France and Germany Carry Same Sentiments that Put Trump in the White House

Since President Donald Trump took office there has been on both sides of the Atlantic a growing debate over the health of democracy in the United States, and about the course U.S. politics could take under an administration dominated (so far) by national-populists. Across Europe, the political mainstream has also been facing strong challenges from various nationalist-populist actors of the left and the right. In the longer-established European democracies, a resulting impact comparable to Trump’s election has already been seen in the British vote to leave the EU. As elections near in France and Germany, Europeans brace themselves to see how strongly national-populist forces will perform in the two most important EU members.

Most European observers who fear the consequences of the rise of national-populists, already aghast at the evolution of the U.S. presidential election, comfort themselves that the Front National and the Alternative für Deutschland stand no chance of getting near the levers of power. That is most likely true and is backed by latest polls. However, it would be complacent to overlook that some of the key opinions that fueled the Trump phenomenon are also present in France and Germany — often to an equal or a higher degree.

The political scientist Daniel Drezner notes that the United States under Trump now looks like other post-financial crisis democracies in Europe and elsewhere: “deeply affected by globalization, hostile to immigration, and receptive to populist nationalism.” This observation cuts both ways, though. Public opinion in solidly democratic European countries is not so different from that in the United States when it comes to some views normally associated to the rise of nationalist-populist sentiment.

This is supported by new survey data released by IPSOS MORI. The firm polled people in 23 countries, including nine EU members and the United States, and its findings paint mostly a picture of deep pessimism, popular dissatisfaction, mistrust in political institutions, and receptiveness to nativist solutions. Based on this data at least, the publics in the United States, France, and Germany — for all their political and social particularities — are not that far apart on key questions that touch upon the main drivers that helped Trump on his way to the White House.

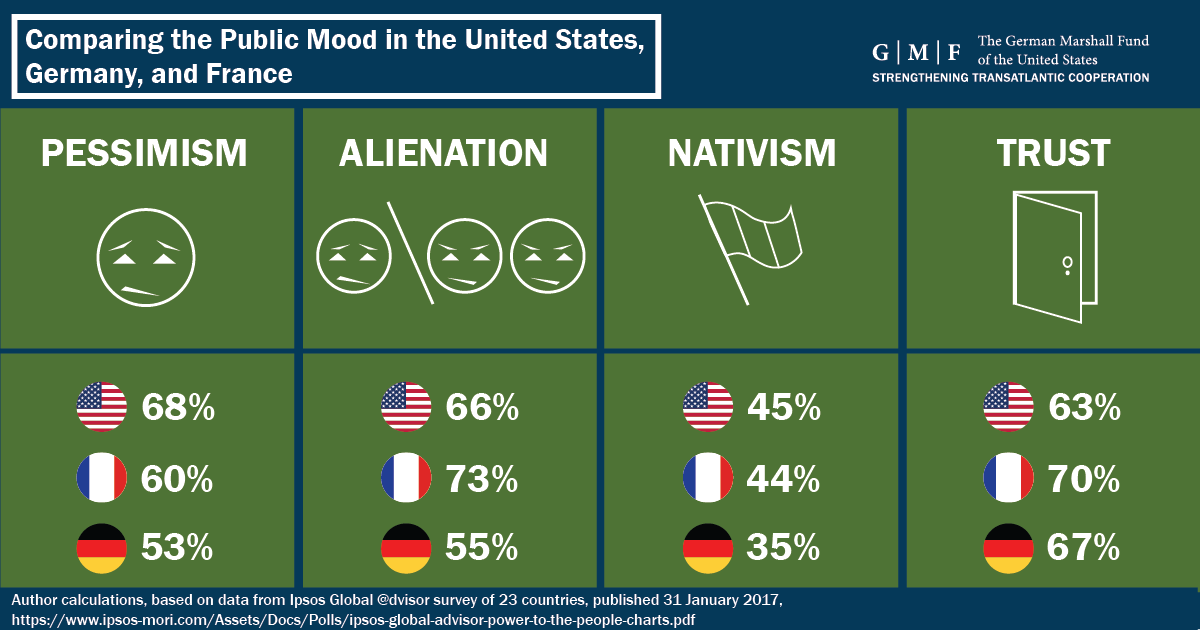

Majorities in all three countries said they are pessimistic about the state of their country and the future for themselves and their children. (However, in all three cases majorities also said their country could recover from decline, with Americans unsurprisingly the most optimistic there.) Averaging the “negative” scores for whether people consider their society to be broken and their country in decline, and whether they and their children will have better lives than previous generations shows the French to be more pessimistic than Americans and the Germans less so.

French, German, and U.S. citizens also expressed a clear degree of alienation from their elites, if one looks at their answers to questions about whether the economy is rigged toward the rich and powerful, whether traditional parties care about them and whether experts understand their lives. Again, averaging scores on these questions shows this is the case for clear majorities in the three countries, again with the French public appearing the most alienated.

Publics in the three countries expressed, however, a less negative view on two questions relating to globalization than might be expected from conventional wisdom. In each of them, about one-third said that opening up the economy to foreign firms and trade is a threat to the country. French and German respondents showed a similar level of concern over whether their country needed to take steps to “protect itself from today’s world” whereas nearly half of Americans take this view.

On different questions relating to immigration, mostly between one-third and half of respondents in France, Germany, and the United States endorsed what can be described as “nativist” views. Averaging the nativist scores on six such questions, France and the United States are virtually level with Germany clearly behind.

Respondents in all three countries expressed high levels of mistrust in the government, political parties, the media, and to a lesser extent the justice system. Averaging the “negative” answers regarding these four institutions shows the United States, German, and French publics to be close, with the European ones more mistrustful.

The above confirms, if it was needed, that some of the opinions that helped Trump become president are present to a broadly comparable extent in France and Germany. In fact, on most of the questions considered here, France scores higher than the United States.

Of course, one should not read too much from any single poll. It is also important to note that IPSOS MORI conducted its survey just before last November’s presidential election in the United States.

Now that Trump has taken office and started putting his nationalist-populist ideas in practice, it will be very interesting to see if this leads to a divergence between European and U.S. public opinions on some of the issues covered above. It may be that European publics will be put off by national-populist ideas now that they see some of them being put in practice in the United States. But one cannot rule out that seeing these ideas going from fringe to government policy will for some people make them more acceptable.

For now at least, it looks as though the major European democracies are in the same boat as Trump’s America in some ways, including the two core EU members that will this year find out the will of their electorates. As well as the current level of support nationalist-populist parties receive, France’s two-round presidential election system and Germany’s parliamentary system make their victory very unlikely. But, unless in the coming years there is a significant change in the kind of public opinion revealed by the latest IPSOS MORI survey, especially in France, these parties could easily grow further and knock louder on the door of government.

(For details of questions and individual country answers, see data from IPSOS MORI: https://www.ipsos-mori.com/researchpublications/researcharchive/3835/Six...)