Make Voting a (Family) Tradition

Minneapolis, United States

The Action

Make Voting a Tradition (MVAT) is a culturally specific, year-round, multi-generational approach to increasing voter turnout and civic engagement.

The fundamental principle of MVAT is that Native Americans are more likely to become politically active when engaged by peers. Relying on a small staff as well as paid community volunteers, MVAT partners with local, statewide, and national efforts to increase native voter turnout. Volunteers and staff register voters, assist with civic education, and organize candidate meet-and-greets. Through these initiatives, MVAT has mobilized Native Americans, an often-marginalized group, and helped them to realize their power to shape public policy.

Democracy Challenge

Native Americans are a powerful voting bloc in Minneapolis, but the group has faced systemic barriers to political participation. For centuries, the US government has advanced policies aimed at eradicating native cultures and peoples, restricting their right to vote, and denying pathways to citizenship. Even today, there are laws in place that restrict access to the polls. Recognizing this legacy, MVAT relies on native volunteers, rather than outsiders, to collaborate with their peers in the electoral process and in political activism, and to lead civic education efforts.

How It Works and How They Did It

The key factor that differentiates MVAT from other campaigns is its name: “Make Voting a Tradition”. As Native American Community Development Institute (NACDI) President Robert Lilligren explains, “many Native American cultures emphasize the importance of the collective and respect for elders, so making voting into an intergenerational tradition is one way to ensure that native voters will show up consistently and encourage future generations to follow suit.” Unfortunately, because older Indigenous people have faced archaic forms of discrimination— many were enrolled in residential schools—MVAT volunteers have trouble convincing them to trust the political system and see it as a force for good. MVAT consequently focuses many of its initiatives on reaching young people, especially teenagers who are not yet eligible to vote. Volunteers provide civic education and encourage young people to discuss politics with their families, especially issues that directly impact their communities and tribes. Engagement with young people helps them to develop a habit of voter participation, and many successfully persuade skeptical elders to accompany them to the polls. Especially since the onset of the pandemic, younger generations have also helped bridge the technology gap, often assisting their grandparents, aunts, uncles, and parents with online tools, such as those that process voter registration.

MVAT also works to establish trust with community members and local organizations. The group aims to portray voting as part of a sustained national engagement effort that keeps connections thriving between election days, rather than just during political campaigns.

“Trust-building in a community that is traumatized takes a very long time, and you must be consistent. You have to show up constantly,” explains Elizabeth Day, NACDI’s community engagement programs manager. “We are non-partisan. We are not telling you who to vote for. All we are doing is giving you the education and information that you need to feel successful when you go to the polls to vote.”

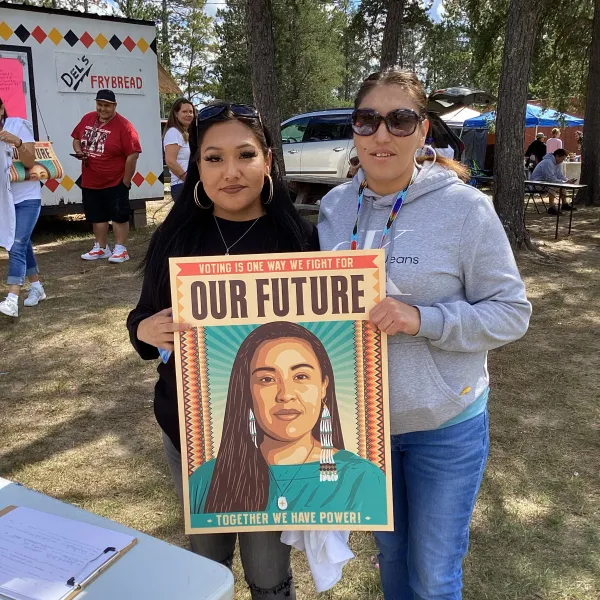

Voter registration and get-out-the-vote campaigns are a crucial component of MVAT. The group leads door-to-door canvassing efforts, but also employs less common strategies, such as taking volunteers on trips and “tabling” (setting up tables where people can interact with MVAT volunteers) at powwows and other cultural and social events in the Twin Cities area. Because these events are already heavily attended, MVAT can reach many people by joining them. During American Indian Month (which Minnesota celebrates each May), nearly every Native organization hosts events, and MVAT tries to be at all of them, providing information and registering voters.

How’s It Going

Because the Native American population of Minneapolis is relatively small (between 1 percent and 2 percent of the population) and understudied, trend data on voter turnout is limited. One MVAT initiative is to build a new, statewide database to collect that missing information. MVAT was also a key partner in the 2020 US Census and redistricting efforts. Despite the data gaps, program leads have years of anecdotal evidence indicating increased enthusiasm and engagement.

Highlights include:

- Civic education: Beyond elections, MVAT offers a variety of civic education workshops. Minneapolis, for example, is one of the few cities in the United States using ranked choice voting, so MVAT organized an event to explain the process using a sample ballot.

- A unique approach to organizing candidate forums: Robert Lilligren, a former city councilmember, worked with MVAT staff and volunteers to create an open-air “speed-dating-style” forum with the candidates, during which community members had the opportunity to meet the candidates and pose questions. This was well-received by the community and is likely to become a model for future candidate outreach.

- Advocacy for the rights and interests of Native Americans: MVAT engages in policy advocacy when the rights and interests of Native Americans are at stake. For example, MVAT campaigned for Indigenous People’s Day to be officially recognized as a holiday, first by the city of Minneapolis and eventually at the state level.

- Voter rights: MVAT is engaged in voting rights work, particularly during election season. MVAT volunteers registered approximately 109 unsheltered Native people living in an encampment called the “Wall of Forgotten Natives.” This camp housed up to 300 people at a time and straddled jurisdictions, so local MVAT volunteers helped camp residents navigate the process of same day voter registration. Camp residents were unlikely to have identification or proof of address, but volunteers advocated for their status as members of the community entitled to a vote.

- Community partnerships: In 2020, MVAT partnered with the Native American Community Clinic to develop information addressing vaccine hesitation that volunteers could distribute while canvassing.

Considerations

- Applications in other BIPOC communities: The peer-to-peer engagement model distinguishes MVAT from other voter registration efforts and can be replicated in other communities where trust in government is low, particularly where there is a history of marginalization and discrimination.

- Mutually beneficial partnerships are key: The more partnerships you can make, and the more consistently you can work together and share resources for the common good, the better off all the organizations are going to be. NACDI, for example, did not copyright any MVAT resources, but makes them openly available for other groups to use (and they have been).

- Early data collection: Data is especially important, especially to funders. Figuring out what to collect and how (and doing that as soon as possible) is important to solidify a project’s success.

Point of Contact

Robert Lilligren

President and CEO, NACDI

[email protected]

+1 (612) 284-1091

Elizabeth Day

Community Engagement Programs Manager, Make Voting a Tradition

[email protected]

+1 (612) 235-4971

Who Else Is Trying This?

- California, US: The California Native Vote Project is building Native American political power through an integrated voter engagement strategy throughout native communities in California. The group does this through education, outreach, and census advocacy.

- United States: APIAVote’s Alliance for Civic Engagement is a network of local partners throughout the United States that benefit the Asian & Pacific Islander American community. The group helps the community by creating voting education programs and organizing voter contact campaigns.