Corridor Politics

On trade deals with Southern partners, Ursula von der Leyen is all superlatives these days. “The mother of all deals”, no less, was the EU Commission president’s shorthand for the recently concluded EU-India free trade agreement (FTA). An analogous pact with Mercosur countries received similarly exuberant praise from European leaders, as did the launch of the India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor (IMEC), a generational infrastructure project boosting EU-Asia trade.

The backdrop to this enthusiasm is vulnerability. The EU feels increasingly squeezed by Russian aggression, Chinese competition, and US volatility-turned-hostility. The bloc sees boosting ties with key partners in the “Global South” as a lifeline.

Connectivity corridors that structure freight trade flows and supply chains are central to this dynamic. In a competitive environment, they gain importance as a tool of structural influence, geopolitical leverage, and order-building. Increasingly, these corridors are understood as bundled infrastructure systems that encompass freight, energy pipelines, undersea cables, and telecommunications networks, and function as vectors of regional integration and development.

Much has been written on how China spent a decade implementing its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) while Europe remained largely inert. The EU remains far from building a global network on the scale of the BRI, but something has shifted. In just a few years, connectivity—driven primarily by Brussels’ Global Gateway—has moved to the center of European strategic debates. Securing a diversified, safe, and cost-efficient transport infrastructure across Eurasia has become a key lever in Europe’s broader de-risking agenda.

The Power of Options

Geopolitical shocks since 2020 have pushed diversification of trade routes and suppliers to the top of Europe’s agenda. The COVID-19 pandemic and Russia’s war against Ukraine exposed supply chain vulnerabilities and highlighted the strategic risks of transit dependence. Houthi attacks on shipping in the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden have again underscored the vulnerability along the Suez Canal/Red Sea corridor, the principal east-west trade artery.

Europe’s geopolitical vulnerability from its dependence on China for critical supplies, notably in technology and critical raw materials, has been well documented. The bloc’s reliance on the United States in defense, finance, fossil fuels, and technology drew less scrutiny until Washington’s recent policy swings highlighted the risks. The renewed tariff escalation under the second Trump administration has reinforced the need for diversification of value chains and exploration of new export markets. Even if the transatlantic alliance remains central to its security, Europe has strong incentives to hedge against policy discontinuity and economic risk.

Parallel to Europe’s messy gradual decoupling from Russian fossil fuels in the aftermath of the 2022 full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the bloc has had to reroute its Eurasian trade so that it bypasses Russia, thereby preventing the country from evading sanctions. A positive side effect of this shift is deeper integration of the Black Sea region, Central Asia, and India into European value chains. Diversified East-West trade routes that bypass Russia reduce Moscow’s transit rent and coercive leverage while offering alternatives to BRI-centered paths. That said, most corridors continue to rely heavily on Chinese trade volumes, infrastructure, and financing. Route diversification may fragment routes without fundamentally displacing Chinese influence, but it may still reshape the conditions under which that influence is exercised. A more diverse connectivity landscape reduces route monopolies and enhances negotiating leverage for transit and destination countries, even as China remains a central commercial actor. At the same time, Europe faces the broader challenge of ensuring EU connectivity efforts benefit from—rather than bypass—Chinese infrastructure investments.

While structural dependencies remain long-term challenges, diversifying supply chains and corridors helps mitigate exposure by reducing reliance on chokepoints and single suppliers. Diversification is also a matter of scale. Asian economies are set to grow twice or three times as quickly as the eurozone, and the EU expects cargo volumes between itself and India to more than double by 2032 under their new FTA. Accommodating such growth will require substantial investment in Europe-Asia connectivity infrastructure.

The Eurasian Corridor Network

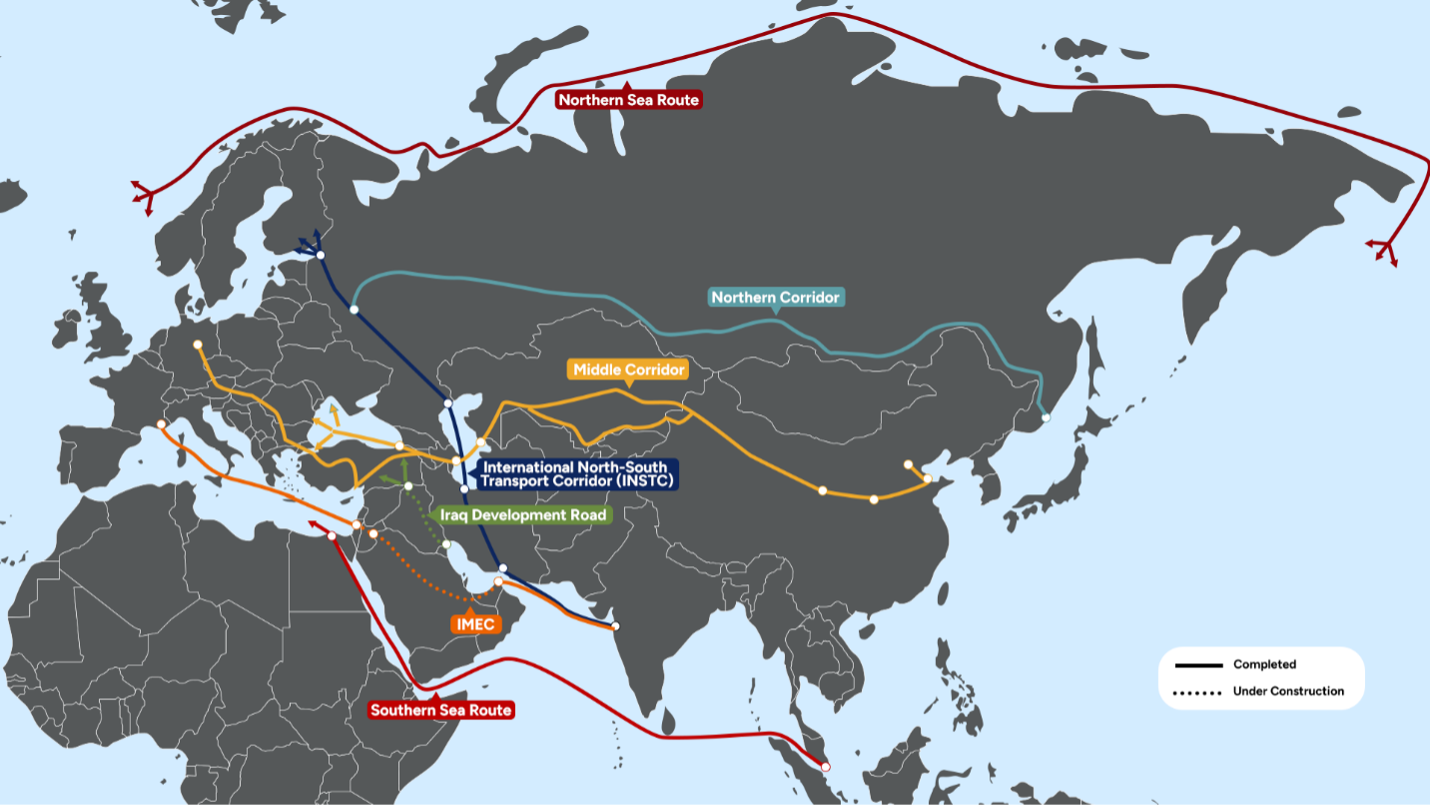

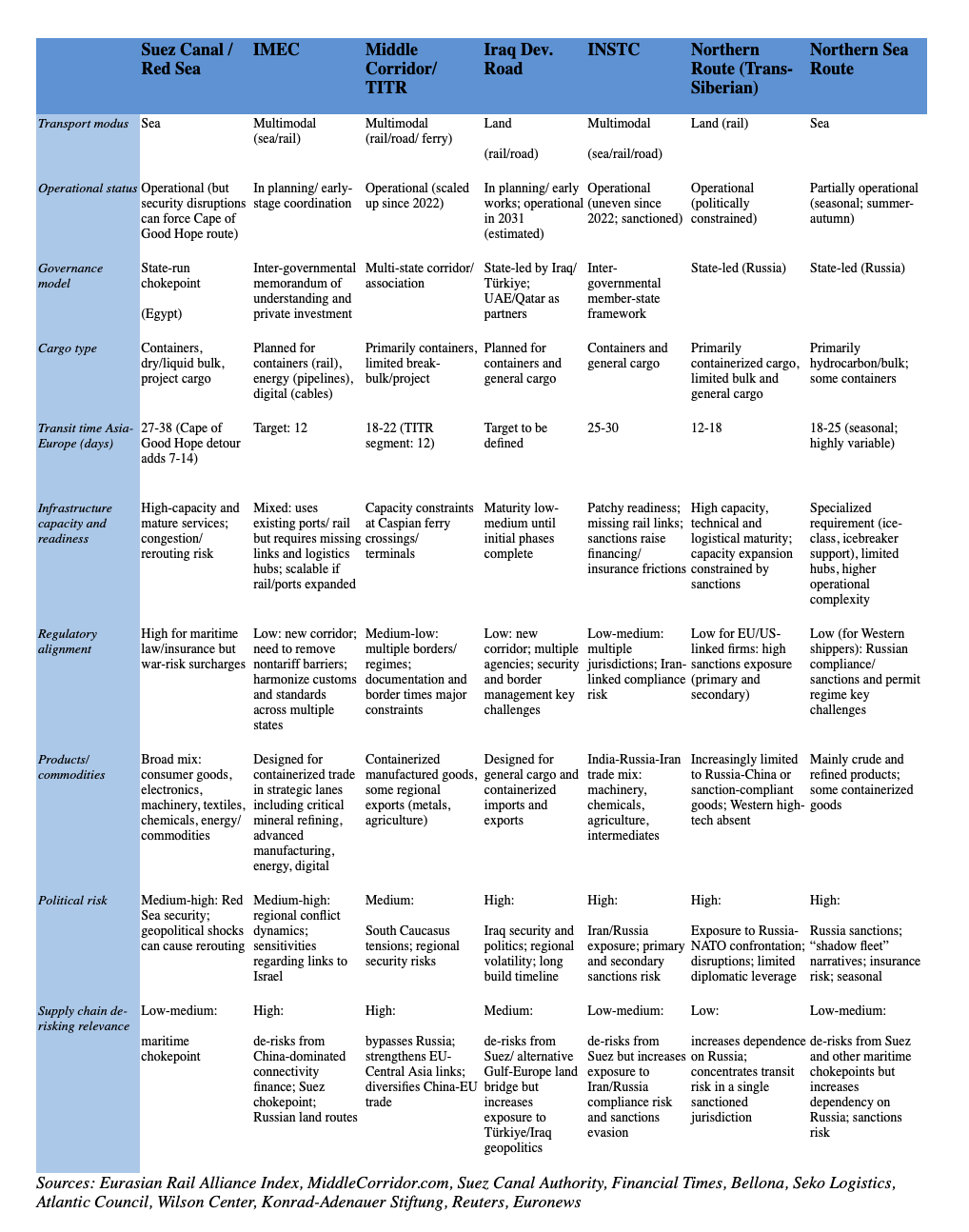

Europe’s Eurasian connectivity options can be broadly grouped into three route families—Northern, Central, and Southern (see Figure 1)—each with distinct strengths and constraints. The interaction among multiple complementary routes ultimately shapes Europe’s geopolitical and geo-economic room for maneuver (see Table 1 on p. 4).

Figure 1: Europe-Asia Corridors

Credit: GMF

Northern Routes: Bypassing Russia

The Northern Corridor, also known as the Trans-Siberian or China-Europe railway, was the dominant land route before 2022, carrying up to 86% of China-EU rail freight through Russia and Belarus. Russia’s invasion transformed it from a logistics backbone into a political and commercial liability. By 2023, China-EU freight volumes had fallen by roughly half, eroding Russia’s transit leverage with Europe.

Europe’s avoidance of the corridor has encouraged Moscow to accelerate alternatives less exposed to Western sanctions. The International North-South Transport Corridor (INSTC), previously marginal in volume terms, partially serves this purpose by linking Russia to Iran, the Caucasus, the Persian Gulf, and India through a multimodal north-south route. INSTC could allow Moscow to monetize its geography even as westward connectivity remains structurally constrained.

The Northern Sea Route (NSR) along Russia’s Arctic coast, the shortest maritime route between Europe and the Asia-Pacific, but usable for only 3-5 months per year, currently transports mainly Russian commodities to China. While it could marginally reduce exposure to Suez disruptions, Europe’s reliance on the Russian-controlled NSR would deepen dependence on Moscow. A durable end to the Ukraine war, however, could revive Arctic investment and recast the NSR’s political and economic viability.

Table 1: Europe-Asia Connectivity Corridors

Central Routes: Gateway to Central Asia

The term “Middle Corridor” is commonly used as the overarching concept for Europe-Asia connectivity via Central Asia, the Caspian Sea, the Caucasus, and Türkiye. Promoted as a geopolitically safer alternative to Russian land routes and the Suez Canal, the corridor has gained renewed relevance as a “third vector” since the war in Ukraine upgraded its strategic significance and that of its principal institutional branch, the Trans-Caspian International Transport Route (TITR).

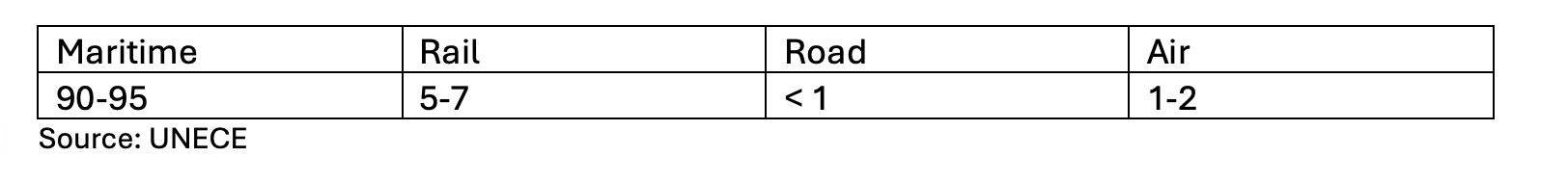

The Middle Corridor carried less than 1% of cargo between China and Europe before 2022. As trade via the Northern Corridor collapsed, Middle Corridor traffic surged, growing 70% in 2023 and 90% in 2024. Pressure to bypass Russia has boosted multilateral efforts to address infrastructure and regulatory bottlenecks. The volume of trade on the Middle Corridor, however, remains small compared to that carried by maritime shipping(see Table 2).

As the only operative China-Europe land route without major geopolitical roadblocks, the Middle Corridor is drawing interest and investment. Yet it faces significant constraints: outdated infrastructure, regulatory fragmentation, Caspian Sea governance issues, risk of sanctions evasion and cargo deviation, and lingering tensions between Armenia and Azerbaijan. The corridor is not formally a BRI route, but parts of it are linked to the initiative, and expansion could deepen European dependence on Chinese suppliers. For Europe, the corridor’s main value, beyond route diversification, lies in integrating Central Asia into European value chains.

Table 2: Modal share of EU-Asia freight (in %, 2020-2024)

Southern Routes: Suez Stays, IMEC Reckons

The Southern sea route via the Suez Canal and the Strait of Hormuz remains the fastest and cheapest Asia-Europe link. Prior to recent disruptions, the canal carried an estimated 15% of global trade, and up to a quarter of global container traffic. Recent Houthi attacks temporarily reduced traffic but did not alter the route’s centrality. The Suez route is an integral part of the BRI, and Beijing’s investments and port deals in and around the canal have raised concerns of Chinese dominance of the Suez Canal Economic Zone. Despite its vulnerability, the waterway will remain indispensable as long as shipping remains the most efficient mode for large-scale container transport and no alternative maritime route can operate on the same scale (the NSR is politically and climatically constrained; a detour around the Cape of Good Hope adds significant time and cost).

IMEC, established by India, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, the United States, the EU, France, Italy, and Germany in 2023, aims to complement maritime trade by providing a multimodal corridor that bypasses China and Russia while positioning Gulf states as energy, technology and logistics hubs. The project is driven in part by China–US strategic competition, reflecting broader efforts to diversify supply chains, reduce strategic dependencies, and shape connectivity standards beyond China-led frameworks. The EU–India FTA further reinforces IMEC’s economic logic by deepening market integration, regulatory convergence, and long-term trade growth between Europe and India.

IMEC has gained new momentum following a two-year freeze due to the Gaza war. But despite this and the establishment of the first governance structures, the corridor’s trajectory remains contingent on regional stability amid renewed Middle East tensions, long implementation timelines, and uncertain financing. Talk of linking IMEC to Gaza reconstruction has also gained traction. Following backlash from sidelined countries, IMEC is increasingly framed as a flexible connectivity network rather than a single corridor.

The project’s strategic relevance lies less in immediate throughput than in its function as an umbrella framework that boosts regional integration and development and that aligns and accelerates preexisting transport, energy, and digital projects (e.g., the Blue Raman undersea cable). IMEC is meant to serve two goals: diversifying routes and suppliers by complementing BRI options, and integrating India into European supply chains. Occasionally hyped as a solution to multiple geopolitical challenges, IMEC’s trajectory will remain contingent and incremental. Its de-risking potential warrants cautious optimism, not exuberance.

IMEC’s launch and Europe’s need to strengthen connectivity without Russia have also injected energy into complementary regional efforts. Among them is the Three Seas Initiative, a project connecting 12 eastern-flank EU member states from the Baltic to the Adriatic and Black seas through enhanced road, rail, port, and gas infrastructure. The Iraq Development Road, a prospective Gulf-to-Europe land bridge promoted by Türkiye and the Gulf states, is another effort that could complement or compete with IMEC.

Europe’s Corridor Politics

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine triggered a profound reorientation of European connectivity thinking toward emerging economies in the “Global South”. The EU’s main infrastructure scheme, Global Gateway, launched in 2021 with a €300 billion mobilization target for the period through 2027. It was initially criticized for using repackaged existing funds but has surpassed the target and now aims for €400 billion. The initiative has also expanded its geographical focus beyond Africa to Asia and Latin America. Despite limits in scope and implementation speed, the Global Gateway is increasingly acknowledged as an incremental but meaningful contribution to global infrastructure competition, leveraging rule-based, sustainability-oriented projects while serving Europe’s geopolitical, industrial, and development objectives.

Trust and confidence in Global Gateway’s value proposition varies across Asia. There is frequent skepticism about the EU’s delivery capacity compared to that of the bloc’s competitors. Interviews conducted for this article revealed that a frequent critique is the initiative’s heavy, fragmented bureaucracy and slow, conservative due diligence processes that cannot compete with the fast, transformative infrastructure funding under the BRI. Brussels typically argues thatthe scheme’s added value lies precisely in strengthening EU normative and strategic influence rather than in speed and funding volumes. However, bloc officials also increasingly acknowledge the competitiveness challenge and point to an “ongoing thought process” to find the Global Gateway’s genuine niche.

Investments made through the initiative in the Middle Corridor and Central Asia have increased, with flagship projects for Trans-Caspian transport, critical raw materials, regional water and energy integration, logistics integration, and trade diversification. Large EU investments in infrastructure have led to growing intra-regional trade in Central Asia. At the same time, EU officials acknowledge that the bloc’s often ambiguous reluctance to engage with important but politically difficult partners, such as Türkiye or Georgia, creates additional constraints.

Unlike TITR, IMEC is not an institutionalized Global Gateway program with dedicated financing, but it aligns with Global Gateway goals. France, Greece, and Italy, which seek to position their ports as European gateways, also promote it heavily, as do EU institutions. Notably, IMEC offers convergence opportunities with US connectivity efforts, including those by the newly relaunched International Development Finance Corporation, which is presented as a competitive challenger to BRI infrastructure financing.

Not A Panacea

In an era of unstable multipolarity, diversification is not alliance betrayal but a pragmatic insurance policy. Europe has strong incentives to pursue multi-vector strategies and structural hedging, and connectivity investment is central to EU competitiveness and industrial policy. However, the de-risking potential of route and supplier diversification has its limits.

Corridor investments cannot rebalance deeper structural dependencies in industry, finance, or security. They constitute a complementary resilience layer that mitigates exposure to single points of failure when dependencies cannot be eliminated in the short term. Corridor networks are generational projects. All routes remain vulnerable to disruption, soft obstacles, political contestation, and fiscal constraints.

Land corridors will not substitute for maritime trade at scale. Their value lies in providing a backup for time-sensitive, high-value, and disruption-prone segments. Corridor diversification will not transform global trade, but small shifts at the margins can produce outsized geopolitical benefits.

Even with all these constraints, Europe’s bet on free trade and connectivity corridors marks a long-delayed decision to use trade, its core strength and comparative advantage, as its primary geopolitical asset. Investing in new partnerships with high-growth economies, and in the corridors that give those ties material form, could help supply the economic foundation for the geopolitical coming-of-age that Europe-watchers have long called for.

The author would like to thank Peter Chase, Eamon Drumm, Sharinee Jagtiani, Gabriel Mitchell, Kadri Tastan, and Özgür Ünlühisarcıklı for their useful comments on a draft of this text, and Subigya Basnet for the graphic.

The views expressed herein are those solely of the author(s). GMF as an institution does not take positions.