Democracy Vouchers

Seattle, United States

The Action

The Democracy Voucher Program offers a new way for Seattle residents to participate in local government by supporting campaigns and/or running for office themselves. Seattle is the first city in the United States to try this type of public campaign financing. The Seattle Ethics and Elections Commission (SEEC), a nonpartisan and independent commission, administers the Democracy Voucher Program.

The process for participation is simple. The SEEC distributes four democracy vouchers, each worth $25, to all eligible Seattle residents. The democracy vouchers are essentially pre-paid donations that the resident can make to the campaign of any candidate running for city office, which are listed on a “participating candidates” page. Residents then assign vouchers by writing in the eligible candidate’s name, date the voucher was assigned, and the resident’s signature. They can then return the voucher either directly to the candidate’s campaign or the SEEC.

In keeping with the goal of increasing transparency, all campaign contributions are public information. Each resident’s name and which the candidate(s) they give their voucher(s) to is published on the program data page.

Democracy Challenge

Participation in local elections is often low and Seattle is no exception. The objective of the voucher program is to give voters—many of whom have never donated to a political campaign—the opportunity to donate to a candidate of their choosing. The theory is that by donating to their candidate of choice, the voter will have a greater stake in the outcome of the race, which will in turn encourage them to vote and become more civically engaged overall.

How It Works & How They Did It

In the November 2015 elections, Seattle voters passed the Honest Elections Seattle (I-122) initiative, which included several campaign finance reforms as well as approval of a property tax of $3 million per year to fund the Democracy Vouchers program. Local advocates created the “Honest Elections Coalition” and drafted the legislation, making this a citizen-led initiative. The tax applies to commercial, business, and residential properties. For the average homeowner, the Democracy Voucher program costs a mere $8.00 per year.

Seattle’s city elections are nonpartisan, so there were no apparent traditional partisan divisions regarding support for the Democracy Voucher program. Roughly two-thirds of voters approved the initiative, and some of the hesitancy among the remaining third has been attributed to a lack of understanding of the program’s intent and mechanics.

How’s It Going?

According to a 2018 article by Vox, the democracy voucher program had a startup cost of about $1 million and resulted in residents returning $1.1 million in democracy voucher donations. Of the Seattle residents who were eligible to use the vouchers, only 3.3 percent did. However, an estimated 84 percent of the people who did use the vouchers had never given to a political campaign before, and for those who did participate, being able to donate to a campaign gave them a sense of agency and importance.

According to René LeBeau, Seattle’s Democracy Voucher program manager, the use of vouchers has increased each year. However, because the program is new, it is too soon to determine its impact on races for any particular office. There have not been two city council elections since the program began, which does not allow the city so far to compare turnout and use of vouchers across election cycles.

One explanation for increased use of vouchers is that over time, messaging around the program improved. During the first few election cycles that the vouchers were in use, vouchers were often framed as a mechanism for “getting big money out of politics.” This is a desire shared by many Americans; since the Citizens United Supreme Court decision, which undid historical campaign finance restrictions and enabled corporations and other groups to spend unlimited funds on elections, the extremely wealthy have held disproportionate sway over election outcomes in the United States. Early messaging around the voucher program cast it as a counterbalance to that influence, but this set unrealistic expectations for the program since the $3 million allocated for the vouchers can easily be outspent by the wealthiest individual or corporate donors.

Over time, the city has regained control of the narrative and communicated the original intent of the program: not to get big money out, but to get ordinary people in. In the words of René LeBeau, the Democracy Voucher program manager, the underlying logic of the project is straightforward and has been very well-received: “These are local offices, these are local issues, they should be using local money, with local contributors.”

That message, once it caught on, proved to be extremely resonant with the public. Many voters who had never had the means to donate to a campaign took pride in their newfound influence and became more engaged in the races. In the 2019 election cycle, increased attention to campaign financing impacted outcomes: because voters were paying more attention to campaign financing than before, the candidates who were backed by corporations and wealthy individual contributors fared worse that the candidates whose campaigns relied on smaller campaign contributions and vouchers, who were seen as more representative of voters’ interests.

As the voucher program has become more entrenched, both new and incumbent candidates have become more likely to participate in the voucher program. Though vouchers limit the maximum value of individual contributions and the total allowed fundraising by candidates, most candidates still sign up for the program because of the social good it does by involving the public and strengthening democracy.

Considerations

- Legal expertise. Any city or advocacy group looking to design a democracy voucher program must have a thorough understanding of applicable national and subnational campaign finance laws.

- Funding and staffing. Cities should decide early on how the program will be funded, how it will be staffed, and the scope of work for the staff. In the City of Seattle, the program is funded by a property tax, and the office that runs it is completely independent from elected officials. Staff dedicated to the program provide customer-service as well as IT troubleshooting, which can be time-consuming. Cities looking to implement similar programs should consider staff capacity when budgeting and plan to hire additional staff as needed.

- Civic education. The goal of the voucher program is to get new people involved in politics, which implies that many of them will have questions about the process. Therefore, voucher programs should be supported by strong civic education and resources for first-time political candidates, who may need guidance as they navigate the complex world of campaign finance.

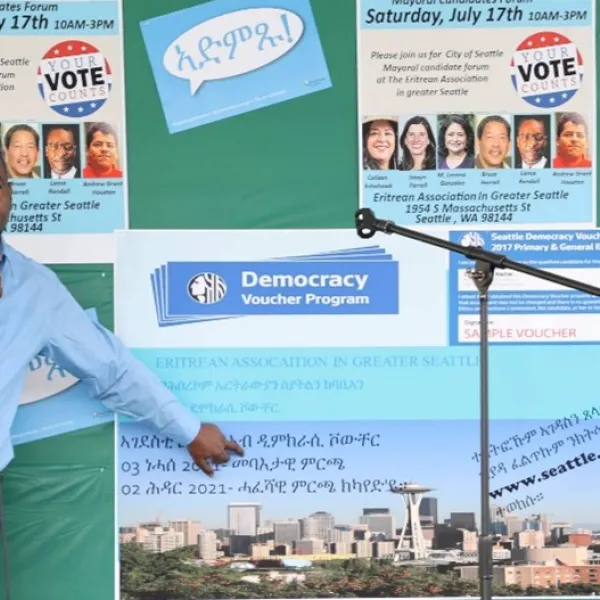

- Community outreach. Cities implementing voucher programs should plan how they will engage residents to ensure that everyone who is eligible to participate knows how to do so. Coordination with local nonprofits and advocacy organizations can be tremendously helpful in this effort. Outreach and education are particularly important for groups with low participation rates, such as ethnic/racial minorities and noncitizens who are eligible to participate (in Seattle’s case, legal permanent residents). In the United States, legal permanent residents are permitted to contribute funds to political campaigns, provided that the contributor is over the age of 18. For Seattle immigrant advocacy groups, the vouchers were seen as an excellent way to get legal permanent residents involved in local governance, and efforts to raise awareness of the program are ongoing.

Point of Contact

René LeBeau

Democracy Voucher Program Manager

Seattle Ethics and Elections Commission

[email protected]

Wayne Barnett

Executive Director

Seattle’s Ethics and Elections Commission

[email protected]

Who Else Is Trying This?

As the City of Seattle states on its website, it is the first city to implement a democracy vouchers program. Previously, the most similar innovation was the establishment of “clean elections” funds, which several US states have set up. These involve giving state funding to candidates who agree to forgo traditional donor funding.

- Arizona, US: The Clean Elections Act provides a clean funding program for statewide and legislative candidates who agree to forgo special interest and high contributions if they raise a minimum number of qualifying contributions.

- Maine, US: The Maine Clean Election Act established a voluntary program of full public financing of political campaigns for candidates running for governor, state senator, and state representative in 1996.

- Connecticut, US: The Citizens’ Election Program provides clean elections financing to qualified candidates for statewide offices and the General Assembly, financed primarily by a combination of donations and the proceeds of the sale of abandoned property in the State of Connecticut’s custody.

Some cities have implemented alternative programs for public financing of elections to encourage greater participation in local government elections.

- New York, US: Donations of up to $175 for city council and mayoral races are matched with public money at a ratio of 6:1, which has been linked to greater diversity among both donors and candidates. Numerous other cities have instituted similar versions of this program with varying levels of success.