Turkey’s Disengagement from the European Union

If the EU is to be a global power, however, a united front is a must. EU candidate countries can help in this effort. It is, after all, in their interest to align with the bloc’s policies, whether by supporting them in international forums or applying sanctions.

Almost all candidate countries do this already, but one major exception exists.

Turkey has refused to align with many EU policies as the bilateral relationship has soured over the last seven years. Brussels considered this a mere annoyance until the outbreak of war in Ukraine, when Turkey declined to adopt EU sanctions on Russia. Ankara initially justified its position by claiming an obligation to comply only with UN-imposed sanctions. A subsequent argument was a lack of EU consultations, but this ignores the way the EU functions: The bloc decides, and candidate countries follow.

Still, the slights have been mutual. Turkey was not invited last August to join Ukraine, Moldova, and Georgia in an informal EU foreign affairs meeting in Prague to discuss the war. This was unwise given Turkey’s critical geographic position. EU frustration was also apparent in a December 2022 European Council statement that confirmed Turkey “remained a candidate” but deeply regretted its “non-alignment with EU sanctions against Russia”. The statement also underlined the Council’s strong expectation that Ankara would “step up its alignment with EU Common Foreign and Security Policy positions and restrictive measures as a matter of utmost priority”. The European Commission, for its part, appointed a special international envoy to encourage third countries to enforce sanctions against Russia. It is unclear if Turkey will respond to these messages.

Turkey’s estrangement from EU foreign and security policy is not new, as the bloc’s annual country reports acknowledge. But it was not always this way.

Turkey became an EU candidate country at the Helsinki European Council in 1999 and began to align its policies with the EU acquis. The European Commission’s 2002 and 2003 Turkey report declared that the country continued to align its foreign and security policy with the EU’s. By 2004, though, the Commission began to paint a more nuanced picture, stating that Turkey’s position was overall satisfactory from the perspective of Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP) even if it was significantly less aligned with EU declarations than other candidate countries. This was particularly true for human rights, democracy, and issues related to Turkey's neighbors (Georgia, Azerbaijan, Iraq, and Ukraine) and some Islamic countries. The 2005 report remained encouraging, underlining positive development of relations between Turkey and Greece and improved relations with Syria.

By 2006, change was apparent. The EU blocked eight negotiating chapters due to non-compliance with applying customs union rules to all member states (Cyprus was the outlier). But the EU still noted that Turkey broadly aligned with the bloc's statements, declarations, and initiatives. Ankara sustained this policy notwithstanding German Chancellor Angela Merkel’s and French President Nicholas Sarkozy’s opposition to Turkish EU membership.

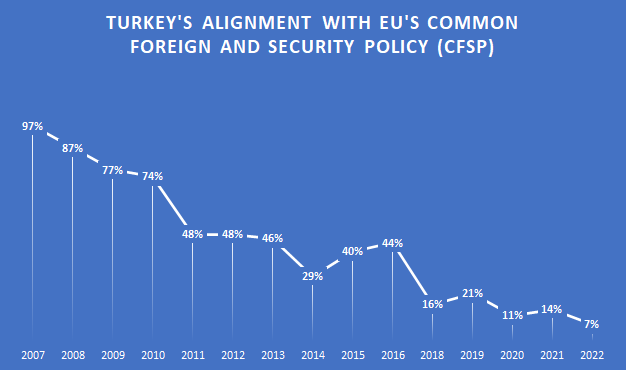

The 2007 report underlined Turkey’s alignment with the CFSP, supporting 45 out of 46 declarations, but progress declined after that. The downward trend has continued until today bar a small turnaround between 2014 and 2016.

The most recent 2022 report exposed a nadir: “Backsliding continued due to [Turkey’s] unilateral foreign policy being at odds with the EU priorities under the common foreign and security policy … notably due to its support for military actions in surrounding conflicts such as in Syria and Iraq, and lack of alignment with EU restrictive measures against Russia. … Turkey maintained a very low alignment rate of 7%.”

At the same time, a deteriorating economic situation spurred Turkey to mend ties with countries—Israel, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates—that it had alienated for some time. The same was not true for the West, particularly the EU. Consultations on international issues remained sparse and focused mainly on the bloc’s points of interest, such as illegal migration. But there was no concerted action. Foreign policy cooperation suffered alongside the political relationship. Most collaboration is now on hold until the outcome of Turkey’s June presidential and general election is known.

The EU’s prior stance on foreign policy cooperation with candidate countries does not augur well, regardless of the election results. The bloc’s problematic history of preferring discussion to coordination with third countries negates its influence. Agreement on all aspects of a particular issue may be unlikely, but convergence on at least some points would provide traction.

Turkey’s currently dormant relationship with the EU, however, threatens even this limited amount of progress. And its turbulent bilateral relationships with some EU member states, notably Greece, and France, is a further obstacle, despite all being NATO allies.

Some movement may occur if a new Turkish government brings back the rule of law, reestablishes fundamental freedoms, and lowers the harsh foreign policy rhetoric. In this case, the EU should find ways of meeting Turkey’s concerns on visa liberalization and modernizing their customs union to repair a critical relationship with a country that can act as a mediator between Ukraine and Russia. Only the latter benefits from Turkey’s continuing and growing disassociation with the West.

Every crisis is an opportunity as the established orders shifts. Finland’s and Sweden’s applications for NATO membership prove that this crisis is no exception. But the opportunity to improve EU-Turkish relations is more difficult to grasp. Ironically, a successful Russian invasion of Ukraine could have thrust the EU closer to a Turkey whose cooperation would have become more vital than it currently is. Ankara did, after all, play a key role, with the UN, in finalizing last summer’s grain export deal between Russia and Ukraine.

Even the recent formation of the European Political Community may be insufficient for bridging the gap and instigating proper foreign policy discussions between the EU and Turkey. The forum will need to be more than a talking shop if it is to have any real impact.

The world has always gone through major changes, but today’s usually occur more rapidly and on multiple fronts. International unity to meet global challenges is a rational manner of acting, but the inability of established multilateral institutions to address issues of concern to Turkey is disappointing. The persistent lack of urgency to fix that is too.

At such a watershed moment in international relations the EU and Turkey need each other more than ever.

Selim Yenel is the president of Global Relations Forum. He previously served as a diplomat, including as ambassador and permanent delegate of Turkey to the European Union and as undersecretary at the Ministry of EU Affairs.

The views and opinions expressed in the preceding text are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the positions of the German Marshall Fund of the United States.