Creating a Transatlantic Bridge Builder

Without the billions of dollars of the European Recovery Act, it is likely that the war-torn continent would not have rebounded so successfully, nor that Germany or other European countries would have turned into stable democracies and close US allies.

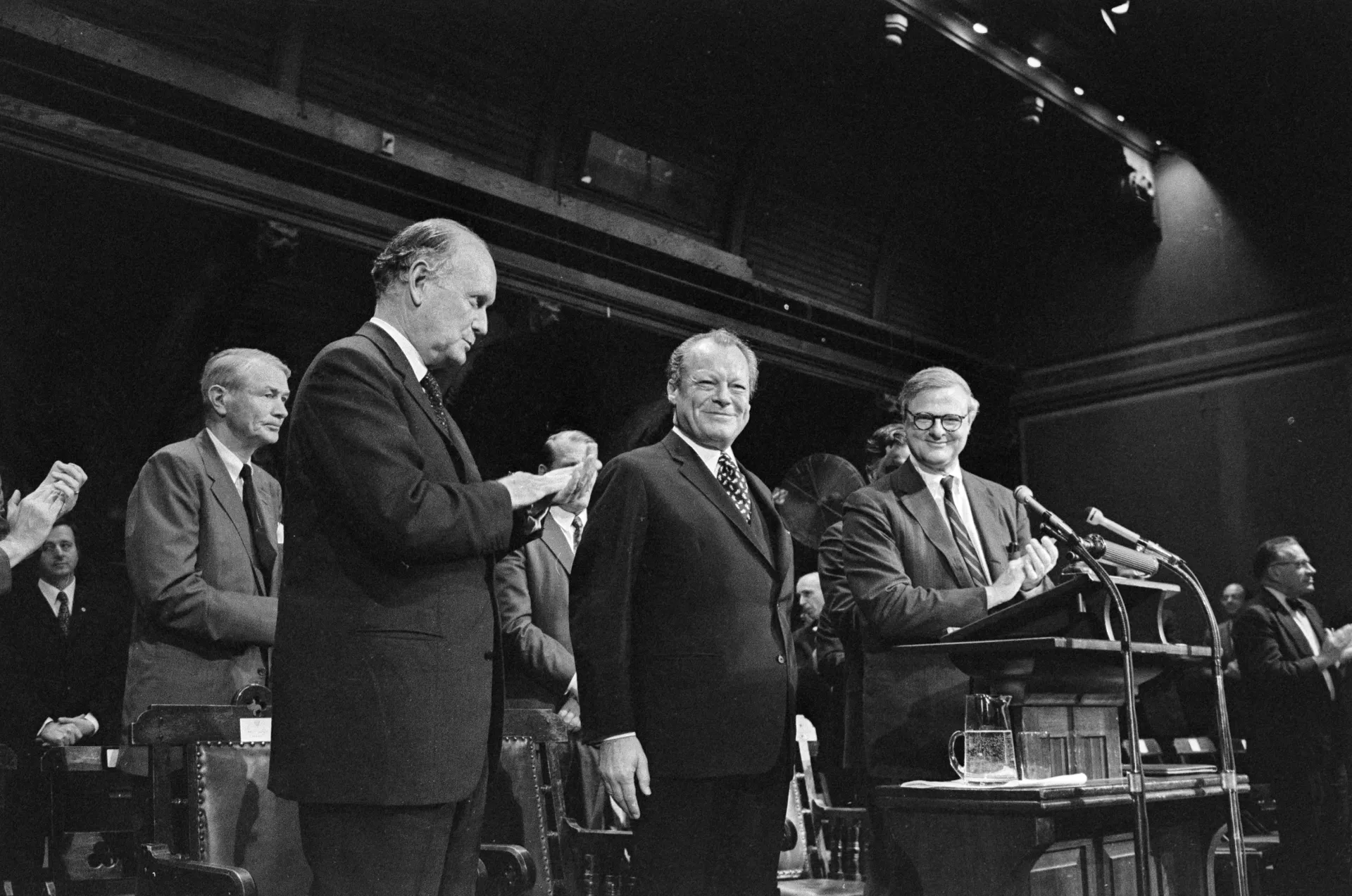

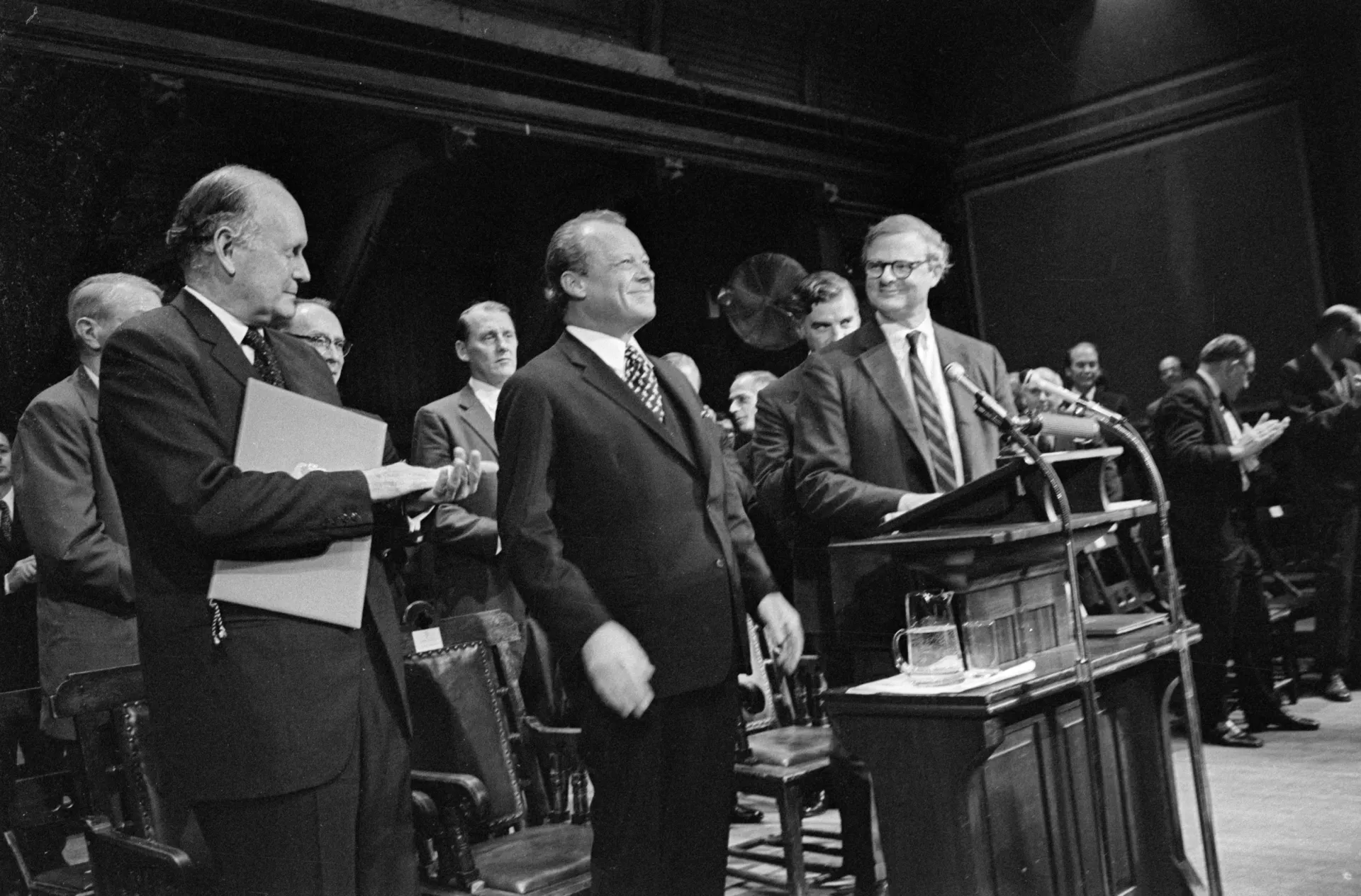

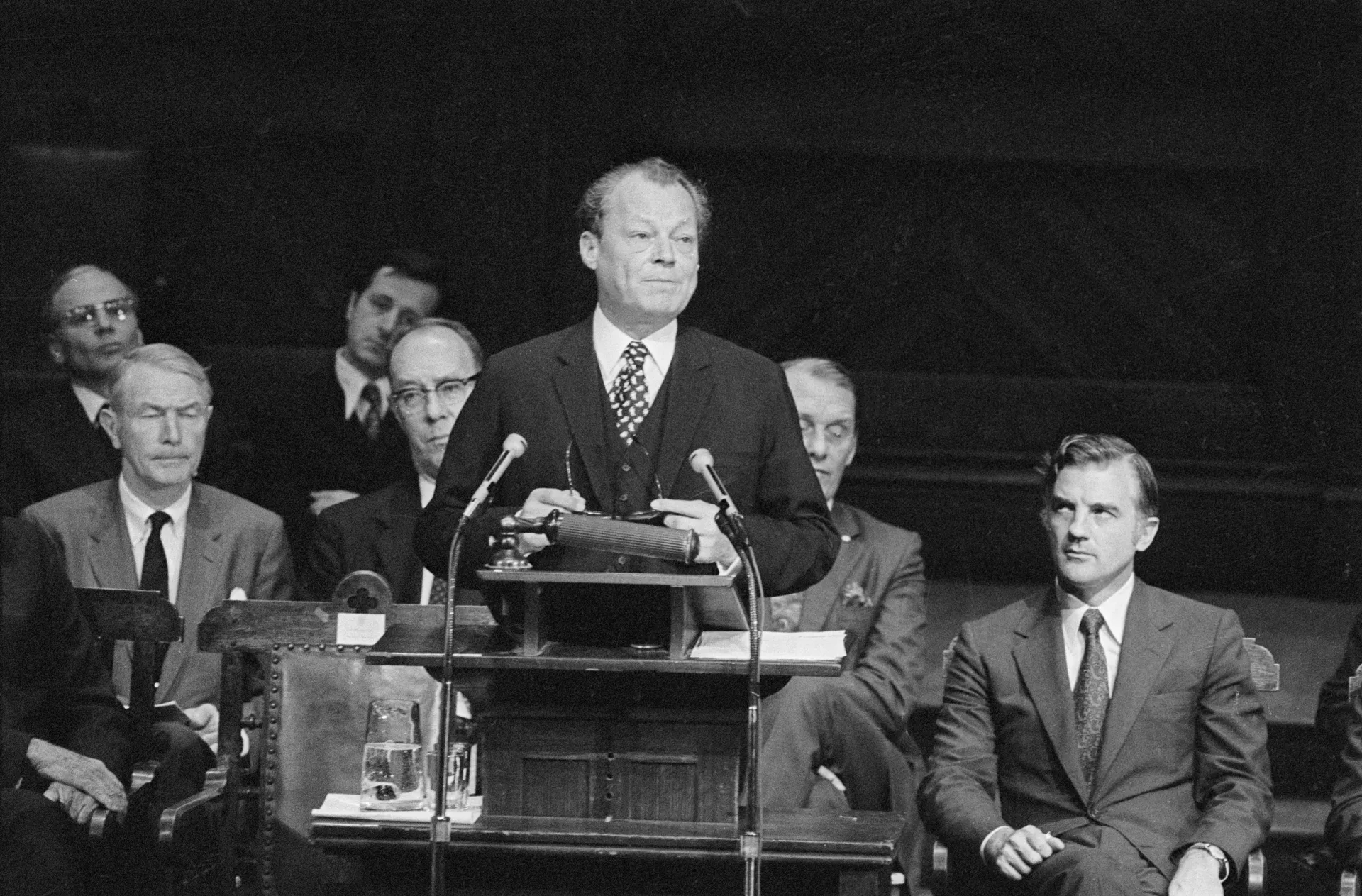

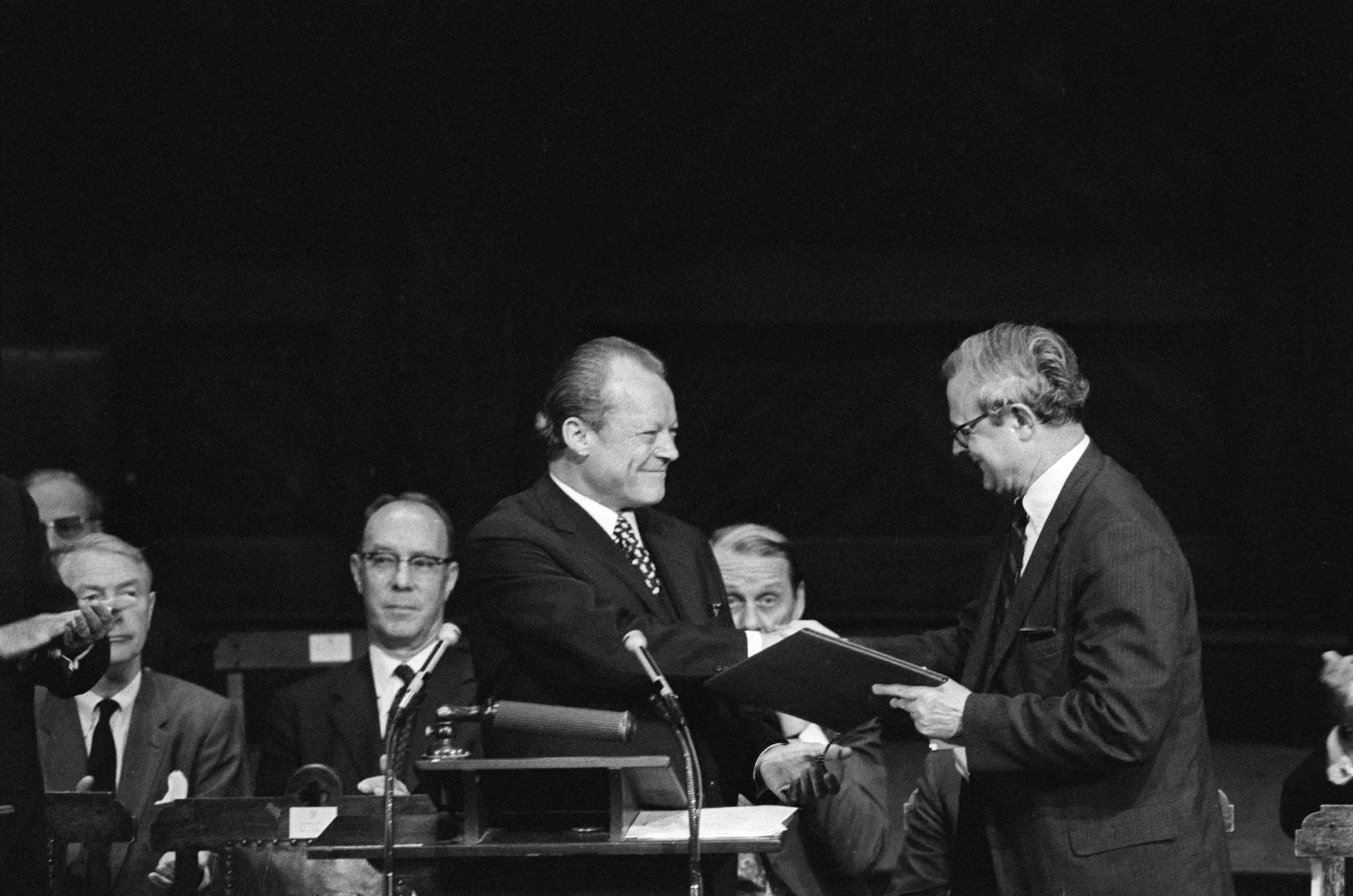

On another bright day at the very same university—exactly 25 years later, on June 5, 1972—West Germany’s Chancellor Willy Brandt presented a check for 150 million Deutschmarks as a gesture of gratitude to the American people. It was the birth of the German Marshall Fund of the United States (GMF), a new transatlantic bridge-builder, celebrated in a ceremony at Harvard University’s Sanders Theatre.

In 1947, Europe was on the brink of economic collapse, and military tensions between Washington and Moscow were growing. “It must be the policy of the United States to support free peoples,” President Harry S. Truman announced when he signed a congressional bill committing the United States to confronting the Soviet Union’s growing influence. This became known as the Truman Doctrine.

In 1972, the United States and Europe were again in the midst of an economic crisis. Americans and Soviets were amassing arms and waging a proxy war in Vietnam. When Brandt declared at Harvard University that peace needed to be “secured through cooperation” and that the creation of GMF would be a contribution to this task, he was well aware of the fragility of the transatlantic relationship, and of that between Germany and the United States in particular.

Among Brandt’s guests of honor was Guido Goldman, director of Harvard’s Center for European Studies and GMF’s founding father. The son of German Jews who had fled the Nazis in 1940, Goldman could not have agreed more with the chancellor. The Marshall Plan had helped to create close ties between Europe and the United States, but Goldman worried that these bonds were losing relevance for a new generation—at Harvard University, he had witnessed the waning of these ties. Goldman, a close friend of Germany and a man of great determination, felt the need to act.

In 1970, with the Marshall Plan anniversary two years away, Goldman had a brilliant idea: What if Germany reciprocated the initial gift from the United States with a smaller donation of about 3 million Deutschmarks to his Harvard institute? The Center for European Studies was suffering from the dwindling interest in transatlantic relations and desperately needed new funding.

Goldman flew to Germany to present his plan to West Germany’s finance minister. Alex Möller, a Social Democrat, had been an early opponent of Hitler and had staunchly backed the Federal Republic’s integration into the West.

“Would Germany’s government be willing to help Harvard out, in honor of George C. Marshall?” Goldman asked the finance minister. They had a friendly chat over a good deal of scotch and, before the evening ended, Möller said that, as a thank-you gesture, he had a much larger amount than 3 million in mind. “How much?” Goldman wanted to know, intrigued. “About 250 million Deutschmarks,” Möller replied. Goldman could hardly believe his ears, but the finance minister insisted.

For some time, Goldman thought Möller’s plan was a fantasy. But not long after, Möller came to the United States and asked him if he already knew what he wanted to do with the money. Goldman spontaneously pitched the idea to establish a US foundation, a convener and grant-maker to support transatlantic cooperation and projects. Möller was impressed.

For some time, Goldman thought Möller’s plan was a fantasy. But not long after, Möller came to the United States and asked him if he already knew what he wanted to do with the money.

Goldman also needed to convince the US government. After all, the Marshall Fund was to be a US foundation, based in Washington. It would not be an easy task. President Richard Nixon did not particularly like Germany’s chancellor and mistrusted his Ostpolitik aimed at détente between Western and Eastern Europe.

Brandt not long after visited Washington. Having met with Nixon, he noted: “I spoke to N. [Nixon] about proposals to create a Marshall Memorial fund to mark the 25th anniversary of the Marshall Plan’s announcement, linking this to a new American Council for Europe and financial support for European studies. N. thought this a welcome idea.”

By the time Brandt presented the German gift at Harvard University, the proposed sum had shrunk to 150 million Deutschmarks. Nonetheless, Goldman was pleased—3 million Deutschmarks for his Harvard institute plus 147 million for the new foundation was an enormous amount.

“American-European partnership is indispensable if America does not want to neglect its own interests,” Brandt said at Harvard on June 5, 1972, “and if our Europe is to forge itself into a productive system instead of again becoming a volcanic terrain of crisis, anxiety, and confusion.”

This message was true then and it is true today, as GMF celebrates its 50th anniversary and the Marshall Plan its 75th anniversary. The Ukraine war is a stark reminder that Western unity is an essential element of Western power.

But such unity does not come naturally, given often divergent interests and perspectives. A transatlantic mediator and bridge builder like GMF remains eminently important in such consequential times.

Next | Who Put the German in German Marshall Fund?

Though it was established with German funds, Guido Goldman did not aim to build an organization that would focus solely on German concerns. In his mind, the new US institution would promote European issues and comparative work on transatlantic challenges.

Previous | In Fellowship We Find Leadership

When John W. Boerstler, who was working to improve care for US veterans in Houston, Texas, was selected as a Marshall Memorial Fellow in 2011, he did not predict that he would soon make history helping to build a veterans ministry in war-torn Ukraine, the first of its kind in Europe.

This year the German Marshall Fund marks its 50th anniversary and the 75th anniversary of the Marshall Plan. These historic moments serve as an opportunity to highlight the achievements of one of the most important American diplomatic initiatives of the 20th century and how its legacy lives on today through GMF and its mission. Learn more about GMF at 50.