Toward a New Youth Brain-drain Paradigm in the Western Balkans

Summary

Youth brain drain is one of the most worrisome problems for the Western Balkan Six countries (WB6)—Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Kosovo, and Serbia. The pace and intensity of youth brain drain, rank the WB6 among the top brain drain leaders in the world, with estimations to lose a quarter to half of its skilled and educated young citizens in the forthcoming decades. A situation that cast serious doubts on the democratic and economic progress of WB6, and their prospective membership into the EU.

Youth brain drain is a historically rooted topic in the culture and tradition of the WB6, provoking huge sentiments and heated public debates. Due to its sensitivity, it is prone to politicization and misuse by the political parties that did not manage to find a compromise for its full acknowledgment as a separate policy field. Therefore, to date, the policy approach to youth brain drain is declarative and inconsistent, tackled as part of bigger policy areas such as youth employment, education, and diaspora engagement. Although formally, all WB6 countries have policies and institutional mechanisms in place, youth emigration and the desire to leave are constantly on the rise, underlining their limited scope and impact to keep youth home.

This paper analyzes the conceptual shortcomings of the current policy approach. In line with the latest trends and tendencies of youth brain drain, it offers fresh policy options for utilization of the potential of the regional youth diaspora as the new WB6 development doctrine. The paper sees the youth diaspora not only as a source of remittances but also as a source of investments, know-how, skills, and connections as per the examples of several EU member states. The paper further announces the necessary paradigm change grounded in the shift of the public narrative and redesign of return and circulation policies through deepening regional cooperation and establishing a new migration deal with the EU under the framework of the WB6 accession processes.

Introduction

The Western Balkan Six countries (WB6)—Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Kosovo, and Serbia—are rapidly losing their population. In the last three decades, due to massive emigration, Serbia has lost 9 percent of its citizens, North Macedonia 10 percent, Bosnia and Herzegovina 24 percent, and Albania 37 percent. These are mostly young, educated, and skilled people who decided to leave their country due to poor democratic and economic conditions and low quality of life. On a global scale, the WB6 rank among the countries most affected by brain drain. It is expected that the region will lose around 1 million youth in the forthcoming decade, worsening the already serious repercussions for democratic and economic prosperity and the future of the region.1

As a historically rooted and sensitive topic, in the WB6 youth brain drain is often politicized and influenced by the political situation in each country. Consequently, thus far, these countries’ governments have not properly recognized and tackled the problem at the political or policy level. Youth brain drain is mentioned as a top priority during election campaigns, but it remains neglected. It is an issue characterized by inconsistent, inefficient policies and surrounded by a negative public narrative.

Considering the current state of affairs, the scale of already lost youth human capital, and the youth emigration tendencies in the WB6, this paper explores policy options to turn the migration paradigm on its head and to capitalize on the potential of the youth diaspora. It offers alternatives for changing the youth brain-drain paradigm in connection to the EU integration process and to regional cooperation at this particular moment in the WB6 relations. Posing the issue alongside other difficult questions for the WB6, the paper recommends the adoption of tailor-made circulation and return policies that can lead to the utilization of the finances, skills, and knowledge of youth as the new development paradigm for the region.

This paper looks at this issue based on an analysis of the national, regional, and international legislation, policies, and practices addressing the brain-drain issue in Central and Eastern Europe and the EU. As well as analyzing key policy documents, existing research, and reliable statistical sources, the research relied on ten interviews with representatives from regional governmental organizations, government officials, and civil society experts.

The first section gives an overview of youth emigration trends and brain drain in the WB6, their scope, and their negative impact. The second section analyzes the current policy constellation in the six countries, noting the impact of national and regional policies and institutions on youth brain drain. The third section elaborates on policy options, drawing on the previous analysis and comparative practices in line with the current EU-WB6 relations.

Youth Brain Drain

The WB6 have a rich modern history of emigration. After the Second World War, they experienced three significant waves. The first was in the early 1960s as a consequence of the high levels of unemployment in Yugoslavia and the open migration policies of European countries.2 By the mid-1970s, around 1.1 million relatively young and low-skilled workers had left Yugoslavia, primarily for Germany, changing public attitudes toward emigration in Yugoslavia and forming vast diaspora communities.3 The resulting migratory networks were enlarged with the second wave of forced emigration in the 1990s caused by the violent dissolution of Yugoslavia. They were further intensified after 2010 with the third and ongoing wave that has been motivated by the region’s troubled economic and democratic transition and the global financial crisis, as well as by favorable EU migration policies, including visa liberalization for the WB6.

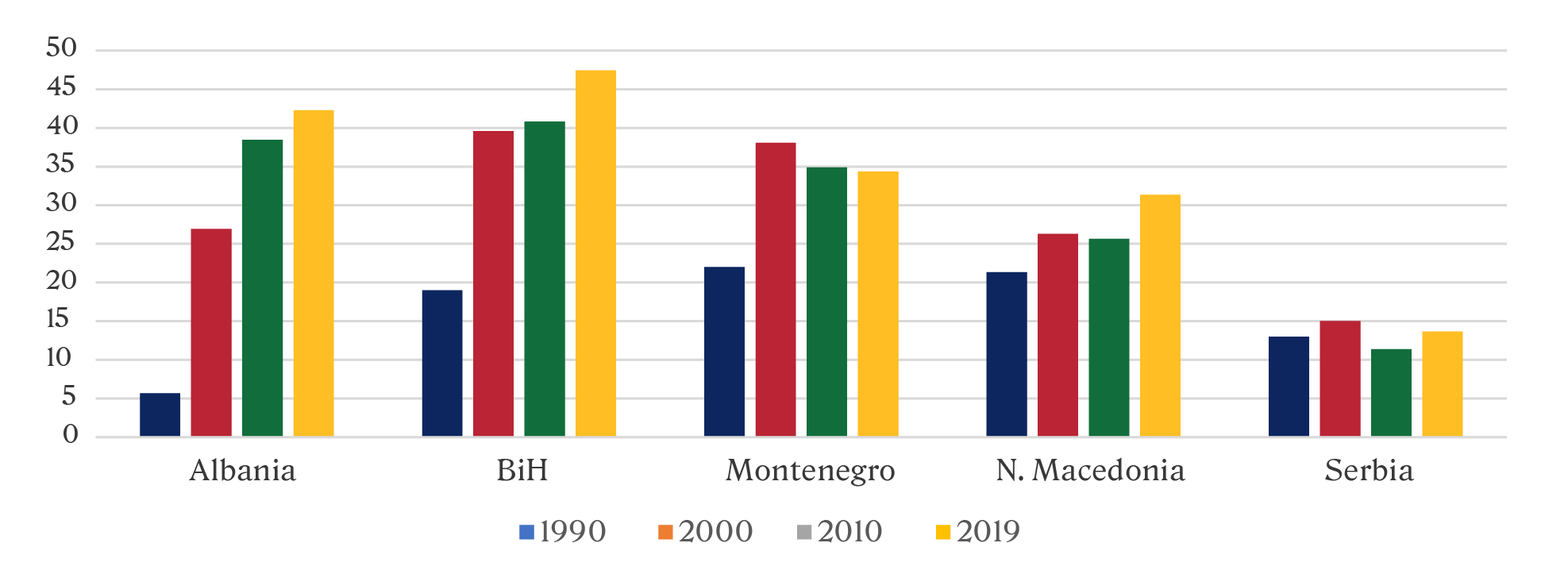

Massive emigration coupled with some of the lowest fertility rates in the world contribute to a sharp population decline in the WB6, with the countries increasingly displaying aging and shrinking demographics.4 Since 1990, the WB6 (except Montenegro) have seen their population drop—by 9 percent in Serbia,5 10 percent in North Macedonia, 24 percent in Bosnia and Herzegovina, and 37 percent in Albania.6 The number of emigrants from the WB6 has doubled over this period, reaching 4.6 million in 2019. The size of the emigrant population for the WB6 was equivalent to between 30 percent and 45 percent of the resident population, except in the case of Serbia where it was 14 percent (Figure 1).7

Figure 1: Emigrant Population as Percentage of Resident Population, 1990-2019

Young, educated, and skilled people are at the forefront of emigration from the WB6. Recent labor-market reports and international studies show that the WB6 struggle to keep such citizens.8 The 2019 Global Competitiveness Index ranks the region among the world’s leaders in brain drain, lagging far behind in the competition for youth talent.9 A 2021 study by the Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies (WWIW) found that all the WB6 experienced net emigration of young people at all levels of educational attainment between 2010 and 2019, with variation among the countries in terms of magnitude and age patterns. For example, Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Kosovo experienced substantial net emigration of the highly educated—that is, brain drain. But almost 40 percent of the young emigrants from Albania were highly educated, compared to around 6 percent of those from Bosnia and Herzegovina.10 The WWIW study also indicates there was net immigration and brain gain in Montenegro, North Macedonia, and Serbia. However, it also lists several factors that cast doubt on the accuracy of the latter data, such as the scarcity of national data on migration, the temporality of net immigration, and the lack of qualitative evidence of the permanent nature of immigration.11

The push factors for youth brain drain in the WB6 are quite diverse. The question of moving abroad is highly individual, depending on personal and societal characteristics such as education level, geographical area of origin, or employment and financial status. Therefore, there are differences across the WB6 regarding the profile of youth desiring to emigrate. However, the prevalent push factors are as would be expected, considering the unfavorable political and socioeconomic marginalization of youth in the six countries. Youth suffer from high unemployment, poverty, and exclusion—especially those from minorities; those not in employment, education, or training (NEET); those in rural areas; and young women.12

Moreover, the WB6 remain among the poorest countries in Europe, with notably lower living standards and GDP per capita than the EU members. Before the coronavirus pandemic, it was estimated that, with an average per capita income growth of around 3 percent, it would have taken the WB6 about 60 years to reach the average income level in the EU. The pandemic worsened already slow growth prospects and led to significant job losses and welfare cuts halting a decade of progress in incomes and reducing poverty.13

The most recent research shows there is diminishing discrepancy and distinction between the economic and non-economic push factors for youth emigration from the WB6.14 According to the Friedrich Ebert Foundation, around 50 percent of youth want to leave these countries to improve their quality of life, which incorporates economic and non-economic factors. If historically youth predominantly left the region for bigger salaries and better jobs, nowadays they are increasingly leaving for a higher quality of public services, education, healthcare, good governance, or environment. At the same time, financial motives remain crucial with one-third of youth wanting to leave for purely economic reasons, while 10 percent want to emigrate to pursue a better education.15

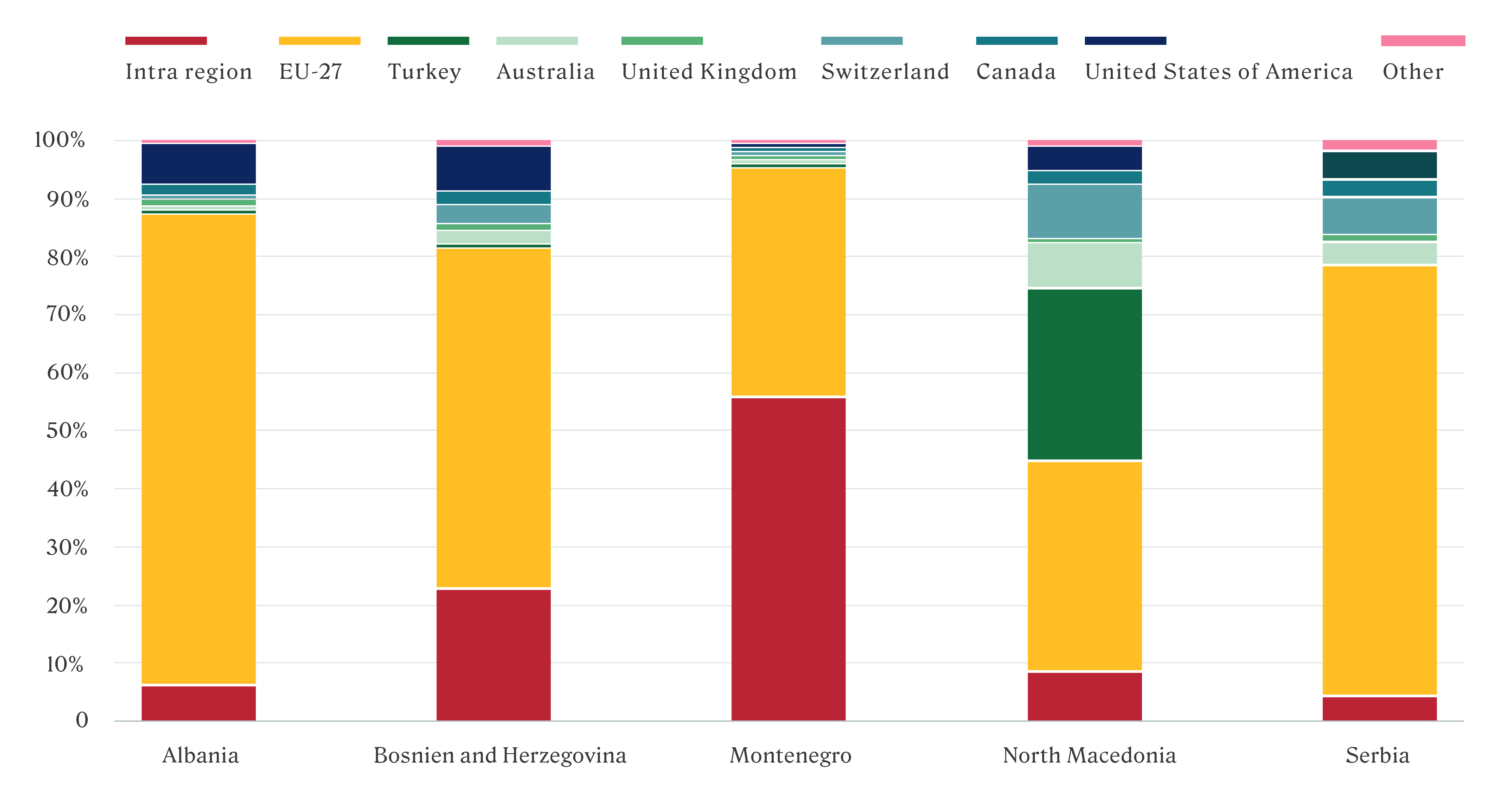

The most important pull factor is liberal EU migration policies. Due to geographical proximity and ongoing membership accession processes, the EU is the most desirable destination for WB6 citizens. At present, more than half of the WB6 diaspora resides in the EU.16 Between 2014 and 2019, the number of first residence permits for WB6 citizens issued in the EU increased from 577,514 to 974,499.17 The total in the last decade was more than 1.5 million, with family reunification, employment, and education as the most common legal grounds.18 Visa liberalization (except for Kosovo) was also a strong impetus for youth brain drain, accelerating travel, educational opportunities, and the creation of social networks (Figure 2).19

Figure 2: Main Destination Countries of Emigrants, 2019

Some EU member states go a step further in welcoming highly skilled WB6 immigrants. The most notable example is Germany, which in the last five years introduced the Western Balkans Regulation and a Skilled Immigration Act aiming to facilitate labor-market entry and the employment of highly qualified professionals.20 Germany has also recently signed bilateral agreements with Bosnia and Herzegovina and Kosovo for the easy employment of healthcare professionals, drastically increasing the youth medical brain drain from these countries. Contrary to the guest-worker agreements signed with Yugoslavia in earlier times, these do not include any clause for the workers’ return after their temporary work in Germany.21 There are similar bilateral agreements between the WB6 and, for example, Croatia, Italy, and Slovenia (or outside the EU with Qatar) in the fields of healthcare, construction, and tourism that contribute to the emigration of youth.

Equally concerning is the desire to leave of those youth still in the WB6. In the Friedrich Ebert Foundation study, 33 percent of them expressed a strong or very strong desire to emigrate—26 percent in Montenegro, 27 percent in Bosnia and Herzegovina, 30 percent in Serbia, 34 percent in Kosovo, 35 percent in North Macedonia, and 43 percent in Albania.22 As with the WWIW study, the Friedrich Ebert Foundation found that the WB6 vary in terms of this brain drain risk. In Albania and Montenegro, it is the highly skilled and educated youth who are keenest to leave, which is also the case to a lesser extent in Serbia, while in North Macedonia it is the less educated youth who are. The percentage of youth with tertiary education who say they want to emigrate is almost one-third of the whole youth population.23

The Friedrich Ebert Foundation has created an Emigration Potential Index that reveals that nearly 1 million young people are likely to leave the WB6 over the next ten years.24 This backs the findings of Gallup’s Potential Net Migration Index from 2017 in which the WB6 (except Montenegro) had negative brain-drain scores (net change in highly educated and skilled citizens), ranging from -27 percent in Serbia to -50 percent in Albania, and negative youth emigration scores (net change in youth population), ranging from -25 percent in Albania to -57 percent in Bosnia and Herzegovina.25

The repercussions of youth brain drain are major. From an economic perspective, higher-quality human capital leads to a higher level of GDP and economic health, and vice versa. Currently, the WB6 are losing human capital and GDP as a consequence of youth brain drain. Probably the most direct cost for their societies is the loss of their investment in education. According to the Westminster Foundation for Democracy, the annual education costs lost as a result of young people leaving the region vary from €840 million to €2.46 billion. This implies a decrease in consumption and welfare for the WB6 economies that costs them around €3 billion of yearly GDP growth.26

The massive outflow of people in certain professions exacerbates the problems related to the availability and accessibility of basic services.

The massive outflow of people in certain professions exacerbates the problems related to the availability and accessibility of basic services. The most critical sector is public healthcare with a huge portion of young doctors and nurses leaving the WB6. Lack of services is also evident in lower-skilled professions such as repair, maintenance, and construction, leading to higher service costs and lower quality.27 An extended brain drain in these sectors will only deteriorate the existing labor-market disparities and lead to higher unemployment and lower quality of life. Thus, brain drain further exacerbates the local problems that drive people to leave, and decreases the motivation of those who stay, making the region a less attractive place to live in.28

Since 2012, the working-age population of the WB6 (not including Kosovo) decreased by about 762,000 or 6 percent. This affects each country differently—Bosnia and Herzegovina had the biggest working-age population decline with -20 percent, followed by Serbia with -10 percent, Albania with -8.8 percent, Montenegro with -3.1 percent, and North Macedonia with -1.4 percent.29 With this pace of depopulation and with current migration policies, it is estimated that by 2050 the WB6 will lose around 15 percent of their population, affecting largely young and educated citizens.30

At the level of politics, brain drain leads to a breeding ground for populism and anti-migrant sentiments that can hurt the fragile WB6 democracies. As seen across Europe, right-wing parties are mobilizing support with alarmist rhetoric about the demographic disappearance of countries.31 Democratic backsliding in the Western Balkans is connected with such populist tendencies.32 For instance, the Fourth Budapest Demographic Summit held in September 2021 was attended by many right-wing leaders from Central and Eastern Europe, who pointed to the EU as the main culprit for the shrinking of the region’s population. Such political platforms negatively influence citizens’ support for the EU and strengthen the anti-democratic and anti-reform agenda in the WB6.

Too Little to Keep Youth Home

Youth emigration and brain drain are sensitive topics deeply rooted in the tradition and collective memory of the WB6, making them prone to politicization and misuse by political actors. Recently, both have gained particular attention in the public discourse as a result of the abovementioned depopulation forecasts and the unfavorable situation of the six countries in terms of demographic, educational, and social capital.33

Youth brain drain is particularly emphasized since the stakes are highest when it comes to losing the young and bright.

Positioned as essential for the survival and prosperity of the countries, youth emigration and brain drain are one of the central topics during elections, around which whole political platforms are built. Parties try to appeal to voters by claiming their many promises and various policy proposals for how to “keep youth home” to be their top priority. Youth brain drain is particularly emphasized since the stakes are highest when it comes to losing the young and bright. This was seen in the last parliamentary elections in Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and North Macedonia, where the politicization of the problem was on display. The biggest parties blamed each other, putting forward numbers about their alleged share of responsibility for the talent exodus. This was picked up by the media and civil society, with headline stories and daunting scenarios of youth emigration.

These public narratives have a negative spillover effect on policy. The region’s policymakers have long neglected the problem, oversimplifying it and not recognizing it as a separate policy area. In time, brain drain became a Gordian knot for the WB6 governments, which have attempted to solve it by a mix of the “Six Rs” menu policy responses to high-skilled emigration.34 In all six countries, retention policies are mostly used to keep youth home and to address the causes of brain drain. Return and resource policies to attract youth back home and to facilitate the management of migration—that is, brain gain and brain circulation—are less used. Moreover, some countries such as Montenegro and Serbia have formulated recruitment policies, targeting foreign students and skilled immigrants from the WB6, as well as from China, Russia, Turkey, and Ukraine.35

Retention

The retention policies of the WB6 are directed to unemployment as the most salient problem for youth. A proliferation of youth-employment policies have been labeled as revolutionary brain-drain actions. Governments particularly focus on active labor-market measures for youth from vulnerable groups and on support for youth entrepreneurship and business employment such as grants, subsidies, internships, reskilling, and upskilling. Montenegro, North Macedonia, and Serbia have introduced dual education systems36 similar to the Swiss model, while North Macedonia piloted the EU’s Youth Guarantee in 2018, which is currently in the preparatory phase in Albania and Serbia as well.37

These policy measures (alongside the massive youth emigration) managed to decrease youth unemployment in the region to a historic low, but it remains nonetheless alarming high at around 30 percent.38 The coronavirus pandemic further increased youth unemployment and rates. For instance, youth unemployment varies from around 32 percent in Serbia to almost 50 percent in Kosovo, while the regional NEET rate is 24 percent.39 Beyond unemployment, particularly long-term, other related issues such as low wages, in-work poverty, precarious working conditions, job insecurity, informal employment, and poor career prospects remain unresolved.40

The reasons behind the limited impact of youth employment as the key retention policy to combat brain drain can be first found in the inadequate investment in active labor-market measures and education.

The reasons behind the limited impact of youth employment as the key retention policy to combat brain drain can be first found in the inadequate investment in active labor-market measures and education. Considering the scope and complexity of the problem, the WB6 do not invest adequately to target all critical labor-market segments. Investments in public education are also scarce while educational policies are not focused on the skills required by the modern and technological labor markets.41 Insufficiently diversified policies with low outreach to those in the NEET category are failing their purpose. This was especially seen in the case of the Youth Guarantee in North Macedonia, where the impact on the youth NEET population was minimal.42 The human resources and technical capacities of the public employment services are especially limited; as the main institutions involved, these are characterized by inconsistency, lack of transparency, and poor cross-sectoral coordination.43

Return and Resource

The first systematic return and resource policies in the WB6 were introduced around 2010 as part of efforts for diaspora engagement. Some consider this new approach based on the nexus between diaspora and development a major political innovation, based on a large consensus between governments, institutions, and civil society. Others see it only as a new development mantra after the diminishing hopes for development through the privatizations and foreign direct investments (FDI).44 In the last decade, the WB6 have adopted key legislation and strategic documents related to this, and they have introduced new institutions and mechanisms for diaspora engagement. With slight differences, these policies in all six countries target the financial potential of the diaspora and tend to facilitate the transition from remittances to investments.

Albania has adopted a National Strategy on Migration Governance and a National Strategy of Diaspora 2018–2024. In Bosnia and Herzegovina, a Policy on Cooperation with Diaspora was adopted in 2017. North Macedonia adopted its first tailor-made Brain Drain Strategy in 2013 and two resolutions on migration in 2015 and 2017. Serbia in 2011 announced a Strategy for diaspora and in 2020 an Economic Migration Strategy 2021–2027 to support return and circular migration. Kosovo adopted Law on Diaspora in 2011 and a Strategy for Diaspora 2014–2017 with a focus on combating irregular migration to the EU. Montenegro adopted a 2017–2020 Strategy for Integrated Migration Management and a Law on Cooperation with Diaspora in 2018.45

These documents envision the creation of modern governance and varieties of institutions and bodies such as Ministries for Diaspora, State Commissions, Offices for Economic Cooperation, Diaspora Centers, Councils for Diaspora, and even an Agency for Circular Migration (in Serbia). The documents also contain policy measures to mainly attract diaspora investments; to promote circular migration and the return of skilled diaspora members; to connect the diasporas; and to create new financial instruments for support to diaspora investment (in the form of Diaspora Development Funds, Diaspora Banks, or Diaspora Business Unions).46

Despite being portrayed as a political priority, youth are not considered a separate policy category and thus their return and circulation are targeted with identical measures as the ones for the rest of the diaspora members.

However, specific youth brain gain and brain circulation policies remain scarce and sporadic. They are only a fragment of the prevalent migration programs, aiming to strengthen cooperation and communication with the diaspora and attract remittances, skills, and investments. Despite being portrayed as a political priority, youth are not considered a separate policy category and thus their return and circulation are targeted with identical measures as the ones for the rest of the diaspora members.47 The reasons for this are manifold.

First, diasporas are a sensitive topic in the WB6 since the countries’ domestic political, ethnic, and religious divisions are exported into the respective communities abroad.48 Hence, the longevity and consistency of the above policies and institutions are dependent on the political landscape in each of the countries. For instance, in Bosnia and Herzegovina, the diaspora policies were adopted after many years more as a political compromise than a wanted policy. In North Macedonia, the post of minister for diaspora was scrapped after the 2020 elections as a political compromise, and merging and redistributing diaspora institutions and competencies is a regular practice in Kosovo and Serbia.

The policies are drafted more as declarative rather than deliberative and realistic documents. They can be seen as wish lists and policy agendas that are overly ambitious considering the capacity of the six states.49 This can be also seen in their proliferation, with in the last decade each country adopting several laws, strategies, and resolutions on the diaspora and migration. In some cases, the policies are not backed up with appropriate financial resources, as in Albania and North Macedonia.

Monitoring and assessment of the implementation and impact of diaspora policies are likewise absent.

There is also an institutional deficit and insufficient staff with the knowledge and experience to carry out complex policy programs. The limited capacities of the numerous institutions are recognized in the migration strategies themselves, which point out the need to strengthen the state’s human, financial, and information resources.50 For example, Kosovo for a long time did not have a lead institution on migration, and until recently the diaspora unit in the competent ministry in Bosnia and Herzegovina had only six employees for over 2 million diaspora citizens.51 The institutions also do not have a synchronized and coordinated approach toward diaspora engagement. The policy documents are interlinked with previous institutional legacies, with the resulting lack of cooperation and harmonization as the main impediments to their implementation.

Monitoring and assessment of the implementation and impact of diaspora policies are likewise absent. Although formally the institutions have mechanisms in place, there are no available impact-assessment reports and analyses. The new laws and strategies do not evaluate the results of previous ones or note their progress; there is thus no evidence base or institutional consistency in implementation of the policies. Another reason is that some of the policies are still nascent so their efficiency and influence are yet to be seen. Civil society tries to compensate for these issues. One example is the Brain Drain Prevention Network in North Macedonia, whose analysis of the Brain Drain Strategy 2013–2020 showed an implementation rate of only 11 percent.52

- 1Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung, FES Youth Studies Southeast Europe 2018/2019.

- 2Albania was the exception. Under the rule of Enver Hoxha (1941–1985), it was a closed state with very strict migration policies. See Nermin Oruč, Emigration from the Western Balkans, German Federal Agency for Civic Education, 2022.

- 3Alida Vracic, The Way Back: Brain Drain and Prosperity in the Western Balkans, European Council on Foreign Relations, 2018.

- 4Tim Judah, Bye Bye Balkans, ERSTE Stiftung, 2021.

- 5According to one source, Kosovo lost 15.4 percent of its population between 2007 and 2018, the greatest decline in all of Europe, while according to other calculations it has lost only 4.27 percent since 1991. Mark Rice-Oxley and Jennifer Rankin, “Europe's south and east worry more about emigration than immigration – poll,” The Guardian, April 1, 2019; Tim Judah and Alida Vracic, The Western Balkans’ statistical black hole, May2, 2019, European Council on Foreign Relations. The United Nations data includes Kosovo’s population in that of Serbia, and the country possesses no reliable figures prior to the 2011 census. See Francesca Rolandi and Christian Elia, 2019: Escape from the Balkans, OBC Transeuropa, 2019.

- 6Cristian Gherasim, “Demographic crisis in the Balkans” EU Observer, January 10, 2022.

- 7See Isilda Mara and Hermine Vidovic, “The effects of emigration on the WB countries,” in Valeska Esch et al. (eds.), Emigration from the Western Balkans, Aspen Institute Germany, 2021.

- 8See reports by the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank, the Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies (WWIW), and other institutions.

- 9World Economic Forum, Global Competitiveness Report, 2019.

- 10Sandra M. Leitner, Net Migration and Skills Composition in the Western Balkans between 2010 and 2019: Results from a Cohort Approach Analysis, Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies, 2021.

- 11Ibid.

- 12Regional Cooperation Council, Study on Youth Employment in the Western Balkans, 2021.

- 13World Bank, Western Balkans Regular Economic Report, 2021.

- 14See, for example, Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung, FES Youth Studies Southeast Europe 2018/2019; Brain Drain Prevention Network in North Macedonia, Analysis of the Brain Drain Strategy 2013-2020; Westminster Foundation for Democracy, Cost of youth emigration in the Western Balkans, 2020.; and USAID, Cross Sectoral Youth Assessment North Macedonia, 2019.

- 15Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung, FES Youth Studies Southeast Europe 2018/2019.

- 16Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, International Migration Outlook 2019.

- 17A first (new) residence permit represents an authorization issued by the competent national authority in the EU allowing a national of a non-EU country to stay for at least three months on its territory for the first time. Eurostat, First Permits by Reason, Length of Validity and Citizenship, 2020.

- 18Ibid.

- 19International Organization for Migration, World Migration Report, 2018.

- 20Mara, The effects of emigration on the WB countries.

- 21Nermin Oruč, “Diaspora and regional relations” in Valeska Esch et al. (eds.), Emigration from the Western Balkans, Aspen Institute Germany, 2021.

- 22Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung, FES Youth Studies Southeast Europe 2018/2019.

- 23Miran Lavrič, Closer to the EU, Farther from Leaving, Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung 2019.

- 24Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung, FES Youth Studies Southeast Europe 2018/2019.

- 25Gallup, Potential Net Migration Index, 2017.

- 26Westminster Foundation for Democracy, Cost of youth emigration in the Western Balkans.

- 27Mara and Vidovic, “The effects of emigration on the WB countries.”

- 28George A. Akerlof, The Missing Motivation in Macroeconomics, American Economic Review, 97:1, March 2007.

- 29World Bank Group and The Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies, Western Balkans Labor Market Trends 2020, April 2020.

- 30UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, Probablistic Populations Projections Based on the World Population Prospects 2019, 2020.

- 31Norbert Mappes-Niediek, “My Europe: Eastern brain drain threatens all of EU”, Deutsche Welle, 2018.

- 32Dimitri A. Sotiropoulos, The Quality Of Democracy & Populism in Western Balkans, SciencesPo, October 6, 2016.

- 33Ana Krasteva et al, Maximising the development impact of labour migration in the Western Balkans Report, European Union IPA Programme for Balkans Region, 2018.

- 34The “Six Rs” responses consist of reparation, return, restriction, recruitment, resource, and retention policies, mostly used in developing countries. See B. Lindsay Lowell and Allan Findlay, Migration Of Highly Skilled Persons From Developing Countries: Impact And Policy Responses, International Labor Organization”, 2002.

- 35Mojca Vah Jevšnik and Sanja Cukut Krilić, Implementing the Posting of Workers Directive in the Western Balkans: An Institutional Analysis, European Centre for Social Welfare Policy and Research, 2019.

- 36A dual education system is one in which apprenticeships at a company are combined with courses in a vocational school.

- 37The EU’s Youth Guarantee aims to secure a smooth transition from school to work, support labor-market integration, and make sure that no young person is left out. The scheme should ensure that all young people under the age of 25 receive a quality offer of employment, continued education, or an apprenticeship or traineeship within four months of losing a job or leaving formal education.

- 38World Bank Group and The Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies, Western Balkans Labor Market Trends 2020.

- 39Regional Cooperation Council, Study on Youth Employment in the Western Balkans, 2021.

- 40For instance, youth in the EU enjoy incomes three times higher than youth in the WB6, while only 22 percent of WB6 youth had permanent jobs compared with 52 percent of their peers from southeastern EU members. World Bank, Western Balkans Regular Economic Report, 2020.

- 41World Bank Group and The Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies, Western Balkans Labor Market Trends 2020.

- 42Vlora Rechica and Natasha Ivanova, Youth unemployment in North Macedonia: an analysis of NEET and vulnerable youth, YouthBank Hub for Western Balkan and Turkey, 2020.

- 43Regional Cooperation Council, Study on Youth Employment in the Western Balkans, 2021.

- 44Krasteva et al, Maximising the development impact of labour migration in the Western Balkans.

- 45Jelena Predojević-Despić, “Migration and the Western Balkan Countries: Measures to Foster Circular Migration and Re-Migration” in Valeska Esch et al. (eds.), Emigration from the Western Balkans, Aspen Institute Germany, 2021. Also, interviews with representatives of civil society from the WB6.

- 46Ibid.

- 47Montenegro does not have clear brain-gain policies since it pursues a policy of open labor market and has been reforming its legal framework so as to comply with the EU Acquis Communautaire and simplify the process of engaging foreign workers. Through the Law on Foreigners, Montenegro applies a quota-based system in managing the influx of foreign workers.

- 48Nermin Oruč, Migration in the Western Balkans. What do we know?, Routledge, 2019.

- 49Ana Krasteva et al, Maximising the development impact of labour migration in the Western Balkans.

- 50Interviews with representatives of civil society from the WB6. See also National Strategy on Migration Governance of Albania; National Strategy of Diaspora of Albania 2018–2024.; Policy on Cooperation with Diaspora of Bosnia and Herzegovina 2017; Brain Drain Strategy of North Macedonia 2013-2020; Resolution on Migration of North Macedonia 2015; Resolution on Migration of North Macedonia 2017; Strategy for diaspora оf Republic of Serbia 2020; Economic Migration Strategy of Republic of Serbia 2021–2027; Law on Diaspora of Kosovo 2011; Strategy for Diaspora of Kosovo 2014–2017; Strategy for Integrated Migration Management of Montenegro 2017; and Law on Cooperation with Diaspora of Montenegro 2018.

- 51Krasteva et al, Maximising the development impact of labour migration in the Western Balkans.

- 52Brain Drain Prevention Network in North Macedonia, Analysis of the Brain Drain Strategy 2013-2020.

Brain Drain Prevention Network in North Macedonia, whose analysis of the Brain Drain Strategy 2013–2020 showed an implementation rate of only 11 percent.

Due to these institutional and policy flaws, there has been a limited impact in one crucial area of return and circulation policies: diaspora investments. Despite being among the top remittances countries in the world with over $9 billion received annually (between 5 and 8 percent of their respective GDPs), the WB6 have underutilized the investment potential of their diasporas. The size of remittances relative to investments varies from 2.9 percent in Serbia to 3.6 percent in Bosnia and Herzegovina and 4–8 percent in Kosovo.53 Administrative barriers, government inefficiency, and corruption are among the main impediments to small-scale diaspora investments.54 No specific data is available on young diaspora investors and entrepreneurs, yet, the negligible number of their returns, circulation, and engagement is a clear sign of the failure of these policies.

Data scarcity on migration is one of the biggest obstacles hindering the formulation of quality and informed return and circulation policies. The WB6 lack reliable, accessible, and systematic data in terms of the volume, characteristics, age, or skills composition of emigrants, which is a precondition for a comprehensive policy process. This is a shared challenge with even the most developed EU destination countries, which have different methods of data collection and incomplete mirror data, which further obscures the magnitude of brain drain from the WB6.55

In this context, population censuses are the primary source of migration statistics, with the most recent ones conducted over a decade ago (except for North Macedonia in 2021).56 The WB6 national statistical offices have a minor role in the production of data on brain drain and diasporas since they operate with outdated statistics and only register official emigration, which is inconsistent with the data from international organizations. For illustration, between 2005 and 2017, the State Statistical Office of North Macedonia registered only 12,558 citizens who emigrated.57 More importantly, the WB6 do not have nationwide and state-sponsored qualitative research on youth and brain drain. Such research is of high importance since it offers a “beyond the numbers” understanding of youth needs and trends. As noted above, the WB6 governments refer to the data and analysis produced by international organizations, donors, and civil society in formulating their migration policies.

Besides being providers of data and analysis, international organizations, donors, and civil society organizations are important actors and partners in policy design and implementation. Since the early 2000s, they have encouraged proactive approaches by the WB6 governments and spread good practices and know-how exchange across the region. In collaboration with national institutions, they have supported numerous programs and projects in policymaking, cooperation, and capacity-building; circular migration, return, and reintegration; and improving migrations data systems. These include the International Organization for Migration’s Migration for Development in the WB6 (2010–2012) and WB-MIDEX program, the German Agency for International Cooperation Migration for Development (DIMAK) program,58 the WB-MIGNET network, the United Nations Development Programme’s Brain Gain Program in Albania (2006–2011).59 However, despite their innovativeness and temporary success, these programs did not achieve substantial change. Again, the reason can be found in insufficient cooperation and coordination within institutions and the lack of result assessments. The institutions did not accept their leadership or endorse the potential of these programs, and eventually discontinued them due to lack of funding and interest.60

Last but not least, efforts to address youth brain drain are limited to the national level. The WB6 treat the issue exclusively as part of their national labor-migration policies. For a long time, the donor-led regional programs operated as modest examples of regional cooperation, outside of any formalized and institutionalized state-sponsored framework. Only with the establishment of the Regional Cooperation Council (RCC) in 2008, the Western Balkans Fund (WBF) in 2015, and the Regional Youth Cooperation Office (RYCO) in 2016 did the WB6 pave the way for more structured cooperation under EU auspices. The issue of youth brain drain is strongly present in the political agenda and public narrative of these regional organizations, affirming the political will to address this problem from a regional perspective. In 2020, it was labeled the biggest challenge of the new decade for the WB6 and the EU.61

Despite the political declarations, however, a clear vision regarding youth brain drain is missing among the WB6. There is no formal strategy or cooperation framework treating it as a question of the highest importance for the region. From a programmatic point of view, the regional actors work toward mitigation of youth brain drain indirectly (through employment, mobility, or cooperation) as a crosscutting problem. As a result, they do not have harmonized and coordinated actions. One of the reasons for this approach is the perception of bringing another difficult topic to the regional table beside the many that are already present.62

The most important and promising regional development has been the creation of the Regional Economic Area (REA) in 2017, which is managed by the Regional Cooperation Council. The REA’s purpose is to strengthen the region economically and to increase its competitiveness before its countries join the EU by copying its four freedoms and single market. The REA focuses on two crucial areas for tackling youth brain drain and encouraging circular migration: the regional investment agenda and the mobility of professionals, researchers, academics, and students (with regional mutual recognition of professional qualifications and diplomas).63 However, the spillover effects of bilateral issues and internal political turmoil in the region,64 alongside the six countries’ competition for FDI, further limit their interests to put the REA to full use.65 The lack of capacity of national institutions, of proper monitoring, and of elite buy-in are additional obstacles to the proper functioning of the REA.66

Shifting the Paradigm

A key precondition for mitigating youth brain drain is changing the public narrative at its core. Youth emigration is labeled as a negative phenomenon and inherently having adverse effects, which hinders the possibilities for a healthy debate. The first step toward changing this narrative is full recognition of the problem by the highest political actors in the region. Youth brain drain should be given the same weight as the WB6’s other difficult topics—such as reconciliation, trade, identity, and cooperation—and placed in the same political framework under the EU-led processes. In this way, youth brain drain can develop its role as the forerunner of WB6 development and be turned from an emotional issue into a policy and administrative one, while the WB6 administrations would be empowered to create and implement visionary and consistent policies resilient to political occurrences.

Although youth brain drain is one of the most worrisome problems for the WB6, it should not be presented only as such. It must be also seen as an opportunity that can be grasped with innovative solutions. Policymakers should present the other side of the story and create a positive narrative that would alter the notion of brain drain as a national defeat. This would entail advertising the full potential of return and circular migration as a new migration doctrine in the region. The existence of a vast resourceful diaspora of around 5 million people and their close relations with their home countries is a strong reason for such an approach.

More attention can be given to successful diaspora stories, diaspora data, diaspora-engagement approaches, comparative practices, or innovative policies.

International organizations, civil society, and the media will have a crucial role to play in opening up the space for introducing the potential offered by migration in the WB6 public discourse. Considering that these actors carry out public scrutiny and advocacy, they should better comprehend and present the multidimensionality of youth brain drain. They should abandon the orthodox approach of producing negative images, emotional stories, and shocking data that can be damaging to the policy process. This does not mean diminishing their role as watchdogs but refocusing their work to include communicating and showcasing the benefits of return and circular migration. More attention can be given to successful diaspora stories, diaspora data, diaspora-engagement approaches, comparative practices, or innovative policies.

In this context, the WB6 should pay particular attention to the example of Ireland. The country managed to utilize emigration to “reimagine and re-establish” its international credibility.67 Like the WB6 today, Ireland in the early 1990s had a high brain drain and an extensive diaspora. For it as well, brain drain was a difficult and emotional topic, and tackling this required strong and visionary political leadership, hard work, and compromises. Through a rebranding fully focused on tapping the diaspora’s potential for economic development—which was strongly supported by the media, business community, and civil society—Ireland managed to “turn water into wine” through a historical shift to return and circular migration policies and establishing itself as one of the most prosperous and attractive countries to live in.68

The impetus for an Irish scenario in the WB6 is there. Youth brain drain is a shared problem, following similar dynamics and dealt with similar policy approaches in all six countries. To date, the fight against it at the national level has had limited impact, making the individual efforts of the WB6 to retain or regain their young talents a losing battle. Regional policy solutions are the most viable option that will align all efforts of the six states, and reinforce the role of the EU and restore its shaken credibility in the region. This requires a prompt redesign of the policies used so far, based on the experiences and lessons learned to capture the current momentum. Using the leverage of the EU accession processes, the WB6 should initiate a new brain drain paradigm consisting of regional diaspora engagement, a new WB6-EU migration deal, and enhanced regional cooperation, all aimed to boost the return and circular migration of youth talent.

Paradoxically, the coronavirus pandemic has offered an opportunity to capitalize on the WB6 diaspora engagement. Recent history shows that emigration countries experience a high influx of diaspora circulation and returns in the aftermath of a huge economic crisis. This was seen in Bulgaria, Croatia, Poland, and Romania as a result of the economic crisis in 2008.69 In this regard, the WB6 governments need to rethink their approach to the nexus between diaspora and development and risk the socioeconomic peace that remittances bring with a new “beyond remittances” concept. This is especially appropriate now since remittances are rapidly losing their socioeconomic rationale due to the drop in their scale and their arguable impact on development.70

This is especially appropriate now since remittances are rapidly losing their socioeconomic rationale due to the drop in their scale and their arguable impact on development.

The “beyond remittances” concept would entail utilizing the full potential of the WB6’s educated and skilled youth diaspora by facilitating their direct investments and transfers of knowledge, skills, and networks. Mapping and research of this group should be the main priority. A regular and updated database will help to identify the skills, knowledge, and expertise of the diaspora youth talent that can be used for the socioeconomic betterment of the region. The WB6 should establish regular communication through diaspora contact points or already existing diaspora centers. Kosovo’s International Organization for Migration-supported You Are Part of the Homeland program, which has registered 400,000 diaspora members, is a positive example to follow.

Noting the limited capacities of the WB6 administrations, the role of the EU and its member states is paramount. For the benefit of both sides, the exchange of information and open data systems with the most popular EU destination countries such as Austria, Germany, Italy, or Slovenia should be established, while Eurostat as the leading EU body should work on building stronger relations and capacities of the WB6 state statistical institutions. Accordingly, the WB6 need to fully harmonize their legislation and policies with EU Regulation 862/2007 on migration, which will ensure the exchange of migration data. It is crucial that good practices such as the WB-MIDEX program and WB-MIGNET network be technically and financially supported in the future by the EU and WB6.

The leap from mapping to engaging youth diaspora will be an arduous task. The example of Ireland, as the more recent one of Estonia, shows this. Ireland dealt with this issue by stipulating financial guarantees and matching funds for investments, while Estonia—nicknamed “Europe’s little technological giant”—relied on information and communications technologies (ICT), digitalization, and e-business governance. Innovations such as e-residency and digital nomads’ visas welcomed a huge portion of Estonians home as well as attracting thousands of transnational entrepreneurs to the country.71 A similar example on a smaller scale comes from Bulgaria’s second-largest city, Plovdiv. In 2017, it had a positive immigration rate of 7 percent of 20 to 29 year-olds, bucking the national emigration trend, as a result of the blooming of its ICT sector, outsourcing companies, and digital nomads.72

As these examples show, encouraging diaspora members to invest or transfer their business back home cannot be based on patriotic sentiments. It is necessary to create a picture of the WB6 as a fertile ground for investments. This requires a good business climate and incentives that will have reasonable business logic to attract investments and transnational entrepreneurs. Returning Point in Serbia, Diaspora Invest Project in Bosnia and Herzegovina, and NGO Macedonia 2025 are just some successful initiatives that facilitate diaspora investments, connect homelands and diasporas, and create diaspora networks of knowledge and capital. To support this approach, the WB6 governments must invest significant funds to put in motion their diaspora and economic strategies. Building up the capacities of their administrations to revive already existing instruments such as Diaspora Development Funds, Diaspora Business Chambers, and Diaspora Banks will provide legal and financial certainty to diaspora (and other) investors.

- 53Danica Santic and Nermin Oruč, Highly-Skilled Return Migrants to the Western Balkans: Should we count (on) them?, Prague Process, 2019.

- 54Macedonia 2025 and Institute for Strategy and Development, Influence of the Macedonian Diaspora on the Economy, 2018.

- 55Silvana Mojsovska, “Possibilities for Regional Cooperation in Counteracting Emigration from the Western Balkans”, Valeska Esch et al. (eds.), Emigration from the Western Balkans, Aspen Institute Germany, 2021.

- 56The 2021 census in North Macedonia showed that in 20 years the country has lost 36 percent of its youth.

- 57National Strategy for Cooperation with the Diaspora in North Macedonia 2019-2023.

- 58Predojević-Despić, “Migration and the Western Balkan Countries.”

- 59UNDP, Research Study into Brain Gain: Reversing Brain Drain with the Albanian Scientific Diaspora, 2018.

- 60Predojević-Despić, “Migration and the Western Balkan Countries.” Also, interviews with representatives of civil society from the WB6.

- 61Regional Cooperation Council, “Bregu: Brain drain the biggest challenge of this decade - Western Balkans working age population declined by more than 400,000 in past 5 years,”January 28, 2020.

- 62Interviews with the Regional Youth Cooperation Office, Regional Cooperation Council, and the Western Balkans Fund.

- 63European Commission, Western Balkans Regional Economic Area, 2018.

- 64Regional Cooperation Council, Regional Economic Area Factsheet 2021. For instance, the REA has achieved modest progress since 2016, with trade increasing by 25 percent and FDI by 35 percent.

- 65Interviews with the Regional Youth Cooperation Office, Regional Cooperation Council, and the Western Balkans Fund.

- 66Richard Grieveson, Western Balkan economic integration with the EU: Time for more ambition, Balkans in Europe Policy Advisory Group, 2021.

- 67Mary Robinson, Cherishing the Irish Diaspora: An Address, February 1995.

- 68Alida Vracic, Luck like the Irish: How emigration can be good for the Western Balkans, European Council on Foreign Relations, 2019.

- 69Oruč, “Diaspora and Regional Relations.”

- 70World Bank Group, Leveraging Economic Migration for Development: A Briefing for the World Bank Board, 2019.

- 71Claudia Patricolo, Estonia: Europe’s Little Technological Giant, Emerging Europe, 2017.

- 72Maria Georgieva, “Reversing the brain drain: how Plovdiv lures young Bulgarians home”, The Guardian, 2019.

These investments are important since the diasporas usually bring entrepreneurial spirit, innovation, and affection to contribute to the development of their homeland. For instance, in Kosovo, returnees are more likely to start a business, while 98 percent of patents in Albania, 75 percent in Bosnia and Herzegovina, and 71 percent in Serbia are filed by returnees.

For this, the WB6 governments should replicate their approach to attracting FDI. Often criticized, but fairly successful, this approach sees them compete to attract investments through means including fiscal benefits and aggressive global promotion.73 Similar ambition and treatment should be shown for the diaspora investments as well. They need to have the same or more privileged fiscal treatment as FDI, as in North Macedonia’s Law on Financial Investments and receive legal and administrative support from the countries’ administrations. These investments are important since the diasporas usually bring entrepreneurial spirit, innovation, and affection to contribute to the development of their homeland. For instance, in Kosovo, returnees are more likely to start a business, while 98 percent of patents in Albania, 75 percent in Bosnia and Herzegovina, and 71 percent in Serbia are filed by returnees.74

The promotion of the WB6 as a destination for diaspora investments needs to be highly present in traditional and social media and to showcase the success stories of young transnational entrepreneurs and returnees as inspiration and encouragement for others. For example, stories such as the North Macedonian start-up Slice, founded by diaspora returnees that employ thousands of people globally, or of the Serbian start-up Nordeus add to the circular migration of young ICT engineers, entrepreneurs, data professionals, and marketers. There are numerous similar examples out there that need to be publicly recognized and celebrated.

Moreover, using the benefits of technology and modernization, the WB6 can unleash their diasporas’ human-capital potential through the remote transfer of knowledge, skills, and networks. Nowadays, it is a lot easier to facilitate this transfer via ICT, requiring less effort to convince the skilled diaspora to circulate or return. Programs for virtual returns and virtual circulation, especially in academia, research and development, and the business sector need to be established. Additionally, “think nets,” virtual research networks, and virtual consortiums are alternatives that can be further explored. The BH Futures Foundation from Bosnia and Herzegovina is an excellent example that digitally connects the entrepreneurial diaspora with the country’s youth and creates virtual spaces for exchange and networking.

The success of circulation and return policies does not depend solely on the WB6. Modern migration is managed and dictated by the destination countries. As the EU and its member states such as Austria, Germany, Italy, and Slovenia are further liberalizing their labor markets, their leverage and accountability for the brain drain problem grow. However, the EU has completely put the ball in the WB6’s court by helping them through its accession mechanisms to improve their competitiveness. There are numerous sound and legitimate reasons for this, yet EU migration policies lack a recognition of the pull factors, the socioeconomic benefits to destination countries, and the negative effects of brain drain, making the EU a “dishonest broker”75 when it comes to the region’s demographics.

No country would give up on the benefits that skilled and educated youth migrants bring. Nevertheless, EU-WB6 relations are peculiar as a result of the EU accession issue and of geographical proximity, which have created strong dependency. The EU depends on the WB6’s skilled labor and the WB6 on diaspora remittances, investments, and knowledge. For the EU, there is also the fact that it needs a progressive and democratic region as a strategic partner but this is hard to achieve given the massive brain drain that diminishes these countries’ prospects of EU membership. And, as seen from the examples of Bulgaria and Romania, aside from all other benefits, EU membership decreases the negative effects of youth brain drain.76

From this standpoint, brain drain and EU accession are mutually exclusive for the WB6.

From this standpoint, brain drain and EU accession are mutually exclusive for the WB6. The EU has the interest and instruments to favor domestic reforms in WB6, but simultaneously it needs to take responsibility for their youth brain drain. Without joint management of the problem, both sides risk a “lose-lose” situation in the long run. As Germany’s Minister for Foreign Affairs Heiko Maas noted in 2020, “We [in the EU] cannot close our eyes to the problems that a continuous brain drain is causing in the WB.”77 By not acting promptly and more fairly, the EU further weakens its position and credibility in the eyes of the WB6’s citizens.

A new WB6-EU migration deal could be a worthy alternative to consider. A milestone step for this deal should be the 2020 Economic and Investment Plan for the WB (WB Plan) and the 2021 WB Agenda on Innovation, Research, Education, Culture, Youth and Sport (WB Agenda) in which brain drain is tackled more openly and concretely through the EU’s economic, social, and innovation policies. The conditionality of the enlargement process should include brain drain as a crosscutting issue, creating an environment for circular migration as the most realistic and preferred by “knowledge migrants” today.78

Furthermore, the WB Agenda reaffirmed a regional rather than individual approach to the WB6 as an “essential policy for enhancing human capital development, stopping brain drain and encouraging brain circulation through evidence-based policy and transition to a knowledge-based economy.”79 To fully capitalize on these new EU policies, the WB6 need to strengthen and professionalize their administrations, businesses, and university sectors to better exploit the EU’s Instruments for Pre-accession Assistance and programs such as Erasmus+ and Horizon Europe, and to accelerate academic and professional exchange between the two sides.

For its part, the EU should enrich the WB Agenda’s actions with strong and attractive return and circulation mobility schemes and partnerships. EU FDI and outsourcing companies as well as the bilateral agreements between WB6 countries and member states have already created firm institutional and business partnerships on which this policy shift can be built. This will motivate young students, professionals, scholars, and entrepreneurs to “learn and earn” in the EU and then transfer their capital, knowledge, and skills to their home countries. Job mobility and co-employment for young ICT professionals, engineers, doctors, and scholars in the EU or temporary capacity-building and professional development programs with returning clauses are options. A good example is the Microsoft Development Centre in Belgrade, which traditionally employs returnee engineers and ICT talent from across the WB6. There is a large potential for such measures in the healthcare field as well, bearing in mind the number of doctors of WB6 origins residing in the EU.

The biggest resource in the fight against brain drain is enhanced regional cooperation supported by the soft-connectivity EU-WB6 policies.

Considering the above, the biggest resource in the fight against brain drain is enhanced regional cooperation supported by the soft-connectivity EU-WB6 policies. The WB Plan and other key EU policies identify regional cooperation through the Common Regional Market (CRM) as an advanced Regional Economic Area as a key pathway for economic and investment connections that should bring the region closer to the EU.

The factors in favor of the regional approach are manifold. The difference between economic and the human-capital potential of the region and its small individual economies is notable. An integrated WB6 market of 18 million people has the potential for additional growth of GDP of 6.7 percent.80 And regional cooperation is strongly supported by the WB6 citizens. The Balkan Barometer 2021 found that 77 percent of them support regional cooperation and count on it to improve the political and economic situation in their countries.81

- 73From 2016 to 2020, FDI amounted on average to between 5 and 7 percent of GDP of the WB6. Chamber Investment Forum: Western Balkans 6.

- 74Vracic, The Way Back.

- 75Alison Carragher, The EU is a dishonest broker on the Western Balkans demographics, Carnegie Europe, 2021.

- 76Miran Lavrič, “Youth Emigration from the Western Balkans: Factors, Motivations, and Trends”, in Valeska Esch et al. (eds.), Emigration from the Western Balkans, Aspen Institute Germany, 2021.

- 77Hamdi Firat Buyuk, “Balkan Brain Drain ‘Won’t Stop Without Economic, Democratic Progress” Balkan Insight, 2020.

- 78EU Commission, Economic and Investment Plan for the Western Balkans, 2020.

- 79EU Commission, Western Balkans agenda on innovation, research, education, culture, youth & sport, 2021.

- 80EU Commission, Economic and Investment Plan for the Western Balkans, 2020.

- 81Regional Cooperation Council, Balkan Barometer 2021 - Public Opinion.

Due to their linguistic, cultural, and geographical proximity, the WB6 should focus on the systematic support of regional mobility. Currently, intra-regional emigration accounts for approximately 23 percent of the WB6 total migration.

Furthermore, with the stalling of the WB6 accession processes and the mixed signals about eventual EU membership, the CRM should be the major political and policy priority of all WB6 governments. The WB Plan should be used to rethink the region and create conditions for the return and circular migration of its youth talent. Due to their linguistic, cultural, and geographical proximity, the WB6 should focus on the systematic support of regional mobility. Currently, intra-regional emigration accounts for approximately 23 percent of the WB6 total migration, with around 60–65 percent of intra-regional immigrants being aged 24–49.82 Hence, reaching a prompt consensus on the legal basis for an agreement on the recognition of professional and academic qualifications as the main precondition for free mobility and cooperation of young professionals, scholars, students, and researchers is of utmost importance. The WB Plan offers the innovative idea of establishing a Regional Diaspora Knowledge Transfer Initiative to utilize the regional diaspora potential and promote brain circulation. In this way, the WB6 collectively can become more attractive and competitive, not to only convince more young citizens to circulate and return, but also to attract foreign youth talent.

To make proper use of such opportunities, the WB6 should learn from previous mistakes within the REA. The capacities and influence of the Regional Cooperation Council as an implementing body should be strengthened to make youth and youth brain drain a central topic on the political agenda. A joint stance with the EU in the form of a declaration, strategy, or resolution would give the desired leverage to turn this into concrete policies. This is needed since, in contrast with the WB6 Plan, the CRM Action Plan 2021–2024 omits to properly acknowledge youth brain drain. On the other hand, the RYCO has not received recognition as the leading regional organization and reference point for youth in the CRM. Currently, the RYCO is not part of the political and policy dialogue built up around the WB Action Plan.

To overcome this lack of synchronization among the key regional organizations, the Regional Cooperation Council and the RYCO need a common vision and approach under the CRM. As part of this, there must be independent mechanisms and resources for implementing youth and brain drain policies. The creation of a common committee or commission on brain drain, composed of national and international experts could help to align their programs, integrate national interests, and increase their advocacy effectiveness.

Alongside the free movement of people, the free movement of capital is equally important to promote regional circulation and return.

Alongside the free movement of people, the free movement of capital is equally important to promote regional circulation and return. The investment space opened by the WB Plan is a key opportunity for the six governments to address one of the main shortcomings—funding. The WB Plan amounts to €9 billion, supports FDI, and secures it with the new WB Guarantee Facility. With proper promotion and outreach, these funds and mechanisms can be used to attract the desired diaspora investments. Similarly, the WB6 can promote diaspora investment policies within the region, bearing in mind that the WB6 diaspora replicates the ethnic divisions from their homelands, which can produce more feasible opportunities for regional investment projects by the diaspora community from the region.83

In terms of investments, the coronavirus pandemic can open a window of opportunity for the WB6. The EU’s future investment plans follow a “near-shoring” policy; that is, one of transferring supply value-chains closer to the EU. Instead of competing with one another to benefit from this, the WB6 must position themselves collectively as an investment region. Open and profound regional investment cooperation with a clear vision will alleviate the economic push factors for brain drain and would mean more circulation and return of youth talent, transnational entrepreneurs, scholars, and professionals. This is an opportunity for the region as a whole to rebrand itself through the creation of key regional value chains, in which each country can contribute to the production of goods and services in line with its capacities and previously agreed investment plans. The automotive, ICT and tourism industries can be good starting points.84

Conclusion

The chance for the WB6 to keep or attract their youth home is here, which may be the last one. A new brain drain paradigm focused on the potential of the WB6 youth diaspora and based on enhanced regional cooperation and enriched relations with the EU is a crucial option to consider. In light of the aftermath of the coronavirus pandemic and of the new EU-WB6 soft-connectivity approach, youth brain drain should be part of the conditionality framework for EU accession, gaining equal status as the other difficult questions in the region. As a shared problem, youth brain drain requires shared solutions, visionary actions, and hard regional compromises. Whether the WB6 will keep and attract their young and talented people home is one of the factors that their EU aspirations and their democratic and economic progress depend on.

As a complex problem, youth brain drain needs full recognition as a separate policy area, at the national and regional levels. In the process, it should be analyzed not only as a negative phenomenon that is often misused by the political parties, but also as a viable opportunity for socioeconomic development, bearing in mind the financial assets, know-how, and networks of the youth diaspora. This narrative change can be achieved by following the Irish model of open collaboration among the WB6 governments and all other relevant stakeholders such as international donors, the media, civil society organizations, and youth themselves.

The WB6 should be presented as a fertile ground for diaspora investments that offer legal certainty and professionalism of institutions, something that all six countries need to seriously work on. This can be achieved by mimicking the approach to attracting FDI, deepening the CRM, and promoting the success of diaspora entrepreneurial stories. Innovative and tech-savvy young talent should be mapped, reached out to, and offered collaboration through virtual tools and networks that can ease the facilitation of knowledge and experience sharing. A new migration deal with the EU as a more accountable partner can support the mobility and exchange of WB6 youth talent as a strategic action in the long run. Among other elements, the WB Plan and WB Agenda offer an excellent starting point for further strengthening the capacities of, and cooperation between, the key regional actors to carry out these political and policy innovations in the spirit of the CRM.

Appendix

Expand AllAbout the Author

Marjan Icoski is a program manager at the organization for social innovation ARNO in North Macedonia. He has rich experience in civil society and academia, specializing in international programs, research, and funding for youth and human rights education. His main expertise includes youth migration and youth employment, social entrepreneurship, regional cooperation, and EU integration with a specific focus on the Western Balkans. Marjan also worked as an academic tutor at the ERMA MA program in human rights and democracy at the University of Bologna where he currently acts as an alumni relations manager and visiting lecturer. He holds an LL.M from the Ss. Cyril and Methodius University in Skopje, and an MA in human rights and democracy from the University of Bologna.