Responsibility, Accountability, and Participation: Toward Good Governance in Armenia, Georgia, and Ukraine

For the past three decades, most countries in the wider Black Sea region have worked toward reforming their political, social, and economic governance systems. One of the biggest obstacles these countries have faced in this reform process is corruption. Transparency International’s Corruption Perception Index, which measures perceived corruption levels worldwide, ranked Ukraine 104th of 180 countries, Armenia 62nd, and Georgia 49th.

Corruption festers in the absence of transparency, accountability, and civic engagement. The legacy of the Soviet system, which was opaque and answerable only to party leaders, is difficult to overcome. Even today, many of the institutional processes that are readily visible in Scandinavian countries (generally ranked as the least corrupt) are hidden from the public in the Black Sea region. Limited transparency results in a lack of stakeholder accountability and civic engagement. As pillars of good governance, transparency, accountability, and civic engagement heavily influence the economic and political landscapes of these countries.

Addressing Corruption: Country Cases

Armenia

The current Armenian government, which came to power in 2018, has expressed its determination to tackle long-standing challenges including systemic corruption, a dearth of transparency and accountability in policymaking, electoral system flaws, and weakened rule of law, as well as to pursue substantial reforms in the judiciary, police, and constitutional domains (Freedom House, 2023). However, Yerevan is dealing with additional challenges arising from the 2020 conflict with Azerbaijan over Nagorno-Karabakh, and the 10-month blockade of the Lachin Corridor (the road linking Nagorno-Karabakh to Armenia) in 2023, with the more than 120,000 people fleeing to Armenia creating a humanitarian crisis.

The government has nevertheless implemented several policies and initiatives to address corruption—notably, its Anti-Corruption Strategy and Action Plan for 2023–2026. Armenian authorities formulated the anti-corruption strategy by first assessing the previous strategy’s execution and then incorporating research from NGOs and international partners. The development process was inclusive and transparent, involving multiple stakeholders including representatives of state administrations, civil society organizations, higher education institutions, international organizations operating in Armenia (for example, Transparency International Anti-Corruption Centre, USAID), business sector representatives, and independent experts. The action plan noted the proliferation of corruption and discussed ways to eradicate the incentives and circumstances that fuel corruption within public administration. It sought to instill virtues such as benevolence, transparency, participation, and efficiency into the system through the establishment and enhancement of viable structures. The strategy involved implementing consistent state regulations designed to thwart corruption through enforcement and introducing an institutional framework dedicated to combating corrupt practices.

The main directions of the action plan are:

- development of the institutional system for the prevention of corruption

- improving mechanisms for preventing corruption and strengthening welfare in the public sector

- continuous improvement of the welfare system

- improvement of legal and institutional systems for combating corruption

- institutional strengthening of anti-corruption courts

- improvement and modernization of the disclosure system

- anti-corruption education and public awareness

- improvement of anti-corruption monitoring and evaluation system

To ensure the effectiveness of the action plan, the implementation of the anti-corruption strategy will remain public, transparent, and innovative and will include the active participation of society. Yerevan will establish a monitoring and evaluation system that will be improved continuously. The system encompasses the Anti-Corruption Policy Council and the Ministry of Justice. Anti-corruption program officers of those bodies supervise the implementation of the action plan.

The Ministry of Justice, which is tasked with formulating, overseeing, and assessing anti-corruption policies, functions as the specialized institutional body within the anti-corruption framework. Key benchmarks for assessing outcomes in the monitoring and evaluation report encompass Transparency International's Corruption Perception Index and the evaluation report from the fifth round of the Istanbul Anti-Corruption Action Program by the Eastern European and Central Asian Anti-Corruption Network of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), titled "Anti-corruption reforms in Armenia" (2023 report, 2026—a minimum increase of 20 points in each performance domain). Overall performance, however, was affected by the coronavirus pandemic and the events in Nagorno-Karabakh mentioned above.

Armenia has implemented laws and regulations to criminalize corruption, including the Law on Combating Corruption and the Law on Public Service. These laws aim to prevent corrupt practices and establish penalties for individuals who engage in them. Armenia has set up specialized anti-corruption agencies such as the Anti-Corruption Committee (established in 2021), the Corruption Prevention Commission, and the Special Investigative Service (SIS), which are responsible for investigating and prosecuting corruption cases.

The country also participates in international collaborative efforts to combat corruption. It is a member of the Group of States against Corruption (GRECO) and of the Open Government Partnership, and has ratified the United Nations Convention against Corruption (UNCAC). These collaborative efforts facilitate the exchange of information, technical assistance, and best practices. In April 2021, the Armenian National Assembly enacted legislation to establish the Anti-Corruption Court, facilitated through modifications to the Constitutional Law "On the Judicial Code." The selection of judges occurred between July 30 and August 8, 2022, followed by the issuance of official seals signifying the initiation of the court's functions. In accordance with Armenia's Judicial Code, the Anti-Corruption Court comprises a minimum of 15 judges, with at least ten specializing in criminal corruption cases and a minimum of five focusing on civil anti-corruption matters.

Armenia now needs to encourage civil society participation in the anti-corruption monitoring process. Civil society should be represented on the country’s Anti-Corruption Council and have a role in independent reporting. Thus far, civil society representatives have attended the meetings, but their numbers should be increased.

However, certain institutional problems and complications remain in the fight against corruption. The traditionally close relationships among Armenian politicians, public servants, and businesspeople have often influenced policymaking and resulted in selective law enforcement. High-ranking officials are rarely subjected to investigations, even when there is clear evidence of abuse of power. Although the government tried to investigate allegations of illegal activity and strengthen anti-corruption measures following the 2018 Velvet Revolution, it faced significant challenges resulting from security issues around the conflict with Azerbaijan. Legislation established an anti-corruption court in April 2021, but the court did not become operational until November 2022. And no charges have been filed despite the launching of investigations into cases involving prominent individuals. In parliament, legislators took significant steps to promote transparency in 2020—such as bolstering asset declaration obligations—but the lack of accountability persists.

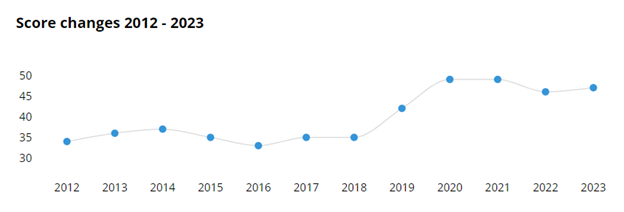

Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) serves as a useful resource for evaluating Armenia’s advances in tackling corruption. For example, in 2023 Armenia’s corruption perception ranking increased by only one from the previous year, which is not terribly significant (see Figure 1.). These results signify that many times reforms are not effective in practice, due to a lack of either political will or resources.

Figure 1. Corruption perception index 2023, Armenia. Source: Transparency International.

In sum, it is crucial to highlight Yerevan’s strong political determination to address a specifically articulated political challenge: the establishment of a public ethos that adamantly rejects corruption within the Republic of Armenia. This is a declared political objective of the current government. During this period (2018-2023), it has undertaken extensive and high-quality work to orient itself toward anti-corruption measures and to generate ideas for the further institutional development of the fight against corruption. However, the anti-corruption battle, the investigations of corruption, and the recovery of the damage caused by corruption are not proceeding on the scale that the public expected. The government explains this in terms of the ongoing conflict in the region and the recent pandemic. In the absence of substantive changes in the immediate future, the government may find it increasingly difficult to rationalize its shortcomings. At the same time, the public, a majority of whom elected the government, may find it increasingly difficult to sustain trust in the administration.

Georgia

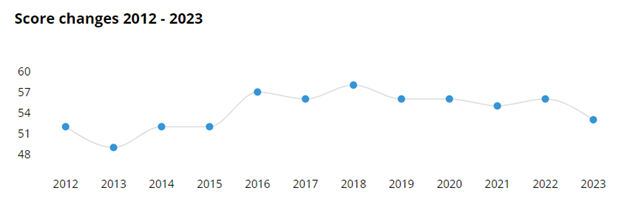

Before the release of Transparency International’s 2023 Corruption Perceptions Index Georgia's CPI ranking was respectable, but a lack of significant improvement over the years was still notable (see Figure 2). The situation took a turn when Georgia's score decreased by three points, settling at 53 out of a maximum of 100. While the country hasn't recorded a score this low since 2015, results raise concerns about the effectiveness of domestic anti-corruption efforts. Even though Georgia leads the Black Sea region, this achievement is attributable primarily to past progress in reducing low-level bribery.

Among 180 countries, based on CPI ranking, Georgia is positioned 49th, alongside Cyprus, Grenada, and Rwanda. In contrast, in 2022, Georgia ranked 41st with a score of 56, alongside the Czech Republic, Italy, and Slovenia.

Figure 2. Corruption perception index 2023, Georgia. Source: Transparency International

The country faces a troubling trend toward increasing high-level corruption and deepening state capture. The current government is associated with the ruling Georgian Dream Party, which is believed to be under the full control of wealthy businessman and former Prime Minister Bidzina Ivanishvili and has contributed to the erosion of anti-corruption efforts. Ivanishvili declared his third entry into Georgian politics in December 2023. State institutions including the judiciary and law enforcement have been compromised, allowing abuses of power at the highest levels to go largely unpunished.

Transparency International Georgia's monitoring has identified numerous cases of alleged high-level corruption that have gone uninvestigated, pointing to a worrisome conclusion that the top levels of government are becoming kleptocratic. In practice, this involves officials systematically using their political influence to exploit the country's resources and undermine dissenting voices, including those of the political opposition, the media, and civil society. Recent defamation campaigns against activists and civil society organizations have raised concerns that the parliament may consider implementing a foreign agent law akin to Russia's to target nonprofit organizations.

In February 2023 the introduction and preliminary approval of the "Foreign Agent" bill, influenced by Russian legislation, marked a low point in a series of anti-democratic actions by the government over the past few years. Members of the parliamentary majority, specifically nine individuals from the "People’s Power" movement (which lacks legal status), proposed the draft laws "On Transparency of Foreign Influence" and "On Registration of Foreign Agents", aiming to express opinions the ruling party tends to avoid. The Georgian Dream Party's leadership, including the former Prime Minister Irakli Garibashvili, supported both pieces of legislation.

Despite the fact that the Georgian government dropped the bill on March 10 after massive demonstrations against the so-called “Russian law”, civil society organization (CSO) members of the Open Government Interagency Coordination Council of Georgia (and OGP Georgia’s Forum) published a letter of concern on April 13, 2023. They emphasized that “openly expressing support for the Russian-style law not only contradicts the desires of the Georgian people and the country’s European and Euro-Atlantic aspirations, which include meeting the 12 EU candidacy recommendations, but it also represents a blatant disregard for the principles enshrined in the Open Government Declaration and Articles of Governance.”

The EU pointed to the government's inaction against high-level corruption as a key concern in its June 2022 decision not to grant Georgia candidate status. The European Commission has outlined a set of 12 priorities that Georgia must fulfill to attain EU candidacy, and taking steps to clean up governance is high on the list. While there are discussions about Russian influence in Georgian politics, including the emergence of pro-Russian political parties, the EU’s decision centered primarily on internal governance issues.

On November 30, 2022, the Georgian parliament amended the “On Conflict of Interest and Corruption in Public Service” law to establish an Anti-Corruption Bureau. This move was prompted by the European Commission’s recommendation to consolidate all critical anti-corruption functions in a single body to enhance autonomy and to provide adequate resources and institutional independence to the newly formed Special Investigative Service and Personal Data Protection Service. Transparency International Georgia concerned that the bill was not entirely compatible with EU standards, called on the parliament to send the law to the Council of Europe’s advisory Venice Commission and the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe’s Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights for assessment. Consequently, in its opinion dated December 15–16, 2023 regarding Georgia’s anti-corruption laws, particularly the amendments made to the Anti-Corruption Law in November 2022, the Venice Commission has stated that: “The current institutional design does not provide for a sufficient degree of independence of the Anti-Corruption Bureau (ACB)”.

At the beginning of January 2024, The Georgian Anti-Corruption Bureau announced its plan to inspect the asset declarations of 300 public officials in 2024, citing significant public interest and the high risk of corruption, according to their press release. The initiative is supported by a special commission that includes civil society representatives, and it targets high-ranking figures like Prime Minister Irakli Garibashvili, Georgian Dream party Chair Irakli Kobakhidze, cabinet members, deputies, MPs, and Tbilisi Mayor Kakha Kaladze. The Bureau will also examine officials from the judiciary, regulatory bodies, and key state enterprises. The selection of declarations for verification was led by an independent commission facilitated by TI-Georgia, which noted a high rate of non-compliance in asset disclosure in past years. This commission, convened for the first time since 2018, includes members from various legal, academic, and transparency organizations.

After extensive discussions among EU and Georgian state and civil society representatives, as well as international bodies about the integrity of the Georgian ruling party, the European Parliament finally adopted the EU-Georgia association agenda for the period 2021–27 in August 2022. In response to the EU’s key points, the government approved a National Action Plan (NAP) for EU Integration in April 2023.

The NAP serves as a comprehensive policy document covering various activities required to fulfill the obligations of the association agenda, specifically those focusing on the fight against corruption and judicial reform. It stresses the significance of ambitious political, judicial, and anti-corruption reforms in advancing Georgia's democratic and rule-of-law goals. These encompass strengthening the powers of investigation of corruption, monitoring the asset declarations of public officials, setting safeguards to prevent conflicts of interest, promoting citizen participation in governance, and enhancing public administration transparency and accountability.

Medium-term priorities include effectively implementing relevant international legal instruments such as the United Nations Convention Against Corruption (UNCAC) and the Council of Europe’s Criminal Law Convention on Corruption and its additional protocol, as well as complying with recommendations from the Group of States Against Corruption (GRECO) and the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development’s (OECD) Anti-Corruption Network. These actions underscore the urgent need for Georgia to address corruption among high-ranking officials and to strengthen its commitment to transparency and accountability. Failure to do so would not only jeopardize the country's standing with international partners but also undermine public trust and hinder progress against graft at all levels of society.

On December 14, 2023, the European Council granted Georgia candidate status, conditional upon the implementation of measures outlined in the Commission's recommendation from November 8, 2023. Specifically, Georgia should, among other actions, “further address the effectiveness and ensure the institutional independence and impartiality of the Anti-Corruption Bureau, the Special Investigative Service, and the Personal Data Protection Service. Address Venice Commission recommendations related to these bodies in an inclusive process. Establish a strong track record in investigating corruption and organized crime cases.”

Ukraine

Ukraine experienced a wave of transformational hope when Volodymyr Zelenskyy, a newcomer to politics, assumed power in 2019 and brought with him a fresh governing team. Simultaneously, the parliament seated many new deputies. Ukrainians and their international partners held out renewed hope for reforms—especially those addressing the judiciary and the economy.

Ukraine’s economy is highly influenced by the financial assistance it receives from external donors and organizations, which amounted to nearly $50 billion annually before the Russian invasion began in 2022. At the same time, the country’s competitiveness is undermined by a shadow economy whose value was estimated at $35 billion in 2021. The state’s official tax revenue is $40 billion. The shadow economy directly influences the political landscape and weakens governance capacity. Consequently, the eradication of corruption remains problematic. According to Transparency International’s 2022 Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI), a scale where 0 represents a perception of high corruption and 100 indicates low perceived corruption levels, Ukraine scored 33 out of 100. The country is thus in need of significantly more effective anti-corruption strategies and reforms.

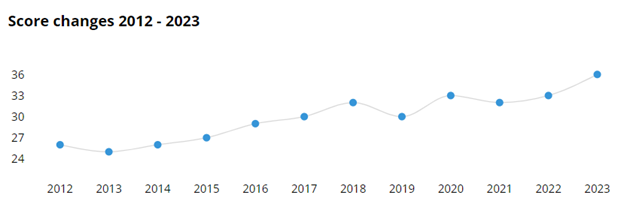

With an overall gain of eight points since 2013, Ukraine has demonstrated consistent action against corruption. However, the country's ranking at 116th of 180 countries points to a persistently high level of perceived corruption in its public sector (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Ukraine still needs to do more to fight corruption. Source: Transparency International 2023

Economic Factors

Ukraine has an agrarian, steel, and trading economy that relies on its heavy metallurgy complex and the world’s demand for grains. In a nutshell, the base of the country's economic structure has been held over from Soviet times. To be fair, new sectors such as IT, property development, and others have evolved and are already playing a noticeable role in the overall goods and services export figures. The biggest and most continuous threats to the development of capitalistic principles and economic freedom in Ukraine remain the outdated legal system, the presence of thousands of old-school bureaucrats, and law enforcement’s excessive control. Before the full-scale Russian invasion, the Ukrainian GDP was $200 billion and the economy was growing at the rate of 3.45%. After the Russian invasion, GDP dropped rapidly to $157 billion. The overall economy shrank by 50% in 2022, and the national currency was devalued by 25% in the first quarter of that year. Russia’s blockade of the Black Sea severely hindered exports. Yet, despite the seriousness of these economic challenges, the main obstacles to change are the political and institutional systems that limit Ukraine’s economic capacity.

Political Factors

The political landscape in Ukraine has always been transactional in nature. Transactionalism endures across multiple political systems—from socialism to capitalism, from pro-Russian narratives to pro-Western ones, and from Soviet bureaucracy to European efficiency. No single issue explains the complexity of the Ukrainian political landscape. On the one hand, the level of social involvement in political processes was never high. Quite often, the public demand was for quick fixes, and this defined the political and strategic agenda for decades. On the other hand, the absence of a complex political vision for Ukraine, together with complicated governance and constant political challenges, led to a landscape of half-measures and an incentive to maintain the status quo.

Governance

Ukraine remains overloaded with institutions and state companies. Ukraine’s government consists of 107 institutions, 170,000 workers, and 3,600 state-owned enterprises managed by 96 government bodies. The current excess of government entities is a direct legacy of the Soviet governance machine. No system of governance can efficiently operate so many enterprises and institutions. The obvious consequences of such a bloated government system are high corruption rates, resistance to the implementation of new policies, and a high level of power for local elites. As a result, Ukraine’s competitiveness was artificially slowed (55.73 in 2011 compared to 56.99 in 2019), yet shadow markets grew to 35 billion USD in 2020. Ukraine remains under the influence of oligarchs who exploit unfair market conditions and influence the political and governance process to receive ultra-high profits and undue governmental support. Even though the influence of the oligarch is not as great as it has been at times throughout the modern history of Ukraine, there are two important factors to consider. First, the oligarchy in Ukraine has diversified. Oligarchs have begun to use a whole range of IT and energy assets as well as philanthropic endeavors to whitewash their reputations. Second, by creating unfair market conditions and pushing international investors out of Ukraine, they remain among the biggest investors. This puts them in a strong negotiating position with the government.

This disproportionate growth between the shadow economy and the official one has created an ecosystem of social relationships in Ukraine in which legal business and government bodies struggle to develop a consistent dialogue on the future of the business landscape in the country. Nevertheless, it is worth mentioning that Ukrainian businesses have already managed to incorporate some of the world’s best corporate governance principles and are more than ready to support the government of Ukraine in developing transparent and efficient inter-state governance.

Anti-Corruption Measures

Throughout its independence, Ukraine has developed and implemented new anti-corruption measures. Western partners—the European Commission, the US Government, the IMF, and the World Bank—consistently provide Ukraine with the aid it needs to minimize the chances of corruption and money laundering. Since 2014 and the changes brought by the Maidan, it has been widely understood that the cornerstone of a corruption-free Ukrainian future is high-quality judicial reform and the new generation of law enforcement institutions that make use of some of the best investigation practices of its European and US counterparts.

Anticorruption reforms led to the wide-ranging judicial reform that was launched in 2014 and included changes to the constitution and laws of Ukraine. The overall aim was to depoliticize the process of selecting judges by introducing new vetting processes. The judicial reform showed progress in its early years, but it is not yet complete. The complexity of the legal system and the resistance of the previous law enforcement elites, along with the extreme wartime conditions in Ukraine, slowed the progress of the reform. Yet, considering Ukraine's ambition to become an EU member, this reform will remain one of the most significant markers of the country’s political maturity.

Since 2014, several specialized law enforcement institutions have been created with the aim of strengthening anti-corruption efforts and eliminating economic crimes. The National Anti-Corruption Bureau of Ukraine (NABU) was created in 2014, the State Bureau of Investigation (SBI) in 2016, and the Economic Security Bureau (ESBU) in 2021. While there has been significant progress in investigations, the work of these bureaus will not be complete until the judicial reform functions as intended—with a fair legal approach and unbiased judges.

One positive development is the Ukrainian government’s effort to eliminate excessive bureaucracy. Decentralization efforts and initiatives such as the Diia mobile phone app that connects 19 million Ukrainians with more than 120 government services have reduced the potential for graft by streamlining state services.

War, Mobilization, and Threats to Ukraine’s Institutional Capacity

War is first of all a stress test for a country's infrastructure. Second, war catalyzes social tension and increases social inequalities. Third, war always centralizes power. Finally, war means a lack of resources. All these characteristics are present in wartime Ukraine. By November 2023, Ukraine had received $230 billion in aid from its partners and allies. This was enough to sustain Ukraine, but for victory and reconstruction, hundreds of billions more are needed.

At the same time, Ukraine must carry on with the most difficult social and institutional process it has undertaken since its independence: mobilization. More than eight million people fled Ukraine over the course of 2022 and 2023. One million are serving in the Armed Forces of Ukraine, but according to the General Staff of the Armed Forces, at least 500,000 more must be mobilized. For all the challenges mentioned, the quality of governance plays a key role in sustaining the country not only during the war but also through its subsequent rebuilding process. Without the proper processes, procedures, and mechanisms, the rebuilding of Ukraine cannot be efficient. Despite the wartime conditions, Western partners continue to advocate for reform implementation that includes proper governance. While it faces one of the greatest challenges in its history, Ukraine also has a chance to make drastic changes that will shape the next decades of its future and that of the whole region.

Recommendations

Developing effective measures to tackle corruption is essential for the advancement of good governance and social stability among Black Sea nations. Because countries differ in their institutional structures, cultures, geopolitical situations, and degrees of political will and civic mobilization, there is no single formula for success. Still, some universal policies and procedures can be effective in discouraging corruption, promoting transparency and accountability, and fostering civic engagement.

The Fight Against Corruption

- Strengthen legal frameworks. Enhance and enforce anti-corruption laws, regulations, and policies that cover the public and private sectors. Clearly define guidelines for reporting, investigating, and prosecuting corruption cases.

- Promote an independent judiciary and law enforcement. Establish an impartial and independent judicial system and strengthen law enforcement agencies. Provide adequate resources, training, and autonomy to enable them to investigate and prosecute corruption cases without interference.

- Conduct corruption risk assessments and take action to address the problems identified and to fill gaps in legislation. Self-assessment mechanisms and participatory processes can be used for this purpose, engaging all interested parties in the field and creating transparency and accountability mechanisms at all levels of governance.

- Create mechanisms for regular monitoring and evaluation. This involves setting up systems and processes that use indicators and benchmarks to track progress, identify flaws, and make necessary adjustments to strategies. The information gathered serves as a valuable feedback loop, allowing policymakers to make informed decisions and refine anti-corruption efforts.

- Stress ethical behavior and integrity. Implement ethics training and awareness programs for public servants, emphasizing the importance of conflict-of-interest avoidance and of decision-making guided by the best interests of the polity.

Transparency and Accountability

- Encourage transparency and accountability in public administration and procurement and decision-making processes. Enhance disclosure mechanisms such as requiring public officials to make financial disclosures and guaranteeing public access to guidelines, regulations, and financial documentation. Adopt efficient monitoring and auditing systems to prevent misappropriation and track the use of public funds.

- Enforce mandatory asset disclosures for public officials, rigorous financial audits, and regulations addressing conflicts of interest. Instill a culture of reporting and investigating corruption cases and ensure that individuals involved face appropriate consequences.

- Delineate clear and explicit roles, responsibilities, and performance expectations for government officials and employees. This clarity facilitates accountability.

- Introduce performance evaluation systems that gauge the effectiveness and efficiency of government institutions, ensuring that merit and performance rather than political affiliations or personal connections determine employee recognition and advancement.

Civic Engagement

- Support civil society organizations, independent media, and investigative journalism. Encourage their involvement in monitoring government activities, exposing corruption, and advocating for reforms. Ensure NGO representation in anti-corruption bodies and policy discussions.

- Implement ethics, integrity, and anti-corruption education at all levels of society, including institutions of higher learning and in professional training, to raise awareness of corruption’s corrosive impact and the benefits of building a society free of it.

- Safeguard a culture of whistleblowing, supporting individuals who expose corruption. Develop systems to protect them, maintaining secure and confidential reporting channels. Implement legal measures to shield them from retaliation.

- Encourage anti-corruption cooperation at the regional level and beyond. This entails information-sharing, best-practice exchange, international collaboration on investigations and prosecutions, and participation in global initiatives such as UNCAC.

- The successful implementation of these recommendations requires political dedication, continuous efforts to entrench the rule of law and to nurture an ethos of impartiality and transparency, and coordination among governments, civil society, and international partners. By adopting such a comprehensive approach, countries in the Black Sea region can make significant strides in fighting corruption and promoting good governance.

Meline Avagyan, Ani Tsintsadze and Kostiantyn Turchak are 2023 GMF Policy Designers Network (PDN) fellows. This article is part of a series of contributions from PDN fellows. The PDN is made possible by a grant from the German government through the KfW development bank.