Germany's Political Center is Stronger Than it Looks

Photo by: Jürgen Matern

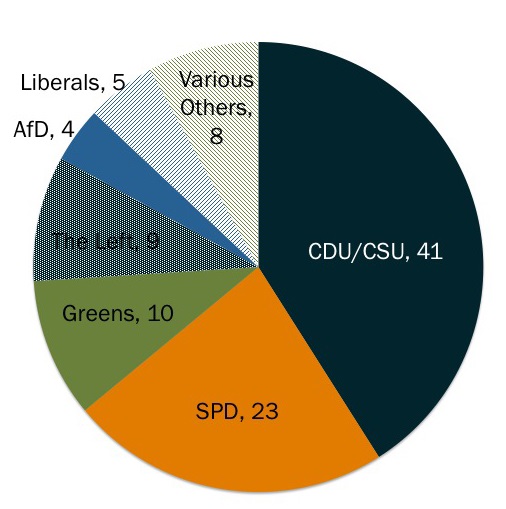

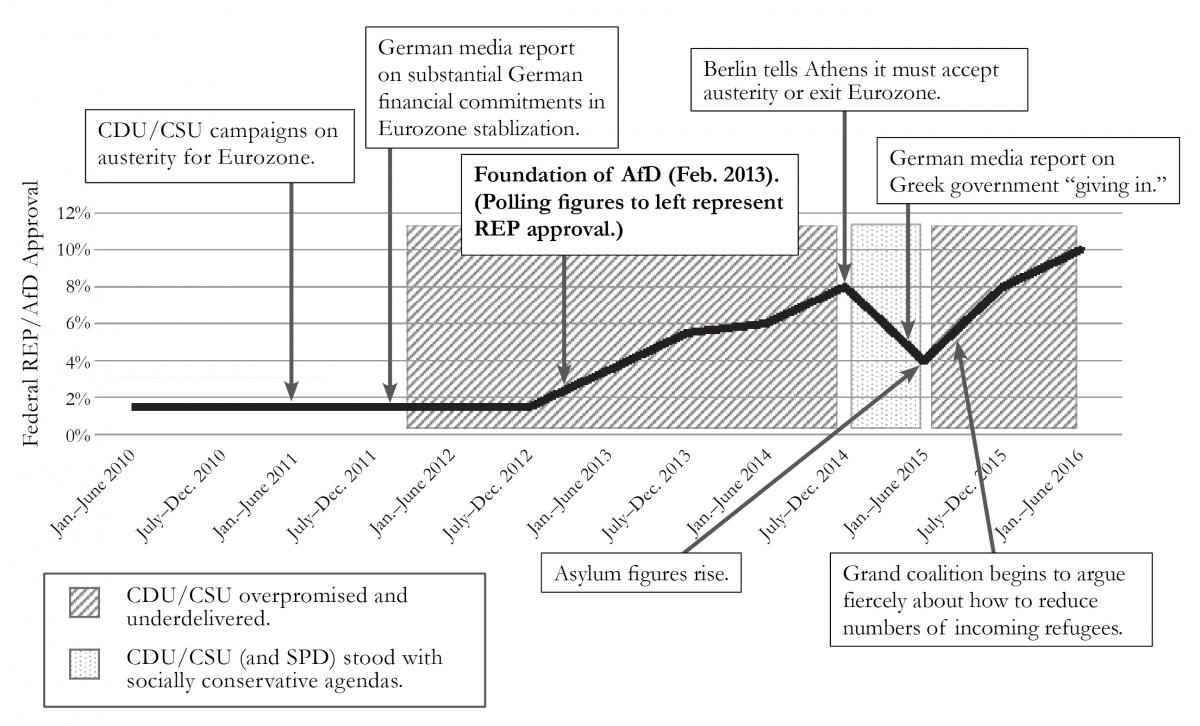

Across Europe and even in the United States, centrist parties and politicians are being challenged by right-wing (and in some cases left-wing) populists who are contesting long-standing pillars of their countries’ politics, including membership in the European Union. In France, the anti-immigration, anti-EU Front National has been a major political force since the 1980s, and Britain’s anti-EU United Kingdom Independence Party has successfully pushed the U.K. out of the EU, with not as yet known consequences. In the Netherlands and Scandinavia, right-wing populist parties have been consistently polling at around 20% for more than a decade in many cases. Germany, in contrast, seemed a stronghold of political stability. In the summer of 2015, Germany’s ruling conservative Christian Democrat/Christian Socialist Party (CDU/CSU[1]) was polling at above 40% support, while the right-wing, anti-European Alternative für Deutschland (AfD), which emerged on the scene in 2013, was polling at a meager 4% (Figure 1a).

One year and about 1.5 million refugees later, German voters have grown frustrated with the governing parties, and the AfD is reaping most of the benefits. Now support for German political parties has become more dispersed, with the AfD clearly making the biggest gains: CDU/CSU 33%, Social Democrats (SPD) 21%, Greens 13%, and AfD 11-13% (Figure 1).[2]

Given Berlin’s central role in the European Union and its growing role in global policy, it is hard to imagine the EU navigating the major crises it continues to face without a politically stable – and pro-European – Germany. However, rapidly rising support for right-wing populism looks to be following a European trend, which has many commentators worried and even predicting Chancellor Angela Merkel’s imminent fall. There is certainly reason for Germany’s mainstream parties to be concerned and take action, but they have survived worse and seem to have learned important lessons. If Germany’s centrist parties are able to agree on conservative integration policies and communicate these to the voters far more effectively in late 2016 than they did in the first half of the year, and engage in a passionate debate over economics throughout 2017, they can regain voters before the elections in 2017.

It is the Debates, More than the Numbers

The immense influx of asylum seekers is generally seen as the source for AfD’s recent success, as voters reject increased immigration per se. But it is a bit more complicated than that. AfD’s large gains were aided by the fierce debate among the parties in the governing coalition (the conservative CDU, its Bavarian sister party CSU, and the SPD) that erupted in the autumn of 2015 about how to lower the numbers of refugees arriving in Germany. In June 2015, Germany took in about 40,000 newcomers. In July, it was 80,000; in August and September 270,000; and another 550,000 came during the months of October, November, and December. Reacting to these staggering numbers, Merkel and the CDU wanted a “European solution,” meaning a strengthening of EU border controls and a European quota system for the distribution of refugees entering the EU. The CSU, however, called for reintroduction of massive German border controls to prevent refugees from entering the country. The SPD was torn between both, supporting Merkel’s European approach at first, but key figures within the party soon started calling for a cap on the number of refugees (as such, indirectly supporting the national solution of the CSU).

Dissatisfied with these disagreements among the governing parties, German voters turned to the right-wing populist AfD in much greater numbers from autumn 2015 onwards. Comparative research shows that right-wing populist parties in Western Europe gain support if established parties introduce conservative positions in a heated debate and then back away from these positions. This disappoints conservatives who have been mobilized on that very issue, and they then look for a new political home.[3] The quick ascent of UKIP in the U.K., for instance, is a result of Prime Minister David Cameron’s flip-flopping over EU membership, while populists in the Netherlands benefited from Prime Minister Mark Rutte not sticking to his conservative pledges in European politics, namely announcing a clear-cut austerity line against Greece and the supporting the bail-outs. In all three cases, center-right parties overpromised on conservative agendas and failed to deliver sufficiently. This opened the electoral niche for a right-wing populist challenger that could tap into the disappointment of previously mobilized conservative voters.

It is not so much the real immigration figures that matter, but the parties’ communication about the numbers and policies.

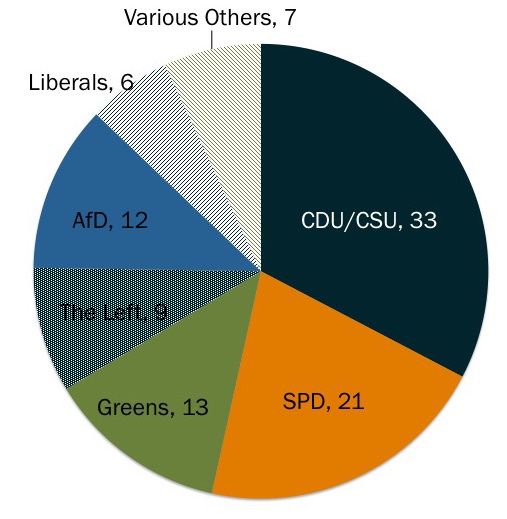

This same pattern was visible around the issue of border controls. The CSU was calling for the national borders to be closed, thus legitimizing these positions, but could not push the government to follow these demands. This meant a conservative position was established, but no federal actor acted on it. This opened the niche for a right-wing challenge. The AfD rose from 4% to as much as 13% support in the polls in a matter of four months.

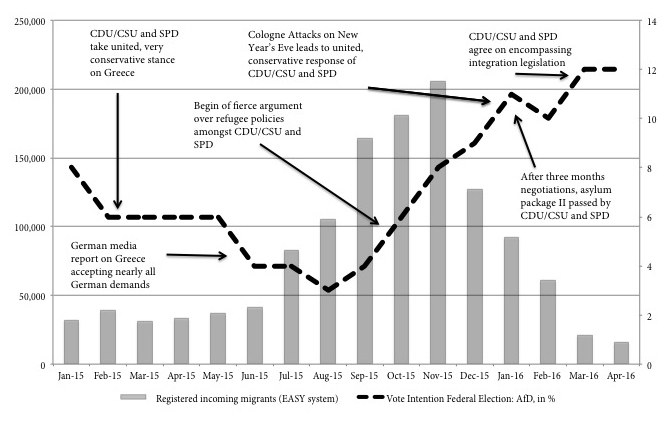

It is not so much the real immigration figures that matter, but the parties’ communication about the numbers. The increasing numbers of refugees correspond exactly with rising AfD figures only once – in the autumn of 2015. However, in January 2015, the AfD was polling at 8% without a large number of refugees arriving, and though the arrivals have remained at the new lower numbers since February 2016, the AfD continues to poll at 13%. Thus, though there is a correlation between more refugees and rising AfD polling in the autumn of 2015, the numbers of arrivals and the AfD poll numbers do not track one-to-one. However, the increasing numbers over the autumn of 2015 led to a change in party political public discourse. These communication patterns of Germany’s governing parties are a closer match with the fluctuations in AfD polling. When the coalition communicated a united conservative position on matters concerning German national identity, the AfD has lost support or remained stable (e.g. during the debates on Greece in the first half of 2015 and after the agreements on integration legislation in February 2016 and onwards). When Germany’s two centrist parties disagree fiercely on matters concerning German national identity, voters turn to the AfD (as seen with the debate about rising refugee numbers in winter 2015/2016). As Figure 2 illustrates, AfD polling numbers track close to these mainstream party debates, which is in line with broader research on messaging and populist parties.[4]

Conflict between and in the governing parties allows a new political challenger to argue that the governing parties have lost control over German borders. And after the CSU called for national borders to be closed, but the CDU and the SPD prevented it from happening, the AfD could point out that an “orderly approach” was available, but the “establishment” was ignoring it. Had the CDU agreed to the CSU’s prominent demands for border controls, conservative voters would have stuck with the CDU/CSU. They did not, and the AfD used its anti-establishment rhetoric and conservative law-and-order demands against the CDU/CSU and the SPD alike.

Incoming refugees are no longer an acute problem, but that does not mean the sailing is clear. Since the beginning of 2016, the number of incoming refugees to Germany has dropped sharply, which has “solved,”

at least temporarily, one problem for the governing coalition. This is crucial, since a reduction in arrivals is one of the few clear promises Merkel made to voters. In November, 206,000 incoming refugees were registered; in January there were only 92,000, and in both April and May of 2016 each, only 16,000 asylum seekers were registered. For the domestic debate, it is irrelevant whether this is a result of the closing of the Balkan Route or the EU refugee deal struck with Turkey;[5] German politicians can claim responsibility for the reduction of incomings to Germany – and need not debate the issue further.

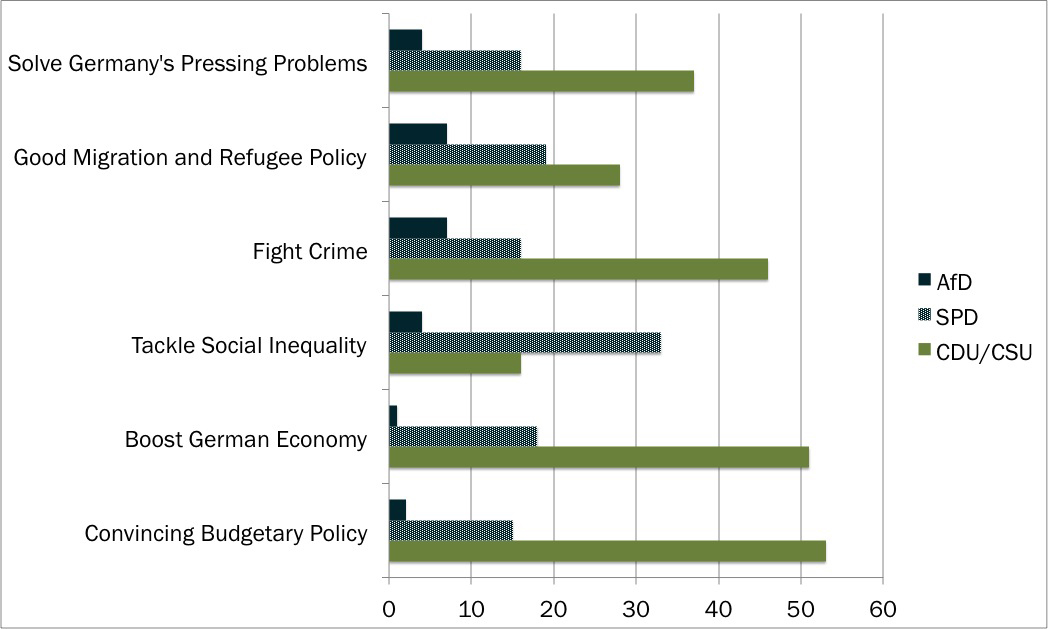

Worries over massive numbers of incoming refugees has now been replaced by concerns about integrating those who arrived last year. The public mood has thus lightened a bit, but integration issues are still a prime concern of German voters (Figure 3). In the eyes of these voters, mainstream parties have not yet formulated a common approach on integration issues and a clear-cut conservative agenda on immigration and integration seems to be missing. As a result, the AfD can still present itself as the only “true conservative force” in German politics – and immigration will remain a central issue. This is to the advantage of populist parties, and hurts mainstream parties on either side. Consequently, positioning and messaging on migration and integration policy in the next

months will be decisive for the electoral fortunes of the governing parties as well as the AfD in 2017.

The Roots of AfD’s Success – and its Weaknesses

The remarkable electoral success of the AfD in the regional elections in March in Saxony-Anhalt (24.2%), Baden-Württemberg (15.1%) and Rhineland-Palatinate (12.6%) and in September in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern (20.8%) and Berlin (14.2%) resulted from a three-fold programmatic niche the AfD could fill: migration, protest, and an economic-conservative alternative.

As discussed above, the AfD offered a clear, conservative migration policy that would quickly reduce the number of incoming refugees (the AfD argued for introducing border controls within the Schengen area). In doing so, it was the only party offering a “quick fix” to the immigration challenge, as the mainstream conservative parties were torn between the discussed European solution (CDU) and the reintroduction of border controls (CSU).

The AfD also provided an outlet for a democratic protest vote against alleged elitism in Berlin. The grand coalition between the CDU-CSU-SPD rather swiftly reached compromises on fiscal and welfare state policies over the last years. This absence of robust debate in the center, can be used by populists to suggest they provide the only alternative vision. In addition, there did not seem to be any viable alternatives to Merkel as chancellor. Voters want unity on issues concerning national identity, and they want the government to be in control of potentially destabilizing situations. But if there seems to be too much consensus on other issues, especially socio-economic issues, mainstream governing partiescan be portrayed as protecting the status quo instead of competing for the best policies for the country.

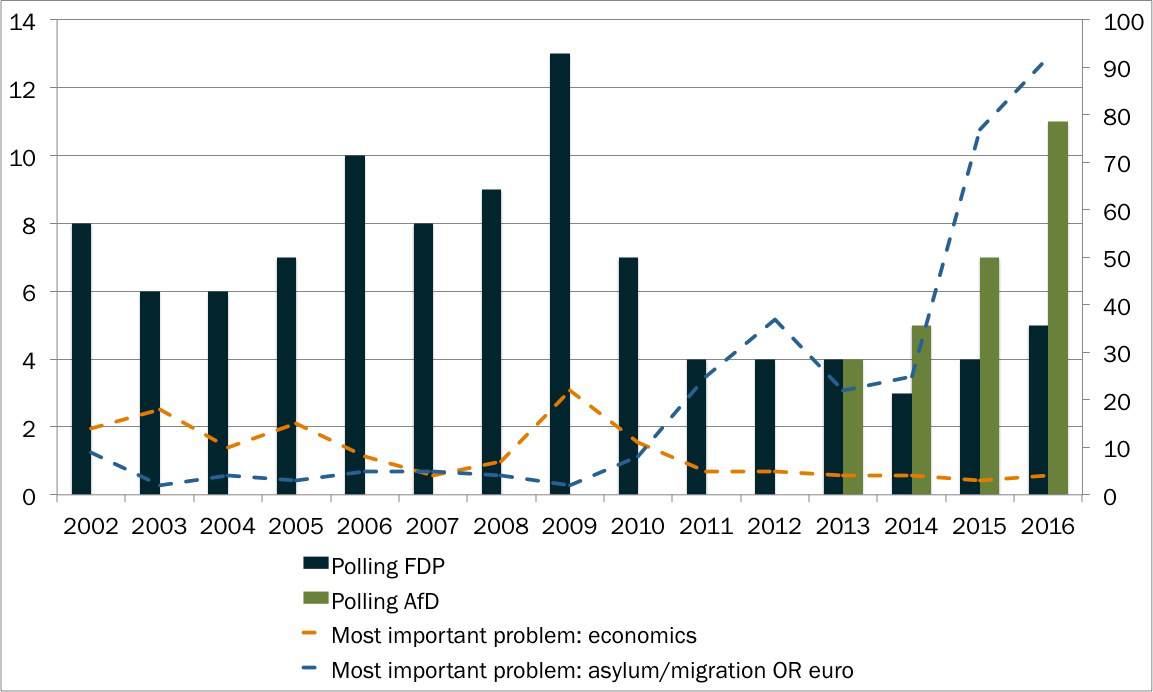

Third, the AfD offered a fiscally conservative alternative to the mainstream conservative parties. The liberal Free Democratic Party (FDP) has traditionally fulfilled the role of a second center-right party in Germany, which attracts a similar, though more economically liberal, voting strata to the CDU/CSU, but it has been polling below the 5% threshold and was thus not considered a political alternative. The AfD has tried to present itself as market-liberal on economic matters as the FDP and as conservative on immigration matters as the CSU, aiming to capture wealthier disappointed conservative voters.

This threefold “winning formula,” which provided the programmatic niche for the AfD in the political spectrum in Germany, could close again. The AfD’s fortunes are largely dependent on the mainstream parties, especially regarding the migration and protest niches. AfD party strategists know full well that they benefit when voters’ concerns are not being addressed by the main parties.

The three large parties (CDU, CSU, and SPD) have already shown that they can swiftly forge a conservative compromise, as they did after the Cologne attacks on New Years’ Eve, when criminals with migrant backgrounds sexually harassed and assaulted hundreds of women. Within days of the attacks, the Social Democrat justice minister, Heiko Maas, reached an agreement with the Christian Democrat interior affairs minister, Thomas de Maizière. They called for tightening of integration legislation, a large increase in police capabilities, and swifter deportation of asylum applicants who have committed serious crimes. These policy proposals are the reason that the AfD only saw a small boost from the Cologne attacks, and has plateaued since January 2016. The integration law from the summer of 2016, which defined demands and opportunities for migrants and refugees, was also designed to address conservative voters’ concerns.[6]

In July and August, even as AfD was dipping in the polls, the number of arriving asylum seekers was rising steeply.

A similar pattern was evident in the summer of 2015 as the CDU/CSU and the SPD took a very tough, united stance on Greece, and support for the AfD dropped to 4%. The AfD emerged in 2013, focusing on the eurozone debt crisis and Germany’s EU budget contributions, and polled well during the peak of the negotiations over the eurozone crisis in 2014 and into early 2015. Meanwhile, a right-wing extremist movement calling itself Patriotic Europeans Against the Islamization of the Occident (PEGIDA) held rallies in eastern cities such as Dresden. Some in the AfD flirted openly with PEGIDA and thereby reached out to more groups of voters. In December 2014, AfD polled at around 7%.

The party had a hard time consolidating its gains, however. In mid-2015, it became known that German Finance Minister Wolfang Schäuble (CDU) was taking a harder line on eurozone issues, suggesting that Greece should either meet German demands or quit the common currency. In addition, the AfD was splitting between the euroskeptics around Bernd Lucke and a nationalist wing around two other leaders, Frauke Petry and Alexander Gauland. Lucke wanted the AfD to be a market-liberal party focused on eurozone matters; his rivals wanted to expand into criticism of multiculturalism and immigration in order to forge a full-fledged right-wing populist platform. In July 2015, the split became formal. Petry took over as the AfD’s new leader, while Lucke went off to found a new party that has yet to make a mark. Bad press sparked by the disarray, along with the government’s ability (thanks to Schäuble) to reclaim Euroskeptical voters, drove AfD down to about 3% support in July and August 2015 surveys.

But Petry’s widening of the party program paid off later in 2015. In July and August, even as AfD was dipping in the polls, the number of arriving asylum seekers was rising steeply. In September, Merkel made her fateful decision to accept the refugees stranded at the Budapest train station, a move that was taken as a signal that Germany would accept not only all who had already arrived, but even those still heading to Europe. As the parties of the governing coalition argued about closing German borders in October 2015, the AfD rose from its nadir of around 3%

support in August 2015 to four times that level to 12% in January 2016.

However, since January the AfD’s rise has halted. The ringing denunciations of multiculturalism that the AfD added to its call for border controls after the widely publicized New Year’s Eve attacks in Cologne and other cities did not help the party as much as it might have. Their momentum was halted when the EU and Turkey struck their deal to close off the Balkan migration route in March 2016, leading to a large drop in the number of new arrivals. In addition, the integration law from spring 2016 seems to have allayed some concerns.

However, conservative German voters are not yet convinced by mainstream party proposals to address integration. German politicians will need to be far more outspokenly conservative about integration and migration topics (e.g. very clear messaging in support for increasing deportation of illegal refugees) in the coming months if they want to convince conservative voters to turn away from the AfD, and repeat the polling trends seen around the Greek bailout debate in spring and summer 2015 (Figure 4).

The AfD is particularly dependent on the strategies of other parties, as its agenda setting capacity is limited. Reacting to a changing discursive climate requires stable media access, solid party structures, and an agreement of the party leadership on the general course. So far the AfD is lacking all three.[7] Once the party can rely on structures similar to those of the French Front National (FN) or the Austrian Freedom Party (FPÖ), the political processes become more complicated. But as the AfD is still unconsolidated, it lacks agenda-setting capacity. This means that most of the agency is with Germany’s other parties – for the time being.[8]

Right-Wing Problems with Economics and Extremism

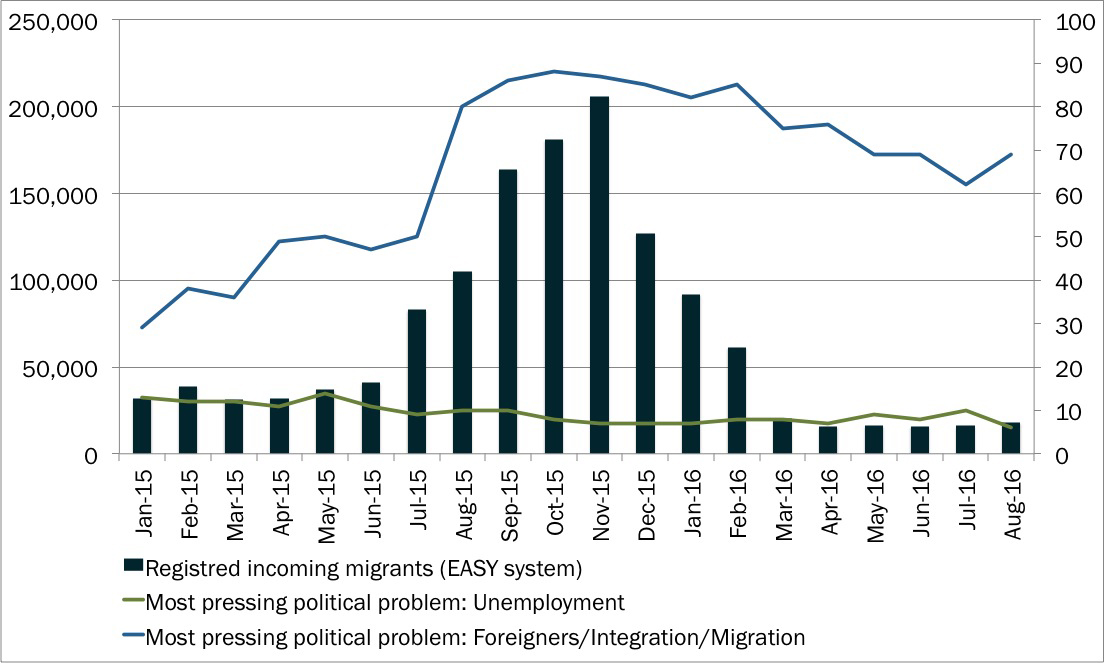

The AfD’s success with fiscally conservative voters, is extremely tenuous, as it lacks a program and issue competency. The Liberals, or FDP, have been the fiscally conservative alternative to, and often partner of, the Christian Democrats since the 1980s. AfD, which began life as an anti-euro party, benefited from the FDP’s weakness in the past few elections. But now the FDP is showing signs of renewal, polling between 6 and 8%, and could draw voters back from the AfD.[9] The FDP crossed the 5% electoral threshold at the 2016 regional elections in Baden-Wuerttemberg (8.3%), Rhineland-Palatinate (6.2%), and Berlin (6.7%), and almost in Saxony-Anhalt (4.9%) – an eastern German state where the liberal FDP traditionally has problems. This climb has happened in a time when the Liberals’ prime campaign topic – economics – has been almost entirely absent from the German debate (Figure 5).

Bringing back economics will not only help the FDP – it will weaken the AfD and allow mainstream parties to play to their strengths, as we have seen elsewhere in Europe.[10] The German discourse over the past few elections has been concerned with matters of national identity or culture (Europe and migration) rather than economics. When economic topics are salient, fiscally conservative voters tend to see their demands met by the program of the center-right parties, while conservative workers look to the SPD. When matters of national identity dominate the debate, the mainstream conservative party’s profile in cultural matters is the main determinant of whether conservative voters stick with established actors. Because Germany’s governing conservatives were not capable of communicating clear-cut conservative positions on EU and migration matters, the electoral niche for the AfD’s anti-EU, anti-migration, anti-Islam program opened. If socio-economics topics resurface, the AfD (which does not

have the voters’ trust on economic issues) will struggle to keep voters’ support (Figure 6).

If mainstream parties campaign on economic issues and offer different visions, voters will get the impression that the established elites are competing for the best solution for the country, rather than preserving a status quo that keeps them in power. While conflicts among governing parties over matters of national identity and security are perceived as endangering the nation, conflict over socio-economic positions makes voters feel like the parties offer genuine alternatives. Thus if the CDU/CSU and the SPD manage to campaign on fierce economic polarization, the AfD’s anti-elite narrative, fueling the protest vote, will lose force.

The AfD might not only see its topical niche evaporate, it might also lose support through its party leaders’ extreme comments. In the winter of 2015, some AfD politicians proposed preventing border crossings at gunpoint.[11] The head of the regional chapter of AfD Thuringia, Bjoern Hoecke, took positions in late 2015 that drew accusations that he was being anti-democratic and neo-fascist.[12] At the party convention in April 2016, party leadership had to maneuver very carefully to not let the far right sentiments’ within its rank and file become part of the party platform.[13] However, the party still took a clear-cut cut anti-Islam line that seems to be at odds with the German constitution, which forbids discrimination by religion. In June 2016, AfD vice chairman Alexander Gauland gave an interview to the conservative newspaper of record Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung in which he said that “Germans like Jerome Boateng as a footballer, but do not want him as a neighbor.”[14] Germany’s conservative media fiercely rejected this attack on a member of a central symbol of German national pride – the football team that won the World Cup in 2014.[15] The more mainstream conservative voter strata might grow weary of these kind of extreme comments and turn away from the AfD.

In the 1990s, a different right-wing party suffered a similar fate. The Republikaner (REP), a right-wing nationalist, anti-immigration party, emerged on the scene and quickly climbed to 8-10% in the polls at its height in 1992. But as accusations of its right-wing extremism continued to grow louder, and German conservative voters were appeased by the “Asylkompromiss” of 1992/1993. In addition, the electoral campaigns of 1994 featured fierce debates about economic policies between the CDU/CSU and SPD. The REP dropped below 2% support at the federal election in 1994. The very same mechanisms could come together to weaken the AfD.

How Weak is Germany’s Political Center?

Just a year ago, Merkel’s political dominance seemed untouchable, whatever the policy twists and turns. However, the refugee crisis revealed internal party conflict that has led some commentators to predict a steep fall for Merkel and the CDU. Four groups are most prominent in relation to the chancellor’s course. The first group, led by prime minister of Bavaria and chairperson of the CSU, Horst Seehofer, has been the most outspokenly critical. The second group is made up of other key figures within the CDU who by and large support Merkel’s policies but have at times voiced their criticism, including Schäuble and de Maizière. Over the spring of 2016, candidates for the prime minister positions in two southern German regions – Julia Klöckner of Rhineland-Palatinate and Guido Wolf of Baden-Wuertemberg – begun to form a third group.

Policy-related concerns and party-internal interests seem to motivate these critics. For Seehofer’s criticism to be a credible threat to Merkel, he needs support from leading politicians within her party. While Schäuble and de Maziere, two of the most prominent CDU members, have been publicly critical of the chancellor’s course on migration, they supported her attempts to find a “European Solution” and the arrangement with Turkey. Criticism from Klöckner and Wolf was largely motivated by the strategy to win conservative voters in their regional elections in mid March.[16]

With far fewer asylum seekers arriving, all three groups now have far fewer incentives to criticize the chancellor in the run-up to the federal election in 2017. The CDU/CSU and the SPD drafted encompassing conservative integration legislation in summer 2016, largely taking Seehofer’s positions into account, while the CSU has risen in the polls in Bavaria.[17] After both Klöckner and Wolf did not manage to come out strongest in their regional elections (the SPD was stronger in Rhineland-Palatinate and the Greens in Baden-Wuerttemberg), their influence within the CDU/CSU has weakened.

If the numbers of incoming refugees increase significantly again and Angela Merkel then still refrains from introducing border controls, internal challengers and critics will quickly re-emerge.

If the numbers of incoming refugees increase significantly again and Angela Merkel then still refrains from introducing border controls, internal challengers and critics will quickly re-emerge.[18] However, if the numbers of incoming refugees remain low and the government manages to clearly communicate conservative integration legislation, there will be fewer incentives for key CDU and CSU politicians to criticize Angela Merkel’s policies. That said, it is not yet clear if the CDU/CSU and SPD have identified a consensus conservative position on integration.

Interestingly, Germans remain relatively calm about the financial aspects of integration. The direct costs of accommodating the 1.1 million incoming refugees in 2015 are estimated to be between €17 and €30 billion.[19] Given that the government estimates that another 500,000 refugees will arrive in 2016,[20] research institutes calculate the total costs for 2015 and 2016 to be around €40-60 billion. The German government calculates roughly similar figures.[21] These additional costs would seem to pose a challenge the famous/infamous “Schwarze Null” – the balanced budget especially dear to German conservatives. However, the unexpected increased tax revenues of the last years seem to almost neatly cover the costs arising from the refugee situation, so that the short-term costs of integration have so far not turned out to be a contentious issue (Figure 7). A case in point was the ease with which German party leaders reached an agreement in mid-March to spend additional €5 billion more to aid the integration of migrants.[22] For a change, spending money is of no major concern to German voters.

Similar to the migration issue, terrorist attacks alone are unlikely to have a palpable impact on the election in 2017, though the political messaging after such an attack would be crucial. The united conservative reaction of the governing parties after the Cologne attacks on New Year’s Eve and the terror attacks over the summer in southern Germany prevented the AfD from benefitting from these developments. If the German governing parties continue to remain united in the face of the next attack, and do not promise conservative policies in response that they cannot deliver, they leave little room for anti-elite arguments to gain traction.

A Conservative Compromise

The AfD’s big wins in recent regional elections are not a sign of an unstoppable national trend. There is a good chance that Germany will continue to have a political party configuration that will lead to a solid pro-European government resulting from the federal election in September 2017. With the sharp decline of incoming refugees over the winter of 2015-16, the likelihood of socio-economic topics resurfacing in the German debate, and the AfD struggling to reign in its right-wing extremism, chances are high that German voters will return to the established parties over the coming year. This return depends less on political events such as eurozone negotiations, migration crises, or international conflicts, than it does on how the CDU/CSU and the SPD communicate to the German voters on matters concerning national identity and economics.

If Germany’s mainstream parties can agree on a conservative compromise on EU, migration, and integration issues, support for AfD will again drop off. Once such a compromise is found and consistently communicated, mainstream parties can campaign on socio-economic issues, where they are strongest, benefitting mainstream parties on either side of the center. The integration legistlation introduced after the Cologne attacks indicates that Germany’s mainstream parties can find such compromises.

As a result, prospects for established German political actors are more promising than current polling suggests. Even though the AfD’s prospects appear bright after receiving 20% at the election in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern and 14% in Berlin in September 2016, it is still polling nationally at between 11 and 13%, as it has since January. And it still lacks independent agenda-setting power. Thus if Germany’s mainstream parties keep their messaging tight, the AfD is likely to lose most of those voters who turned to it in protest against Merkel’s refugee policies (in some regions, this is up to two-thirds of their supporters). Even if the AfD does succeed in becoming the first far-right party to break the 5 percent barrier in German federal elections, the chances are high that the overall election results will return a centrist government with a stable pro-European majority to power. Without a new surge in the inflow of migrants and refugees, the German center still looks likely to hold.

[1] The CSU only exists in Bavaria. The CDU never stood for election there, while the CSU refrains from reaching out to other states. The CSU is often described as the CDU’s “conservative wing.”

[2] Results of federal polling for AfD support vary between 11 and 13%, as measured by various independent research institutes (very few outliers not accounted for). These results are listed at http://www.wahlrecht.de/umfragen/.

[3] Lochocki, Timo (2014). “The Unstoppable Far Right?” GMF Europe Policy Paper 4/2014. www.gmfus.org/publications/unstoppable-far-right

[4] Lochocki, 2014 .

[8] Bornschier, S. “Why a right-wing populist party emerged in France but not in Germany: cleavages and actors in the formation of a new cultural divide.” European Political Science Review, 4(1), pp. 121-145, 2012.

[10] Ivarsflaten, E. “The vulnerable populist right parties: No economic realignment fuelling their electoral success.” European Journal of Political Research 44: pp. 465-492, 2005.

[14] http://www.faz.net/aktuell/politik/inland/afd-vize-gauland-beleidigt-jer... Boateng, born in Germany, has a German mother and Ghanaian father.