All Quiet on the Moldovan Front

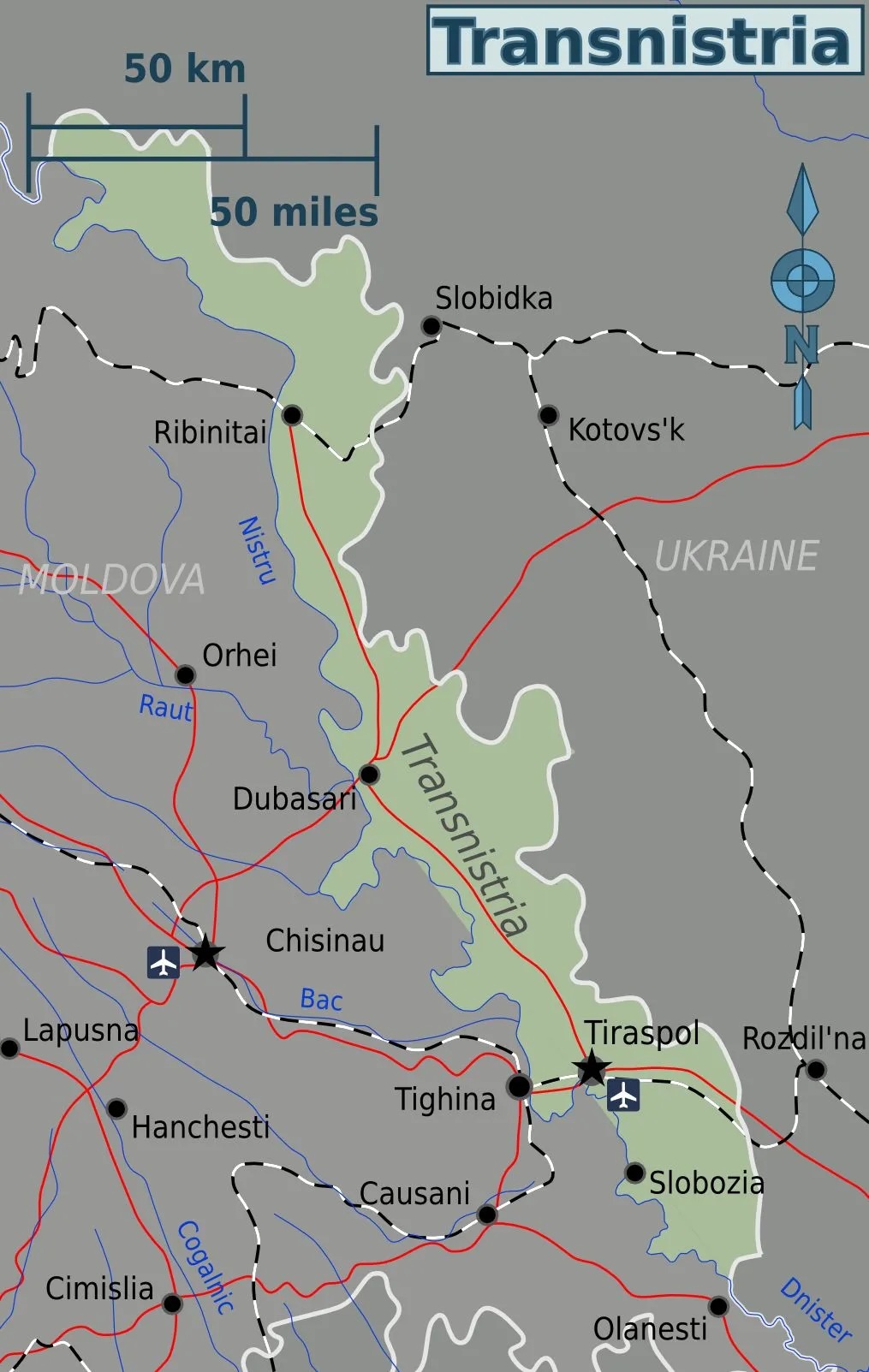

The 28 February congress took place amid a tense atmosphere. The authorities in Tiraspol – the capital of Transnistria – have been seething since 1 January, when a new Moldovan customs code took effect, obligating companies in the Transnistria region to pay customs duties to the state just as any other Moldovan company.

The assembled deputies claimed that Chisinau had unleashed an “economic war” on the region. Russia’s Foreign Ministry weighed in, declaring, “Protecting the interests of the residents of Transnistria, our compatriots, is one of our priorities.”

Transnistrian officials reacted angrily to the imposition of new customs duties, which could raise prices both for imports and the region’s exports to Moldova and the European Union. Their response included threats to tax farmers in Moldovan-controlled parts of the divided Dubasari district. These farmers would be obligated to register as economic agents under the jurisdiction of the unrecognized administration on the left bank of the Dniester, including the requirement to open bank accounts there. Equally serious were threats to restrict education in Romanian.

Their consternation can be interpreted as a reaction to the new realities concerning trade and customs relations, but also that they sense that other measures will follow that could undermine Transnistria’s economy. In trade terms, the breakaway region gained from the 2014 Association Agreement between Moldova and the EU, which led to a drastic shift of its export market from Russia to the EU.

The event itself put the damper on the fires of speculation. The deputies did ask the Russian Duma to “implement measures for defending Transnistria amid increasing pressure from Moldova, given the fact that more than 220,000 Russian citizens reside in Transnistria,” but they did not plead to be allowed into the Russian Federation.

- December 2023: EU leaders approve opening membership negotiations with Moldova, despite the unresolved status of the unrecognized, Russia-backed Transnistria territory

- February 2024: Transnistrian leader Krasnoselski calls a “congress of deputies at all levels” to discuss the “pressures exerted by the Republic of Moldova” on the territory

- 28 February 2024: The congress passes a resolution appealing to the Russian parliament to “implement measures for defending Transnistria amid increasing pressure from Moldova”

- 29 February 2024: Contrary to speculation, Russian President Vladimir Putin makes no mention of Transnistria in his annual address to the nation

- 6 March 2024: The governor of Moldova’s autonomous, largely Russian-speaking Gagauzia region complains to Putin in Moscow “about the illegal actions of the Moldovan authorities” toward the region

A Step-by-Step Strategy

Piecing out what the Transnistrian authorities intended by calling the extraordinary congress requires a look into their strategy, if that is the right word, for relations with Chisinau. It is not always easy to penetrate the smoke and mirrors of disinformation and threats of blackmail that emerge from the region. Overall, it seems that Tiraspol has a plan to thwart Chisinau’s efforts to reintegrate the region.

The expressions of anger and surprise when the customs regulations took effect on 1 January are one plank in the strategy. But since a revised customs code was approved in 2021, there should be no surprise.

Another step is the adoption of a “victim” position, most recently referenced by Krasnoselski’s assertion that the region is being economically strangled by Chisinau.

The third step is Tiraspol’s insistence on negotiating with the Moldovan government only through the “5+2” format, knowing only too well that the government prefers the “1+1” format under the aegis of the OSCE, without the presence of the aggressor state, the Russian Federation, which has maintained a small force of “peacekeepers” in Transnistria since the 1990s.

The purportedly genuine protests by Transnistrian trade unions and companies against the new customs duties look suspiciously like another tool in Tiraspol’s strategy. While protesters tried to distance themselves from the authorities, Moldovan news reports have suggested the involvement of people close to the region’s “president” Vadim Krasnoselski and Victor Gushan, who heads the Sheriff conglomerate that dominates the territory’s economy.

The next steps depend on the reaction of the authorities in Chisinau, indications from Moscow, and the personal decisions of Gushan, the de-facto ruler of Transnistria, who rarely if ever makes public statements on politics.

This strategy aims to get Chisinau to abandon trying to reintegrate Transnistria, roll back the customs duties, and stop what Tiraspol sees as efforts to control the breakaway region and make it dependent on Chisinau.

Beyond the departure of Russian troops, Chisinau aims to incorporate the institutional system of Transnistria into that of Moldova. This could be partially accomplished with a joint budget covering both banks of the Dniester and resolving issues such as managing pensions between the central banks currently operating in both territories. Transnistria has all the institutions of a consolidated state and it will be difficult, however, to convince it to dismantle the police, army, and parliament.

The Real Law on the Left Bank

The recent speculation about whether the Transnistrian region would request Russian annexation hardly came as a shock, as similar rumors have circulated in the past. These rumors, often initiated by the Tiraspol authorities and amplified by Russian media channels, serve several purposes, but rarely have direct legal consequences. The reality is that it is the de-facto administration of Transnistria – the Sheriff conglomerate, headed by Victor Gushan – that controls the political processes on the left bank of the Dniester, and the prosperous business that Sheriff has in Tiraspol and the income Gushan enjoys from exports to EU countries simply cannot co-exist with the supposed wish to become part of Russia, as this would immediately destroy the EU-focused economy of the separatist region, as well as considerably reduce the oligarch’s wealth.

These moves and statements can be interpreted from several perspectives. A formal request by Transnistria to join the Russian Federation, should this ever transpire, would represent a significant escalation of separatist rhetoric, with the potential to deepen the gulf between Transnistria and Moldova and hamper the current Moldovan government’s policy of joining the EU. More likely, these gestures are part of a broader negotiating strategy aimed at pressuring Chisinau and its international partners for certain political or economic concessions, especially the cancellation of import duties for firms in Transnistria, if not a halt to reintegration efforts and the resulting increasing dependence on Chisinau.

It should be stressed that, although the rhetoric may seem alarming, similar events in the past have shown that there is a significant distance between the provocations and blackmail of separatist leaders and concrete changes in Tiraspol’s policy, namely the 2006 referendum on independence. This referendum was called following the previous “all levels” congress.

Even if Transnistria were to formally join Russia, through a referendum or otherwise, its full political and economic integration into Russia might depend on Moscow’s ability to project its control through military means, across hundreds of kilometers of Ukrainian territory. The 1,500 or so Russian troops stationed in Transnistria are not capable of posing a significant military threat to Ukraine, but only to Moldova, at the moment an unlikely scenario.

This article first appeared in Transition Online