Transatlantic Explainer: EU–U.S. Privacy Shield

The annual review of the EU–U.S. Privacy Shield — the key mechanism for the transfer of personal data between the United States and Europe — begins today. The review will assess implementation of the Privacy Shield framework and U.S. privacy protections and associated laws. It will also be a major test of the health of the transatlantic relationship under President Donald Trump.

Why is data privacy a big deal in the transatlantic relationship?

Differences over privacy and the protection of personal data have long been irritants in the transatlantic relationship. While the European Union takes what it describes as a “rights-based” approach to privacy and other cyber-norms, it has characterized the U.S. approach as “commerce-based,” privileging economic considerations above the protection of citizens' rights. The protection of personal data is so central in the European Union that it is enshrined in the eighth article of the EU’s Charter of Fundamental Rights, which became binding after the passage of the Lisbon Treaty in 2009.

Under the EU's 1995 Data Protection Directive, personal data can only be transferred outside the EU if the Commission has determined that the receiving country provides “adequate” protection for such data, the individual provides “informed” consent to the transfer, or contractual constraints on the use of the data exist in the form of model contract clauses or Binding Corporate Rules. The 2016 update of the Directive, the new General Data Protection Regulation, retains this approach to international transfers of personal information.

While only five countries outside Europe have been deemed “adequate” by the Commission, transfers of data to the United States were permitted under the 2001 U.S.–EU “Safe Harbor” agreement, under which companies agreed to constraints on how they used European citizen data. The June 2013 revelations of former National Security Agency contractor Edward Snowden indicating that the U.S. government had accessed a wide range of personal information held by U.S. companies, however, dealt a mortal blow to Safe Harbor, made official when the European Court of Justice (ECJ) in October 2015 agreed with Austrian law student Max Schrems' complaint that Facebook was not adequately protecting his data in United States. While the Data Protection Directive does not cover national security or law enforcement considerations, the ECJ ruled Safe Harbor invalid, as the European Commission had not considered whether the United States had sufficient “democratic controls” over government access to personal data held by Safe Harbor companies.

What is privacy shield?

In 2016, the European Commission and the U.S. government agreed to the Privacy Shield to replace Safe Harbor as a mechanism to permit the transfer of EU citizen data to the United States.

Among other things, the agreement:

(1) sets out obligations for companies with respect to how they process and handle the personal data of EU citizens;

(2) provides written assurances that U.S. government access to data for national security and law enforcement purposes will be subject to safeguards, limitations, and oversight; and

(3) creates an “ombudsperson” within the U.S. Department of State to respond to European concerns regarding national security access to data.

In the aftermath of the ECJ decision, the Obama administration adopted a series of measures limiting surveillance of non-U.S. citizens. Privacy Shield is effectively contingent upon the continuation of those measures. Particularly important is Presidential Policy Directive 28, a 2014 executive order that places significant limitations on U.S. surveillance of non-U.S. citizens. PPD 28 and the other measures together allowed the Commission to find that companies participating in Privacy Shield provide essentially equivalent protections for European data.

Why does Privacy Shield matter?

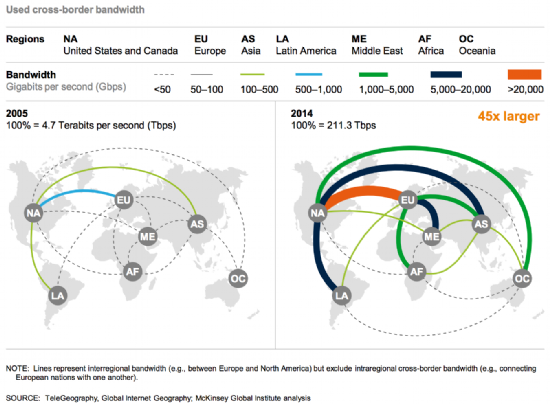

It is difficult to overstate the importance of cross-border data transfers to the transatlantic economic relationship. The movement of data across borders is fundamental to business in every sector of the economy, not only for technology firms but also for manufacturers, service providers, and IP-intensive companies, whether large or small.

Cross-border data flows between the United States and Europe are the largest in the world, 50 percent higher than data flows between the United States and Asia, and almost double the data flows between the United States and Latin America. It is almost inconceivable that the European Union would prohibit the flow of personal data to the United States, even though the ECJ judgment says data transfers to third countries that cannot guarantee the EU level of protection should, in fact, be “prohibited.”

If cross-border data flows were to be seriously disrupted — which would be the case in the absence of a reliable data transfer mechanism such as the Privacy Shield — the economic harm to both Europe and the United States would be immediate, widespread, and profound. Among countless other daily business impacts: insurance companies may not be able to write new policies in European or U.S. markets without access to policyholder data; European coders collaborating with others outside of the EU may no longer be able to write open-source software, where the code is hosted on U.S. servers; and EU-based manufacturers may not be able to move employee or customer data in order to manage production, delivery, and distribution.

To the extent that there is continued policy and legal uncertainty regarding whether companies may move data from Europe to the United States, companies, workers, and consumers on both sides of the Atlantic suffer. While the protection of personal data is doubtless a critically important policy objective, so too is ensuring that data can move freely to spur innovation and enable companies to create jobs and grow their economies. The Privacy Shield represents an effective policy recipe for advancing both innovation and data privacy simultaneously, but policymakers must be prepared for developments that could require them to alter the ingredients of that recipe in the future.

What are the current political and legal dynamics surrounding the Privacy Shield?

While the Privacy Shield establishes that the United States meets European “adequacy” requirements for the time being, many government officials, legislators, data protection authorities, and civil society groups in Europe (and some in the United States) believe that the U.S. legal system still does not effectively protect EU citizen data. Both the Privacy Shield and other methods for transferring data are being challenged in European courts; a single negative court judgment could dismantle the Privacy Shield and plunge transatlantic data transfers into uncertainty.

This week's ministerial-level annual review will be an important opportunity to evaluate how both companies and the U.S. government have modified their policies and practices and, by extension, whether the Privacy Shield appropriately protects EU citizen data under EU law. While most observers expect that the two sides will find the Privacy Shield to be operating effectively, there is substantial ongoing litigation within European courts challenging both the Privacy Shield itself and other aspects of the EU's approach to cross-border data transfers. Officials on both sides of the Atlantic will need to prepare for the implications of either a policy or legal determination (or both) within Europe that the Privacy Shield is simply not up to snuff.

(A more detailed timeline is available by clicking here.)

The European Commission's endorsement of the Privacy Shield was challenged by many in the European Parliament and by a series of data privacy watchdogs. The challenges described above indicate its continued fragility. In the statement announcing its implementation, the Commission put the importance of the transatlantic relationship front and center, saying:

“We have common values, pursue shared political and economic objectives, and cooperate closely in the fight against common threats to our security. The enduring strength of our relationship is evidenced by the extent of our commercial exchanges and our close cooperation in global affairs.”

Given the enduring importance of both cross-border data flows and the protection of personal data, it is clear that the survival of the Privacy Shield will depend on the strength of the transatlantic relationship writ large.