Region and by Income Group

Estimated percentage drop in aggregate working hours compared to the pre-crisis baseline

(4th quarter 2019, seasonally adjusted)

Source: ILO nowcasting model

Changing Labor Markets, Changing Employment Status

This rise in non-standard employment in the United States and in Europe has its roots in measures adopted to counter high unemployment in the 1970s and the 1980s. Such measures included financialization, deregulation, and new modes of corporate management. This, in addition to tightening social protection in order to ‘activate’ the unemployed into the labor market, together with the introduction of flexibilization in Europe as a way to accommodate labor processes to fluctuations in market conditions, were perceived as essential to economic growth. While the evidence is mixed as to whether flexibilization did increased labor market participation and thus reduce unemployment, the empirical evidence does suggest that flexibilization did give rise to underemployment and precarious forms of work.[5] Underemployment—defined as involuntary part-time work, self-employment, or zero-hours contract work—may suit some workers depending on their lifestyle and living arrangements. And yet, for others this type of employment represents the only alternative to unemployment, and as a result, individuals are partially excluded from the labor market.[6] Moreover, Guy Standing has written about the rise of a group of workers—identified as the precariat—that emerged within post-industrial labor markets.[7] This group has restricted skills and opportunities and declining rights. They typically experience a disproportionately high succession of low paid short-term jobs at the labor market periphery, interspersed with spells of unemployment, and who are therefore vulnerable to entrapment in a “low pay/no pay cycle.”[8]

Adapting to New Conditions

As noted, employment is no longer a binary activity—rather for many, employment consists of a portfolio of jobs.[9] It is then a question of how we define who is employed versus who is not employed, which in turn establishes who is eligible for social protection benefits when the need arises. National employment targets in the United States and the EU, as Andrea Brandolini and Eliana Viviano have argued, need to reflect the fact that people are working multiple jobs and therefore, they cannot easily be labeled as ‘employed’ or ‘unemployed.’[10] Bradolini and Viviano, among others, have called for work intensity to be measured based on the number of months worked within a year of employment and the hours worked per month. This means counting as partially unemployed people who have lost paid work that is only part of their job portfolio.

Why does this matter? If we count as partially unemployed people who have lost paid work that is a part of their job portfolio, that means our social protection systems—particularly social insurance—need to adapt and reflect these changes in employment status so that individuals can be covered during periods of partial as well as full unemployment. Social protection systems were designed to reduce inequality—in fact, it is the primary mechanisms through which societies seek to ensure a minimum level of resources for all members. Social insurance, social assistance, and basic income (i.e., a child benefit for example) are the classic components of social protection systems and the way in which income is redistributed across the life course and classic (unemployment, ill health/disability, and old age) and new (parental leave) social risks are managed. It is also important to remember that in the short-term—such as in this time of the coronavirus—unemployment compensation serves as an important antirecessionary policy given that it acts as a fiscal stimulus.

But social insurance was designed on the basis of the standard employment relationship: individuals (historically men) holding one, full-time job with a formal employment contract that contributed to social insurance. Instead of adapting social insurance to meet the changing nature of work, many European countries and the United States have made sweeping changes to social protection policies focusing on reducing coverage, length and the cash amount received, increasing the degree of income testing (to determine eligibility), and an over-reliance on flat-rate cash benefits. This in addition to attaching conditionality and stringent work and job search stipulations for those in receipt of social assistance (and increasingly social insurance too). The objective of these reforms was to move those perceived as ‘passive’ recipients of welfare into the labor market. But in the effort to ‘activate’ the ‘passive’ unemployed, policymakers failed to address the kind of labor market people were being pushed into. A job, as has been well documented, no longer necessarily provides the income security needed to cover even basic needs.

Especially in the United States, but in many European countries, too, the coronavirus has made clear that it is time to reverse reforms made in the 1990s and 2000s that were predicated on a passive/active discourse. But this varies from country to country, according to their institutional structure and specific circumstances, making comparisons or suggested changes difficult. The following will therefore provide high-level recommendations for needed changes to social protection systems, with a focus on unemployment compensation only. These high-level suggestions resonate in both the United States and in Europe. Central to any recommendations is the need to return to the original foundation of the insurance principle as a social “right” thereby rejecting income-tested, flat-rate cash benefits as the main determinant of social protection. Returning to the foundation of the insurance principle means raising the amount of cash benefits, extending coverage and length to address changing social risks and new forms of labor.

Extend Benefit Coverage

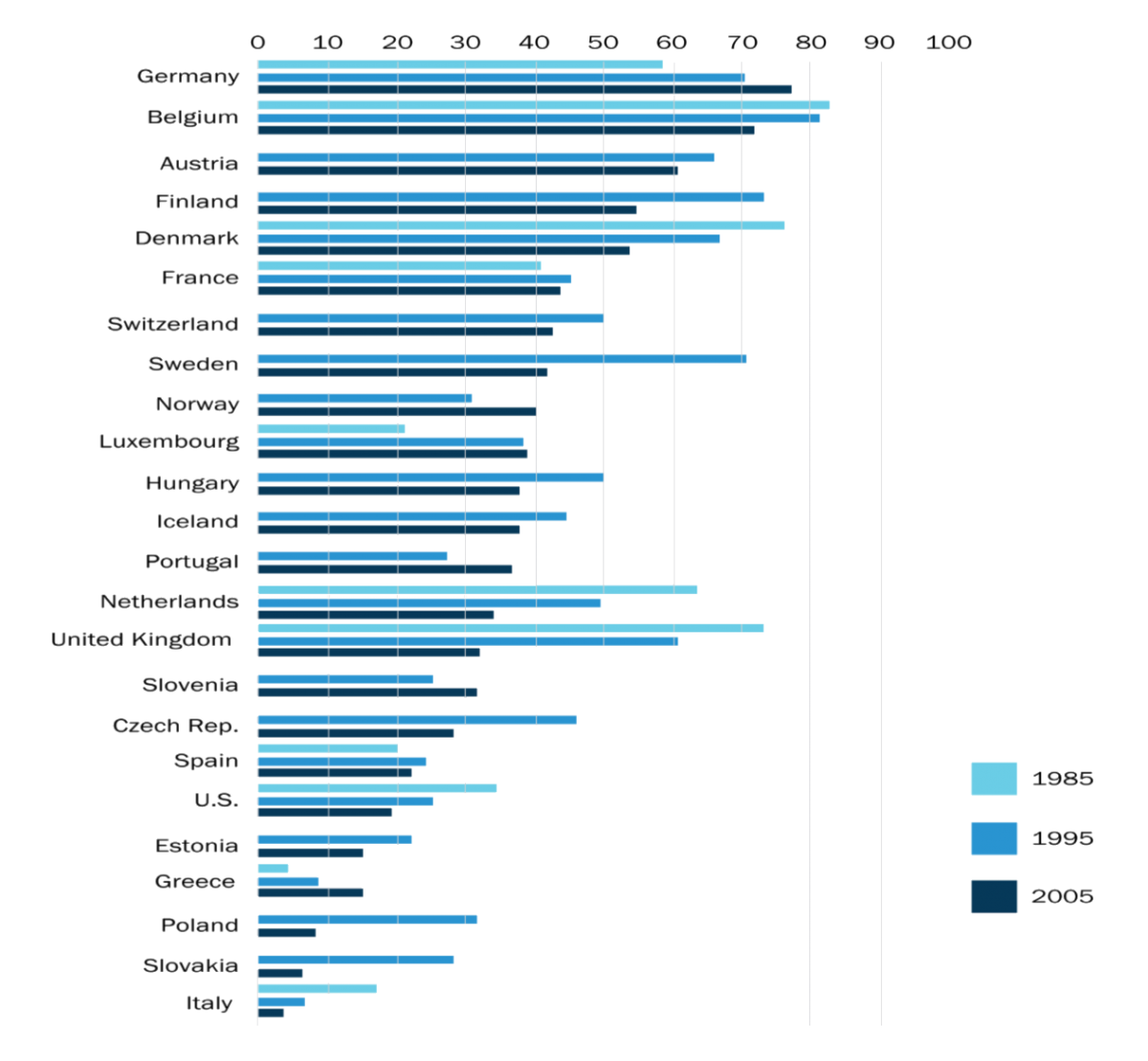

Ensure that coverage is extended to short-term, part-time, self-employed, and other nonstandard workers. According to the ILO definition, coverage is defined as the proportion of those who are classified as unemployed who receive benefits (including unemployment assistance as well as unemployment insurance). In some countries coverage has increased. But, as Figure 2 illustrates, in the majority of countries, coverage fell between 1995 and 2005. In 2005, coverage was below 50 percent in all 24 OECD countries apart from Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, and Germany. In ten of the 24 OECD countries, coverage was less than one-third.[11] In the United States the percentage of all jobless workers receiving unemployment insurance dropped from 43.7 percent in 2001 to just 27.8 percent in 2018, with low-wage workers the least likely to receive benefits.[12]

Figure 2. Percentage of Unemployed Receiving Benefit

Source Atkinson, Inequality, 2015.

The fact that many unemployed people do not have recourse to and therefore do not receive unemployment compensation comes as a surprise to many. The EU has been at the fore in developing employment rights for part-time and other nonstandard workers, but as noted, unemployment compensation systems need to ensure that these are fully matched in any reformed social insurance system. Part-time unemployment is covered in Austria, Germany, Ireland, and Portugal. In Finland, jobseekers have been entitled to an adjusted unemployment allowance if they have income from a small business activity that does not prevent them from accepting other work and where they are in part-time work through no choice of their own—but this should be extended if it is one’s choice as well.

Moreover, while social insurance is designed to manage class social risks, there are new social risks, such as caregiving, that need to be adequately covered too. For example, the United States desperately needs a national parental leave cash benefit. In both the United States and Europe, pensions should be paid for years when people have caregiving responsibilities that qualify them for credited contributions. Paid work—be it through the gig economy or otherwise—and caregiving responsibilities need to be viewed through policymaking as of equal value and as such contributing to society.

Extend Benefit Generosity and Length

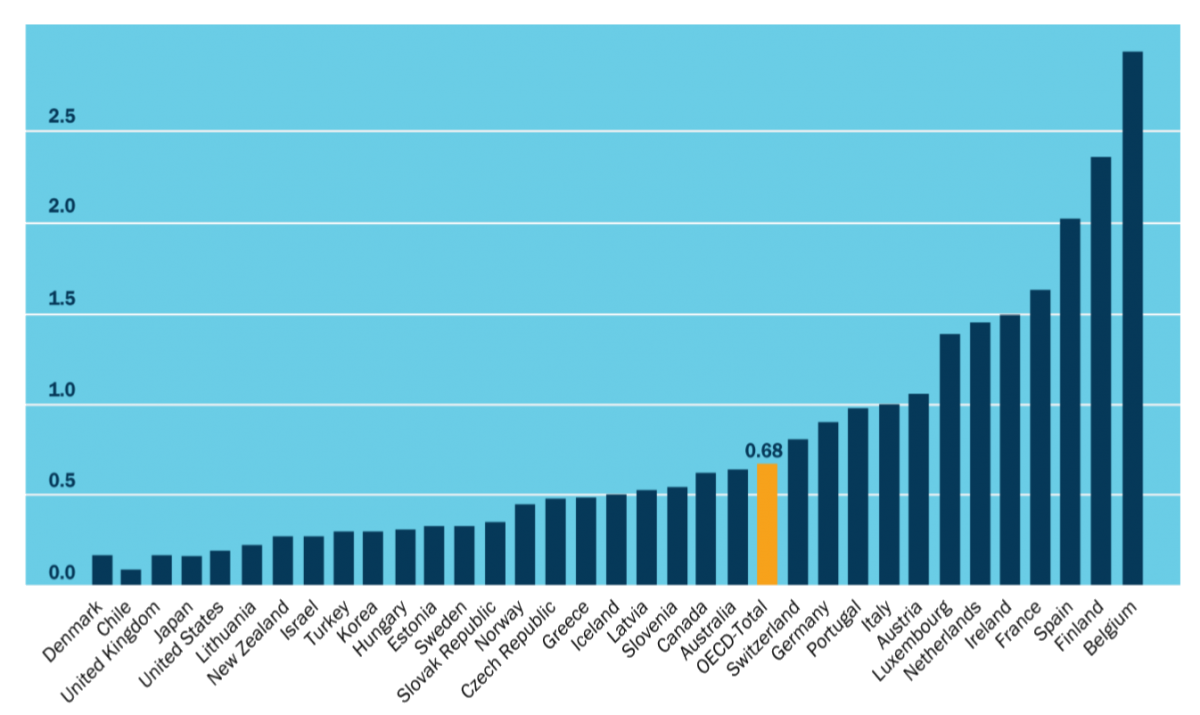

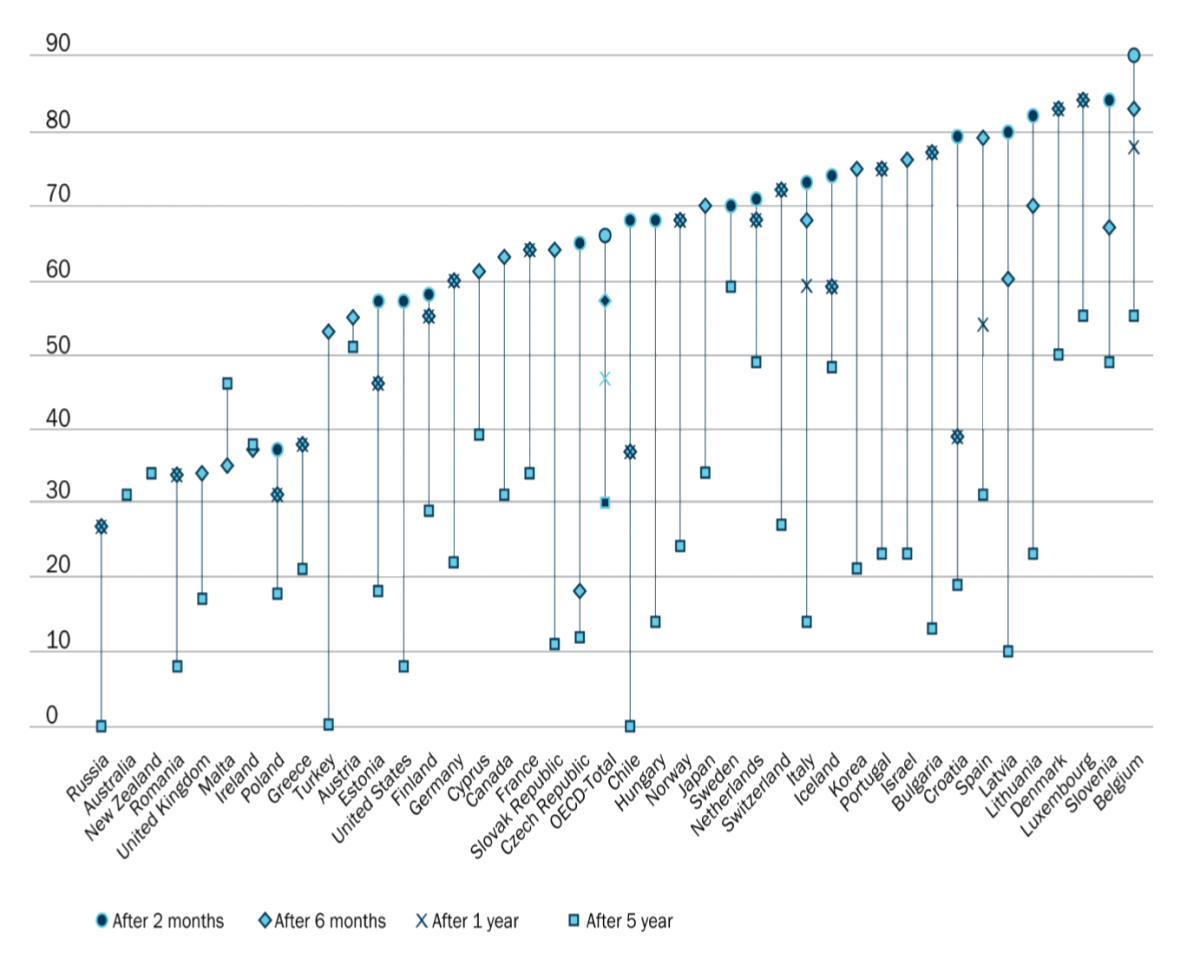

In the United States, unemployment insurance has been underfunded for decades. In fact, as seen in Figure 3, the U.S. spends less than most OECD countries on unemployment compensation. Cash benefits averaged a weekly benefit of $382, representing only 32.7 percent of the average wage. In Europe, the wage replacement rate varies from country to country, with Finland, France, Estonia, and Latvia averaging 40 to 50 percent of net earnings and Germany, Spain, and Italy averaging 60 to 75 percent of net earnings as Figure 4 shows.[13] To harmonize the various unemployment benefit systems, calls have been made for an EMU Insurance Scheme that would extend coverage to all employees in the European Union, including part-time workers and the self-employed, with an average replacement payment of 50 percent of the insured wage (or 33 percent of average earnings in the country) and where unemployment benefits are paid for 12 months. While the cash amount is still small, it would act as a foundation upon which national governments would be encouraged to top up the payments from the European level and extend its coverage to other unemployed groups.[14]

Figure 3. Public Unemployment Spending

Total % of GDP, 2017 or latest available

Source: Social Expenditure: Aggregated data, OECD

Figure 4. Benefits in Unemployment, Share of Previous Income

After 2 months, six months, one year and five years, % of previous in-work income, 2019 or latest available

Source: Benefits and wages. Net replacement rates in unemployment, OECD

In the United States minimum state standards around benefit length and generosity need to be established through federal law. Receipt of benefit should be extended to 12 months. Benefit generosity should be extended to a replacement rate of 60 percent of a worker’s weekly wages (67 percent for a worker with dependents). As it currently stands, each state runs its own unemployment insurance (UI) program and thus has latitude to set the length and generosity benefit. While the U.S. Department of Labor oversees the system and pays for the administrative costs, the states provide most of the funding and pay for the actual benefits provided to workers. Because of this arrangement, there is wide latitude from state-to-state between length of benefit and average weekly payments. The national average is roughly $378 per week, but cash benefits range from as low as $211 in Louisiana to $557 in Massachusetts.[15] Moreover, the United States needs a federal social assistant program for workers not covered by regular unemployment insurance or for those whose unemployment insurance expires. This includes such groups as new entrants and graduating students.

That these changes are desperately needed in the United States, has been confirmed by the recently passed Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act that extended and expanded unemployment compensation in three critical ways. First, states have latitude to waive work-search requirements for unemployment insurance recipients whose ability to search for work is impeded by the pandemic. Second, the Act extended the length of benefit by 13 weeks for those affected by the pandemic while also increasing the benefit amount by $600 per week. Third, the Act expanded eligibility to workers in nonstandard employment relationships such as independent contractors, gig workers, and the self-employed. Moreover, the Act created the Pandemic Unemployment Assistance program for workers not eligible for unemployment insurance. That all being said, these new provisions end on July 31 (increased benefit) and December 31, 2020 (expanded eligibility) respectively. If the systems in place were already adequate, there would not have been the need to go to such great lengths to bolster them during this time of economic crises on account of the coronavirus. For the United States, this alone implies a tacit need for reform.

Conclusion

The nature of employment has been changing, and the regular full-time job is increasingly being replaced by various forms of non-standard employment and by people engaged in a portfolio of activities.[16] The challenge is that our social protection systems have not kept pace with the changing nature of the labor market. Never have the repercussions of insufficient income security for all been as pronounced as they are now. Of course, the degree of severity varies greatly from country to country and this hinges on the design of policies and generosity of benefits. But countries like the United States and the United Kingdom demonstrate what happens when policymaking is guided by a discourse based on who is perceived to deserve benefits—the hardworking—versus who is perceived as undeserving of benefits—often racialized with blame placed on one’s behavior, i.e., lazy, as opposed to understanding underlying structural challenges to labor market entry. The silver lining to the coronavirus is that it presents an opportunity to implement much needed and long-awaited reforms to social protection systems in the United States and in Europe. Sadly, it took a devastating health pandemic for everyone to see what many of us have known for a long time. That income security for too many families, both in the United States and in some European countries, has simply become too little. That indeed, economic, social, and health suffering during this pandemic could have been greatly alleviated, had the right systems been in place, had they been well-funded and well-administered all along. We know this, because in those countries that have more generous social protection systems, we see less needless suffering. Every country is taxed beyond their limits in these unprecedented times. And indeed, measures well beyond what are outlined here are needed to respond to such an unprecedented economic crisis. But it is also important to recognize that foundational systems need to be in place that are better able to respond to labor market change and new social risks regardless. In the United States, we have seen what happens when benefits are limited in coverage, length, and amount when such a crisis hits. When the foundation is not in place, the fall is that much harder.

[1] In the first 1989 edition I outlined the trends in the rise in wage inequality and precarious employment as sources of economic inequality in the United States and in Europe.

[2] The government’s definition of unemployment typically requires people to be actively looking for work. The unemployment rate does not reflect the millions still working who have had their hours or their pay cut.

[3] Elise Gould, “A waking nightmare. Today’s jobs report shows 20.5 million jobs lost in April,” Economic Policy Institute, May 8, 2020.

[4] Social Insurance, social assistance and basic income (i.e., a child benefit for example) are the classic components of social protection systems.

[5] Kim Van Eyck “Flexibilizing Employment: An Overview,” SEED Working Paper 41, International Labour Organization, 2003.

[6] Hartley Dean, “Divisions of Work and Labour” in H. Dean and L. Platt (eds.), Social Advantage and Disadvantage, Oxford University Press, 2016. See also David Brady and Thomas Biegert “The Rise of Precarious Employment in Germany,” SOEPpaers, The German Socio-Economic Panel Study at DIW Berlin, 936-2017.

[7] Guy Standing, The Precariat: The New Dangerous Class, Bloomsbury, 2011.

[8] Abigail McKnight, “Low-paid Work: Drip-feeding the poor,” in J. Hills, J. Le Grand and D. Piachaud (eds), Understanding Social Exclusion, Oxford University Press, 2002).

[9] Atkinson, Inequality, 2015.

[10] Andrea Brandolini and Eliana Viviano, “Extensive versus Intensive Margin: Changing Perspective on the Employment Rage,” paper for conference on Comparative EU Statistics and Income and Living Conditions (EU-SILC), Austria, Vienna, December 2012.

[11] Atkinson, Inequality, 2015.

[12] Economic Policy institute, Fixing unemployment insurance and the coronavirus response, 2020.

[13] H. Xavier Jara and Holly Sutherland, “The Effects of an EMU Insurance Scheme on Income in Unemployment” in Designing a European Unemployment Insurance Scheme, Intereconomics, Number 4, 2014.

[14] OECD (2020), "Benefits in unemployment, share of previous income" (indicator), https://doi.org/10.1787/0cc0d0e5-en (accessed on 21 May 2020).

[15] Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, Policy Basics: Unemployment Insurance, May 2020.

[16] Atkinson, Inequality, 2015.