Made in the EU: Mechanisms for Burden-Shifting in European Security

Europe has got the message. The United States expects European countries to accelerate burden-shifting and take more responsibility for the continent’s security. NATO will almost certainly remain the central organization for collective defense and deterrence, but the EU can—and should—take on a greater role. Many of its tools are overlooked, but can in fact add value and make meaningful contributions to European security.

To fully tap the potential of the EU for empowering NATO, Europeans must overcome their own long-held doubts about the EU’s capacity as a security actor. Commitments to improving EU-NATO cooperation have been included regularly in joint statements of both institutions as well as in EU strategies, but the cooperation today is mostly technical and bureaucratic in nature. European leaders must take advantage of the EU’s capabilities and enhance EU-NATO cooperation to succeed in transatlantic burden-shifting. Efforts should focus on three areas: the defense industry, crisis management, and collective defense against low-level threats.

Leveraging the EU in these three areas will not be a silver bullet, as existing initiatives and mechanisms are relatively less powerful than NATO or national solutions. Nevertheless, these EU initiatives provide the direction of travel for European states. In the medium to long term, an increased role for the EU can support them in strengthening the European contribution to the defense of the continent.

Financial and Industrial Acceleration

In response to Russia’s war against Ukraine, EU member states and institutions have increasingly relied on the EU’s financial power and industrial policy to meet their capability needs.

They should now use the EU’s instruments more actively to fulfil the needs of European defense based on NATO’s capability plans. EU member states can use the mechanisms outlined in the 2025 White Paper for European Defence in a way that reinforces NATO needs. The most recent instrument to do so is the SAFE legislation, which unlocks €150 billion in loans to member states for common procurement. SAFE suffers, however, from two shortcomings: First, it only partially refers to NATO standards. Most member states will use the instrument to procure capabilities that contribute to NATO goals, but use of the tool could have been incentivized more heavily by making this a condition for joint procurements.

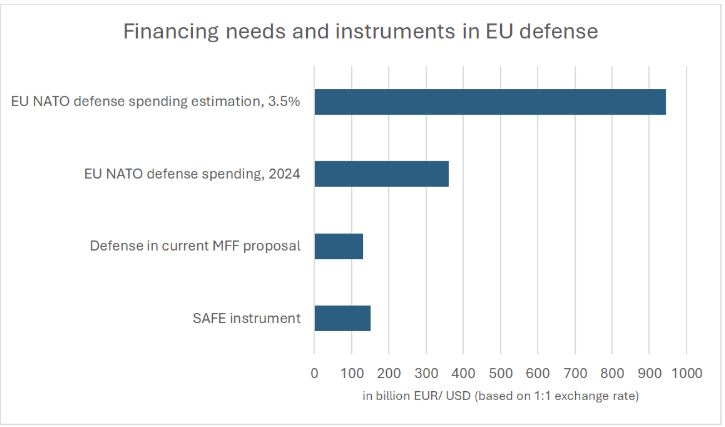

Second, the total financial envelope of SAFE remains relatively limited compared to Europe’s capability needs in the conventional domain. Estimates for the required investments range from €500 billion over the next decade to an increase by €250 billion annually in the case of a full US withdrawal. Within NATO, states have agreed to ramp up defense and defense-adjacent spending to 3.5% and 1.5% respectively: If they follow through, this would imply a total defense spending by EU NATO member states of $944 billion, an increase of around $580 billion. Accordingly, SAFE is a helpful starting point for member states to jointly procure materiel and contribute to the harmonization of military systems, but its financial scope is insufficient to meet national capability requirements.

SAFE alone cannot, therefore, ensure European rearmament. But these efforts are important because they effectively reduce the cost of “non-Europe” (national-level solutions) through efficiency gains, reduced fragmentation, and more effective use of resources. The current cost of non-Europe in European defense is estimated at €18 billion to €57 billion annually. Given the limited financial capacity of SAFE, member states should use the instrument strategically, for example prioritizing sophisticated smaller systems such as drones, C4ISR capabilities, or space capabilities. This approach would create a common base of future systems, align with NATO’s capability goals in these domains, and allow European states to advance the defense industrial base. The relatively lower cost of more limited capabilities could ensure broader participation of member states regardless of their fiscal situation. Even if SAFE might appear financially unattractive in the short term, fiscally strong member states that can borrow at more attractive rates should participate to achieve the long-term gain of harmonization of European systems. Fiscally weaker member states could benefit from advantageous borrowing rates through the EU. In both cases, the financial cost for the member states would be relatively low, with spillovers for future defense cooperation.

Beyond the White Paper and SAFE, the new Multiannual Financial Framework (MFF)—the EU budget for 2028–2034—offers opportunities to boost European capabilities. The current proposal allocates €131 billion to security and defense under the European Competitiveness Fund, a five-fold increase from the current MFF. EU member states should maintain or even increase this level of ambition, as the proposed amount represents only one-fourth of the expected necessary investments to ramp up their defense spending to 3.5%. The European Commission will also have a key role to play in ensuring that the funds are allocated in a way that boosts European capability through cooperation. Such measures could include joint research on cutting-edge technologies and additional financing access for joint projects by small and medium-sized enterprises.

Because of the gap between funding provided and financial needs, these financing instruments will not be game-changers. But leveraging them can help construct a European defense industrial base and “made in Europe” capabilities.

CSDP Missions: Crisis Management as an EU Task

The EU and NATO should jointly develop ways to gradually shift crisis management tasks into the EU framework. Although the EU’s Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP) missions still need to draw on NATO’s or national operational headquarters to operate, the political discussions could be held in the EU, potentially with the participation of third states. This approach has two advantages: It allows NATO to focus on its core tasks of deterrence and collective defense and helps European states make a good case for the United States to remain engaged in NATO. They can argue that this approach reduces the risk of US entanglement in regional conflicts that mainly affect Europe.

Transferring crisis management into the EU would clearly signal the willingness of Europeans to handle regional crises on their own. As these missions are mostly small in scale—in total, 3,500 military and 1,700 civilian personnel are currently deployed in the missions—the political symbolism will clearly be more important than the de facto alleviation of military burden on the United States. Europeans should therefore also frame this shift as part of a broader alliance reform

Maritime security can serve as a blueprint for burden-shifting on crisis management and operations outside Europe, as illustrated in the Indian Ocean, the Red Sea, and the Gulf of Aden. While NATO’s Mission Ocean Shield and the EU Mission Atalanta were launched at about the same time, the NATO mission ceded its operations in 2016—and today, EU member states conduct the anti-piracy mission independently.

Especially when European interests such as stability and security in its neighborhood are at stake, EU member states need to develop an “EU first” reflex on crisis management. This approach would also signal to Washington that Europeans do not aim to “transatlanticize” security challenges that primarily affect Europe.

This increasing division of areas of responsibility between NATO and the EU also implies that European states must give more political attention to crisis management—even if that seems to go against the zeitgeist and the focus on territorial defense and deterrence. The potential benefits for transatlantic relations and for the EU merit this attention. More flexible, faster, and better coordinated responses to crises on the EU side signal to Washington that Europe is making efforts on all fronts to reduce its dependence on the United States.

Collective Defense: Article 42.7 TEU

European states generally agree that NATO should oversee collective defense and deterrence. However, they should not shy away from using article 42.7 of the Treaty on European Union (TEU) for collective defense. As the EU’s mutual defense clause, article 42.7 TEU calls upon member states to provide “aid and assistance by all the means in their power” if a member state “is victim of armed aggression on its territory”. Discussions of this possibility have not been taken seriously to date, but should advance quickly, especially in light of the uncertain future of US engagement in European security.

Most importantly, European states need a common definition of cases where article 42.7 TEU—potentially instead of NATO’s article 5—should be used. The obligation to assist does not require EU-level consensus, but member states can determine the scope of their support. In contrast, NATO’s article 5 requires the North Atlantic Council to formally define the attack against the member state as an attack against all. The political threshold for NATO’s article 5 is thus significantly higher than that for the EU’s article 42.7 TEU. As part of burden-shifting and taking more responsibility for the continent’s security, European states could establish a staged model of threats and link them to mechanisms for collective defense. They could propose to Washington that they use article 42.7 TEU instead of invoking NATO’s article 5 for attacks where a response can be coordinated among Europeans only. Such cases could include terrorist attacks, hybrid attacks, or cyberattacks— as when Paris used article 42.7 TEU instead of turning to NATO after the terrorist attacks of 2015. At the same time, the United States—which invoked article 5 in reaction to the 9/11 terrorist attacks—should pursue a similar approach inside the alliance and continue to prioritize the defense against nuclear and conventional threats over hybrid, cyber, and terrorist threats in the NATO context.

A key challenge, however, is the limited military capacity of the EU. Three options appear likely in response to an activation of article 42.7 TEU. The lowest-hanging fruit is individual support by member states and multinational coordination. Alternatively, EU member states could opt to center decision-making in the European Council, provided they unanimously agree. This would allow them to use article 44 TEU to delegate the task to a group of member states that would in turn be led by a member state. Another EU option for action consists in drawing on the Military Planning and Conduct Capability (MPCC), which is expected to assume full command and control of the EU’s Rapid Deployment Capacity (RDC) in 2025.

EU member states could work towards a de facto division of labor between the EU and NATO on collective defense. The collective response to lower-threshold, non-existential threats could be coordinated by EU member states only, whereas NATO’s role would remain largely unchanged for collective territorial defense. In this context, a reaffirmed US commitment to NATO’s article 5 would also help maintain the alliance’s deterrent effect on Russia.

The three proposed actions are not game-changers for the challenges of European security and defense. Nevertheless, using EU mechanisms and instruments can accelerate burden-shifting and create a European defense space in which the Europeans, through the EU, structurally take on more responsibilities for challenges that they can—and should—manage themselves. European states and the United States should not undervalue this potential avenue, but actively use it.