France’s Presidential Elections in the Shadow of Ukraine

As a result, candidates who had built their campaigns on domestic concerns are struggling to create momentum and President Emmanuel Macron’s position as Commander in Chief has set him above all other contenders. The next resident of the Elysée will have a decisive impact on France’s response to the crisis in Ukraine and, more broadly, on European security and transatlantic cooperation. Here is what France’s allies and partners can expect from the different candidates.*

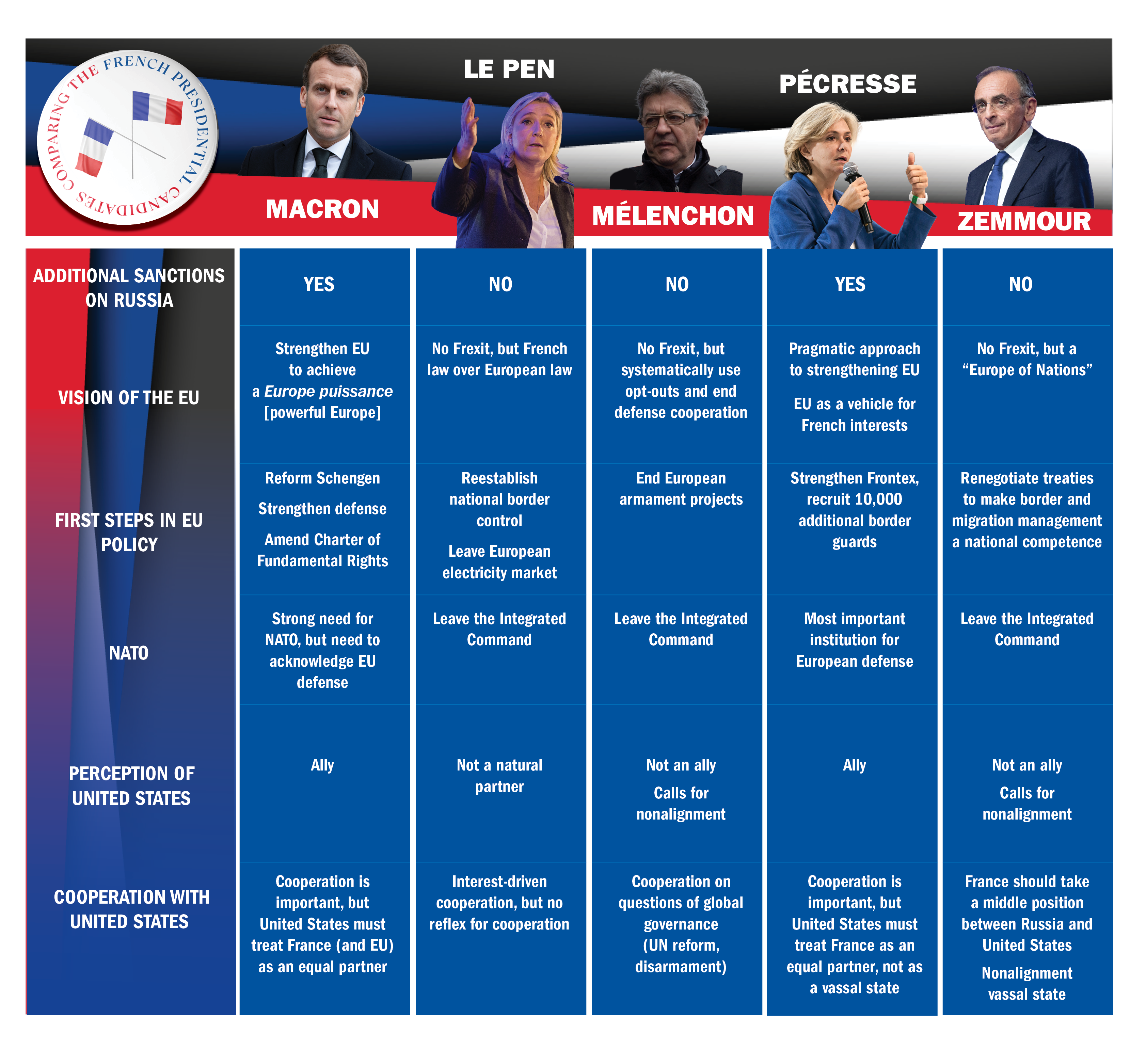

Emmanuel Macron (En Marche, centrist-liberal): European Sovereignty with Transatlantic Cooperation

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine completely changed President Macron’s plan for the first half of 2022. Leveraging the rotating French presidency of the Council of the European Union while running a presidential campaign at home was seen as Macron’s main challenge, but the war in Ukraine has nearly put his campaign on ice, particularly because he is Europe’s last communication channel with Russia. The president’s popularity has recently skyrocketed—with nearly 30 percent of voting intentions in recent polls, he is by far the front runner.

Macron put Europe at the heart of his 2017 campaign, and the idea of European strategic autonomy, later renamed European sovereignty, has been the golden thread linking his policies together. Concretely, this has included pushing for more investments in key sectors including electronic chips, space, and defense, and better regulation of strategic industries like online platforms and digital giants. Macron is convinced that only a strong European Union will allow France to make itself heard in the world, but beyond this pragmatic view of the union, he is also a staunch believer in a distinct European identity. Accordingly, he vows to strengthen the power of Europe through enhancing energy autonomy, extensive investments in European tech champions, and strengthening capabilities and cooperation of European armies. Another Macron presidency likely means a continuation of his current line on Europe and proposals made during the French presidency of the EU Council, such as the reform of the Schengen system or the amendment of the Charter of Fundamental Rights.

Against the backdrop of Macron calling NATO “brain-dead” in 2018—referencing the alliance’s deadlock due to diverging strategic interests—it may appear paradoxical to label him the most transatlantic of all candidates. Yet, Macron has been systematic in claiming that a stronger EU, including through defense, is perfectly compatible with NATO. Since the beginning of the crisis in Ukraine, Macron has continuously underlined the need for a strong NATO in Europe, and Washington would most likely find a reliable ally in Paris if it were willing to see Europe as an equal partner. Following their meeting in Rome in late 2021, Macron got Biden’s formal commitment to support a stronger European defense strategy. Their meeting gave a glimpse of what to expect from Macron in terms of transatlantic cooperation, with potential new initiatives on tech, outer space—an issue prioritized by French policymakers but sparking little interest among other Europeans—and climate change.

- *The first round of presidential elections in France will be held on April 10 and the second round on April 24. This article only covers the candidates with at least 10 percent of the intentional vote in public opinion surveys. In total, 12 candidates are running in the first round.

What to expect from a second Macron term?

All in for European sovereignty, more European defense initiatives, focus on EU technological sovereignty, cooperation with NATO on strengthening EU defense, reform of Schengen, reaffirmation of France’s role in the Indo-Pacific as a “power of the balance.”

Marine Le Pen (Rassemblement National, far right): Stay in the EU, but without EU Rules

Marine Le Pen, in her third and perhaps last presidential run, represents a euroskeptical and sovereigntist French foreign policy based on a strong narrative of national identity. Le Pen is convinced that France is decaying and must find a way back to its former grandeur [greatness]. To her, playing an active role as a global power can only be achieved through an unapologetic, independent approach to foreign relations. Accordingly, her foreign policy prioritizes unilateralism over multilateral cooperation within institutions and she supports cooperation “among independent states.”

A Le Pen presidency would be bad news for Europe. Though she had lobbied for a Frexit over many years, her position changed with Brexit, and today she calls for a fundamental transformation of the EU toward a “Europe of Nations,” implying a transfer of supranational competences back to national capitals. Le Pen advocates for reinstalling the primacy of French legislation over EU legislation and hence abandoning the primacy of EU law—she considers the EU an “illegitimate supranational structure.” Most importantly, Le Pen is opposed to any European defense effort and wants to reestablish national border controls but simplify the process for EU citizens. Having criticized “German domination” in Europe for years, Le Pen would likely limit French-German interstate cooperation, though it would probably continue through the countless existing civil society initiatives. At the institutional level, Le Pen would undoubtedly prioritize France’s interests to the detriment of any joint initiative.

Transatlantic relations would also suffer during a Le Pen presidency: she is convinced that French defense should be exclusively French and has vowed to take the country out of NATO’s integrated command structure. To her, the United States is both an ally and a rival, which explains her critical posture vis-à-vis Washington. But the war in Ukraine forced her to backtrack after having pushed for closer cooperation with Moscow, even though her campaign material still features an image of her shaking Putin’s hand as an example of her efforts to build relationships with “leaders of patriot movements.” Her entourage maintains that dialogue with Russia on challenges of global governance remains crucial, and regarding its war on Ukraine, she insists on prioritizing a diplomatic solution and argues that economic sanctions might harm purchasing power in France. Le Pen does not see the United States as a natural partner for France and emphasizes that she aims to build sovereign relations with it on selected issues, and under the condition that these do not harm France’s relations with other countries.

What to expect from a Le Pen presidency?

No meaningful cooperation with Europeans or the United States, strengthened French instead of European capabilities in areas such as defense and tech, French blockage of key transatlantic initiatives on Russia, institutional paralysis of European foreign and security policy due to French veto, defense of freedom of navigation in the Indo-Pacific but co-investment with China in certain domains.

Jean-Luc Mélenchon (France Insoumise, far left): Leave NATO and Transform the EU (or Leave It)

This year’s presidential elections mark Jean-Luc Mélenchon’s third attempt at the presidency. He placed fourth in 2017 with 19.6 percent of the vote, relatively close to Marine Le Pen’s 21.3 percent, and currently ranks third according to surveys on the intentional vote, with around 15 percent. His score has steadily increased over the past weeks, fueling his hopes of making it to the second round of the elections, even though Le Pen is more likely to do so.

Like Le Pen and Eric Zemmour, Mélenchon’s foreign policy proposals have been discredited by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Prior to the attack, Mélenchon defended Putin, stating that he understood Russia’s need to flex its muscles with a military buildup on the border with Ukraine and asking, “Who wouldn’t do the same with a neighbor country that is linked to a menacing power?” alluding to the United States. He is a firm believer in French nonalignment and has pushed hard for operational independence, notably pointing to what he perceives as a lack of help in Mali from allies. In fact, to him, the abrupt end of the Barkhane mission is proof that “a Europe of defense cannot exist.” Furthermore, he calls for ending European armament projects like the French-German Future Combat Air System. Despite all this, he does not support a Frexit, believing it would create economic chaos for France, but he wants to use opt-outs systematically each time the treaties forbid one of his campaign promises.

He does, however, support leaving NATO’s integrated command since he sees NATO as an imperial tool that the United States uses to subdue its allies. He even went so far as to question France’s defense commitment to fellow EU member states, stating that he did not understand why France should intervene militarily to protect the Baltic states in case of a Russian invasion. Calling for a “diplomacy of nonalignment,” Mélenchon vows to give up France’s alignment with the United States but sees Washington as a negotiation partner particularly for multilateral challenges, such as a reform of the United Nations or disarmament.

What to expect from a Mélenchon presidency?

Against EU defense integration, against NATO, lack of interest in transatlantic relations and security cooperation, no alignment with US strategy in the Indo-Pacific but focus on nonalignment to protect French overseas territories.

Valérie Pécresse (Les Républicains, center right): More of the Same

When Valérie Pécresse won her party’s primaries, many projected her as Macron’s most serious challenger. By blending law and order and liberal economics, she seemed poised to reconquer the center-right vote, which traditionally supported members of Les Républicains but voted for Macron in 2017, following the scandal that rocked François Fillon’s campaign. However, she has struggled to distinguish herself from the president, whose liberal economic policies, defense strategy, and recent decision to limit visa deliveries to Algeria and Morocco by 50 percent and to Tunisia by 30 percent significantly resemble her own proposals; currently, most polls put Pécresse at between 10 and 11 percent of intentional votes. More recently, the war in Ukraine has pushed her campaign to the sidelines while boosting Macron’s standing.

Pécresse’s foreign policy proposals also closely resemble those of Macron. She has expressed support for a stronger European Union, particularly in defense; views Europe as a vehicle through which France can project its power; and desires more systematic military collaborations with European partners. Still, unlike Macron, whose program is based on a shared European identity, she has a more pragmatic vision of integration, aligning herself with her mentor, Jacques Chirac. She would also end Turkey’s integration process, veto any further enlargement, and push for more control over immigration flows, notably by recruiting 10,000 more Frontex border guards. In her own words: “we must reform the EU-27 before thinking of its enlargement.” To defend French interests in Brussels, Pécresse stresses the need to reestablish a more balanced Franco-German relationship but does not specify what that entails.

France’s independence on the international stage is of paramount importance to the traditional center right and Pécresse is no exception. To her, France must be “an ally of the United States, but certainly not a vassal state.” She sees AUKUS and the botched Franco-Australian submarine deal as proof that US priorities lie in the Pacific, and that it is willing to implement its geostrategic shift at the expense of its historical allies in Europe. Nevertheless, she is convinced that the defense of Europe must go first and foremost through NATO. Furthermore, she wants to give a new impetus to Franco-American cooperation to defend French interests, suggesting an annual visit to Washington for a constructive dialogue.

What to expect from a Pécresse presidency?

Centrist and pragmatic approach to the EU, focus on EU immigration policy, stronger European tech cooperation, pragmatic and interest-based approach to bilateral relations with the United States, against NATO expansion to the Indo-Pacific, and French alignment with US strategy.

Eric Zemmour (Reconquête, far right): France First—and Independent Foreign Policy

Eric Zemmour’s campaign announcement last November greatly upset the political balance of the presidential election. Until then, most analysts expected a repeat of 2017 with a face-off between Le Pen and Macron, but Zemmour’s surprise run divided the right, splitting Le Pen's electorate in half and greatly reducing her certainty of reaching the second round. However, while he had built momentum prior to his campaign’s official launch, notably by playing on public anticipation, he faced backlash from all sides for using over a hundred copyrighted elements in a campaign video. His standing in the polls has steadily declined since, putting him between third and fourth place.

Of all the candidates, Zemmour is the most euroskeptical. Though he does not support a Frexit, he is also opposed to any further integration. His vision of Europe is one based on realpolitik, in which the special nature of the Franco-German relationship is a mirage. In fact, he argues, Germany has systematically put its interests ahead of Europe’s and therefore France should do the same, particularly when it comes to defense. In practice, that means raising the national defense budget to 70 billion euros by 2030, increasing the size of France’s standing army by 20 percent, and building a new aircraft carrier, all while stepping up the export of arms to key allies in Europe and beyond.

But despite his strong focus on defense, the war in Ukraine has greatly reduced his chances of success. In the weeks leading up to the war, he repeatedly dismissed US intelligence reports of Russia’s belligerent intents and expressed his sympathy for Putin, calling him “an authoritarian democrat.” Even in the face of public outcry following the invasion, he held his ground. For him, “if Putin is guilty, the West is responsible.” These controversial statements are reflective of his “third way,” or his strategic nonalignment between Russia and the United States, whom he sees more as an adversary than an ally. Zemmour also believes France should strive for independence and leave NATO’s integrated command.

What to expect from a Zemmour presidency?

Unclear position on Russia, complicated cooperation with Europeans and the United States, withdrawal from defense integration through EU or NATO, renegotiation of security partnership with United States in the Indo-Pacific, focus on national tech and defense initiatives.