Toward Defining and Deploying the European Interest(s)

Editor's note: To download a copy of this report, click here.

Summary

Adopting the traditional concept of the “national interest” to the European level through the definition of “European interests” will help improve EU policymaking overall and assist EU leaders in garnering public support for actions taken to those ends.

The EU’s status as a hybrid—part state, part international organization—without a monopoly on the legitimate use of force within its territory and from which member states can choose to leave requires that European interests are defined much more broadly than traditional national interests focused on states’ physical self-preservation. Instead, European interests must be defined as those indispensable for the continued preservation of the EU as a well-functioning entity with its fundamental institutions and democratic values intact.

Some European interests are revealed by the solutions adopted in their defense during acute EU crises. They can also be motivated by the EU’s desire to resist the effects of other countries’ extra-territorial policies outside the national security and military realm, the need to retain a size that helps retain its global influence as its share of global GDP and population declines, or the need to collaborate given the nature of the challenges the EU face. As the EU is unlikely to evolve into a single, wholly sovereign entity, it will continue to possess fewer traditional military and national security assets than its economic weight would otherwise suggest, and it must temper the scope of its related European interests accordingly.

Based on this approach, six distinct European interests are identified. Some are simultaneously of a domestic and an external nature for the EU, and their designation as being domestically or externally oriented is to indicate their predominant orientation. These interests will also overlap and may even occasionally come into conflict with each other. They are:

- Preserving basic democratic values and the rule of law in the EU.

- Maintaining broadly similar economic trajectories among EU member states and regions

- Securing the EU’s role as a global leader in the fight against climate change.

- Upholding a credibly and uniformly controlled EU external border.

- Maintaining constructive and principled relations with EU neighbors.

- Sustaining a cooperative international system and sustaining good relations with like-minded third countries.

Introduction

The EU has had since 2019 a “geopolitical Commission”1 —in the words of its president, Ursula von der Leyen—aiming to invest in alliances and coalitions to advance European values, and to be a champion of multilateralism. The EU Council as far back as 2016 defined the union’s “strategic autonomy” as the ability “to act autonomously when and where necessary and with partners wherever possible,”2 a modus operandi then echoed in the European External Action Service’s Global Strategy for the European Union’s Foreign and Security Policy.3 Even before the coronavirus pandemic, there was plenty of official focus on why and according to what guidelines the EU should act together in the world. Perhaps this has been due to the increasing number of state-like capabilities the EU has granted itself in recent years—a bailout fund, a border guard, and a (supposedly one-off) common counter cyclical fiscal policy just to name a few.

The global political and economic environment the EU must navigate meanwhile remains unpredictable and challenging. While the election of Joe Biden as president of the United States has meant that, at least at the executive level, “America is back,” it has not restored a bipartisan consensus on U.S. foreign and economic policy in Congress. And the new global power in China and regional powers bordering the EU such as Russia and Turkey continue to promote increasingly nationalist and authoritarian political agendas frequently at odds with the global rules-based system and institutions. Perhaps because of these persistently testing global circumstances, policymakers and experts often voice concerns and frustrations about the EU’s recurring inability to act quickly and collectively on the things that should matter most to it and its residents.

Distributed EU sovereignty and the union’s geographic and societal diversity are inevitable challenges to a consensus emerging in many European policy areas. Member states will often see the world through their national lenses and perceptions about threats and policy priorities.4 Aggravating this tendency of decisionmakers to remain focused on the narrow—though politically intuitive and domestically widely shared—notion of the “national interest” is the absence of a clear and coherent notion in EU capitals of the common interests they share.

Not articulating and utilizing the notion of collective European interests is a lost opportunity to promote EU common decisions.5 The lack of a constructive, positive, widely shared, and coherent definition of these further leaves the idea open to abuse in the public arena by self-interested political forces. In an EU in which the political space to act forcefully, quickly, and jointly often only exists at times of acute crises, a clearheaded ex ante understanding of what Europe’s common interests are is crucial.

This paper aims to contribute to the debate about why, when, and how the EU should act collectively by adapting the concept of the national interest at the pan-European level and offering a lucid definition of what the European interests are. The concept entails a degree of agency and ability to act in Europe’s name, which here only the EU is assumed to possess despite it not encompassing all European countries. Thus, the EU is the institutional actor that potentially wields the European interest.

These European interests will be assumed to be politically contestable and likely to change over time. Accordingly, while consensus on common EU actions will be facilitated by the consideration of genuine European interests in the policy-formation process, it will often be incumbent upon political leaders to persuade voters to support the prescribed common causes of action.

The first section of the paper adapts the concept of the national interest at the European level and demarcates it from other categories of interests and political incentives. The second section lays out the key drivers of common European interests today. The third section then presents a comprehensive list of current European interests. The final section considers how to utilize a “European interest benchmark” to continuously evaluate EU policies and proposals as well as to maximize the constructive contribution of the concept of the European interest to EU policy formation.

This paper has been inspired by ongoing discussions in 2021 among members of an expert group6 convened by the German Marshall Fund as well as by a European citizens’ consultation in the context of the European Interest(s) project. It will be presented in a number of European countries, as the project attempts to insert the concept of shared European interests into national political decision-making processes.

- 1Ursula von der Leyen, Speech in the European Parliament Plenary Session, European Commission, 2019.

- 2European Council, European Council meeting (15 December 2016) – Conclusions, 2016.

- 3European External Action Service, Shared Vision, Common Action: A Stronger Europe. A Global Strategy for the European Union’s Foreign and Security Policy, 2016.

- 4One aspect of the current development of the EU Strategic Compass is an attempt by member states to reach shared risk perceptions and a common understanding of the threats and challenges facing the EU.

- 5This is analogous to the manner in which the European External Action Service argues that the development of shared risk and threat perceptions in the EU Strategic Compass will promote common policies: “At the same time, the notion that the Strategic Compass contributes to develop the common European security and defense culture, informed by the EU’s shared values and objectives, should be well reflected.” European External Action Service, Scoping Paper: Preparation of the Strategic Compass, 2021, p. 2.

- 6The group consisted of David O’Sullivan, Stormy Annika Mildner, Ben Judah, Malgorzata Szuleka, Nad’a Kovalcikova, and George Papaconstantino, and met virtually five times during 2021.

The European Interest(s): What’s Needed to Keep Europe Together?

Join us in the Berlin on Thursday, November 11 to discuss this publication defining the European Interest(s) and addressing these pressing issues.

Adapting the National Interest Concept at the European Level

The concept of the national interest focuses on countries’ conduct of foreign policy.7 It is often criticized, however, for failing to provide a sensible metric for judging national-level political action. A “national interest” is defined as the interest of a nation as a whole, held to be independent and separate from the interests of subordinate areas (in the EU case, this would mean individual member states) or groups, as well as of other nations or supranational groups. The concept is elusive and subject to endless interpretations, spanning everything from isolationism to outward aggression, in effect making the national interest whatever policy governments want to pursue at any moment. In open pluralistic democracies a broadly shared consensus about what constitutes the national interest should generally not be expected. Yet, the notion retains some descriptive and even predictive value in policy formation pertaining to the one issue that most experts tend to agree is the most basic national interest, namely a country’s physical self-preservation. As Henry Morgenthau noted, “all countries do what they cannot help but do: protect their physical, political, and cultural identity against encroachments by other nations.”8

The postwar reliance by most EU member states on NATO and the U.S. security umbrella for physical security complicates applying such an elementary conception of national interest at the European level. The traditional division of labor with NATO arguably makes this largely a non-issue for the EU. Member states have persistently since the end of the Cold War spent limited amounts of resources on traditional defense-related matters: 1.2 percent of GDP on average in 2019.9 This highlights how most EU governments do not prioritize traditional physical security. With interstate peace the norm for decades and the EU facing challenges in many other policy dimensions, its policymakers might think themselves excused for feeling preoccupied elsewhere.

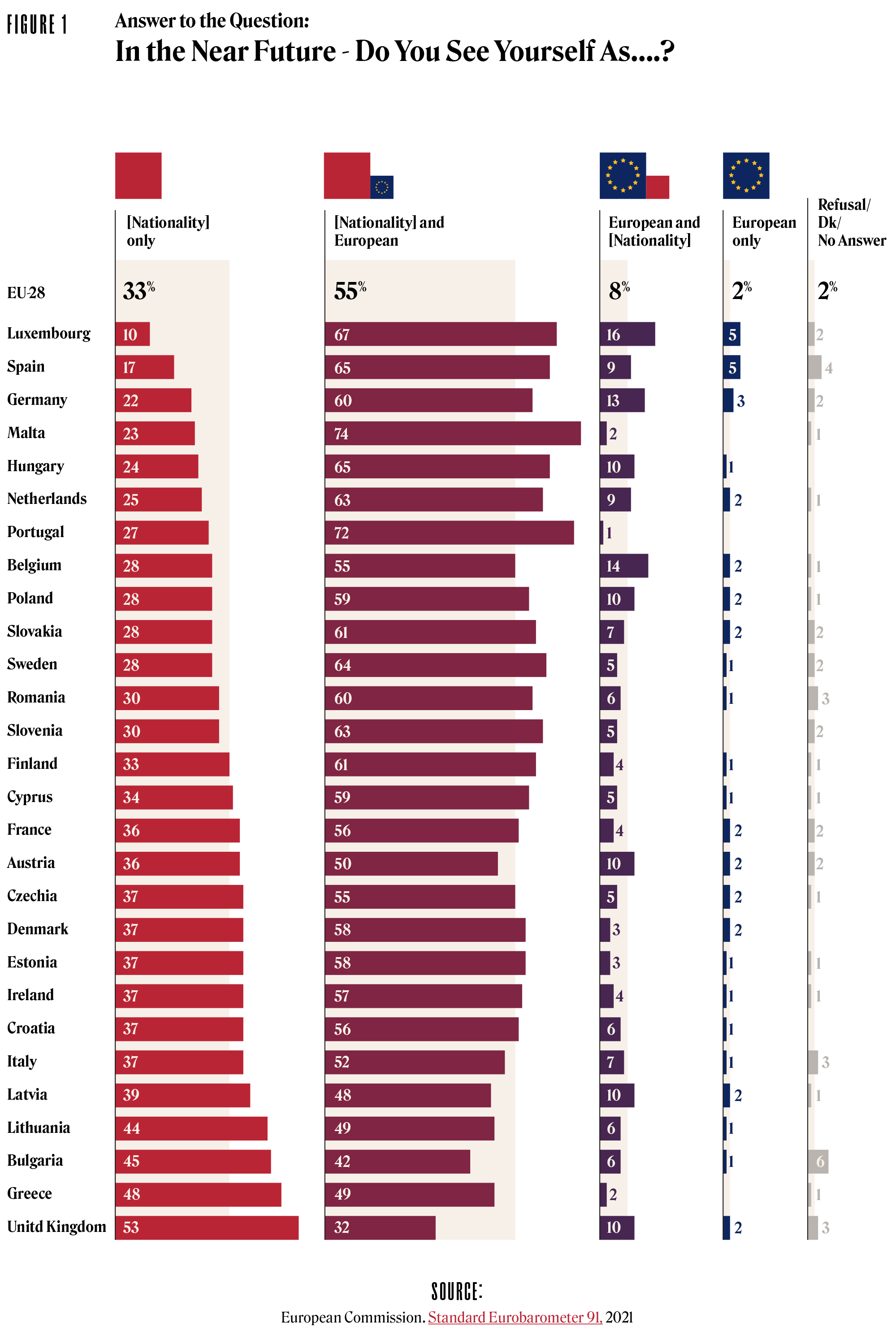

Moreover, as advocacy by political leaders is invariably required for the establishment of any consensus regarding national interests, and the complex ways Europeans self-identify put further hurdles in the way of the construction of widely supported European interests. EU residents overwhelmingly and persistently self-identify as nationals of their respective member states. (See Figure 1.)

According to Eurobarometer, in 2019 an average of 88 percent of respondents—including U.K. ones at the time—self-identified as exclusively a national of their country (33 percent) or first as one and then as European (55 percent). This level has been stable since the first such poll in 1992, when it was 86 percent, though with 38 percent seeing themselves as a country national only among the then 12 member states. In 2019, 31 percent in these 12 countries10 saw themselves as a national only and 57 percent as a national and then European, suggesting a very gradual shift among long-term EU members to a more European self-identification.

- 7The concept was articulated early by Henry Morgenthau, but notions that rulers operate under different moral settings than regular individuals go back to at least Machiavelli and Plato.

- 8Henry Morgenthau. “Another ‘Great Debate’: The National Interest of the United States,” The American Political Science Review, 46(4), 1952.

- 9Eurostat, Government expenditure on defence, 2021.

- 10In contrast to the other EU aggregates, this is a simple mathematical country average of the EU12, not considering different country population weights or sample sizes.

According to Eurobarometer, in 2019 an average of 88 percent of respondents—including U.K. ones at the time—self-identified as exclusively a national of their country (33 percent) or first as one and then as European (55 percent).

EurobarometerIt is the aspiration of this paper and of the European Interest(s) project to facilitate this shift further. This slow historical movement during a period in which a majority of EU members introduced, for instance, a common currency, EU citizenship, and open internal borders is, however, an important reality check for what can be achieved. Elected European leaders choosing today to pursue wholly or predominantly national interests at the European level would still have to do so in accordance with the primarily national self-identification of very large majorities of their populations.

Yet, even if one adopts the narrowest “physical self-preservation” definition of the national interest, the future value of the NATO security guarantee provided de facto to the entirety of the EU remains compromised—even after the election of Joe Biden—by the absence of a foreign and security policy consensus between the United States’ two main parties. The lack of a true community of values between almost all EU members and a Republican Party continuing to offer a Trumpian political platform makes it clear that outsourcing the physical self-preservation of EU members to NATO and the United States may not be sustainable in the future. Recent political developments in the United States therefore compel EU leaders to increasingly contemplate common interests associated with securing their countries’ physically.

More importantly, particularly in pluralistic polities where voters’ self-identification continues to be overwhelmingly at the national level, EU policymakers with finite resources and attention spans face hard choices among many competing interests of great importance. It is necessary to prioritize among them and a hierarchy of interests must be established. There will consequently be many important policy issues that are not European interests, in the definition adopted here. Inspired by the traditional concept of national interest, this paper slightly modifies the definition offered by Graham Allison and Robert Blackwill11 and defines European interests as those “vital” to the EU, meaning they are indispensable, or essential to the existence or continuance of the EU.

In the United States, during the Civil War in 1861–1865 union troops decisively settled the issue of whether secession was possible or not. The EU’s lack of full political union and of its own military capabilities, and the consequent inability to physically enforce its territorial integrity against such a threat has important implications for the scope of the EU’s vital interests. It renders the EU an inherently more fragile entity than a country enjoying a full monopoly on the legitimate use of physical force within its territory.12

Brexit and the ability of member states to leave the union, based on the EU Treaty’s Article 50, “in accordance with [their] own constitutional requirements” make the vital interests of the EU about much more than deterring or defeating internal or external physical threats. It creates the need for the EU to secure an acceptable normal level of functioning to preempt, or at least minimize the risk of, any further departure of members. The EU’s principal democratic political legitimacy and accountability remains anchored in member states, national identities, and political processes overwhelmingly conducted through national language and national media. It is therefore crucial for the EU to work, according to its own foundational values, to avoid the creation of political conditions in member states that could lead to public demands to exit the EU. This need for democratic political self-preservation will be a recurring theme in defining European interests.

This is a far broader notion of vital European interests than just physical self-preservation. It approximates another historical definition of the national interest often used in the United States, namely to “preserve the United States as a free nation with our fundamental institutions and values intact.”13 The EU equivalent would define European interests as entailing the preservation of the EU as a well-functioning entity with its fundamental institutions and democratic values intact.

This goal cannot be exclusively or even principally concerned with foreign policy, external EU representation, or the international conditions enhancing this outcome. In an entity with split sovereignty, with the possibility of voluntary exit of members, and in which members retain full control over most aspects of the state apparatus, safeguarding a well-functioning EU instead will often concern “domestic” European matters and how EU membership constrains or enables members’ actions.

Deciding what constitutes the acceptable normal functioning level of the EU is not straightforward, given its unique hybrid status as part state, part international organization and its innate experimental nature. The EU’s ability to institutionally innovate since its foundation in 1957 is testament to the ability of its leaders to identify critical weaknesses and overcome them. The early decades of EU integration were driven by the historical desire to overcome Franco-German enmity and to secure peace and prosperity in non-communist Western Europe. Since the end of the Cold War, major EU institutional reforms have been driven by the urgent need to respond to external and internal events. The Maastricht Treaty and the launch of the common currency were necessitated by the geopolitical shock of German reunification. And since the early 1990s the EU’s institutional design has proven simultaneously unstable and flexible, as recent crises have illustrated how the political compromises that enabled the deepening integration of the Maastricht Treaty were ultimately unsustainable. The adoption of a de facto monetary-only Economic and Monetary Union with an alleged “no bailouts clause” proved to be a deficient design of the common currency during the euro sovereign debt crisis after 2010. The creation by euro area members of the European Stability Mechanism (ESM) and the European Banking Union subsequently alleviated some of the most pressing institutional design flaws in the Maastricht Treaty for the common currency. In doing so, leaders acted in their countries’ interest and in the common European interest to help preserve the EU.14 Thus, EU actions revealed that preserving the common currency is a core European interest and that the euro is one of the fundamental EU institutions that must be kept intact.

One way of identifying the EU’s future vital interests hence lies in contemplating its current institutional deficiencies and fault lines that might require further redesign for the union to persist. Future necessary institutional reforms may or may not require outright treaty changes, as the coronavirus pandemic has again showed how flexible the existing legal framework is once vital interests are at stake and the political will to act is present. Reforms and institutional innovation will, however, invariably necessitate the approval of all member states. The ability of certain policy decisions to command unanimity suggests a revealed hierarchy of interests in their priorities. If a far-reaching decision changing the EU institutional setup commands the support of all member states, arguably it represents a shared vital EU interest rising above the national interests.

Other instances not concerning institutional reform where all EU members come together in sustained backing of a policy also potentially reveal how a similar broadly supported European interest is at stake. The unity exhibited by the 27 other members in the Brexit negotiations with the United Kingdom after 2016 revealed their shared interest in ensuring that the integrity of the internal market and the EU’s legal order remains intact, and also that Brexit would not prove an economic benefit to the United Kingdom to preempt opposition to EU membership growing in the remaining members.

- 11Graham T. Allison and Robert Blackwill, America’s National Interest: A Report from The Commission on America’s National Interests, 2000, p. 12.

- 12A monopoly on the legitimate use of force within its territory is a defining characteristic of the modern state, as described by Max Weber in H. H. Gerth and C. Wright Mills (Eds. and Trans.), From Max Weber: Essays in Sociology, Oxford University Press, 1946.

- 13Allison and Blackwill, America’s National Interest, p. 14.

- 14Chancellor Angela Merkel’s comments to the Bundestag at the time, “If the euro fails, then Europe fails”, captures the sentiment well. Der Spiegel, “Merkel Says EU Must Be Bound Closer Together,” September 7, 2011.

The European Interest(s) Project

The project aims to reform and rejuvenate the European debate. Ultimately, we want to provide decision makers and other protagonists with a new concept and narrative in their struggle over the future of Europe.

Crisis Pragmatism and the Drivers of Common Interests

A broad demarcation of European interests as those securing the preservation of the EU as a well-functioning entity with its fundamental institutions and democratic values intact is in some ways conservative, seeking to preserve the EU as it exists. At the same time, domestic democratic processes, technology, and the geopolitical environment in which the EU operates change over time, promoting new properties required to keep the union functioning well and demoting or eliminating other ones. Thus, it is no longer the common interest in keeping the Soviet Union at bay or France and Germany from fighting that binds the EU together and facilitates its proper function. In the 2020s, European interests are clearly different from what they were during the EU’s early decades.

An important decision must be taken when contemplating motivating factors for European interests today. Given its hybrid nature, the EU has a very large global economic weight and influence, but relatively few traditional hard-power assets of its own and little geopolitical influence beyond that exerted by its member states. One way to view the EU is as being on a gradual pathway to eventual full statehood, complete political integration, and economic and political power—the “ever closer union among the peoples of Europe” articulated in the Treaty of Rome. In this “federalist” vision, European interests would invariably tend to promote additional integration and the EU taking over evermore state-like capabilities.

Another viewpoint holds that the EU is sui generis and, due to prohibitive democratic obstacles in achieving full political integration, will always retain its hybrid nature. This paper endorses the latter view and thus treats European interests and motivations as striving to make the EU not “an ever closer” union but instead “a more perfect” one.15

That no assumption of or requirement for “more Europe” exists in motivations for common European interests is important in the light of recent crisis-driven EU integration. The additional euro area institutional integration associated with the creation of the ESM and the implementation of the Banking Union as part of the response to the debt crisis after 2010 has been discussed above. European institutions taking over new policy responsibilities comprised the core of the response and the defense of vital European interests at stake.16

The same pattern was repeated in 2014–2015 when the EU faced a sudden dramatic increase of migrants claiming refugee status from entry points in North Africa and especially from Turkey. The common EU response was more incoherent and partial than that eventually witnessed during the euro debt crisis. Yet, among other things the common EU budget was mobilized to finance an agreement with Turkey and the European Border and Coast Guard Agency (the EU’s first uniformed personnel unit) was created.17 Again an expansion of EU-level capacities and responsibilities constituted the most important aspects of the response to the crisis.

The same has been true since the start of the coronavirus pandemic in early 2020. Not only was the European Commission tasked with securing the critically important supply of vaccines to the entire union, the EU also adopted a common fiscal response, including novel joint debt issuance by the EU and explicit fiscal transfers assumed in the disbursement. Arguably, the common EU response to the pandemic has witnessed the largest jump in new integration—this time fiscal—since the adoption of the Maastricht Treaty.

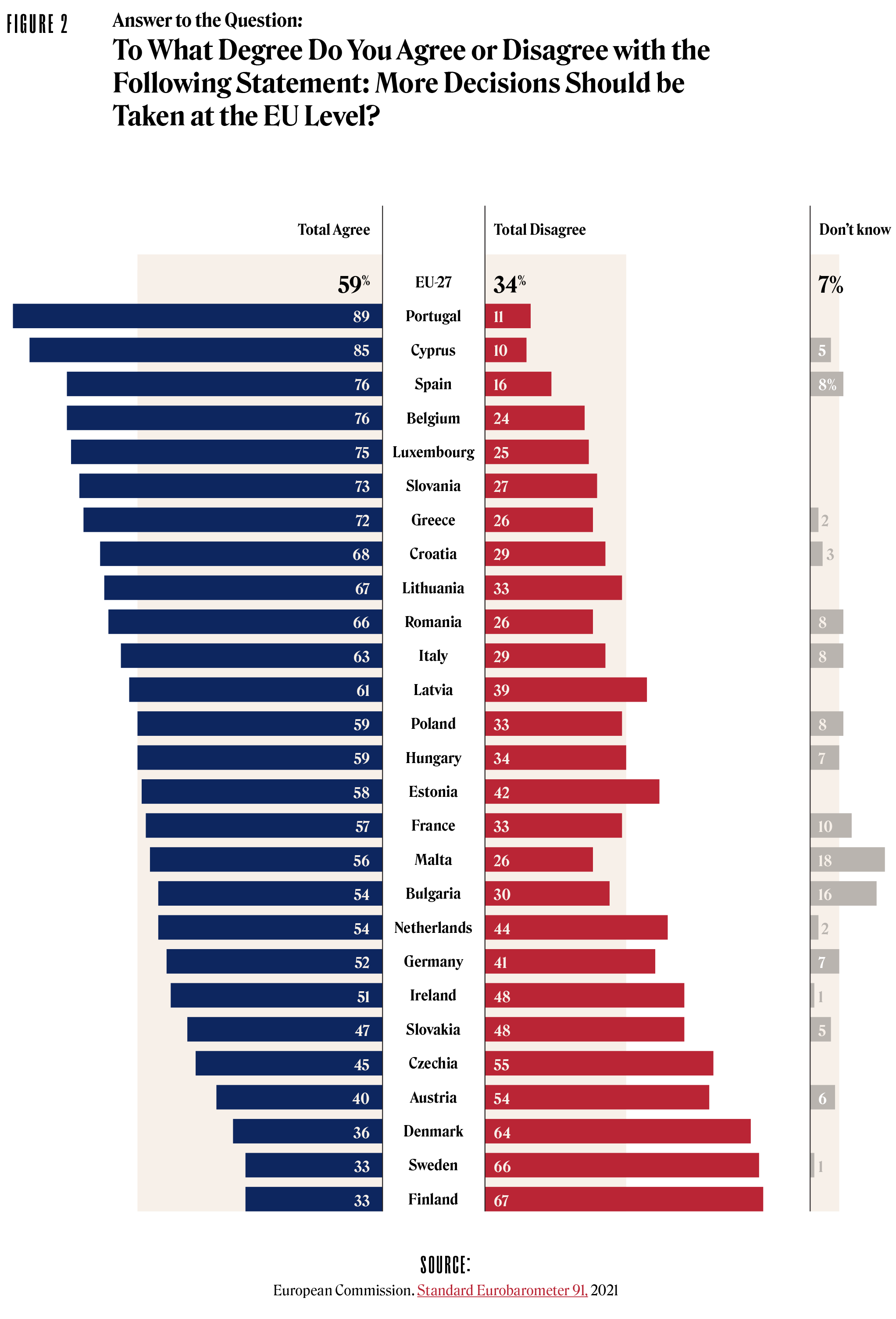

The last decade of EU crisis-driven policymaking hence suggests that “more Europe” will often be the manner in which European interests are defended by EU leaders. For the member states and their populations, a stage of integration may now have been reached in which the departure of a member or the outright collapse of the EU is now, if not democratically impossible, at least significantly less likely to garner support than in the past. The perceived adverse impact of Brexit on the United Kingdom will also have played a role recently in increasing public trust in the EU and swaying often large majorities in all EU members (bar Bulgaria) against leaving.18 However, polling also indicates even if a majority of all EU residents today support the abstract notion that “more decisions should be taken at the EU level,” large majorities in some member states oppose this. (See Figure 2).

A strategy of seeking more EU integration through accumulated crisis responses hence risks alienating majorities of the public in the long run in at least some member states, even if EU leaders successfully act in the common European interest in each crisis. Voters’ political preferences are often inconsistent; they may support particular steps taken in the European interest in the heat of a crisis, while opposing the resulting broader centralization of the EU.

At the very least, crisis-driven integration raises the political threshold for when the population in many member states can be asked at a referendum to approve, for instance, future changes to the EU Treaty. Given the constitutional requirements in several member states for referenda to approve any additional material transfer of sovereignty to the EU, this creates political tension between what is needed to stop a crisis and what voters may be persuaded to approve. A tendency for voters to prioritize more EU integration in a crisis but less in calmer political circumstances incentivizes EU governments to hold second referenda about largely the same question to “overcome” the crisis created by an initial popular rejection.19 This is a highly risky political strategy to sustain the democratic legitimacy of European integration and changes to EU treaties, as it is fundamentally at odds with free, open, and uncoerced democratic popular deliberation.20 Ironically, by acting in the European interest in the short term by adding “more Europe” in this way, leaders may compound the notion of a democratic deficit in the EU in the longer run.

Even if “more Europe” is repeatedly added to the EU institutional design, this paper’s rejection of the path of “ever closer union” and eventual full political union has consequences. An EU without full political union will never in an independent capacity acquire the full range of military and national security assets commensurate with its wealth and technological capabilities. Member states will invariably keep for themselves many such assets, subject only to national sovereignty. This does not mean that the EU cannot dramatically expand its military and national security assets from today’s extremely low levels—only that it will continue to punch well below its economic weight in terms of hard power and geopolitical influence. This political reality will inform the identification of specific European interests in this paper, and invariably serve to limit their geographic scope and traditional military and national security focus.21 A possible future disappearance of the traditional U.S. security guarantee provided via NATO for the EU would self-evidently compel member states and the EU itself to dramatically reevaluate the desired scope of their own military capabilities. Such a development could, even in the absence of a full political union, potentially see the EU’s independent military capabilities expand dramatically and fast. But for now, although the traditional territorial integrity and security of its member states is naturally an interest of the EU, it is left out of this discussion as it is not the EU (nor its member states alone) that carries primary responsibility for this core interest but member states as well as NATO and the United States.

Even if “more Europe” is repeatedly added to the EU institutional design, this paper’s rejection of the path of “ever closer union” and eventual full political union has consequences.

Finally, beyond acting to avoid systemic EU crises, several general and perpetual motivational categories of European interests exist.

First, the EU will want to be able to resist the effects of other countries’ extra-territorial policies outside the national security and military realm. This includes the economic effects of U.S. sanctions against European firms operating in third countries (like Iran) in compliance with EU and member-state laws but in breach of extra-territorial U.S. ones.22 It also includes the economic distortive effects of other countries’ domestic government subsidies for companies that make them better financially able to compete in global markets, including in the EU.23 Some cyber intrusions for industrial espionage or other hybrid threats24 carried out by foreign government-linked or sanctioned entities could also qualify, though cyber security in general remains predominantly a national law-enforcement issue or explicitly in the realm of national security and NATO for EU members of the alliance.

Second, common European interests are today negatively motivated by the risk of EU irrelevance in global affairs unless member states cooperate. As market-economy principles have spread around the world and levelled inter-state economic differences, the EU’s share of global GDP has and will continue to decline. Member states moreover have experienced rapidly declining fertility levels earlier than most countries of the world. As a result, the EU’s share of the global population has declined significantly since 1957.25 With smaller shares of output and smaller shares of the world’s consumers, even the largest EU members face the risk of a decline in their global influence and even their ability to sets domestic regulatory standards. All EU members stand to lose parts of their freedom of action or sovereignty to faster-growing economies around the world unless they continue to cooperate closely.

Third, EU member states have important positive motivations to pool their resources and work closely together toward common European interests in the nature of many of the principal challenges they currently face. Whether with regard to the coronavirus pandemic, to climate change and the required energy transition, to digitalization and workplace transformation, or to irregular migration and organized crime, credible and sustainable solutions are beyond the capabilities of any individual member state and can only be found at the EU level. If EU governments want solutions to the challenges they face, they are compelled to work together by voting publics that demand solutions to this category of problems.26

Defining Vital European Interests

This paper argues that adapting the concept of the national interest to the European level entails recognizing that the EU is a more fragile entity than most democratic states, and that this requires particular attention is constantly given to ensuring that the EU functions well with its fundamental institutions and democratic values intact. This will guard against member states wishing to leave the union and help validate for voters that additional integration initiatives taken in response to crises are in their long-term interest too.

The next step is to lay out what issues rise to the level of vital importance for the EU and all its member states. It is possible to imagine countless potential threats to a well-functioning EU with its fundamental institutions and democratic values intact. Thus, the list of potential European interests is very long—and the next systemic crisis may add to it.

It is argued below that six distinct European interests exist. Some are simultaneously of a domestic and an external nature for the EU, and their designation as being domestically or externally oriented is to indicate their predominant orientation. These interests will also overlap and may occasionally come into conflict with each other.

Domestically Oriented European Interests

Preserving Democratic Values and Rule of Law in the EU

The EU’s founding document, the EU Treaty, specifies at the outset in its Common Provisions the union’s foundational and perpetual values.27 It is thus a European interest to secure at all levels of government within the EU the continued adherence to the values laid out in its Article 2:

The Union is founded on the values of respect for human dignity, freedom, democracy, equality, the rule of law and respect for human rights, including the rights of persons belonging to minorities. These values are common to the Member States in a society in which pluralism, non-discrimination, tolerance, justice, solidarity and equality between women and men prevail.

The Union is founded on the values of respect for human dignity, freedom, democracy, equality, the rule of law and respect for human rights, including the rights of persons belonging to minorities.

Failure to do so would jeopardize the essential coherence of the EU and over time likely lead to the departure of those member states moving towards autocracy or those wishing to continue to adhere to these values. Since the member states most keen on securing these democratic values and the rule of law are also often net financial contributors to the expanding EU budget, denial of budgetary transfers to those in violation of the values laid out in Article 2 would seem a plausible way to address this problem and be in the European interest.

Maintaining Broadly Similar Economic Trajectories among EU Member States and Regions

The EU operates with a division of competences that leaves to member states any competence not bestowed by the EU Treaty. The treaty specifies several areas where the EU enjoys “exclusive competences”: the customs union, trade policy, cross-border competition policy, monetary policy in the euro area, and marine biology. It further stipulates areas of “shared competences,” or more accurately where members exercise their competences where the EU does not, or has decided not to, exercise its competence. These include the internal market, social policy, regional policy, agriculture and fishing, environment and climate, consumer protection, transport, trans-European networks, energy, justice, public health and safety, research, and development and humanitarian aid. The treaty also identifies policy areas in which member states retain all powers and the EU has only “supportive competences,” including health, industry, culture, tourism, education, civil protection, and public administration. In the case of health, however, the coronavirus pandemic has highlighted that in a crisis common decisions can also be taken in an area of only supportive EU competences.

Member states remain the most influential economic actors in the EU. They are principally responsible for domestic economic developments and accountable to voters for their performance. As noted above, there is a limited number of—in several cases external—economic issues in which the EU exerts exclusive powers. Yet, as the EU economies have integrated, significant cross-border economic effects exist today. And, more importantly, in the event of a sudden or gradual economic underperformance in a member state or region, the well-functioning status of the EU is inevitably threatened by the potential this has for strengthening of centrifugal and/or nationalist populist political forces. This makes satisfactory economic performance in, or at least the prevention of excessive economic divergences among, all member states also a European interest.

The EU’s structural funds have from the beginning had a significant component focused on long-term investment-based growth and economic development, entailing fiscal transfers among member states. Recent crisis-mitigation measures adopted after the euro area debt crisis and the coronavirus pandemic go significantly further. The euro area now has in the ESM the capacity to provide conditional financial assistance to member states in acute economic crises, while the coronavirus Recovery and Resilience Fund has set the precedent that commonly financed EU debt is part of the solution to collectively experienced economic crises. Thus, the EU already provides member states with frequently sizable economic assistance to promote a degree of economic convergence.

As witnessed in the years after 2010, it is a core European interest to preserve the euro. Failure to do so would push many members no longer able to remain in the euro, due to low productivity and inefficient public administration, toward dramatically lower standards of living. But it is also in the European interest to move beyond sustaining the common currency and to continue to strengthen fiscal, monetary, and broader economic ties in the EU. This is required to avoid politically damaging divergences in economic trajectories among members and regions. This will also in the post-coronavirus era help ensure that all EU residents have access to a similarly acceptable level of pandemic protection and healthcare services.

However, reflecting the primacy of member states in most economic areas and the incomplete nature of the EU political integration, EU financial transfers must at all times be subject to the relevant degree of policy conditionality to make such transfers politically legitimate.

Avoiding excessive economic differences among member states and regions is reflected in the political desire to limit general inequality in European societies. This desire for a “social Europe” sees members on average maintain the highest levels of government “social protection” expenditures in the world at 19.3 percent of GDP in 2019.28 It is also among the most important aspects of European integration for large majorities of Europeans,29 and ranked by them as the most important priority for EU institutions.30 Ensuring that member states and regions have comparable economic trajectories to facilitate the delivery of a “social Europe” is therefore a widely supported European interest.

Securing the EU’s Role as a Global Leader in the Fight against Climate Change

A European public good—for example, traffic and food safety standards, environmental protection, statistics, freely available innovation, or herd immunity—is not necessarily a vital European interest. However, at least one such public good is the protection and mitigation from climate change, due to the physical threat its non-provision poses for Europeans and to the political cost to the EU of ignoring the widespread public support it commands. This is the successful fight against climate change. The EU’s territory and residents are under direct physical threat from many manifestations of climate change, including more frequent and fierce floods, droughts, forest fires, or storms. Moreover, the increasingly rapid and fundamental transition of most modern economic activity toward zero emissions, which is required to combat climate change, can in the EU’s deeply integrated economy only be carried out with a very high degree of collaboration at the union level. And, with the growing consensus among its publics in support of forceful action against climate change, failure to act accordingly would damage and delegitimize the EU. If the EU cannot effectively help fight a challenge like climate change, what would its purpose be? How would especially young people in the EU, a group particularly committed to addressing this challenge, remain engaged with or attach any value to the EU if it does not take aggressive measures to address the climate crisis?

Climate change is a global threat and the EU, though historically a major emitter, is now responsible for about 8 percent in 2019 of total emissions.31 To successfully address climate change, the EU must therefore maintain its global leadership role and exert political, technological, and financial leadership in pursuing global solutions. Doing so credibly, however, remains overwhelmingly a domestic economic, political, and technological challenge and interest for the EU. Only by rapidly and drastically reducing its own carbon emissions will the EU maintain its current prominent global role.

Upholding a Credibly and Uniformly Controlled EU External Border

Explicit military defense of the territorial integrity of the EU is the responsibility of member states and often NATO. Maintaining an adequate and uniform level of external border control, however, has since 2015 been an increasingly shared responsibility between the EU and member states. There are several reasons why this policy area is a vital European interest.

First, events in 2014–2015 showed the speed at which temporary uncontrolled migration movements into the EU can change the political dynamics in many members and empower nationalist political parties. The potential for such parties to take power in more member states is the antithesis of a well-functioning EU.

Second, the use of EU budget resources to secure an agreement with Turkey to block migration into the EU has led to other neighbors utilizing the possibility of such movements to gain political leverage, as seen in the recent actions of Belarus and Morocco. Unless uniform border management is implemented via EU-level actions across the entire external border of the union, such blackmail attempts will likely multiply.

Third, migratory patterns into the EU are likely to continue to rise in the coming decades, as it remains the closest affluent region to the world’s last remaining high-fertility region in Africa. And several of the EU’s neighbors are likely to witness dramatic economic dislocation from climate change as well as from the EU’s move toward decarbonization by 2050.

Fourth, as recently illustrated again by pandemic-related border closures, the continued seamless functioning of the EU’s borderless internal market is crucial. The ability to maintain open internal borders (at least in the Schengen Area) and to deter member states from implementing even temporary border closures is unambiguously a European interest.

This requires that the EU’s entire external borders are credibly and uniformly controlled. Achieving this will further help prevent that a “weakest link member” experiences large, opportunistic migrant movements. Such a development could cause the national government concerned to turn to excessive force and possibly illegal means to reduce inward migration. This will be beneficial to migrants too. As all EU members are signatories to the 1951 UN Refugee Convention, which guarantees the right to apply for political asylum, a credibly and uniformly controlled EU external borders may also require closer collaboration among members in processing such applications and in migration regulation more generally.

Externally Oriented European Interests

Maintaining Constructive and Principled Relations with EU Neighbors

An EU that is unlikely to evolve into a full political union, and hence to ever acquire full or majority responsibility for members’ military or national security interests, is also not likely to be able to project its independent political will much beyond its own borders. It will simply not have the capacities to do so. Consequently, it is in the EU’s vicinity that vital external European interests are found. The EU Treaty foresaw this situation and specifies that the EU’s neighbors are subject to special EU interest and relations. Article 8 states:

- The Union shall develop a special relationship with neighbouring countries, aiming to establish an area of prosperity and good neighbourliness, founded on the values of the Union and characterised by close and peaceful relations based on cooperation.

- For the purposes of paragraph 1, the Union may conclude specific agreements with the countries concerned. These agreements may contain reciprocal rights and obligations as well as the possibility of undertaking activities jointly. Their implementation shall be the subject of periodic consultation.

Constructive and principled relations with the EU’s neighbors were in the past partly relevant also with an eye toward eventual EU expansion. But, even as the EU has reached its greatest plausible geographic and political boundaries, relations with its neighbors remain of vital common importance. Article 21 makes it clear that the EU shall seek to externally advance its democratic and rule of law values. This is invariably most relevant for many of the EU’s neighbors. Article 21 states:

- The Union’s action on the international scene shall be guided by the principles which have inspired its own creation, development and enlargement, and which it seeks to advance in the wider world [emphasis added]: democracy, the rule of law, the universality and indivisibility of human rights and fundamental freedoms, respect for human dignity, the principles of equality and solidarity, and respect for the principles of the United Nations Charter and international law.

The Union shall seek to develop relations and build partnerships with third countries, and international, regional or global organisations which share the principles referred to in the first subparagraph. It shall promote multilateral solutions to common problems, in particular in the framework of the United Nations. - The Union shall define and pursue common policies and actions, and shall work for a high degree of cooperation in all fields of international relations, in order to:

- safeguard its values, fundamental interests, security, independence and integrity;

- consolidate and support democracy, the rule of law, human rights and the principles of international law;

- preserve peace, prevent conflicts and strengthen international security, in accordance with the purposes and principles of the United Nations Charter, with the principles of the Helsinki Final Act and with the aims of the Charter of Paris, including those relating to external borders;

- foster the sustainable economic, social and environmental development of developing countries, with the primary aim of eradicating poverty;

- encourage the integration of all countries into the world economy, including through the progressive abolition of restrictions on international trade;

- help develop international measures to preserve and improve the quality of the environment and the sustainable management of global natural resources, in order to ensure sustainable development;

- assist populations, countries and regions confronting natural or man-made disasters; and

- promote an international system based on stronger multilateral cooperation and good global governance.

The vital interest in constructive and principled relations with neighbors also follows directly from the importance of managing EU external borders well, just as active cross-border engagement on law-enforcement issues will benefit the entire EU. Recognition of the vital nature for the EU of principled relations with neighbors, as well as credibly and uniformly controlled external borders, will reduce the risk of member states being subject to political and/or economic pressure from a neighbor. A neighbor would recognize that an EU prioritizing collective relations with neighbors would regard any quarrel this neighbor has with an individual member as a quarrel with the entire EU. Principled neighborly relations will thus often also be expressed by quick solidarity and unity from the entire EU in any member’s disputes with a neighbor of the EU.

The European interest in maintaining sound relations with its neighbors and the pursuit of democracy extends to the need for the EU to strive to prevent the emergence of a major autocratic competitor on its immediate border. This has in recent years made relations with Russia and Turkey taxing.

Last, the importance of constructive relations with neighbors, their future challenges related demographic and climate change, and the EU’s limited political resources risks making the pursuit of EU political strategies outside the economic realm further from home a dangerous distraction. There are no vital European interests at stake in, for instance, the Indo-Pacific region.32

Sustaining a Cooperative International System and Sustaining Good Relations with Like-minded Third Countries

The EU Treaty’s Article 21 is very explicit in tasking the EU to promote multilateral relations when at all possible. The inspiration in Article 21 for the EU Council’s 2016 approximate definition of the EU strategic autonomy concept cited at the beginning of this paper is obvious. This raises the question of whether European interests must comply with the global norms articulated in the UN Charter and related conventions. The answer provided in Article 21 is affirmative. Externally oriented European interests must adhere to these norms to promote a cooperative international system.

An entity like the EU, unlikely to ever be fully sovereign and limited in the scope of its hard power, has an interest in a rules-based cooperative international system. It also faces limitations in the military and national security responsibilities it can successfully take on, and in the related European interests to which it can aspire.

As the EU, absent full political integration, will remain a predominantly economic power, pursuing trade, investment, broader regulatory, and climate-change objectives across the world will continue to be the preferred manner in which it projects its global influence. Doing so with the greatest effect will require the EU to temper its economic pursuits with other aspects of its interests.

The importance placed in Article 21 on democracy, the rule of law, and human rights commands that the EU place particular importance on maintaining fruitful relations with like-minded democracies, which are also the most likely other supporters of a rules-based cooperative international system. This focus is also demanded by the current authoritarian challenge posed by China in global political and economic affairs, but it should not dictate limiting interactions with China or other non-democratic states. Only countries, like North Korea, that oppose the cooperative international system in its entirety must be ostracized by the EU in its external activities.

Particular weight should be placed on maintaining good political and economic relations with the United States, given its historical importance as the principal security guarantor for Western Europe and the majority of EU members. However, this cannot sway the EU from always defending its common interests against U.S. national self-interest. It should though be a crucial factor that the EU and the United States working together offers a decisive economic and political counterweight to any plausible global alliance of non-democratic nations.

The need for close collaboration among like-minded countries, and particularly between the EU and the United States is particularly relevant when setting industrial standards and developing entirely new technologies. European and U.S. regulatory philosophies are often fundamentally different, but the two economies together continue to account by far for the world’s largest “democratic marketplace” and the only one that rivals the purchasing power of the Chinese market. Size and economies of scale matter in global supply decisions. The EU and the United States, apart from having a clear interest in remaining at the global technological frontier, have a clear interest in ensuring that global companies continue have the financial incentive to manufacture their products to first and foremost the standards set by democratic governments.

A European Interest Benchmark

Defining here what European interests are aims to assist policymakers in mobilizing public support for implementing EU policies in accordance with the prescriptions laid out in the previous section. Doing so will aid the coherence and quality of EU policymaking. A key enabling factor for such a constructive outcome is the assertion here that clearly defining European interests that should guide EU policies will facilitate engagement with civil society groups, NGOs, grassroot organizations, and individual Europeans.

At this point in time, shortly after the launch of the Conference for the Future of Europe, it is hoped that the concept of European interests as guidelines for and occasional restraints on EU policymaking, can serve as important constructive input to the deliberations of the conference. On the other hand, the European interest concept is not helpful for putting together detailed proposals for EU institutional reform or decision making procedures that at least some envision the conference yielding.

Given the frequency with which European policymakers’ claim justification for their actions with reference to a European interest, the coherent and lucid definition offered in this paper can serve to protect the notion of the European interest against deceitful rhetorical use of it by policymakers. The six categories into which European interests are divided can form a “European Interest Benchmark” with which to debunk such spurious political claims, and a standard against which policy proposals and decisions across the EU are evaluated.

First, a rolling assessment would entail establishing whether a member state’s action, a national or EU law, a European Commission decision, a speech by a senior policymaker, a government announcement, or any other manifestation of EU policymaking falls within one of the six categories. If it does not, this would not mean that it is not important. It would merely mean that it does not pertain to a vital European interest without which the preservation of the EU as a well-functioning entity with its fundamental institutions and democratic values intact may not be possible.

While the six categories of European interests defined here are hardly limiting in potential scope, many issues would not be included. The completion of the Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline might, for instance, be an important issue for many in Germany and even, in the words of Germany’s Economic Minister Peter Altmaier, “crucially important”33 for the EU’s energy supply. But neither makes its completion a European interest.

Second, if a policy action is found to fall within one of the six categories, its content must be assessed against the details and spirit of the European interest involved. This will be an at least partly normative process, as the wording of a policy proposal or statement or the practical impact of its implementation are assessed to assist the well-functioning of the EU with its fundamental institutions and democratic values intact. If they do not, a claim to be acting in the European interest must be rejected.

European interests must at the same time be understood as being distinct from the statements and policies pursued toward their fulfilment and identifying something as a European interest cannot settle debates over competing policy proposals within the subject area. That something is a European interest instead merely calls for detailed analyses to establish relevant policy options, their costs and benefits, and their chance of success. An always complicating factor in the latter is the passage of time, which may through unintended consequences undo any initial positive effects of even the most carefully thought out and implemented policy.

- 15The latter term is borrowed from the preamble to the U.S. Constitution.

- 16This involved creating new institutions and significant changes to existing euro area ones. The ESM was established for conditional financial rescues, the Banking Union took over most financial supervision, and the European Central Bank agreed to, with EuroGroup approval, to conditionally purchase a euro area member’s debt in crises situations in Outright Monetary Transactions.

- 17The broader reform of EU immigration and refugee reception policies (the Dublin System), which could potentially significantly after members’ responsibilities in this area, has for that reason not yet been agreed.

- 18In a 2021 survey, roughly two-thirds of respondents said they disagreed that their country would fare better outside the EU. Eurobarometer, Standard Eurobarometer 94—Winter 2020-2021, 2021. Greece’s experience suggests that a point of integration “no return” is reached with the adoption of the euro. Despite suffering the worst economic recession of any EU member in decades and rejecting “further austerity and Troika conditionality” in a referendum, voters in September 2015 overwhelmingly supported parties committed to the euro and the associated conditionality from the international community.

- 19This dynamic was visible in Denmark in 1992-1993 following the rejection of the Maastricht Treaty and in Ireland in 2008-2009 following the rejection of the Lisbon Treaty in referenda. In both cases, minor changes were agreed to the EU Treaty framework applicable to the two countries, and voters then approved the new EU Treaty.

- 20The existence of large majorities against “more decisions taken at the EU level” in countries, such as Denmark and Sweden, that have constitutional requirements for referenda to approve EU Treaty changes affecting national sovereignty aggravates this risk.

- 21A member may have geographically broader national interests than the EU. This is particularly the case for those still retaining overseas territories and with significant military and security assets. France—the EU’s only nuclear power and with territories in the Caribbean, South America, and the Pacific and Indian Oceans—is the prime example.

- 22In 2019 seven member states and Norway and the United Kingdom in 2019 INSTEX, a Paris-based special-purpose vehicle aimed at facilitating legitimate (under EU laws) trade in food, agricultural equipment, medicine, and medical supplies between the EU and Iran by circumventing the traditional financial channels utilized by the United States to impose its extra-territorial sanctions. Overall, however, the EU has struggled to counter weaponized U.S. sanctions, due to the importance of the dollar in the international financial system, and the greater weight of the U.S. market, relative to that of the sanctioned economy, for most relevant EU businesses.

- 23The European Commission in May 2021 proposed a new regulation to prevent this kind of distortive foreign subsides from affecting the Internal Market’s level playing field. European Commission, Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on foreign subsidies distorting the internal market, 2021.

- 24Hybrid threats generally refer to non-military tactics including propaganda, online spreading of misinformation, deception, or outright sabotage. Hybrid methods often blur the distinction between war and peace but may involve military assets.

- 25Fertility rates remains very low in some member states but have rebounded or remained relatively high in others, while they are declining in many other countries globally, including in many Asian one to levels far below the EU average. The decline in the EU’s share of the global population has hence peaked and could, once inward migration is factored in, soon stop.

- 26In one survey in the fall of 2020, European respondents ranked the top global challenges to the future of the EU as climate change, health risks, and immigration. Eurobarometer, Special Eurobarometer Future of Europe, 2021.

- 27Treaty on European Union.

- 28Eurostat, Government Expenditure on Social Protection, 2021.

- 29In one survey, 88 percent of European respondents said a “Social Europe” (“Europe that cares for equal opportunities, access to the labor market, fair working conditions, and social protection and inclusion”) was important to them personally. Eurobarometer, Special Eurobarometer 509—Social Issues, 2021.

- 30In one survey, 48 percent of European respondents ranked “Measures to reduce poverty and social inequality” as the main priority for EU institutions, making it the top issue. Kantar (2020). A Glimpse of Certainty in Uncertain Times.

- 31Our World in Data, CO2 emissions, undated.

- 32The EU Council in April 2021 nonetheless adopted a new EU strategy for cooperation in the Indo-Pacific.

- 33Deutsche Welle, “Nord Stream 2 ‘crucially important’ for EU energy security,” June 24, 2021.

References Used

Graham T. Allison, and Robert Blackwill, America’s National Interest: A Report from The Commission on America’s National Interests, 2000.

Council of the European Union, Council conclusions on an EU Strategy for cooperation in the Indo-Pacific, 2021.

Eurobarometer, Special Eurobarometer Future of Europe, 2021.

Eurobarometer, Standard Eurobarometer 94—Winter 2020-2021, 2021.

Eurobarometer, Special Eurobarometer 509—Social Issues, 2021.

European Commission, Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on foreign subsidies distorting the internal market, 2021.

European External Action Service, Shared Vision, Common Action: A Stronger Europe. A Global Strategy for the European Union’s Foreign and Security Policy, 2016.

European External Action Service, Scoping Paper: Preparation of the Strategic Compass, 2021.

Eurostat, Government Expenditure on Social Protection, 2021.

H.H. Gerth and C. Wright Mills (Eds. and Trans.). From Max Weber: Essays in Sociology, pp. 77128, New York: Oxford University Press, 1946.

Kantar, A Glimpse of Certainty in Uncertain Times, 2020.

Henry Morgenthau, “The Primacy of the National Interest,” The American Scholar, 18(2), 1949.

Henry Morgenthau, “Another ‘Great Debate’: The National Interest of the United States.” The American Political Science Review, 46(4), 1952.