Parliamentary Diplomacy in the Western Balkans

Summary

Diplomacy is more comprehensive and multilayered than ever. Today it goes beyond representation, negotiation, communication, reporting, and policy analysis, and it enlists other actors at the state level besides Ministries of Foreign Affairs to shape international affairs. At the same time, there has been the rise of new channels of communication and the traditional channels of diplomacy are increasingly being circumvented.

As their country’s highest legislative institution, parliaments ratify international treaties. They have foreign affairs committees and their speakers or presidents deal with foreign affairs in their daily activities. They also conduct interparliamentary cooperation through delegations to various international parliamentary organizations and bodies or bilateral parliamentary groups. National parliamentary delegations are constituted in a way that aims to ensure an equitable representation of political groups in their parliament. Interparliamentary cooperation at all levels generally aims for a closer dialogue with regional and strategic partners. By acting internationally, parliamentarians can contribute to their country’s public, cultural, or economic diplomacy as well as gain practical experience in key policy areas. At the same, they represent their country and can exchange good practices and experiences with their peers from other countries.

The parliaments of the Western Balkans all practice these different aspects of parliamentary diplomacy as an important part of their role and activities. It may influence how each of the region’s six countries—Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo, Montenegro, North Macedonia, and Serbia—implements its foreign policy goals, particularly with respect to European Union integration. Alongside regional parliamentary cooperation among the Western Balkan countries themselves, cooperation between the European Parliament and the member states’ parliaments are also key to the success of the integration process.

By acting internationally, parliamentarians can contribute to their country’s public, cultural, or economic diplomacy as well as gain practical experience in key policy areas. At the same, they represent their country and can exchange good practices and experiences with their peers from other countries.

Interparliamentary cooperation is critical for realizing the aims of the Berlin Process. Launched in 2014, this initiative aims at ensuring good relations among the Western Balkan countries and supporting their integration into the EU. This would have greater potential of success if parliaments were more directly involved, yet, for nearly eight years, the parliaments of the six countries have not been a part of the Berlin Process. This absence is consequential as joining the EU is the foreign policy goal of each of the region’s countries.

For parliamentary diplomacy by the Western Balkans legislatures to be effective, some requirements must be met. The first and most basic precondition is having strong parliaments, and the six countries need to take steps toward building resilient parliaments. This is achievable by building strong and independent institutions through the strengthening offices and parliamentary service of their members. Parliamentarians need to further develop their real potential and power—especially in international activities where a huge potential is currently squandered.

Equally important is regional ownership of any initiative addressing issues relevant for the future of the Western Balkans. Regardless of the fact that EU accession is guided by Brussels and the member states, a regional approach and expanded regional initiative would add value by demonstrating the region’s proactivity, and enthusiasm. Most importantly it could originate from the people themselves, as represented by their parliaments. Interparliamentary conferences, under the framework of the Berlin Process, could bring together the foreign affairs committees from each of the six countries on a regular basis, thereby contributing to the integration agenda as well as enhancing regional cooperation and good neighborly relations. Parliamentary working bodies have the potential to launch such an important regional dialogue, providing oversight over the implementation of the result-oriented Berlin Process arrangements. They can thus foster the parliamentary diplomacy necessary to achieve the “European dream” in the Western Balkans.

Introduction

Parliamentary diplomacy as an emerging practice is gaining more attention. It affects and complements traditional diplomacy in daily governance and political practice, adding value to a country’s international relations overall. Globally there is a trend of parliaments engaging in foreign affairs directly and autonomously as relevant and respected actors. While every national parliament has a working body for foreign affairs, their speakers also engage directly in international relations through interactions with foreign officials and international organizations. More flexible, adaptable, and faster than traditional diplomacy, parliamentary diplomacy is rapidly shaping bilateral and multilateral cooperation.

In the Western Balkans parliamentary diplomacy is affecting regional ties regardless of current relations between the six countries—Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo, Montenegro, North Macedonia, and Serbia. A turbulent past as well as similar current challenges and visions for the future are things these countries share. Commitment to European integration also remains high on their political agendas. United by the same goal, the Western Balkans countries strive to meet all EU membership requirements. Their cooperation at the bilateral and multilateral levels is in continual development. Each of the region’s parliament has placed diplomacy high on the agenda, which is seen at the highest parliamentary levels as well as in the wider structure of international cooperation between them. As it is currently developing, parliamentary diplomacy in the Western Balkans may increasingly influence the implementation and achievement of each country’s foreign policy goals. This is especially the case when it comes to EU integration. An empowered, strong, and efficient democratic parliament is a critical factor for EU accession. These parliaments must drive change and introduce effective and substantial reforms needed to achieve the “European dream” pursued for generations in this region.

As a primary forum for dialogue and debate on key national issues, and a place where members discuss political matters, engage with contrary opinions, hone arguments, and seek consensus, each parliament must respond to the expectations of their citizens. The majority of citizens across the Western Balkans endorse the goal of joining the EU, as a community embracing the universal values of human dignity, freedom, democracy, equality, rule of law, and human rights, as well as a union of developed countries with many opportunities for personal welfare. Integration also plays an important role in reconciliation across the region.

In this context, the Berlin Process—the initiative launched in 2014 by Germany’s Chancellor Angela Merkel, aimed at enhancing regional cooperation and reconciliation, and thereby speeding the EU accession process—has a greater potential to succeed if parliaments get involved more directly. As an initiative with a heavy governmental focus, it has grown to be an important forum for cooperation in the Western Balkans, yet it lacks parliamentary diplomacy. Not only is this a glaring discrepancy in the practice of parliamentary diplomacy across the Western Balkans in other multilateral initiatives, but also the exclusion of parliaments inhibits transparent, inclusive, and comprehensive information from reaching the representatives elected by citizens. As representatives of the people, parliamentarians have legitimacy to contribute of the Berlin Process and provide oversight of it. Therefore, a stronger parliamentary dimension would result in a stronger Berlin Process.

Parliamentary Diplomacy

Diplomacy is no longer the sole purview of governments. The fields of commercial diplomacy, economic diplomacy, business diplomacy, open diplomacy, coercive diplomacy, preventive diplomacy, bomber diplomacy, paradiplomacy, cultural diplomacy, public diplomacy, celebrity diplomacy, sports diplomacy, and parliamentary diplomacy illustrate that the range of international actors has expanded considerably.1 Among this broad palette of diplomatic actors, parliaments are increasingly assuming a leading role. Parliamentary diplomacy is developing in a such a way that it is transforming the perception of diplomacy in general, while also reducing the democratic deficit in foreign policy. The term comprises all forms of cooperation between members of parliaments, as well as the many foreign activities or meetings they may engage in. By fostering cooperation, promoting political dialogue, and engaging actively in the international arena, parliaments and parliamentarians are emerging as increasingly relevant and significant international actors. Parliamentarians regularly participate in parliamentary assemblies of international organizations and other multilateral forums, conduct official visits to foreign countries, receive foreign officials, and especially at the level of speakers they are included in the visit programs of the highest foreign representative. While still a developing concept, it is clear that parliamentary diplomacy is more flexible and informal than traditional diplomacy. As such, it complements, enriches, and stimulates traditional diplomatic channels. Parliamentary diplomacy need not be conducted exclusively between parliamentarians either—it can also entail them visiting another country for meetings with their authorities and entities in consultation over conflicts and problems.

Parliamentarians can be much more flexible than government representatives in conducting diplomatic activities. They add a dimension of pluralism to diplomacy, especially when bringing together different political colors and voices exemplifying a stable and well-functioning democracy. Further, they can build bridges between conflicting parties, unshackled by instructions from governments. Parliamentary diplomacy provides a forum to promote political dialogue and to address and smooth over misunderstandings or even conflicts in neighboring countries and within one’s region. The deployment of parliamentary contacts to promote the international democratic legal order and also the development of personal contacts between members of parliament from different countries enable greater mutual understanding and are beneficial for bilateral relations.2

Historically, except for their role in ratifying international agreements, parliaments did not use to have much involvement in international affairs. But globalization has increased the need for greater cooperation in political, economic, and social activities, stimulating the creation of interparliamentary organizations, incorporating various forms of parliamentary cooperation at the global and regional levels. All parliaments take part in bilateral cooperation of some kind, mostly through bilateral parliamentary groups, common known as friendship groups, that promote ties between the parliaments and countries concerned. There are also networks of parliamentarians that work on specific transnational issues.3 Speakers engage in international cooperation with their foreign activities, while parliaments often cooperate through, primarily, their foreign affairs committees. Contemporary forms of parliamentary diplomacy are sophisticated tools of progress and illustrate the maturation of interparliamentary cooperation in a world that needs exchanges that are globalized, interdisciplinary, intercultural, and especially participatory.4 This is an irreversible development as parliaments globally dedicate ever more time and resources to such cooperation. Worldwide, parliamentary diplomacy embodies an increasingly significant component of each country’s foreign policy individually as well as of global politics overall.

In the context of the Western Balkans, parliamentary diplomacy can be of great value in the EU enlargement process. It opens new ways and channels to strengthen international support for the six countries’ EU perspective.

In the context of the Western Balkans, parliamentary diplomacy can be of great value in the EU enlargement process. It opens new ways and channels to strengthen international support for the six countries’ EU perspective. Regular contact with the European Parliament and the parliaments of the member states, as well as regional parliamentary cooperation among the Western Balkan countries, are key to the success of the integration process. National parliaments embody the best link between the EU and national levels in the transmission of standards, values, and principles.

The Western Balkans Parliaments

Parliaments are essential for democracy. As the central institution elected to represent the whole of society, they hold the unique responsibility of reconciling the interests and expectations of different groups through dialogue and compromise.5 Parliaments need to promote, facilitate, and foster democratic values and to be the forum for debate reflecting the opinions of those they represent. Democratic parliaments are representative of the diversity of the people and ensure equal opportunity and protections for all. They are transparent, in their openness to the public as well as in the conduct of their work. They are accessible, involving the public and civil society in their work. They are accountable, in that their members are accountable to the electorate for their performance in office and the integrity of their conduct. And they are effective, in organizing their business in accordance with democratic values and in performing legislative and oversight functions to serve the needs of the people.6

The parliaments in the Western Balkans are still rising to the challenge of fulfilling all these requirements as democratic institution. Nevertheless, they tend to be relevant actors internationally as well as nationally. In addition to their general functions, they play a crucial role in the process of harmonizing and approximation of national legislation with EU acquis and standards as well as in monitoring the course of accession negotiations. Not only do they reflect the diversity of national opinion in this regard, they also play a critical role in transmitting EU ideas, values, and visions back to citizens, helping them understand the entire process by facilitating and advocating it. Each Western Balkans country is currently ruled by a majority of pro-EU parties whose primary goal is integration, dedicating energy and structuring work to fulfill reforms and adopt EU standards. Albania, Montenegro, North Macedonia, and Serbia are candidate countries, while Bosnia and Herzegovina and Kosovo have not yet been granted this status.

Out of the six countries, only Bosnia and Herzegovina has a bicameral legislature at the state level: the Parliamentary Assembly of Bosnia and Herzegovina, which consists of the lower House of Representatives (Predstavnički dom) and the upper House of Peoples (Dom naroda). The other five have unicameral parliaments: the Parliament of the Republic of Albania (Kuvendi), the Assembly of the Republic of Kosovo (Kuvendi), the Parliament of Montenegro (Skupština), the Assembly of the Republic of North Macedonia (Sobranie), and the National Assembly of the Republic of Serbia (Narodna skupština).

The last year and a half turned out to be anything but predictable because of the coronavirus pandemic. Serbia, North Macedonia, and Montenegro held parliamentary elections in extraordinary circumstances in 2020 and Kosovo in early 2021, with all the necessary health measures. The pandemic has altered parliamentary work in general. Beyond national struggles with the unprecedented health care crisis as well as economic and social instability, the Western Balkans parliaments were pushed to adapt to new circumstances and invent new ways of functioning. They moved to working online, adopting decisions and passing laws via online meetings of their members, addressing everything from emergency procedures to legislation in response to the public-health emergency and its economic impacts. Although parliamentary diplomacy in the Western Balkans has been affected by this situation, it did not stop. International parliamentary cooperation has continued throughout the pandemic. Globally, while some argue that multilateralism is in crisis, there are still great efforts toward mutual understanding, collaboration, assistance, and support in the face of this global challenge. It turns out that the pandemic revived much-needed multilateral cooperation.

The Regional Experience

Existing forms of bilateral and multilateral parliamentary cooperation are well established in the Western Balkans, with some countries having more experience institutionally. Each parliament employs parliamentary friendship groups as a bilateral mechanism for cooperation. They are established with each new convocation, when parliament is elected. Friendship groups aim to direct interests in bilateral cooperation and establish or deepen relations between countries. Multilateral groups are rare.7 Such groups stimulate intensified interparliamentary relations while promoting each country’s views on national and international issues of concern. This form of parliamentary cooperation creates opportunities for members of parliament for direct engagement with peers from other countries, predominantly to exchange information, opinions, and experiences. By promoting closer relations between parliamentarians, these groups encourage stronger international partnerships as well.

In promoting dialogue between peers, parliamentary exchanges provide a platform for mutual consultation on regional and global issues and a space to learn from discussions of differing opinions and conflicting views. Formed on a cross-party basis, they tend to mirror parliamentary representation, but also to reflect parliamentarian’s special interest in relations with the country in question. The idea is for members to be affiliated by their personal links, cultural ties, knowledge of language, and issues of particular interest or concern. The groups’ cross-party nature creates an environment of democratic inclusiveness that balances opposing opinions and encourages objective debate. Promoting democratic parliamentary structures as well as common interests and objectives in political, economic, social, environmental, cultural, scientific, and humanitarian fields is an integral part of their role.

In the Western Balkans, not every country pair has established this format, due to differing national interests and positions. For example, Bosnia and Herzegovina and Serbia do not recognize the independence of Kosovo and thus have not formed bilateral parliamentary groups with the latter’s legislators. Still, wherever they are found in practice bilateral parliamentary groups are an effective mechanism demonstrating simultaneously the strength and flexibility of parliamentary diplomacy. This cooperation tool also manifests capacities for managing delicate situations between countries and can play an important role when other governmental means are not delivering results. Where bilateral relations are affected by issues like minority rights or emergent events, one step to facilitate resolution is parliamentary dialogue via friendship groups. In such situations, parliamentarians have acted real agents of change, skillfully mediating and taking first steps toward improved relations. This is one of parliamentary diplomacy’s greatest strengths.

Bilateral interparliamentary activities may also include direct cooperation at all levels, from at the highest level of speakers to working bodies and committees to peer-to-peer parliamentarian exchange, and they typically reflect the immediate interests and priorities of bilateral relations overall. With frequency and constancy of mutual exchange, dialogue, and cooperation, parliamentary diplomacy can enhance a country’s foreign relations on the bilateral and even global level.

Parliamentary cooperation can also be achieved through participation in the work of multilateral parliamentary institutions or other regional and international organizations and initiatives. For the Western Balkan counties regional cooperation and good neighborly relations are an essential part of the EU integration process. As regional cooperation for prosperity and effective reconciliation are essential for stability, the constructive commitment of all six countries to building solid relations with one another in the EU enlargement process serves as an important catalyst in efforts to find satisfactory solutions to open bilateral issues and to work through the legacy of the past across the region.

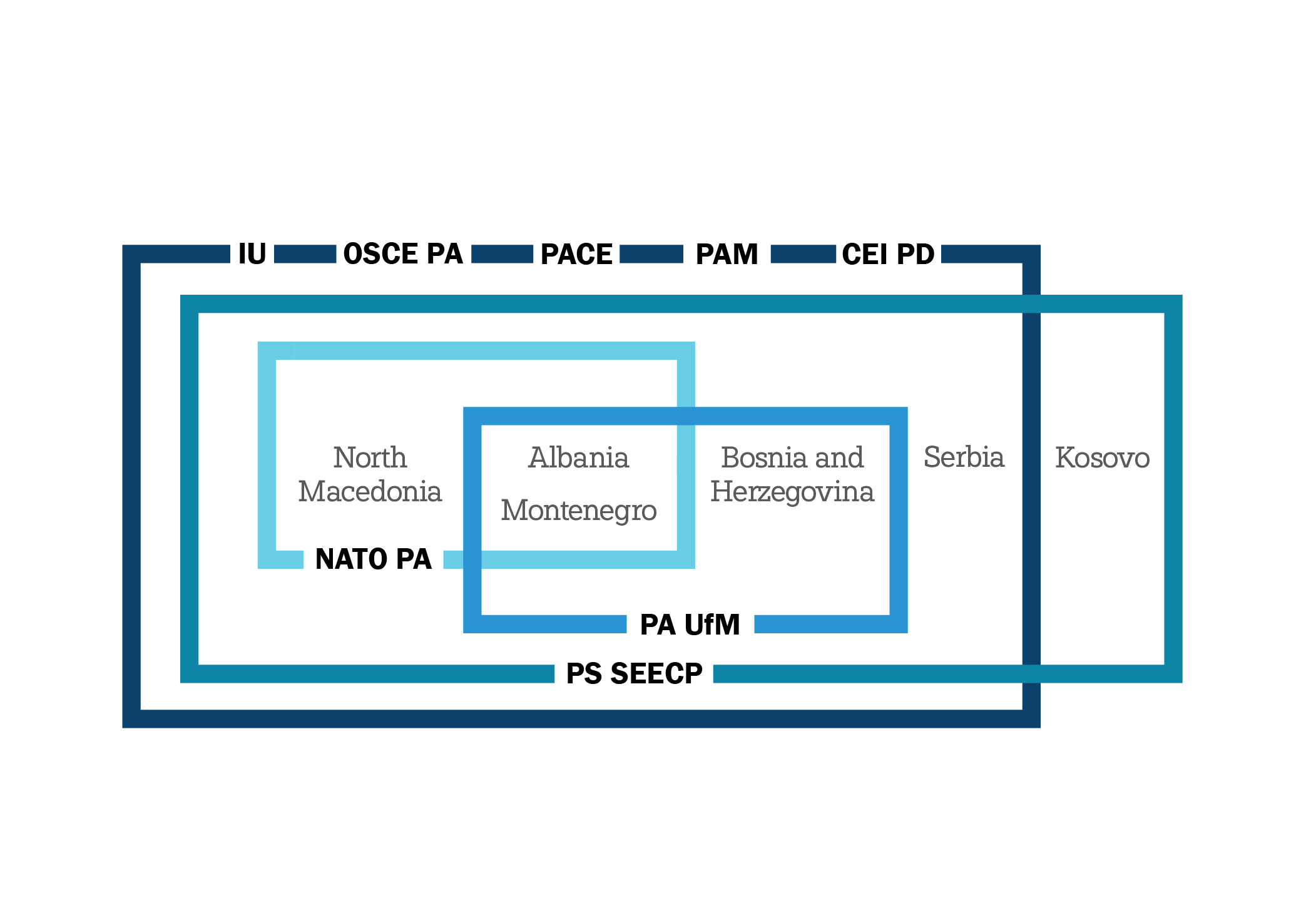

Given the challenge of duplication and overlapping between different international and regional parliamentary bodies, the region’s parliaments prioritize working with certain ones. The most important ones in which some or all of the Western Balkans parliaments participate are the Interparliamentary Union, the Parliamentary Assembly of the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe, the NATO Parliamentary Assembly, the Parliamentary Assembly of Council of Europe, the Parliamentary Assembly of the Mediterranean, the Parliamentary Assembly of the Union for the Mediterranean, the Parliamentary dimension of Central-European Initiative, the Parliamentary Assembly of the South East European Cooperation Process, and the Cetinje Parliamentary Forum. (For details of their participation, see Figure 1.)

Figure 1. Western Balkan countries membership in main international parliamentary bodies.

Established in 2014, the Parliamentary Assembly of the South East European Cooperation Process (SEECP) brings together parliamentarians from each country of the Western Balkans, as well as others from Southeastern Europe.8 Presiding over this body is at times challenging because of conflicting positions between Serbia and Kosovo but nevertheless having all parliamentary representatives at one table is an important step in building political dialogue. Even more significant is the opportunity for the highest-ranking parliamentarians to meet multilaterally, as the head of each country’s delegation of the SEECP Parliamentary Assembly is the speaker of the parliament. This initiative under regional ownership seeks to gather and amplify authentic voices from Southeastern European countries. It was initiated by the region’s parliaments themselves, including those of EU member states, candidate countries, and potential candidates. Core topics of discussion include EU policies and integration; exchange of experiences in legislation and its harmonization with the EU acquis; fostering economic and social development; improvements in infrastructure and energy; cooperation in the field of security, internal affairs and justice; development of human capital; and intensification of parliamentary diplomatic activities. As a cooperation framework set by the SEECP, the Regional Cooperation Council plays a vital role in the coordination of joint activities across Southeastern Europe and in the transposition of political declarations and decisions into specific projects and programs.

The Cetinje Parliamentary Forum (CPF) was one of the first initiative of parliamentary cooperation in the Western Balkans.9 It was established in 2004 to encourage and promote regional interparliamentary dialogue and cooperation between Southeastern European countries on their way toward membership of the EU. The objective is still relevant today. The CPF has adjusted over the years to regional developments and of late it has focused on connecting parliamentarians from Western Balkans countries with their EU neighbors in Croatia and Slovenia.

In addition to the above frameworks of regional parliamentary cooperation, there are parliamentary gatherings at the committee level and regular meetings within each semiannual EU presidency. In their capacity as observers, the parliaments of Albania, Montenegro, North Macedonia, and Serbia participate in the meetings between representatives of national parliaments of EU member states organized during each EU presidency. Particularly important are participation in the Interparliamentary Conference on the EU’s Common Foreign and Security Policy and Common Security and Defense Policy, and the Conference of Parliamentary Committees for Union Affairs of Parliaments of the European Union. Meetings within the parliamentary dimension of each EU presidency carry exceptional importance as Western Balkans parliamentarians have the opportunity to learn directly about the functioning of the union and engage in political dialogue with member-state peers on key economic, social, foreign policy, and other issues.

These committees, as the most competent in this field, have the mandate to consider the EU enlargement process generally and current issues regarding the Stabilization and Association Process specifically. Their most important function is the process of approximation and harmonization with EU acquis of national legislation with the aim of a unified legal structure, facilitating a single zone of freedom, security, justice, and a single market.

The Conference of the Parliamentary Committees on European Integration/Affairs of the States Participating in the Stabilization and Association Process in South East Europe (COSAP) is a regional format aimed at promoting the fundamental internal reforms necessary for integration.10 The member states are Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Montenegro, North Macedonia, and Serbia, with Kosovo participating as an observer. While this conference confirms each country’s willingness and determination regarding democratization, the implementation of reforms, rule of law, respect for human rights, freedom, tolerance, equality, and European values generally, it additionally supports mutual understanding between countries, leading to consolidation and reconciliation across the region. COSAP’s explicit focus is strengthening cooperation between EU integration committees, and it receives support in this from the European Parliament. These committees are recognized as an integral part of the integration process. These committees, as the most competent in this field, have the mandate to consider the EU enlargement process generally and current issues regarding the Stabilization and Association Process specifically. Their most important function is the process of approximation and harmonization with EU acquis of national legislation with the aim of a unified legal structure, facilitating a single zone of freedom, security, justice, and a single market.

Parliamentary Diplomacy and the Berlin Process

With the intention of aiding the EU integration of the Western Balkans as well as fostering and stepping up regional cooperation, the Berlin Process has emerged as a long-term and sustainable instrument for the countries of the region. It aims at ensuring good relations between the six countries and supporting integration as a foreign-affairs priority of the Western Balkans. Launched in 2014, this initiative links the Western Balkans countries and some EU member states11 through concrete, regional, project-based support, ensuring that integration remains a priority across the region. The goals of the Berlin Process are “To make additional real progress in the reform process, in resolving outstanding bilateral and internal issues, and in achieving reconciliation within and between the societies in the region,” as well as to enhance “regional economic cooperation and lay the foundations for sustainable growth.”12 It has delivered substantial progress on these, especially when it comes to economic cooperation and development, integration, and bringing leaders together. Annual summits in Berlin in 2014, Vienna in 2015, Paris in 2016, Trieste in 2017, London in 2018, Poznan in 2019, Sofia in 2020, and Berlin in 2021 have advanced and developed regional cooperation, enriched by the involvement of other international actors. Issues covered by this format range from connectivity to mobility, security cooperation, the fight against corruption, and youth. The most concrete and tangible result of the Berlin Process to date is the Regional Youth Cooperation Office based in Tirana, Albania.

The Berlin Process is not a substitute for the EU accession process but rather its complement. Through cooperation aimed at deeper regional integration, the Western Balkan countries are getting closer to the EU’s single market, which guarantees the free movement of goods, capital, services, and people. The Berlin Process is not only improving regional cooperation, but also preparing individual countries for EU economic integration. As integration is a common foreign policy goal of the six, it has the potential to help overcome regional challenges on the path to EU membership.

Through cooperation aimed at deeper regional integration, the Western Balkan countries are getting closer to the EU’s single market, which guarantees the free movement of goods, capital, services, and people.

Even though the Berlin Process does not have a centralized or fixed structure, regular meetings are held at the governmental level. The annual meeting of heads of state and government—the Western Balkans Summit Series—is held alongside ministerial meetings. Between these summits there are preparatory and expert meetings, as well as meetings between cabinet-level officials. The Berlin Process includes also thematic meetings between civil society, youth, and business fora discussing various regional issues.

Limited Involvement of Parliaments

Unlike many other governmental initiatives, the Berlin Process is completely devoid of parliamentary involvement. Thus far, this dimension has only been achieved via national parliamentary oversight and questions to governments. This has been the only formal way for parliamentarians to gather information and raise questions on the Berlin Process. Lack of involvement suggests that parliaments are not viewed as relevant actors in the process, or in their countries’ foreign policy, but rather as rubber stamps, as all agreements reached by Western Balkan states within this framework will eventually have to be adopted in each national parliament.

Seven years after being established and despite many doubts over its effectiveness among regional and international decision makers, politicians and experts, the Berlin Process is now considered a proven forum. At the November 2020 Sofia summit, showing strong unity and decisiveness while facing a pandemic crisis of global proportions, it demonstrated its full potential and opened new possibilities for this unique cooperation format. Of symbolic significance, in 2020 was the first joint presidency of the Berlin Process by a member state and a Western Balkan country—Bulgaria and North Macedonia— a vital sign of greater ownership over the process by the region.

The Declaration on a Common Regional Market, with its clear objective of deeper regional economic integration and signed by every Western Balkan country demonstrates a common willingness to prepare for a future in the single market, bringing them all another step closer to full EU membership and forging a unified political legacy. In terms of tangible outcomes, a Common Regional Market will be greatly facilitated by the EU Economic and Investment Plan for the Western Balkans adopted by the European Commission last October.13 When it comes to the membership perspectives of Western Balkan countries, the EU Economic and Investment Plan, has the potential to make positive changes throughout the region via concrete and visible action. With a substantial investment package mobilizing up to €9 billion in funding for the region, it provides meaningful support in transforming the Western Balkans. The basic principles of the Economic and Investment Plan are providing economic recovery, strengthening economic growth, promoting green and digital transitions, fostering regional integration and infrastructure, and facilitating convergence with the EU. But none of this will be possible without fundamental reforms in all six countries. Advancing the rule of law, human rights protection, and public administration reform remain crucial for the EU and its further support. Thus, boosting investment and economic growth will be feasible only if the countries decisively commit to implementing necessary fundamental reforms in line with European values.

When it comes to the Common Regional Market, the goal of the European Commission is to support internal economic integration and reduce barriers between the Western Balkan countries, with expectation of intensified integration into the EU single market. Focusing on key deliverables, building a Common Regional Market requires connecting economies, free movement of goods, free movement of services, free movement of capital, regional investment space, regional innovation space, digital market, mobility of people, and European value chains as stepping stones to integrate the region more closely with the EU.14 Given its results-oriented approach and backed up at the Sofia summit by all Western Balkan countries, the Common Regional Market must be subject to oversight mechanisms within their respective parliament from Day One.

Another important outcome of the summit in Sofia was the Declaration on the Green Agenda for the Western Balkans, with all six countries expressing their commitment to working together toward a green and sustainable future. The ambitious but achievable target of a 2050 carbon-neutral continent implies strict climate policies along with transformed energy and transport sectors. The green agenda sets out concrete actions on climate, energy, mobility, circular economy, depollution, sustainable agriculture and food production, and biodiversity. Such a comprehensive framework requires substantial reforms, policies, plans, strategies, and above all implementation. The six countries have committed to environmental protection and fighting climate change together by decarbonization and reducing greenhouse-gas emissions, adopting and implementing climate-friendly policies, promoting energy efficiency, increasing renewable energy sources, decreasing and eliminating coal subsidies, building smart infrastructure, applying innovative technologies, minimizing waste, developing circular economies, depolluting the air, water and soil, promoting sustainable agriculture and food production, and defending biological diversity.

Benefits of Including Parliaments

In reaching these goals, regional cooperation needs to be strengthened and expanded beyond government and ministries and civil society. Parliaments can add value in achieving the objectives. Besides their expertise and knowledge, parliamentarians often have good, fresh ideas that can be invaluable assets to national-level efforts and objectives. Engaging them would create opportunities for synergies. By contributing their knowledge in national and regional affairs, in drafting, negotiating, and passing legislation that meets EU standards in environmental policies, and in approving the economic transition to a common Western Balkans market, parliamentarians have a tremendous responsibility and an opportunity to engage more concretely in the Berlin Process.

Their most important role would be through existing parliamentary oversight and control mechanisms, exercised in plenary and in committees. But their influence would be limited if exercised only at the national level.

Their most important role would be through existing parliamentary oversight and control mechanisms, exercised in plenary and in committees. But their influence would be limited if exercised only at the national level. There is also an opportunity to deepen parliamentary oversight at the regional level as well. This was introduced by the chair’s conclusions at the summit in Poznan in 2019, which envisaged a dialogue in the form of interparliamentary meeting without imposing on the parliaments the modality and content of their inclusion.15 Leaving the parliaments to define their own process for joint meetings was a milestone for parliamentary engagement in the Berlin Process. This idea originated from several of the region’s parliaments and was also reportedly extensively advocated before the meeting by one EU member state, but after the Poznan meeting nothing has been done to elevate international parliamentary exchange within the Berlin Process.

Unfortunately, elections in several countries and the coronavirus pandemic have relegated this plan to a low priority for all of the parliaments in the region. Thus, the 2020 summit in Sofia did not mention a parliamentary dimension. Nevertheless, the important resolutions of the summit could bring parliaments together for joint efforts to give impetus to results-oriented regional cooperation and oversight for the implementation of important projects benefiting citizens across the Western Balkans. In order for each country to be successful, coordination and joint efforts need to be emphasized at all levels. Measurable results and progress toward EU accession are essential accountability standards for success shared across the six countries.

The most recent signs of regional interparliamentary cooperation can be found in the Joint Declaration of the European Parliament and the Western Balkans Speakers’ Summit in January 2020 as well as in the Joint Declaration of the European Parliament and the Western Balkans Speaker’s Summit in June 2021. There was a strong and clear message on the critical role of parliaments in advancing the EU reform agenda and delivering on the aspirations of the people, while ensuring the sustainability of a EU perspective for the region and making the process more democratic, more transparent, and closer to the citizenry and civil society, all on the basis of the rule of law. The latest Joint Declarations reinforced the commitment to a parliamentary dimension within the enlargement process.

Conclusion and Recommendations

There is a clear discrepancy and inconsistency between the practice of parliamentary diplomacy in the Western Balkans for the Berlin Process and for other regional or international initiatives. In order for parliamentary diplomacy to become an effective element of the Berlin Process as well, the legislative branch must meet certain requirements.

Effective parliamentary diplomacy requires strong parliaments. That is the first and basic precondition. It is the cornerstone of the crucial parliamentary function of oversight and control. While parliamentary diplomacy and parliamentary oversight are normally considered separately, a parliament’s ability to implement both simultaneously and synergistically would reinforce its position in general. The Western Balkan states need steps toward building resilient institutions and resilient parliaments.

Strong parliaments are achievable through the strengthened offices and parliamentary service of their members. Directly elected by the people, endowed with the duties of representation and decision making, as well as holding any additional constitutional authority given them, parliamentarians need to further develop their real potential and power—especially in international activities where a huge potential is currently squandered. As an autonomous and separate branch of government, legislatures are able to act on their own to express a state’s political will, or more specifically its parliamentary will. Particularly if there is a political backbone at the executive level for some initiative, as it is the case with the Berlin Process, the absence of the parliamentary determination can indicate weak parliamentary will or resolution. This is why it is necessary to raise awareness but also to motivate parliamentarians in the region to seek out new initiatives and to follow more closely the executive’s foreign policy and EU accession agenda.

No less important is the regional ownership of any initiative that governs issues relevant for shaping the future of the Western Balkans. Regardless of the fact that EU accession is a process guided by Brussels and the member states, a regional approach and expanded regional initiative would add value by demonstrating the region’s proactivity, and enthusiasm. Most importantly it could originate from the people themselves, as represented by their national representatives in the parliaments.

One concrete proposal for such an idea would be that, under the framework of the Berlin Process, regular interparliamentary conferences bring together the foreign affairs committees from each of the six countries’ parliaments to contribute to the progress in the integration agenda, thereby speeding up the overall process. As conference topics expand to include infrastructure and economic development, for example, this would likewise expand the scope for other parliamentary committees to be involved. Parliamentary working bodies have the potential to launch such an important regional dialogue and to perform critical democratic review and control functions, providing oversight over the implementation of the result-oriented Berlin Process arrangements. One possibility is to integrate parliamentary gatherings into Berlin Process summits, following the high-level meetings of heads of states and governments and ministerial-level ones. Whatever it may eventually look like, it is long overdue that parliaments and parliamentarians had a seat at this table.

Dijana Mitrović is a parliamentary adviser dealing with foreign affairs and diaspora affairs in the Committee on International Relations and Emigrants of the Parliament of Montenegro. As an adviser in the parliamentary service, she has experience in the field of parliamentary diplomacy at the level of the president, the vice president, and the committee level. She is a graduate in political science and international politics of the University of Belgrade.

- 1Péter Bajtay, Shaping and controlling foreign policy - Parliamentary diplomacy and oversight, and the role of the European Parliament, July 2015; Stelios Stavridis and Davor Jancic, “Introduction: The Rise of Parliamentary Diplomacy in International Politics,” The Hague Journal of Diplomacy, 11, 2016.

- 2Geert Jan Hamilton, Parliamentary diplomacy: diplomacy with a democratic mandate, Association of Secretaries General of Parliaments, October 2012.

- 3Inter-parliamentary Union, Parliament and democracy in the twenty-first century: A guide to good practice, 2006.

- 4George Noulas, “The Role of Parliamentary Diplomacy in Foreign Policy,” Foreign Policy Journal, October 22, 2011.

- 5Inter-parliamentary Union, Parliament and democracy in the twenty-first century.

- 6Ibid.

- 7There is such a multilateral group in Bosnia and Herzegovina. The country’s parliament has a Group of Friendship to Neighboring Countries that is responsible for establishing contacts and cooperation with representatives of the parliaments of Croatia, Slovenia, Italy, Malta, Serbia, Montenegro, Greece, Cyprus, Macedonia, Albania, Hungary, and Austria.

- 8Ibid.

- 9Parliament of Montenegro, Cetinje Parliamentary Forum (CPF), undated.

- 10National Assembly of the Republic of Serbia, Activities in the area of regional cooperation, undated; Regional Cooperation Council, RCC and Regional Initiatives and Task Forces in South East Europe, undated.

- 11Austria, Bulgaria, Croatia, France, Germany, Greece, Italy, Poland, Slovenia, and until Brexit the United Kingdom. Other participants are the European Commission, the European External Action Service, the EU presidency, the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, and the European Investment Bank.

- 12Final Declaration by the Chair of the Conference on the Western Balkans, November, 2017.

- 13European Commission, An Economic and Investment Plan for the Western Balkans, October 6, 2020.

- 14Ibid., pp. 17-19.

- 15Western Balkans Summit Poznań, “Chair’s conclusions,” July 5, 2019.

About the ReThink.CEE Fellowship

As Central and Eastern Europe faces mounting challenges to its democracy, security, and prosperity, fresh intellectual and practical impulses are urgently needed in the region and in the West broadly. For this reason, GMF established the ReThink.CEE Fellowship that supports next-generation policy analysts and civic activists from this critical part of Europe. Through conducting and presenting an original piece of policy research, fellows contribute to better understanding of regional dynamics and to effective policy responses by the transatlantic community.