Closing Window: Transatlantic Cooperation on China Under Biden

Summary Points

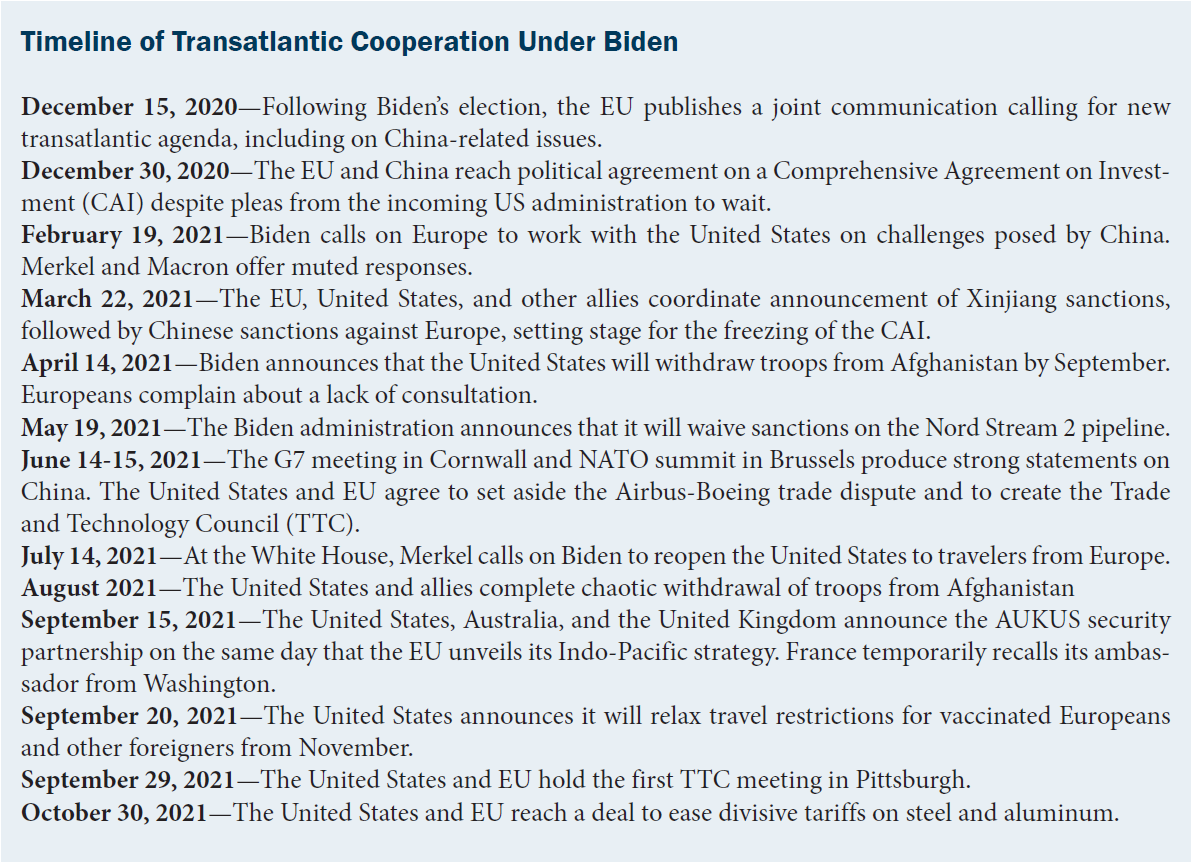

In its first year, the Biden administration has focused on repairing damage to the transatlantic relationship under Trump and setting up structures for greater allied cooperation on China. Progress at the G7, NATO, and EU summits has been followed by the setbacks of Afghanistan and AUKUS.

The window of opportunity for transatlantic cooperation on China could close fast, with the U.S. midterm and French presidential elections posing risks. It is crucial for Europe and the United States to deliver big wins in 2022 to restore faith in cooperation.

The United States must clarify its aims with regard to China while Europe, under the leadership of a new German government, must forge a greater consensus on China policy. Both sides must accept that their alignment will be imperfect and not let that get in way of their broader goals.

An insular turn by China, particularly in run-up to the Communist Party congress in late 2022, could drive the United States and EU closer, but Beijing will continue to look for ways to exploit transatlantic tensions.

Last February, one month into his presidency, Joe Biden took to the podium in the White House and made an impassioned plea to European leaders to work with his administration on what he described as one of the “most consequential” challenges of the 21st century. “We must prepare together for a long-term strategic competition with China,” he told an event hosted by the Munich Security Conference.1 The responses from Germany’s Chancellor Angela Merkel and France’s President Emmanuel Macron, who were also participating, were muted at best. Merkel acknowledged the need for a transatlantic discussion on China, but tempered expectations, saying “our interests will not always converge.” Macron ignored Biden’s plea on China completely and offered a vigorous defense of strategic autonomy, arguing that Europe needed to take care of its own defense and to move beyond its dependence on the United States. It was an early signal to Biden and his new administration that Europe, despite its own concerns about China’s political and economic development under President Xi Jinping, would not be an easy partner when it came to their top foreign policy priority: responding to a rising China.

In the year since Biden was elected, this awkward transatlantic dynamic has continued to play out. Steps forward in forging a common agenda on China, such as the G7, NATO and EU-U.S. summits in June, have been followed by setbacks, including the chaotic withdrawal from Afghanistan and the Biden administration’s nuclear submarine deal with Australia and the United Kingdom, which infuriated France. The Biden administration has gone out of its way to try to repair the transatlantic damage of the Trump years, taking steps to resolve long-standing trade disputes, including over steel and aluminum and between Airbus and Boeing, halting sanctions tied to the Nord Stream 2 pipeline, and reversing Trump administration plans to reduce U.S. troop levels in Germany.

But in accelerating the United States’ pivot to Asia, the Biden administration has also reinforced the notion in European capitals that Washington will be a less reliable partner in the future. Today there are still questions in Europe about the administration’s endgame with China, how far it plans to push the idea of economic decoupling, and whether there is any hope of avoiding a full-blown confrontation between the United States and China. Within the Biden team, there is frustration with what is seen as a lack of European urgency in relation to China, German fence-sitting, and French attempts to distance Europe from the United States. “The United States wants to confront China. The European Union wants to engage China,” France’s Finance Minister Bruno Le Maire said in October.2 Europe remains deeply divided on China, with countries like Lithuania pushing a more hawkish line and others like Hungary continuing to cozy up to Beijing. These divisions have made it difficult for Europe to have a coherent conversation on China with the United States and other allies.

A Rapidly Closing Window of Opportunity

Despite all of the above, there is no alternative to closer cooperation on China if the United States and Europe want to defend democratic values, human rights, and the rule of law around the world, to establish widely accepted standards for the digital era, and to ensure their economic and national security. The looming change of government in Germany, which will usher Angela Merkel off the political stage after 16 years as chancellor, could lead to a shift in Germany’s approach to China and alter the broader European dynamic—even if major policy changes are unlikely. The first meeting of the EU-U.S. Trade and Technology Council (TTC) in Pittsburgh in September has injected momentum into the transatlantic discussion on essential issues like investment screening, export controls, supply-chain resilience, data governance, and technology standards. But the window of opportunity for closer cooperation is closing fast. A setback for Biden in the midterm elections next year, would increase doubts about whether the Democrats can hold onto the White House in 2024, emboldening those in Europe who reject the notion of close alignment with Washington and support a policy of geopolitical hedging in relation to China. A defeat for Macron in France’s presidential election in April could increase the risks of a “France first” foreign policy approach in the EU’s second-biggest member state, potentially deepening divisions in Europe and making transatlantic cooperation on the full array of geopolitical challenges even more difficult.

Priorities for 2022

In this kind of environment, it will first be important for Europe and the United States to deliver some big wins in the months ahead that restore faith in the potential for transatlantic cooperation. The first year of the Biden administration has been largely about repairing the damage of the Trump years and bedding down structures for allied cooperation—from the Quad with Australia, India, and Japan and the TTC to a planned Summit for Democracy in December. The coming year will need to be about delivering concrete results that will be difficult for future administrations to reverse.

To achieve this, the Biden administration will need to be clearer about its aims in relation to China—particularly in the economic sphere. If it is not prepared to lay out a positive global trade agenda due to domestic political constraints, at the very least it needs to explain better where it wants to put the balance between national security and economic engagement with China.

Europe will need to work on its divisions and develop a long-term vision for relations with China that a wide group of countries can buy into. Since unveiling the EU-China Strategic Outlook in March 2019—the policy document that described China as a partner, competitor and systemic rival—the European Commission has advanced a comprehensive defensive agenda to respond to China. But the EU has struggled to build a broader political consensus among its member states.3

Europe and the United States must also be cognizant of and push back against attempts by China to exploit transatlantic strains. While a softening of Beijing’s aggressive diplomacy seems unlikely in the run-up to an important conference of the Chinese Communist Party in late 2022, where Xi will be seeking a third term, China has, in the past, shown a knack for making timely tactical concessions—for example, in its talks last year with Europe on a Comprehensive Agreement on Investment (CAI)—to drive a wedge between the transatlantic partners.

Delivering Big Wins

It will be essential for the United States and the EU to build on the broad agenda laid out at the TTC meeting in September to deliver real results in the months ahead. This will require compromises and a willingness to expend political capital on both sides of the Atlantic. There are quick wins to be had in areas where there is already a strong basis for consensus, such as the fight against disinformation, the push for closer cooperation within multilateral organizations, and on human rights. The coordinated announcement of Xinjiang sanctions in March 2021 sent a powerful signal, as did the pledge by European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen, in her state of the union speech in September, to introduce import bans in the EU for products made from forced labor. A deal to ease divisive Trump-era tariffs on steel and aluminum, announced at the G20 meeting in Rome, also has the potential to generate some transatlantic momentum.

More important, however, will be bold collective action in areas where there is no transatlantic consensus at present. It will be important to think big and to tackle thorny issues around data governance and new technology standards. In the economic realm, developing a coordinated transatlantic approach on semiconductors that averts a self-defeating race to the bottom on subsidies would be an important breakthrough, as would identifying joint high-profile infrastructure projects in third countries as part of a transatlantic response to China’s Belt and Road Initiative. Germany’s G7 presidency in 2022 provides an opportunity to bring some coherence to the proliferation of new connectivity initiatives, from the G7’s Build Back Better World plan to the EU’s new Global Gateway project.

In the security realm, Taiwan is a delicate but critically important area for transatlantic dialogue and coordinated messaging. The debate is evolving in Europe, as reflected in a new report on Taiwan relations from the European Parliament4 and recent remarks from the European Commission Executive Vice President Margrethe Vestager, who described recent displays of force by China in Taiwan’s air defense identification zone as a direct threat to European security and prosperity. With Lithuania currently a victim of economic retaliation by China because of its support for Taiwan, it will be important for EU member states to begin a broader discussion about their approach as a prelude to talks with the United States. The EU-U.S. dialogue on China, launched in May, could put this issue front and center.

Clarifying U.S. Aims

The Biden administration has left in place much of the Trump toolbox on China, from tariffs and entity listings to investment bans. Its rhetoric on China, however, has been different: U.S. officials now repeat on an almost daily basis that they are not out to contain or confront China, and that they do not want another Cold War. Lately, there have been signs that they are ditching the histrionic “great power competition” framing of the Trump administration in favor of a more sober “strategic competition” approach that will be easier for U.S. allies to embrace. But U.S. officials are still confronted with a recurring question when they visit European capitals: what is Washington’s endgame with China?

In the security realm, the AUKUS security pact between the United States, Australia and Britain has sent a strong signal about the U.S. commitment to counter China’s growing influence in the Indo-Pacific. But the administration has sent mixed signals about how it views Europe’s role in the region, encouraging a greater European presence while at the same time appearing to play down its importance. Does the administration see U.S. and European interests in the Indo-Pacific as compatible? And how can Europe’s new ambitions in the Indo-Pacific be reconciled with those of the Quad? These are questions that must be tackled head-on rather than brushed under the carpet.

In the economic realm as well, the Biden administration will have to do a better job of articulating its aims over the coming year. How does it see the United States’ economic relationship with China evolving? Does the administration reject the concept of decoupling, as Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo suggested recently?5 Are terms like resilience and diversification more appropriate when describing an economic relationship that will be impossible to untangle completely? There are clearly divisions within the Biden administration on these questions. Resolving them and charting a clearer course for U.S. policy is necessary to deliver a leap forward in transatlantic coordination on China. China is a complex challenge that is not easily reduced to buzzwords. But where Trump offered simplistic clarity, the Biden administration has often sent ambiguous signals. Biden’s first year has been a missed opportunity in terms of reframing the decoupling narrative in a way that encourages buy-in by U.S. allies. It will be important to deliver a clearer message in his second year.

Tackling European Divisions

A change of government in Germany following the recent parliamentary elections opens a window of opportunity for Europe to address its divisions over China policy and to try to forge common principles for engagement with Beijing. The three parties currently engaged in negotiations to form a coalition government—the Social Democrats, the Greens, and the Free Democrats—have all stressed the importance of a collective European response to China. Achieving this in a bloc of 27 member states will not be easy. And it has been made more difficult by the AUKUS deal, which has added fuel to France’s push to put more distance between Europe and the United States. But a more joined-up EU approach is possible if Germany is willing to put European interests above its own narrow economic priorities. The clearer Europe is about its own priorities, the simpler the transatlantic discussion on China will be.

What would this look like? First, Germany will need to prioritize an in-depth EU-wide discussion on China policy. This has not taken place in a substantive way since the EU unveiled its Strategic Outlook paper in 2019. This discussion could culminate in a mid-2022 summit of EU leaders, during France’s presidency of the European Council, that aims to give new impetus to a common European approach. By then, a new German government will be in place and the dust will have settled on France’s presidential election. Second, as part of this process, the EU should intensify a push to end the decade-old 16+1 format with China that includes numerous member states in Central, Eastern and Southern Europe. The format is already teetering, following the departure of Lithuania and the refusal of numerous EU states to send leaders to the last summit with China in February. More withdrawals could put the nail in its coffin, but this is unlikely without assurances from EU institutions and big member states that any retaliation by China against individual countries will be met with a collective European response. Ending 16+1 would not be a game changer, but it would send a powerful signal about European unity.

The China Wild Card

The wild card in all this is China’s own behavior. Its image has suffered in Europe, in the United States, and across much of the democratic world over the past two years as a result of its crackdown on democracy in Hong Kong, its human rights violations in Xinjiang, its saber rattling with Taiwan, and its aggressive “wolf warrior” diplomacy and coercive economic policies since the outbreak of the coronavirus pandemic in early 2020. Over the past year, China has launched a push for greater self-reliance in critical economic sectors, pressuring foreign firms to localize their supply chains as part of its “dual circulation” strategy. Together with Beijing’s recent crackdown on domestic technology firms, this push is raising new questions about the future for foreign businesses in China. At the same time, the sanctioning of European lawmakers and research institutions in March 2021, in response to the EU’s narrowly targeted Xinjiang sanctions, has left the EU’s push for a more reciprocal economic relationship with China in tatters. As 2021 draws to a close, there is no obvious pathway for reviving the CAI. The EU is also poised to roll out new defensive tools—from an instrument for dealing with foreign subsidies and legislation on supply-chain due diligence to new anti-coercion tools—that could deepen political and economic tensions with Beijing.

If the past two years are a sign of things to come, China’s policies are likely to push Europe and the United States closer together. Despite repeated promises that it will continue to open up, it is hard to imagine China veering away from the nationalistic, insular course of recent years so long as Xi is in power. As he moves towards securing a third term, Beijing may even double down on this course.

Nevertheless, over the coming year, it is also likely that China will seek ways to drive a wedge between Europe and the United States, whether by offering European companies favorable treatment or making bold climate promises that reinforce the sense in European capitals that dialogue with Beijing can deliver results. The success of transatlantic cooperation on China will depend in part on how adept leaders in Europe and the United States are in resisting attempts to divide them through a combination of inducements and threats.

Imperfect Alignment

Ultimately, the United States and Europe will need to accept that perfect alignment on China will not be possible—and to ensure that their differences do not get in the way of broader goals. The aim should be a gradual convergence of views across the Atlantic on how the challenges presented by China’s rise are understood and tackled. As U.S. National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan said during a visit to Europe in October, “We view this as a process, we view it as an arrow in a direction that is trending towards more convergence between the U.S. and Europe.”6 But both sides will need to move out of their comfort zones to ensure that this convergence takes hold. Biden’s election one year ago opened the door to a more structured transatlantic discussion on China. But with a closing window of opportunity, both sides will need to step up their engagement, work toward greater coherence in their own strategies, and deliver concrete results in 2022 that help chip away at lingering problems of transatlantic trust.

- 1Joe Biden, “Remarks by President Biden at the 2021 Virtual Munich Security Conference,” The White House, February 19, 2021.

- 2Liz Alderman and Roger Cohen, “Clear Differences Remain Between France and U.S., French Minister Says,” The New York Times, October 11, 2021.

- 3European Commission, “EU-China – A Strategic Outlook,” March 12, 2019.

- 4European Parliament, “EU-Taiwan relations: MEPs push for stronger partnership,” October 21, 2021.

- 5Aime Williams, “US Commerce chief pushes China trade despite complicated relationship,” Financial Times, September 28, 2021.

- 6David Herszenhorn, “Biden’s top security adviser sees strong transatlantic alliance (and no jumping in lakes),” Politico, October 11, 2021.