Alliances in a Shifting Global Order: Indonesia

Indonesia: Maintaining Pragmatic Equidistance

by AARON CONNELLY

Read the full report here.

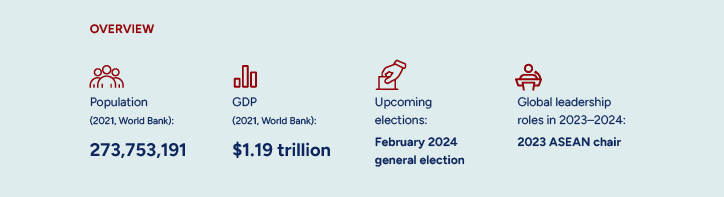

With its long history of nonalignment, Indonesia is determined to continue its tradition of remaining aloof from great power rivalry and maintaining a pragmatic equidistance from Beijing and Washington. This does not exclude the possibility of cooperation with either when it serves Indonesian interests. But it does incentivize Jakarta to identify partners elsewhere —in Europe, Russia, or the Gulf—for the defense systems, trade and investment, and technology needed to ensure security, domestic political stability, and increased living standards for its 270 million people.

Still, a Bias Toward Beijing

Indonesian policymakers tend to view rising US-China tensions as the greatest threat to regional security. They work to manage exposure to the risks of alignment with either power by avoiding even the perception of it. Senior officials, however, tend to discount the threat that Chinese actions present to peace and security while they question the sincerity of US officials who portray American positions as deterrent rather than escalatory. This has resulted in slightly more sympathy for Beijing than for Washington on Taiwan, the US defense of which would depend on access to Indonesian sea lanes.

Jakarta seeks to quietly manage, without American assistance, a dispute in the South China Sea that involves competing Chinese and Indonesian claims. There is no desire to give Beijing a pretext to perceive the dispute as a proxy for US-China competition. But that does not mean Indonesia will stand idly by when its territorial integrity is at stake. The Indonesian armed forces (TNI) responded with shows of force when Chinese coast guard ships confronted them in 2016 and 2019, despite knowing that any dispute that resulted in casualties would have been difficult to manage.

The TNI were once heavily reliant on American weapons systems, but they diversified their defense supply chain in the 1990s. Following the imposition of US sanctions in response to human rights abuses, Indonesia turned toward Russia, Europe, the Middle East, and South Korea. Russia is no longer a supplier due to US sanctions, giving European manufacturers an opportunity to seize Moscow’s former market share. The TNI still aspires to acquire high-end American systems, but price and restrictions on technology transfer complicate any purchase.

China Lends a Hand

Two of President Joko Widodo’s trade and investment policies—related to constructing a vast transportation infrastructure network and to a series of raw minerals export bans—have made China Indonesia’s preferred economic partner. Beijing has financed many highly visible development projects, such as railways, roads, airports, and seaports, that have been political winners for the presdient, also known as Jokowi. The ban on raw minerals exports, particularly that for nickel, has also been a success. It spurred Chinese investment in processing facilities that have allowed Indonesia to move up the value chain. This fulfilled a long-term goal of Indonesian economic planners and defied warnings from Western businesses that the gambit would not work.

The Jokowi administration has also prioritized certain green industrial sectors, particularly batteries and electric vehicles, to boost exports. At the same time, the government has been reluctant to reduce its use of coal for electricity, much of which is produced by Beijing-financed power plants. The details of a Western-backed Just Economic Transition Partnership (JETP), which would compensate Indonesia for closing its coal-fired plants, are under discussion. But monitoring and implementing the decarbonization of the Indonesian economy is likely to be challenging and could create friction with donors in Europe and the United States.

The China-ASEAN Free Trade Agreement, which went into effect in Indonesia in 2010, and the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership, a free trade pact among Asia-Pacific states that entered into force this year, more closely bind the Indonesian and Chinese economies. Similar efforts with other powers lag. Indonesia has been negotiating a free trade agreement with the EU for the past six years, and the country is part of the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework for Prosperity talks with the United States, but these efforts are unlikely to conclude soon or in a way that changes the structure of Indonesia’s trading relationships. Jakarta’s dirigiste economic policies have made it a frequent target of industrialized countries’ complaints at the World Trade Organization, where it tends to align itself with the Global South. Indonesia’s large palm oil industry, which, the EU alleges, accelerates deforestation and climate change, has emerged as a particularly thorny irritant in the country’s relations with Brussels.

But the top investment priority for the Jokowi administration, now in its second term, has been the construction of a new capital carved out of the forests of Borneo, at a cost of $34 billion. The government intends to fund only 20% of the cost and rely on foreign investors to cover the rest. It has struggled to raise the necessary funds and, wary of the perception that it has become too reliant on China, has focused on attracting financing from Japan and the Persian Gulf. The government may still need to turn to Beijing, which would have significant implications for Jakarta’s geopolitical positioning.

No Worries

In the digital sphere, Indonesia has set the acquisition of advanced technologies at low prices as the priority. It has little concern for the implications of working with suppliers from countries that may pose a cybersecurity threat. In this sector, too, Chinese firms have emerged as partners of choice. Indonesian officials tend to dismiss evidence of the risks of working with them and cite documents leaked by former US National Security Agency contractor Edward Snowden to argue that China is not alone in spying on Indonesians. Regulators of digital services share neither their European counterparts’ concern for privacy nor their American counterparts’ concern for free speech.

Wary of the West

Regarding the international order, Indonesia advocates placing the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) at the center of regional diplomatic architecture, allowing the group of ten small states to host and chair discussions among the world’s great powers. Indonesia, along with several of its neighbors, is wary of initiatives that could dilute ASEAN’s influence. The Quad is one such initiative, as it is perceived as a forum in which discussions about Southeast Asia’s future occur without the presence of the countries that comprise the region.

Indonesia may be the world’s fourth-most populous democracy, but it identifies more closely with the states of the Global South than with Western powers. Jokowi has crafted an increasingly illiberal society by working with legislators to pass laws circumscribing free speech, while the police have used preexisting statutes to prosecute and jail popular advocates of political Islam.

Indonesian reaction to Western criticism of these trends is influenced by the country’s history and geography. Leaders of Indonesia, an archipelagic state that endured three centuries of Dutch colonization, have long worried that great powers might again seek to divide its many islands and seize their resources. In the Cold War’s early years, Western nations, including the United States, lent credence to these fears by seeking to foment separatist rebellions in resource-rich provinces amid ideological competition with the Soviet Union. The result has been an enduring sensitivity about territorial integrity and a suspicion of Western motives, particularly when issues of democracy and human rights are involved.

Read the full report here.