The Future of the Quad and the Emerging Architecture in the Indo-Pacific

Summary

The Quadrilateral grouping of Australia, India, Japan, and the United States (the Quad) has come a long way from its origins, establishing itself as a crucial pillar of the Indo-Pacific regional architecture and significantly shifting in tone and focus from its early iterations. Since its revival in 2017, the Quad has been elevated to a leader-level dialogue, it has begun issuing joint statements, and it has developed a new working-group structure to facilitate cooperation. It has also significantly broadened and deepened its agenda to include vaccines, climate change, critical and emerging technologies, infrastructure, cyber, and space.

These recent changes to the Quad raise several questions about its future trajectory. What are the drivers of engagement, the domestic support, and the bureaucratic capacity in the four countries to continue investing in the Quad? How well does the Quad’s new working-group structure function, and will the working groups be able to deliver tangible results? How has the Quad’s agenda evolved, and will it return to its initial focus on security challenges? Are the Quad countries open to cooperation with additional countries and, if so, what form will this take?

This paper analyzes these questions drawing on recent publications, official statements, and interviews with key experts and policymakers in the four countries. In doing so, it offers five key takeaways into the Quad as an evolving part of the Indo-Pacific architecture, as well as a vehicle for achieving the goals of its four member countries.

Since its revival in 2017, the Quad has been elevated to a leader-level dialogue, it has begun issuing joint statements, and it has developed a new working-group structure to facilitate cooperation

First, in terms of institutionalization and internal goals, there is little interest among the member countries in further institutionalizing the Quad by establishing a secretariat or adopting a charter. All four consider the flexible nature of the grouping to be an asset. At the same time, the Quad partners have increased their alignment on strategic issues and aim to continue doing so in the near future by solidifying ties within the grouping.

Second, since the Quad countries’ immediate goals are related to strengthening the internal coherence of the grouping, there is little interest in membership expansion at this time. However, the Quad countries may be open to functional cooperation with additional countries on a limited basis in the future through specific initiatives and projects within working groups.

Third, the Quad appears to have a durable support base within its four member countries, suggesting that it will continue to be an important part of the Indo-Pacific institutional landscape in the future despite changes in administrations. The working-group structure and the broadened range of issues covered by the grouping has expanded the number of government agencies and individuals involved in its operations. This has helped the constituency of supporters for the Quad to grow beyond security policy circles in each country. There is also broad backing for the Quad and its activities across the political spectrum within the member countries.

Fourth, despite the expansion of the Quad agenda to include economic and nontraditional security issues, traditional security cooperation remains a key element of the grouping. The recently announced Indo-Pacific Partnership on Maritime Domain Awareness has important security implications. Moreover, while most public attention has focused on the six leader-level working groups addressing economic and nontraditional security challenges, cooperation on security issues such as maritime security as well as on cybersecurity, counterterrorism, countering disinformation, and humanitarian assistance and disaster response have continued at the ministerial or working level.

Fifth, there remain significant challenges for the grouping. As the Quad countries recognize, continuing to strengthen alignment and ties with one another is vital, as key differences in interests and priorities remain despite the partners’ shared interests. In addition, the grouping’s long-term survival will depend on its ability to marshall its structures and processes to deliver meaningful benefits to the Indo-Pacific. The Quad’s weakly institutionalized structure and different levels of bureaucratic capacity are challenges in this regard. Finally, it remains to be seen how the Quad will engage with other regional institutions and partner countries in order to achieve its ambitious goals.

Introduction

The Quadrilateral grouping of Australia, India, Japan, and the United States (the Quad) has emerged as a crucial pillar of the Indo-Pacific regional architecture. It is perhaps best described in the words last year of Australia’s then foreign minister Marise Payne as “a diplomatic networking of countries that engages flexibly and practically, with the clear purpose of enhancing stability and prosperity by meeting challenges quickly and nimbly.”1 Since its revival in 2017, the Quad has gone through several crucial changes. It has steadily been elevated from meetings among working-level officials to foreign ministers and, most recently, to heads of state. The Quad partners have increased their alignment on strategic issues, issuing joint statements since the first leaders’ summit in March 2021. The grouping has also become more formalized through new structures of cooperation, and its agenda has broadened and deepened to include not just security issues but also public goods like vaccines and issues such as climate change, critical and emerging technologies, infrastructure, cyber, and space.

The broadening of the Quad’s agenda—specifically the focus on the provision of public goods in the Indo-Pacific and the absence of overt references to the China challenge—has increased the interest of countries around the world in engaging with the grouping. The newly created Quad working groups have been seen by potential partners as promising avenues for cooperation. This was evident in the EU’s recently released Indo-Pacific strategy, which refers to collaboration with the Quad’s working groups.2 South Korea’s new leadership has indicated interest in doing the same.3

However, the rapid institutional development of the Quad also raises questions. Will the cohesion displayed currently by the Quad continue, and what are the drivers of participation of the four partner countries? What impediments could the grouping face, and how well is the new working-group structure functioning? How open are Quad countries to collaboration with other partners and what form could this take? Will the Quad return to its initial focus on security challenges? This paper aims to answer these questions and to understand the future of the Quad and its role in the emerging architecture in the Indo-Pacific, drawing on recent publications, official statements, and interviews with key experts and policymakers in the four countries.

Evolution of the Quad

Quad 1.0

The origins of the Quad can be traced back to the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami, after which Australia, India, Japan, and the United States coordinated their humanitarian assistance and disaster-relief responses through a Tsunami Core Group. This successful ad hoc effort was seen as a potential model for regional cooperation at the time. However, the four countries did not pursue this idea until a first exploratory meeting in 2007, when working-level officials met in Manila on the sidelines of the ASEAN Regional Forum. This meeting stemmed from a proposal by Japan’s Prime Minister Shinzo Abe—an early champion of the idea—and was designed to bring together “four countries that share some values and growing cooperation in the Asia Pacific.”4 This meeting was followed by a Quad maritime exercise in the Bay of Bengal later that year, which also included Singapore. “The expanded exercise was the last visible sign of the Quad” before it disappeared for almost a decade.5

The demise of the first iteration of the Quad was largely due to China’s criticism of the grouping, different levels of concerns about this criticism among the four countries, and domestic pressures and politics in each country that forced them to reconsider their involvement.6 Japan became lukewarm after Abe left office in September 2007, the United States seemed more interested in other forums, and Australia’s new government elected in in November 2007 objected to the Quad and was quite sensitive to China’s concerns. Moreover, a general lack of familiarity and habits of cooperation among the countries was also a key stumbling block—particularly acute in the case of India, the only non-US treaty ally in the group.

Quad 2.0

By the time Japan and the United States floated ideas for reviving the Quad in 2017, the strategic context had changed and the ground for cooperation was much more fertile. Economic and security concerns about China had reached new heights in each country, leading to a convergence of interests and greater willingness to cooperate despite the possibility of drawing Beijing’s ire. The idea of the Indo-Pacific as an integrated theatre had gained traction and was beginning to be translated into policy, first in Canberra and Tokyo, then in New Delhi and Washington. Shinzo Abe had returned to the prime minister’s office in Tokyo in 2012 and again acted as a strong advocate for cooperation between the four countries.7 Bilateral and trilateral cooperation among these countries also started gaining ground, with India’s partnerships with Australia and Japan in particular strengthening considerably.

The revived grouping began meeting regularly at the level of senior officials in 2017. However, it did not issue joint statements, and India did not even use the term Quad in its official statements at the time. Meetings focused on a range of issues including counterterrorism, maritime security, and infrastructure connectivity. But each country issued a different readout, focusing on areas they wanted to highlight. In 2018–2019, Australia was also not invited to join the informal maritime element of the Quad, the Malabar naval exercise including India, Japan, and the United States. Still, despite this fragmentation, the group met regularly, and the Quad foreign ministers convened in 2019 in New York for the first time, indicating that it had forward momentum.

Quad 3.0

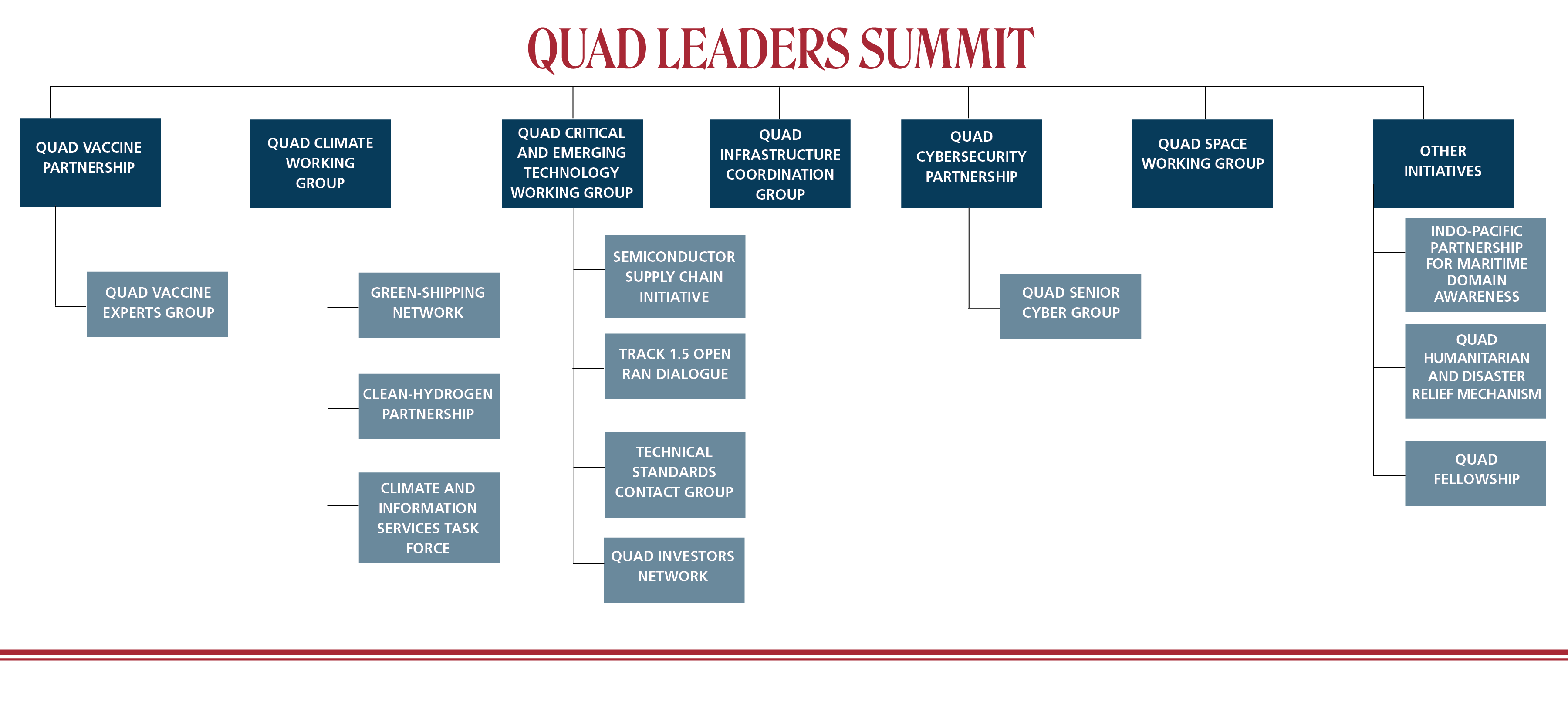

The third step in the evolution of the Quad began with the Biden administration, which elevated the scope and level of ambition of the grouping as well as its institutionalization. The United States hosted the first Quad leaders’ summit in March 2021. This was the first major summit that the Biden administration convened, underlining the importance it placed not only on the Indo-Pacific but on the Quad as a primary vehicle for US policy in the region. The summit was followed by the first joint statement by the Quad. It also “formalized” the Quad by establishing three working groups: on vaccines, climate, and critical and emerging technologies. An additional three working groups were established at the subsequent Quad leaders’ summit in September 2021, focusing on infrastructure coordination, cyber, and space. At present, the institutional structure of the Quad at the leaders’ level consists of the following working groups (see also Figure 1).

The Quad Vaccine Partnership: The original aim of this working group was to produce and deliver one billion doses of COVID-19 vaccines in the Indo-Pacific by the end of 2022, and the Quad countries have collectively provided 257 million doses to the region to date. As the pandemic evolved, so did the goals and mandate of this partnership, including to “prepare for new variants, including by getting vaccines, tests, treatments, and other medical products to those at highest risk.”8 The Biological E. Ltd facility in India is producing vaccines under this partnership. As part of a broad-based pandemic response, it was announced at the Quad leaders’ summit in Tokyo in May 2022 that the Japan Bank for International Cooperation and EXIM India will support a $100 million facility that will bolster India’s healthcare sector, including global capacity for COVID-19 countermeasures.

The Critical and Emerging Technology Working Group: This working group focuses on creating an open, accessible, and secure technology ecosystem. It is organized around four efforts—technical standards, 5G diversification and deployment, horizon scanning, and technology supply chains. Since the working group’s establishment, Quad partners have mapped collective capacities and vulnerabilities in global semiconductor supply chains, launched a common Statement of Principles on Critical Technology Supply Chains, and adopted a Memorandum of Cooperation on 5G supplier diversification and Open RAN. They are also exploring ways to collaborate on open and secure telecommunications technologies in the region, including by working with industry partners.

The Climate Working Group: The Quad countries have expanded and regularized their cooperation on dealing with the climate crisis. The focus of this working group is on green shipping, energy supply chains, disaster risk reduction, and exchange among climate information services. The Quad has also launched a shipping taskforce, inviting leading ports—including Los Angeles, Mumbai Port Trust, Sydney, and Yokohama—to form a network dedicated to greening and decarbonizing the shipping value chain. It aims to establish two or three low-emission or zero-emission shipping corridors by 2030. The working group also convenes meetings of Quad transportation and energy ministers, developing cooperation further.

The Infrastructure Coordination Group: To address the Indo-Pacific’s enormous infrastructure needs, this working group aims to deepen collaboration on digital connectivity, transport infrastructure, clean energy, and climate resilience between the four countries. At the leaders’ summit in May 2022, the heads of the Quad countries’ development-financing agencies met to explore ways to address the infrastructure-financing gap in the region.

The Quad Cybersecurity Partnership: As part of this working group, senior officials from the four countries will meet regularly to build resilience to cyber threats and to advance work between government and industry. The first meeting of this working group took place in March 2022. By the Tokyo summit, the group had defined areas of focus: infrastructure protection (led by Australia), supply-chain resilience (led by India), workforce development and talent (led by Japan), and software security standards (led by the United States).

The Space Working Group: Quad countries are among the world’s scientific leaders, including in space. This working group aims to pool their collective expertise by exchanging satellite data, monitoring and adapting to climate change, mitigating disasters, and responding to challenges in shared domains.

In addition to these working groups, the Quad is also focused on strengthening people-to-people ties between the four countries.

In addition to these working groups, the Quad is also focused on strengthening people-to-people ties between the four countries. The September 2021 summit saw the announcement of the Quad Fellowship, which will sponsor 100 students per year—25 from each country—to pursue degrees at leading science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) graduate universities in the United States. Several private companies have been included as sponsors for this initiative.

At its May 2022 summit in Tokyo, the Quad also launched the Indo-Pacific Partnership for Maritime Domain Awareness, which will offer a near-real-time, integrated, and cost-effective maritime-domain-awareness picture. It will enhance ability of partners in the Pacific Islands, Southeast Asia, and the Indian Ocean to fully monitor their waters. The initiative aims to integrate these three critical regions of the Indo-Pacific and will not only allow tracking of “dark shipping” and other tactical-level activities at sea but also allow countries to respond faster to climate and humanitarian events and protect marine resources and fisheries. And, in a return to the grouping’s roots, the Tokyo summit also saw the creation of the Quad Humanitarian and Disaster Relief Mechanism, through which the four countries will be able to coordinate and mobilize civilian disaster-relief efforts to respond to events in the Indo-Pacific.

Figure 1. Quad Working Groups and Initiatives as of May 2022

- 1Senator Marise Payne, Third Indo-Pacific Oration, September 11, 2021.

- 2Garima Mohan, Assessing the EU’s Indo-Pacific Strategy, London School of Economics, September 24, 2021.

- 3Yoon Suk-yeol, “South Korea Needs to Step Up: The Country’s Next President on His Foreign Policy Vision,” Foreign Affairs, February 8, 2022.

- 4As outlined by one of the participating Australian government officials, Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade: 28/05/2007: Foreign Affairs and Trade Portfolio, Parliament of Australia, May 28, 2007. Abe described his early thinking on cooperation among countries in “broader Asia” in an August 2007 speech to India’s parliament. See Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, Confluence of the Two Seas, August 22, 2007.

- 5Tanvi Madan, “The Rise, Fall and Rebirth of the Quad,” War on the Rocks, November 16, 2017.

- 6For more, see Rory Medcalf, “Chinese Ghost Story,” The Diplomat, February 14, 2008.

- 7Shinzo Abe, “Asia’s Democratic Security Diamond,” Project Syndicate, December 27, 2012.

- 8See “Factsheet Quad Leaders’ Tokyo Summit 2022”, May 23, 2022.

Quad Meetings since 2017

Leaders Summits

- Inaugural virtual summit, March 12, 2021

- First in-person summit hosted by US President Joe Biden, September 24, 2021

- Virtual summit to discuss the conflict in Ukraine, March 4, 2022

- In-person summit hosted by Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida, May 24, 2022

Foreign Ministers Meetings

Foreign ministers exchange views on regional and strategic challenges, and lead a program of cooperation on core regional priorities—including maritime security, countering disinformation, counterterrorism, and humanitarian and disaster relief.

- First meeting in New York, September 26, 2019

- Second meeting in Tokyo, October 6, 2020

- Third meeting, virtual, February 18, 2021

- Fourth meeting in Melbourne, February 11, 2022

Senior Officials Meetings

- Senior officials have held nine meetings since November 2017 to exchange strategic assessments and progress on cooperation

- Quad intelligence chiefs met in September 2021 when they participated in the Quadrilateral Strategic Intelligence Forum

Working Group Meetings

- The six Quad working groups have held meetings led by sherpas and sous-sherpas in each of the four countries.

The Quad has come a long way from its origins, and it has significantly shifted in tone and focus from its early iterations. There are clear signs of deeper integration and formalization, particularly through the creation of its working groups.9 Its agenda has expanded to include economic and nontraditional security issues. The four partners see several advantages to this broad agenda. In addition to countering criticism from China that the Quad is aimed at containing its rise, it also responds to concern from the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) that the Quad is an exclusionary grouping. Overall, it pivots the Quad as a positive force for the Indo-Pacific. As Rory Medcalf puts it, “The new Quad rhetoric is much about spirit and vision, but it is also about defining coexistence with China from a position of strength.”10 Moreover, the general bolstering of ties among the Quad countries across multiple issue areas is an important development that may enable faster, more coherent joint responses to future regional developments.

There are clear signs of deeper integration and formalization, particularly through the creation of its working groups

The Future of the Quad

These recent changes to the Quad raise several questions about its future trajectory:

- What are the drivers of engagement, the domestic support, and the bureaucratic capacity in the four countries to continue investing in the Quad?

- How well does the Quad’s new working-group structure function, and will the working groups be able to deliver tangible results?

- How has the Quad’s agenda evolved, and will it return to its initial focus on security challenges?

- Are the Quad countries open to cooperation with additional countries and, if so, what form will this take?

This section addresses these questions by looking at the domestic discourse around the Quad in the four countries and concludes with key takeaways that point toward the future development of the Quad.

The United States

Elevating the Quad to leader-level meetings and broadening its agenda was one of the early foreign policy successes of the Biden administration. It envisions the Quad as a crucial component in a “latticework of strong and mutually reinforcing coalitions” in the Indo-Pacific.11 The grouping is undergirded in part by the US-led hub-and-spokes alliance system since it includes Australia and Japan. In this sense, the Quad contributes to Washington’s goal of promoting a more “networked security architecture” in which its allies are more strongly tied to one another as well as to the United States.12

From the perspective of key US officials, there is no single desirable institution or forum for dialogue in the Indo-Pacific.

From the perspective of key US officials, there is no single desirable institution or forum for dialogue in the Indo-Pacific. Since each regional institution has limitations, the aim of the Biden administration is to work across different forums in new and innovative ways, letting the agenda guide the choice of forum instead of letting the forum set the agenda. Accordingly, the administration intends to pursue a strategy of flexible “forum shopping” and engagement with a range of different “bespoke or ad hoc bodies focusing on individual problems” to foster regional coalitions.13 As Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin put it in December 2021, such a security architecture “centres on our valued alliances and ASEAN—but it’s reinforced by a range of mechanisms, both old and new, including the Indo-Pacific Quad, and AUKUS, and the Five Eyes, and the triangle of the US, Japan, and South Korea.”14 Consequently, promotion of the Quad is seen by the United States as a way to strengthen the regional security architecture in a manner that is fully complementary to engaging with other existing regional institutions.15

Formalizing the Quad and Challenges

Under the Biden administration, the United States has worked to change the narrative around the Quad, moving away from the Trump administration’s focus on confrontation with China to an approach of working with like-minded countries to deliver public goods and a positive vision for the Indo-Pacific. This was part of an effort to improve the grouping’s reputation in the region by countering the idea of the Quad as an anti-China containment mechanism or as a grouping of large countries that intend to exclude ASEAN and the Pacific Islands. Consequently, the United States is strongly focused on demonstrating that the Quad can deliver concrete and meaningful benefits to the countries of the Indo-Pacific. The US Indo-Pacific Strategy released in February 2022 highlights “deliver on the Quad” as one of the core lines of effort that the Biden administration intends to pursue in the next 12 to 24 months.16

Due to its desire for flexibility, the Biden administration currently has little interest in more formally institutionalizing the Quad in terms of creating a secretariat or adopting a charter. The differentiated, multitrack structure of the Quad is also seen as an advantage, since the leaders’ level can highlight the grouping’s efforts to provide regional public goods while the discussions among foreign ministers or senior officials can tackle more controversial security issues. However, US officials recognize that the difference in bandwidth among the four countries means that the Quad’s flexible, weakly institutionalized structure creates challenges when it comes to operationalization and implementation. Due to differences in domestic bureaucratic structures across the four countries, US working-group leads do not always have counterparts with comparable resources or staffing. When it comes to institutionalizing the Quad, however, the most immediate US aim is to regularize meetings of leaders, ministers, senior officials, and working groups to give the grouping enough structure to move forward on its agenda.

When it comes to institutionalizing the Quad, however, the most immediate US aim is to regularize meetings of leaders, ministers, senior officials, and working groups to give the grouping enough structure to move forward on its agenda.

Similarly, there is also little US interest in formally expanding the Quad to include additional member countries. There may, however, be opportunities for partner countries to engage with Quad working groups. For example, US National Security Council Director for the Indo-Pacific Mira Rapp-Hooper has stated that the Quad would like to have the ability to invite other partners on an informal basis, particularly in the critical and emerging technology space, and that the other three countries would also welcome being invited to a meeting of the EU-US Trade and Technology Council.17 However, some US officials interviewed expressed reservations about cooperation with additional partners through Quad working groups, suggesting that this is only likely to happen if there are clear benefits to doing so and that such cooperation may be limited to a specific goal or time period. This reflects the ongoing prioritization of solidifying ties within the Quad over broadening the coalition.

Overall, US officials express confidence about the future of the Quad, regardless of any future changes in US leadership. They point out that much of the grouping’s activity occurred during the Trump administration prior to the leaders’ summits during the Biden administration. An additional benefit of the creation of the working groups has been the engagement of a wide range of departments and agencies in Quad activities, which has broadened buy-in beyond the National Security Council and the State Department. To further guarantee investment in the Quad, US officials are considering incorporating additional layers of people-to-people connections. For example, there is interest in initiating parliamentary engagement among Quad countries, as well as starting a Track 1.5 dialogue at the policy-planning level to further substantiate its activities.

In terms of the Quad agenda, given the devastating impacts of the coronavirus pandemic on the Indo-Pacific, health cooperation has so far been the highest priority for regional deliverables from the US perspective. Up to this point in time, there has been an intense focus on the vaccine partnership in Washington. After vaccines, US officials hope to move beyond coronavirus-specific measures and expand to broader issues of pandemic readiness. They also see clean hydrogen and green shipping as having potential. With regard to the regional dimension, the United States intends to significantly step up its engagement in the Pacific Islands in the years ahead as part of its Indo-Pacific strategy. The top concerns of these countries are the existential challenges posed by climate change and the pandemic, which fits very well with the remit of the Quad. The war in Ukraine has also highlighted the potential for the Quad countries to jointly respond to and comment on global events outside the region—as demonstrated by the Quad virtual summit in March 2021—which is something that the United States hopes to continue in the future.

India

Over the last two years, as challenges emanating from China have increased, India has intensified its engagement with the Quad, which in turn has propelled the development of the grouping. The country has often been referred to as the Quad’s weakest link, but that description is not entirely accurate and is strongly refuted by policymakers in New Delhi. Instead, experts characterize India as the Quad’s, in Tanvi Madan’s words, “pacing partner.”18 Since the other Quad countries are US allies with significantly deeper defense and security ties with each other, it was only natural that India would occupy a different position. However, India’s level of buy-in has steadily increased, especially as its relations with China have worsened. Minister of External Affairs Subrahmanyam Jaishankar recently characterized the “firm establishment of the Quad” as “major diplomatic accomplishment” of the government of Prime Minister Narendra Modi.19 “India has driven the rejuvenation of the Quad in the last three years,” remarked a senior government official at the 2022 Raisina Dialogue.20 The White House has also called India the “driving force of the Quad.”21

India has also been active in shaping the Quad’s broadening agenda along with the United States, specifically in adjusting the grouping’s framing and portraying it as a solution provider for the region.

Three drivers explain India’s increasing interest in the Quad. The most important is signalling to China. Violent border clashes with China have accelerated the reorientation of Indian foreign policy toward deeper engagement with the West, particularly toward the Quad. Second, the Quad also contributes to India’s broader foreign policy objectives in the Indo-Pacific. “From an Indian perspective, it is also a statement of [India’s] growing interests beyond the Indian Ocean”, Jaishankar has said.22 The Quad links neatly with the country’s aim to being a net security provider in the Indian Ocean, and its focus on delivering public goods contributes to Indian policies like Act East by increasing engagement with Southeast Asia and the Pacific Islands. Finally, being a part of the Quad also helps India build its capacities.

India has also been active in shaping the Quad’s broadening agenda along with the United States, specifically in adjusting the grouping’s framing and portraying it as a solution provider for the region. India has been particularly sensitive that the grouping should not be seen as an anti-China coalition, and it is also mindful of the criticism of the Quad coming from its partners like Russia and ASEAN. For this reason, its Indo-Pacific vision stresses being “inclusive”.

Formalizing the Quad and Challenges

These drivers, along with the formalization of the Quad through the creation of the working groups and appointment of new Quad counterparts in a wider range of ministries beyond the Ministry of External Affairs, have led India to be more invested in the grouping. For instance, bodies like the National Security Council Secretariat have taken the lead on critical technology issues. Engagement with the grouping is not as ad hoc as it was in the past and many in India argue this would withstand any change of policy; for instance, due to improvement in India-China ties.

However, formalization also creates a few impediments to cooperation for India. The number of working groups and issues on the table require a significant amount of bureaucratic capacity, which would be challenging for most countries but is particularly acute for India, which has a much smaller foreign policy bureaucracy and suffers from capacity constraints. Another potential obstacle relates to India’s assessment of the other partners’ commitment to the Quad and their positioning vis-à-vis China. “If India perceives that the enthusiasm for the grouping is waning in Australia, Japan, or the United States, then it could recalibrate or downgrade its involvement.”23 Other developments in the region could also impact India’s assessment. For instance, when the Australia-United Kingdom-United States (AUKUS) partnership was announced in 2021, there were questions in India as to whether this would complement the Quad or undercut it. These questions have now largely dissipated but they could arise again with similar developments in the future.

The absence of an explicit condemnation by India of Russia’s actions, particularly in the early days of the conflict, raised questions about the implications for the Quad.

The biggest challenge to Quad unity has come with Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. The absence of an explicit condemnation by India of Russia’s actions, particularly in the early days of the conflict, raised questions about the implications for the Quad. The virtual leaders’ summit that was called to discuss the war in Ukraine highlighted these differences. In the statements following it, India seemed to reiterate its preference that the Quad should address challenges in the Indo-Pacific, whereas the war had broader implications for the other three partners.24 Some policymakers interviewed argued that the summit was useful in sharing assessment of facts on the ground and underlined that the four partners were on the same page in their understanding of Russia’s actions. As the war has progressed and civilian casualties have increased, India’s position has evolved and the gap between its position and those of the other Quad partners has narrowed.

However, it remains to be seen what the long-term impact of this divergence might be, if any. It will be difficult for the other three countries to explain India’s “like-mindedness” to their domestic constituencies. On the other hand, the US-India 2+2 meetings at the level of defense and foreign ministers, the recent signature of the India-Australia interim Economic Cooperation and Trade Agreement, progress on several goals, and activities under the Quad seems to suggest the Ukraine war has not yet seriously impacted other partners’ assessment of and enthusiasm for India as a partner.

Australia

The Quad is a “key pillar” of Australian foreign policy’s Indo-Pacific agenda.25 It complements other bilateral, regional, and multilateral engagements the country has in the region. Australian policymakers view the Quad as an innovative, flexible, and creative mechanism that focuses on practical issues in the Indo-Pacific. The agility it affords is appreciated in policymaking circles. Experts interviewed said that the Biden administration has hit the ground running on the Quad, specifically through the creation of the working groups. These early efforts to embed the Quad in a broader, non-confrontational agenda are seen as a positive development in Canberra. US investment in the Quad is also a signal of leadership from Washington. The experts also argued that the Quad has “made the region safer for trilaterals” and that its non-military agenda is ideal for responding to ASEAN’s concerns about the grouping.

One crucial question is how Australia’s new Labour Party government will respond to the Quad and the country’s role in it. In an important signal, Prime Minister Anthony Albanese and Foreign Minister Penny Wong travelled to Tokyo to attend the Quad Leaders’ Summit 72 hours after the elections concluded. At the meeting, Australia also proposed to hold the next leaders’ summit in 2023.

While there might be different degrees of enthusiasm, others contend, the Labour Party is broadly on board with the Quad and the Indo-Pacific agenda.

Many experts say that there is broad, bipartisan support for the Quad in all its forms, along with support for participation in the Malabar exercise and AUKUS. Former Australian leaders have often penned articles critical of the country’s participation in these activities, but the political establishment agrees on the utility of these platforms. While there might be different degrees of enthusiasm, others contend, the Labour Party is broadly on board with the Quad and the Indo-Pacific agenda. When Australia hosted the Quad foreign ministers meeting in February, US Secretary of State Antony Blinken, India’s Minister of External Affairs Subrahmanyam Jaishankar and Japan’s Minister of Foreign Affairs Hayashi Yoshimasa met with the then opposition senator Wong. Wong tweeted at the time that their talks had reaffirmed “our strong ties, including through the Quad.”26 She later delivered a strong message of support for the Quad and strengthening Australia-India ties at the Raisina Dialogue in April 2022.

Formalizing the Quad and Challenges

Australia sees itself as a leader in pushing for deepening Quad cooperation in creative ways, as part of its “long tradition of building coalitions”. The Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade has a specific section dedicated to the Quad; however, it does not lead on all the working groups. For example, the Department of Home Affairs leads on the working groups on cyber and on critical and emerging technologies. This requires a level of inter-agency coordination, which can also be challenging at times. Australia has also appointed a sherpa for refining the Quad agenda, leading on implementation, and thinking of new and creative ways of cooperation that can leverage the flexibility afforded by this grouping.

As the next steps, policymakers in Australia say the working groups need to identify and implement concrete projects. Beyond navigating bureaucratic politics in each country, they identify delivery as the most important challenge for the Quad. Those interviewed recognize that the working groups are still at an early stage although a great deal of detailed work has been done in crafting their agendas. Another potential challenge could be eventual shifts in the policy priorities of the four countries, which might focus on some areas more than others.

There is some reluctance in Australia about expanding the membership of the Quad. However, interviewed experts state that there can be functional activities within the working groups that could be “Quad plus,” and incorporate other countries or organizations as necessary.

Many interviewees said the “values versus interests” debate will be crucial and the fact that the Quad partners are not like-minded on every issue could be raised by its critics in Australia and abroad. This will be something the grouping has to contend with. Many also mentioned that India’s positioning on Ukraine has raised question among policymakers and the public in the other Quad countries, which are not familiar with traditions of Indian diplomacy. There will need to be some expectation management when it comes to that. The Quad will also have to manage expectations—both in the four countries and in the region—on meeting hard-security challenges, especially as its agenda has broadened considerably. And finally, for the Quad’s long-term survival and utility, it will have to marshal structures and processes for delivery.

Japan

The Quad plays the central role in a set of multilayered initiatives through which Japan aims to realize its Free and Open Indo-Pacific (FOIP) vision.27 For Japan, the FOIP has evolved from a strategy more explicitly focused on security concerns related to China to a more inclusive vision that embraces non-security issues and is not explicitly aimed at any one state. This evolution also mirrors the changes in the Quad. The pillars of Japan’s FOIP vision are promoting and establishing fundamental principles such as the rule of law, pursuing economic prosperity, and ensuring peace and stability.28 Japan welcomed the US efforts to elevate the Quad to the leaders level, and Japanese officials interviewed say that the grouping has also helped to upgrade the position of Australia, India, and Japan in regional cooperation.

Abe’s two successors have maintained a consistent focus on the Quad as a key part of Japan’s commitment to the region.

Given the importance of former prime minister Shinzo Abe in the original formulation of the Quad and its revival in 2017, some observers speculated that his departure from office in 2020 might weaken Japan’s commitment to the grouping. However, Abe’s two successors have maintained a consistent focus on the Quad as a key part of Japan’s commitment to the region. Both held key positions in the Abe administration. Yoshihide Suga, who took office in 2020, was Abe’s chief cabinet secretary for eight years and maintained strong continuity with his foreign policy as prime minister, including emphasis on the Quad. When Fumio Kishida became prime minister in July 2021, his reputation as a friend of China and a dove led some to believe that he might weaken Japan’s support for the Quad. However, Kishida, who was foreign minister under Abe, has also maintained a strong focus on the grouping.

Formalizing the Quad and Challenges

Japanese policymakers are highly concerned about solidifying the Quad. Officials interviewed expressed a desire to strengthen the relationships between the four countries to ensure that differences between them do not overshadow their shared interests and that no single country can be pulled away from the grouping by China. Accordingly, Japan’s government has strengthened bilateral relationships with the other partners, particularly India, which it has tried to encourage to be more strongly committed to the Quad.29 The war in Ukraine has added another dimension to these concerns; several Japanese officials interviewed described keeping India on board as their primary goal within the Quad at the moment.

In line with this emphasis on bolstering ties among the four countries, there is little Japanese interest in formally expanding Quad membership or pursuing expanded cooperation with additional countries at this time. Government officials do not see a need to further institutionalize the Quad through the formation of a secretariat and argue that the current working-group structure is sufficient for the grouping’s goals. They also point out that the regularizing of meetings has already happened on a de facto basis, which indicates that the Quad is able to maintain consistency without additional formal structure.

Japan is determined to demonstrate the Quad’s ability to deliver meaningful benefits and public goods to the Indo-Pacific region.

Japan is determined to demonstrate the Quad’s ability to deliver meaningful benefits and public goods to the Indo-Pacific region. The government wants to capitalize on the recent momentum, and officials fear that the grouping will falter if the current opportunity is not seized. In the short term, the coronavirus pandemic presents an opportunity to deliver on a pressing need to provide vaccines and other support to the region. Beyond vaccines, Japanese officials see infrastructure investment as an important priority on the Quad’s agenda, and Japan’s considerable resources and history of regional cooperation on infrastructure will be necessary to achieve the grouping’s goals. Some Japanese officials interviewed also expressed a desire for more cooperation on traditional security issues within the Quad, describing the new Indo-Pacific Partnership for Maritime Domain Awareness as an important step in this direction that will create a foundation for cooperation, including joint training and analysis.

Japanese leaders are likely to remain strongly committed to the Quad in the future. The governing Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) is acutely aware of the multidimensional challenge posed by the rise of China. While its alliance with the United States remains the foundation of Japan’s security policy, the Quad is a natural extension of Japan’s desire to build a strong coalition of like-minded democracies to reinforce the rules-based order against shared threats. These structural factors mean that Japan is likely to continue to strongly support the Quad as a key element of its approach to regional security architecture. The government also sees the Quad as a way to bolster the international order beyond the Indo-Pacific, and it has advocated using the grouping to push back against Russia’s aggression against Ukraine. Support for the Quad is robust across the electorally dominant LDP, making it unlikely that Japan will dramatically change its basic policy orientation toward the Quad. However, there may be some questions about the intensity with which Japan can pursue goals within the Quad if its government becomes more focused on domestic concerns or if more frequent changes in leadership weaken its ability to devote sustained attention to foreign policy initiatives.

Conclusion

The Quad has come a long way from its original incarnation. Its rapid institutional development since its revival in 2017 has catalyzed a wave of cooperation between Australia, India, Japan, and the United States. The Quad has tried to preserve the flexibility of a loose coalition and aims to be faster and more delivery-oriented than established regional organizations. At the same time, however, the grouping is very much a work in progress. This paper offers the following takeaways about the Quad after the developments of the past several years.

- 9For a detailed readout of the Quad working groups, see Fact Sheet: Quad Leaders’ Summit, September 24, 2021.

- 10Rory Medcalf, The Quad has seen off the sceptics and it’s here to stay, National Security College, Australian National University, March 16, 2021.

- 11White House, Indo-Pacific Strategy of the United States, February 2022.

- 12Richard Fontaine et al., Networking Asian Security: An Integrated Approach to Order in the Pacific, Center for New American Studies, June 2017.

- 13This strategy was previewed in Kurt Campbell and Rush Doshi, “How America Can Shore Up Asian Order: A Strategy for Restoring Balance and Legitimacy,” Foreign Affairs, January 12, 2021.

- 14US Department of Defense, Remarks by Secretary of Defense Lloyd J. Austin III at the Regan National Defense Forum (As Delivered), December 4, 2021.

- 15White House, Background Press Call by Senior Administration Officials Previewing the Quad Leaders’ Summit and Bilateral Meeting with India, September 24, 2021.

- 16White House, Indo-Pacific Strategy of the United States, February 2022.

- 17Mira Rapp-Hooper, comments at event on “US-Europe Cooperation in the Indo-Pacific,” The German Marshall Fund of the United States, February 28, 2022.

- 18Tanvi Madan, “India and the Quad”, in Asia-Pacific Regional Security Assessment 2022, International Institute of Security Studies

- 19Subrahmanyam Jaishankar, “Quad validates PM’s India-first approach,” The Hindustan Times, May 25, 2022.

- 20See remarks by Ashok Malik from the Ministry of External Affairs India on “The Rejuvenation of the Quad has been Primarily Driven by India. Washington has Played Catch-up” at the Raisina Dialogue session on “Domestic discord, global expectations: will the American Eagle Fly?”, April 27, 2022.

- 21The Hindu, “India is the driving force of the Quad,” February 15, 2022.

- 22Jaishankar, “Quad validates PM’s India-first approach.”

- 23Madan, “India and the Quad.”

- 24The Prime Minister’s Office in India stated that “the Quad must remain focused on its core objective of promoting peace, stability and prosperity in the Indo-Pacific region.” See Shubhajit Roy, “Divided over Russia, Quad on the same page: channel for relief over Ukraine,” The Indian Express, May 13, 2022.

- 25Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, Brief on the Quad,

- 26Senator Penny Wong, “The US, India and Japan are great friends of Australia - as well as vital strategic partners in our region. @AlboMP and I had constructive talks with @SecBlinken @DrSJaishankar and Minister Hayashi - reaffirming our commitment to stronger ties, including through the Quad.” Twitter, February 10, 2022.

- 27Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, Press Conference by Foreign Minister Hayashi Yoshimasa, April 12, 2022.

- 28Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, Free and Open Indo-Pacific, March 3, 2022; Ministry of Defense of Japan, Free and Open Indo-Pacific: Japan’s Ministry of Defense’s Approach, September 27, 2021.

- 29PTI, Want India to ‘commit more’ to Quad: Japanese Deputy Defence Minister, The Week, December 25, 2020.

Takeaways about the Quad

Expand AllFlexibility with Limited Formalization

There is little interest in institutionalizing the Quad by establishing a secretariat or adopting a charter. All four partners consider the flexible nature of the grouping to be an asset. However, the Quad is undergoing a degree of deeper integration and formalization, especially through the creation of its working groups and the appointments of sherpas in each country. An immediate goal is to regularize meetings of the Quad leaders, ministers, senior officials, and working groups to give the grouping enough structure to move forward on its agenda, though this regularization already seems to be happening naturally to some extent.

Broadened Support within the Quad Countries

The working-group structure and the range of issues covered has ensured that the constituency of supporters and those involved with the Quad has grown beyond security policy circles in the four countries. The working groups have also entrenched the Quad more firmly in policymaking institutions within each country, and there is clear support for it across the political spectrum in all of them. However, some caution that this broad-based political support could be impacted if the policy priorities of one of the partners changes.

Challenges of Delivery

The Quad’s long-term survival and utility will depend on its ability to marshal its structures and processes for delivery. Officials in the four countries seem generally confident that the flexibility and informality of the grouping will be an asset in this regard. However, the Quad’s weakly institutionalized structure also creates challenges when it comes to operationalization and implementation. The four countries have different levels of bureaucratic capacity and bandwidth. Working-group leads do not always have counterparts in other countries with comparable resources or staffing.

No Expansion of Membership

The focus of the Quad countries currently is on internal coordination and delivery. Officials emphasize that they are not interested in formally expanding the grouping or in creating specific institutional structures involving additional partners at this time. Rather, they recognize there is still work to be done in aligning the approaches of the four member countries across the grouping’s growing agenda. Moreover, despite the changing narrative of the Quad as a provider of public goods to the Indo-Pacific, the four countries are still motivated by their shared alignment on their assessment of the threats and challenges posed by China. Not all potential partners share this assessment and some might be more comfortable coordinating with the Quad behind the scenes.

Flexible and Functional Cooperation with Additional Countries

Instead of expanding the Quad’s membership, the four countries may be open to functional cooperation with additional countries on a limited basis in the future. Additional partners can be flexibly incorporated in functional initiatives and projects within working groups, if it makes sense from the Quad members’ perspectives. Such collaboration might span only the time necessary to achieve a shared goal on a specific issue. It will be beneficial for the Quad countries to attempt to harmonize their discussions with others, particularly in situations where similar ones are occurring in other regional or international forums.

Expanded Agenda with Continued Security Cooperation

Despite the expansion of the Quad agenda to include economic and nontraditional security issues, traditional security cooperation remains a key pillar of the grouping. The recently announced Indo-Pacific Partnership on Maritime Domain Awareness has important security implications. Moreover, while most public attention has focused on the six leader-level working groups addressing economic and nontraditional security challenges, cooperation on security issues such as maritime security as well as on cybersecurity, counterterrorism, countering disinformation, and humanitarian assistance and disaster response have continued at the ministerial or working level. Ministerial meetings have a lower profile; for example, and the Quad foreign ministers have only released one joint statement from their meetings so far.30 The four countries also continue to deepen their security cooperation bilaterally and trilaterally in important ways. Thus, its multilayered and flexible structure enables the Quad to serve multiple purposes at once and to elevate the visibility of noncontroversial issues while continuing important discussions on more sensitive security concerns below the surface.

- 30US Department of State, “Joint Statement on Quad Participation in the Indo-Pacific, February 11, 2022.

Increasing Strategic Alignment

The Quad partners have also increased their alignment on strategic issues, as demonstrated by their issuing joint statements and gradually deepening their cooperation. Its member countries see the Quad as a grouping that can be quickly convened to coordinate responses to international events, suggesting that it has a relevance beyond its regional agenda. This was demonstrated when the Quad leaders met virtually in March 2022 to discuss Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. After that meeting, US National Security Council Senior Director for East Asia and Oceania Edgard Kagan observed that the Quad is “a mechanism that leaders use to coordinate in response to events and to emerging situations, as well as to make sure that we remain coordinated in our approach to how we work in the Indo-Pacific.”31 If this type of coordination is enhanced, the Quad may also enable the four countries to align their positions before proceeding to discussions in larger forums such as the United Nations or the World Trade Organization, which could serve as a foundation for partnering with additional countries on shared goals

31. Nirmal Ghosh, “Quad summit signals the US is not taking its eye off the Indo-Pacific,” The Straits Times, March 4, 2022.

Whether the Quad will be able to circumvent challenges that come with the combination of an expanding agenda and limited formalization remains to be seen. There is no doubt there will be constraints on what the four countries can do together, and the ability of the Quad to maintain its impressive momentum will depend on the ability of its members to solidify their ties and increase their alignment. The four countries are acutely aware of this, as demonstrated by their current intense focus on matters internal to the grouping.

Externally, a major challenge for the Quad will be to manage expectations and to follow through on its pledge to work inclusively with other countries—particularly in Southeast Asia and the Pacific Islands but also more broadly. The rapid development of the grouping has generated a tremendous amount of interest among potential partner countries inside and outside the region. The expansion of the focus of the Quad beyond the maritime domain and security questions also creates more room for potential partners. The agenda now outlined by the Quad countries falls neatly in line with the Indo-Pacific priorities of many other countries, including in Europe. The Quad leaders have clearly signalled their desire for the Quad to be a flexible coalition, which suggests that it will be ready to work with others on an issue by issue basis in the future, even if there is currently hesitation about doing so.

The Quad leaders have clearly signalled their desire for the Quad to be a flexible coalition, which suggests that it will be ready to work with others on an issue by issue basis in the future, even if there is currently hesitation about doing so.

From the broader perspective of the emerging institutional architecture of the Indo-Pacific, some drawbacks of promoting the Quad as one part of a patchwork of minilaterals have already been identified. For example, the proliferation of similar initiatives has the potential to create problems of policy harmonization. Now that some European countries also have Indo-Pacific strategies and are investing resources into similar policy areas as the Quad, there is a pressing need for coordination, so that they and the Quad partners do not end up duplicating or worse undercutting each other’s efforts in the region. Some have also expressed concern that ad hoc minilateral efforts will weaken more established organizations, such as ASEAN. As time goes on, these questions of broader regional institutional architecture will become more pronounced, and the ability of the Quad to link its efforts to broader regional and international initiatives will determine the reach of the grouping’s impact. For the moment, however, the Quad is a grouping on the rise, and it appears poised to grow still more influential in the future if its members can balance the internal and external challenges that lie ahead.

Quad Plus in Europe and Asia

GMF’s Quad Plus research explores opportunities for cooperation between Quad countries and partners in Europe and Asia.

Acknowledgments

This paper was made possible by a grant from Policy Planning of the Federal Foreign Office of Germany.