A Year of Trump vs. Kim: Rhetoric Gone Nuclear

When Donald Trump took office a little more than a year ago, it was clear from the outset that the nuclear threat from North Korea would become a key foreign policy challenge during his tenure. But his response and the immediate escalation were unexpected. Security on the Korean peninsula has been causing sleepless nights for U.S. presidents since World War II. In the past few years Pyongyang’s efforts to attain improved nuclear and missile capabilities have clearly accelerated. The situation turned into a nightmare scenario for President Trump very early into his presidency when North Korea started successfully testing (or showcasing) intercontinental ballistic missiles. But the open confrontation that erupted between Washington, DC and Pyongyang has in fact two separate strands: rhetoric and policy.

Donald Trump’s statements concerning North Korea have been consistently bellicose. Almost 20 years ago he argued that the Kim regime’s strive for nuclear weapons poses a vital threat to the United States and should be addressed with pre-emptive military action if negotiations failed. Since taking office, in public speeches and via Twitter — his no-filter medium of choice for direct interaction with the world — Trump has engaged in an outright defamation contest with Kim Jong-un. A rather absurd interaction given the parameters: The 71-yr-old commander-in-chief of the most powerful military, head of state of the most potent economy, in a battle of insults with the 35-year old nuclear novice, totalitarian leader of one of the poorest countries in the world, isolated internationally, and economically strapped due to a robust sanctions regime for non-compliance with international agreements on nuclear disarmament and grave human rights violations.

The nuclear rhetoric from Trump and the heated debate about the likelihood of a targeted military strike against North Korea stoked up by senior members of the administration — be it to scare China into compliance or not — has re-opened a long dormant debate about the potential for nuclear war and the impact (and feasibility) of forced regime change in Pyongyang. The policy approach to Kim Jong-un’s provocations, however, has been much more conventional than the fighting words might suggest. Over the past 12 months, with the support of the international community, including Russia and China, sanctions against DPRK were again significantly enhanced as part of what has been labeled a “maximum pressure” campaign. The focus of the Trump administration has been on sanctions increase and sanctions enforcement, holding others — especially China — more directly responsible for sanctions evasion, including through joint monitoring and a more direct calling out of violations.

Military Exercises and Allied Show of Force

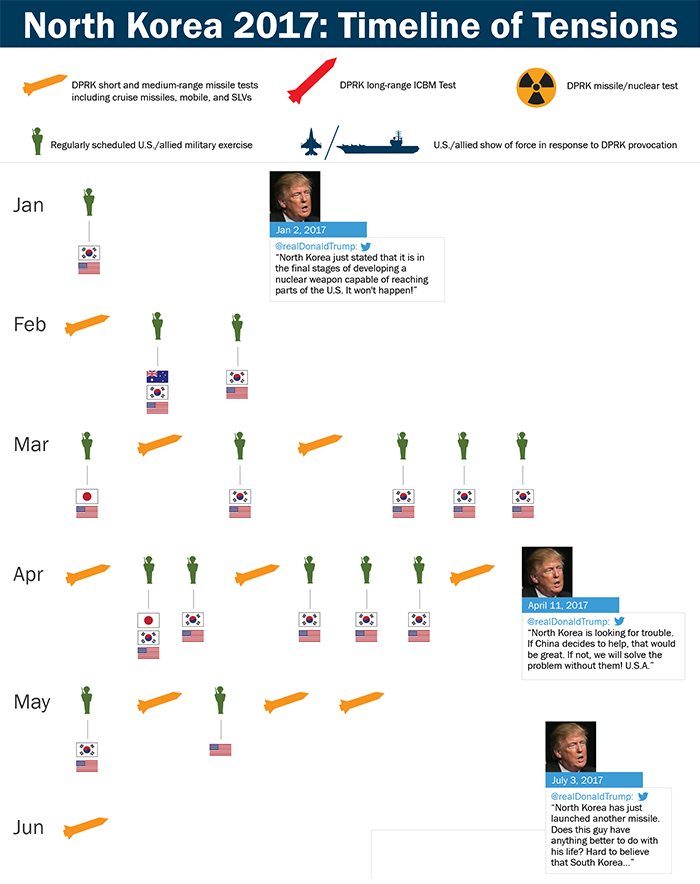

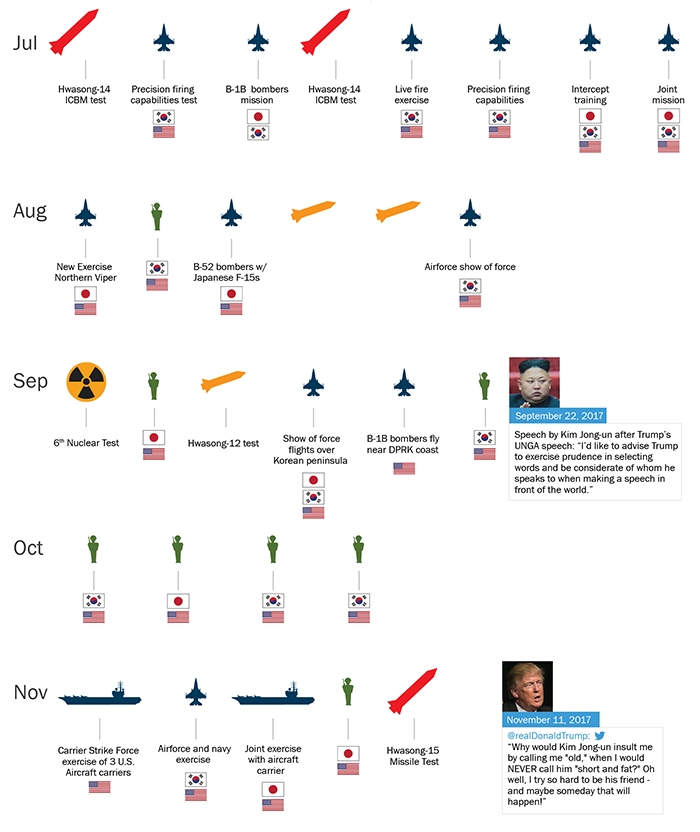

A look at the timeline of North Korean missile and nuclear tests and military exercises of the United States and its allies shows that the pressure remains high. Since Trump’s inauguration, there have been almost constant military exercises in the region. Most of them are longstanding annual or semi-annual exercises that have been a persistent feature of the U.S. military presence in Asia-Pacific and a constant nuisance to the Kim-regime.

But over the past 12 months, North Korean provocations have also generated targeted responses of the United States and its allies in the region as a clear show of force and indication of resolve and military readiness. Those responses did not come after each of the missile tests conducted by the North Korean regime. Only the successful intercontinental ballistic missile tests, which significantly raised the threat level for the United States, triggered a direct response. Importantly, and in contrast to some of Trump’s rhetoric, the activity was not a unilateral U.S. move but evolved around strengthening regional alliances and enhancing joint fighting capability with Japan and South Korea. Derogative comments by President Trump regarding perceived imbalances within the U.S. alliance system and constant quarrels over trade issues with both of these allies have not resulted in U.S. military retreat from the region. Quite the contrary.

This is not the first cycle of provocation on the Korean peninsula — there were arguably equally critical times in U.S.–DPRK relations in the 1990s or early 2000s, which were usually followed by a brokered diplomatic deal exchanging DPRK compliance with nuclear non-proliferation and safeguard mechanisms for economic aid and technical cooperation. And it will likely not be the last. At the one year mark of the Trump presidency, we are also witnessing the end of a cycle marked by diplomatic overtures between North and South Korea and de-escalation attempts through direct talks and re-opening of the military hotline.

North Korea has persistently called for an end of U.S. military exercises in its immediate vicinity, which Kim Jong-un claims threaten the security of North Korea. The re-scheduling of the annual Foal Eagle and Key Resolve exercises by the United States and South Korean military for the upcoming Olympics in Pyeongchang, are a sign of support of the South Korean effort for de-escalation and looking at the usual degree of activity mark an actual pause for at least a few weeks. It remains highly questionable, however, that the détente will last. The United States has a huge interest in an easing of tensions further into 2018. But it will not be easy.

This Time It’s Different

After its first year in office, the U.S. administration under the leadership of President Trump has provided two documents (National Defense Strategy and National Security Strategy) outlining the current strategic environment. China and Russia are singled out as the most important threats to U.S. interests and strategic rivals. On the other hand, both countries have a key role to play regarding security on the Korean peninsula.

In this confrontational environment, two factors make the current developments even more explosive than in the decades before. First, as indicated North Korea has demonstrated the availability of intercontinental ballistic missiles that put the continental United States within striking range and declared itself a nuclear power with no policy change to be expected. Second, even if the policy response has so far been comparatively firm and measured, the rhetoric employed by President Trump amplifies a bellicose environment and insecurity about U.S. security commitments among friends and foes alike. This makes military action and further provocation from North Korea more likely. Any action that undermines the actual or perceived strength of the alliance with Japan and South Korea can have a detrimental effect. Antagonizing rhetoric does not help ease nuclear tension, signaling resolve and enhanced cooperation with allies might.