How Gen Z Can Give a New Impetus to the Weimar Triangle

Summary Points

Thirty years after the launch of the “Weimar triangle” by France, Germany, and Poland, Europe has changed. For Gen Z (those born after 1996), the world and the Weimar relationship look very different. The Transatlantic Trends 2021 survey reveals that, in contrast to their older compatriots, they favor less U.S. involvement in Europe, have a more positive perception of China, and are less likely to see their respective countries as reliable partners.

The degree of convergence among this younger generation across the three Weimar countries is so striking that the format might be ready for a Gen Z form of cooperation—and even serve as a European pivot in transatlantic cooperation, as their priorities and opinions converge with the views of young respondents in the United States.

To make the Weimar triangle format fit for the next 30 years, France, Germany, and Poland can take the following measures: making Weimar cooperation a visible political priority again and increasing their efforts in public diplomacy, enhancing civic education about future challenges in a changing world order, and ensuring that the policymakers of tomorrow develop China expertise.

Rebalancing Power in Europe

Launched in 1991 as an informal format of cooperation between France, Germany, and Poland, the Weimar triangle started with high aspirations: including France in the process of reconciliation between Germany and Poland based on the French-German spirit of reconciliation, strengthening dialogue and cooperation among the three countries, and supporting Poland in its process of integration into NATO and the European Union. Thirty years later, the political landscape in Europe has changed: Poland is a member state of the EU and NATO, and the reconciliation process between Germany and Poland has made considerable progress. However, while cooperation among the Weimar countries was considerably more en vogue a few years ago, the natural reflex for coordination among them seems to have slowed down. Even more so, recent political events show cracks in the Weimar relations, be it because of French initiatives dismissed as unilateralism, the German-Russian pipeline project North Stream II seen as a threat to European security, or Polish domestic politics harvesting harsh criticism by the partners. Similarly, the debates on European strategic autonomy (as the French call it) or sovereignty (the term preferred by the Germans and Polish) underline that Weimar cooperation is not a natural given but requires a process of diplomatic work and compromise.

Despite these controversies, there is little doubt that the Weimar countries can play a key role in mitigating the challenges the EU is facing internally and externally, as they bring together different political and strategic cultures and can therefore help strike a balance between different interests within Europe. Following the commitment of the Biden administration to work closely with European allies on shared challenges, the Weimar countries could, thanks to their diversity in terms of strategic priorities and ties with other European countries, become a key interlocutor to the administration and thereby complement EU-based formats of cooperation. In this context, Weimar cooperation might function as a catalyst for broader European action and give a new impetus to cooperation within the EU institutions. This brief focuses on youth opinion in the Weimar countries and the United States, arguing that it is time for a revitalization of the format, including by connecting it to the United States.

The Weimar format is particularly relevant in light of the findings of Transatlantic Trends 2021. Overall, slightly more than 70% of all respondents in the three countries (71% in Germany, 72% in France, 75% in Poland) see Germany as the most influential country in Europe, followed distantly by the United Kingdom (17%) and France (7%). Except for young Germans, who perfectly align with their older compatriots and see Germany by far as the most influential actor (73%), respondents of Gen Z in Poland and France do not have such a perception. While 17% of respondents in France consider their own country the most influential in Europe, the share is significantly higher among Gen Z respondents, as more than one-third of them (36%) describe France as the most influential. As the political memory of this generation dates back to the election of Presidential Emmanuel Macron and his strongly pro-European campaign and profile, one could even describe them as “Generation Macron.” This comparatively higher perception of French influence in Europe comes at the expense of German influence, which lies significantly below the national average (43% vs. 72%). It might also lead to an increasing quest for French co-leadership in European affairs, hence rendering French-German cooperation and the Weimar triangle suitable formats to live up to this aspiration while considering the diversity of views in Europe. Cooperation on the same level might also appeal to young Polish respondents: similar to their older compatriots, they see Germany as the most influential country, albeit to a lower extent (60% vs. 75% on average), while they perceive the influence of France and Poland to be at almost the same level (5% and 4% respectively). Consequently, teaming up with France in the Weimar format could become an interesting option again to increase the respective weight in European affairs while relying on Germany—often occupying a middle ground between the strongly divergent Polish and French positions—to bridge the most important gaps.

Gen Z Americans also have a more distributed view of European power. In the eyes of the youngest American respondents, the influence of Germany and France is almost at the same level (15% and 11% respectively), so that, in the long term, the road to Europe for the United States may lead through at least Paris and Berlin. Given that the power perceptions of France and Germany are almost at the same level, the Biden administration should adopt a balanced approach that takes both partners in Europe equally seriously instead of focusing exclusively on Berlin.

Transatlantic Trends 2021

Transatlantic Trends 2021 is a comprehensive study on public opinion by the German Marshall Fund of the United States and the Bertelsmann Foundation, conducted in 11 countries—Canada, the United States, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Poland, Spain, Sweden, Turkey, and the United Kingdom—between late March and mid-April 2021. The data was collected from online access panels with self-completion, and then weighted to match population totals for the following factors: gender, age, and region (according to local standards) in all countries, as well as income (in Canada, the United States, Germany, Italy, Poland, and Spain), and occupation (in France and the United Kingdom). In each of the countries, the sample consisted of 1,000 persons aged 18 and above.

Cracks in Perceived Reliability

While a 3+1 format of cooperation between the Weimar countries and the United States might appear a smart natural choice in light of the current geopolitical setup and the perceptions of influence in Europe, the Transatlantic Trends data show that cooperation among the three countries or between them and the United States cannot be taken for granted.

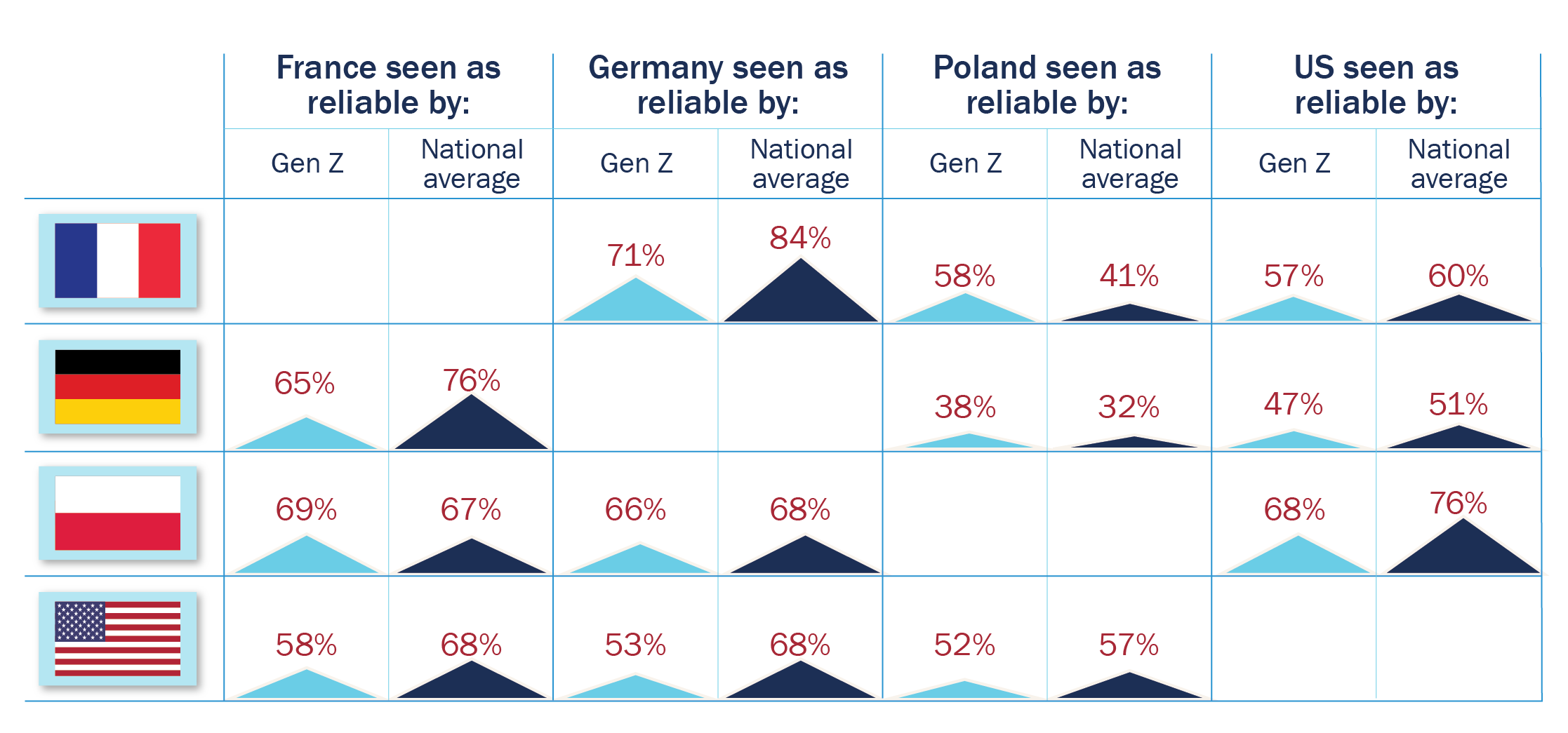

Partnerships and reliability are perceived very differently by respondents younger than 25. Compared to their older compatriots, Gen Z respondents in the Weimar countries and the United States are less likely to perceive the other countries covered by the survey as reliable partners. In the context of Weimar, this is particularly striking for the French-German relationship, with Gen Z respondents’ perception of the respective other country as reliable more than 10 percentage points below the national average (71% compared to 84% for German reliability as perceived by the French, 65% compared to 76% for French reliability as perceived by the Germans). Although these numbers are still high and among the highest in the respective national contexts, it is a point of concern that trust, even among established partners, is significantly lower among younger people.

In fact, working within the Weimar format could be a promising solution to revitalize French-German cooperation and to broaden its scope for a more inclusive European approach: young French respondents are much more likely to perceive Poland as a reliable partner than their older compatriots (58% compared to 41%), and young Polish respondents equally consider France to be highly reliable (69% compared to the 67% national average). This high level of mutual trust in the young French-Polish generation is thus a hopeful sign for a new impetus for Weimar cooperation. Although trust among young Weimar respondents is lower than among their older compatriots, the absolute level of trust is still relatively high, and, most importantly, mutual.

This reciprocity in the perception of reliability can also be observed when it comes to the U.S.-Weimar relationship in the eyes of young respondents. Overall, the young respondents in the Weimar countries align with the respective national averages on this question, with 68% of young Poles, 57% of young French, and 47% of young Germans considering the United States as reliable. Young American respondents perceive the reliability of Germany, France, and Poland to be at nearly the same level as their European cohorts. However, the perceptions held by young Americans on the reliability of European partners lie significantly below the national averages for Germany (-15 points) and France (-10 points), and to a lower extent for Poland (-5 points). In other words: around half of the young Americans see the Europeans as reliable partners—which means that half of them do not. Consequently, enhancing trust among officials and citizens of the Weimar countries through exchanges on all levels is a must to make the format fit for the future.

When imagining the future of Weimar cooperation and U.S.-Weimar cooperation, one should try to see the world order and transatlantic relations through the lens and with the political memory of Gen Z: born between 1996 and 2003, they can barely relate to smooth examples of European or U.S.-Weimar cooperation. With the political memory of Gen Z marked by multiple crises—the euro crisis and financial instability in Europe, the challenge of coordinating migration policy, debates on NATO’s “brain death,” and a confrontational discourse by President Donald Trump on Europe—the cracks in perceived reliability are barely surprising. Nonetheless, this should be a wake-up call for politicians that good examples on the added value of the Weimar format and U.S.-Weimar cooperation are now needed more than ever—not only for the sake of maintaining historic ties, but to address shared challenges together.

Skepticism Towards NATO: Time to Adapt to New Security Challenges

The lack of collective memory within Gen Z can also explain NATO’s standing with it. Young respondents see the alliance as less important for their country’s security than their older compatriots do; however, their perception of security challenges is very similar, which shows that the Weimar countries could play a key role in redefining the scope of action for NATO.

In the United States, only half of respondents under 25 believe that the alliance is significant in ensuring U.S. security. This stands in stark contrast to the three-quarters of respondents from 25 to 45 years old who consider it to be important for the security of their country. Given that the United States is traditionally perceived as the backbone of NATO, this result is striking. Importantly, the older generations in the country were the only ones in the alliance to experience the application of NATO’s cornerstone Article V first-hand after the 9/11 attacks. Hence, respondents over the age of 55 see terrorism as the main security threat to this day. Meanwhile, Americans under 25 years of age, living in an era characterized by emerging threats, consider pandemics (27%) and climate change (23%) to be much more relevant than conventional security risks. Additionally, Gen Z came of age under the presidency of Donald Trump, marked by skepticism towards NATO, as he dismissed it as obsolete, decreased the number of U.S. troops in Europe, and threatened to withdraw from the alliance.

Hence, it is not surprising that young Americans do not think that the United States should be greatly involved in the security of Europe, with only 14% of those under the age of 25 agreeing with such a notion. Furthermore, only 54% believe that the United States should be generally involved in European security—24% less than the perception of the older generation. Again, the generational gap is evident, as the older cohort has personally witnessed U.S. involvement in Europe in the Cold War. In addition, 10% of respondents under 25 believe that the United States should not be involved in European security at all, while 20% indicate that they simply do not know enough about the subject. These figures beg the question of whether adequate effort is made in the United States to raise awareness and provide education on U.S. military and security engagements around the world. Furthermore, it is essential to explore whether the young generation agrees with such deployments and how their support or lack thereof could affect the ability of the United States to remain a superpower in the future. In the long term, the key challenge for the Weimar countries will be to develop a joint approach to redesigning U.S. engagement with and in Europe.

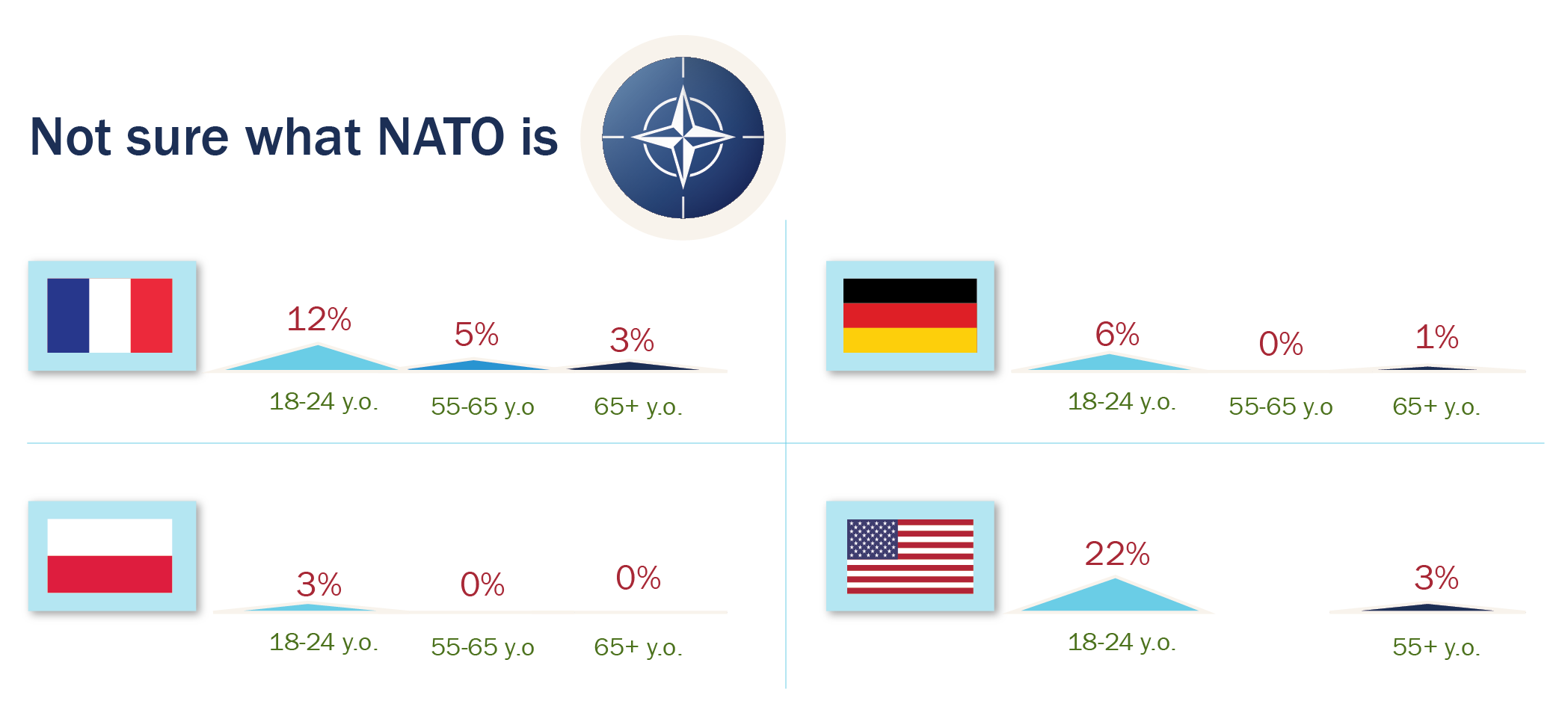

Similar to “Generation Trump,” Transatlantic Trends 2021 illustrates that hesitation toward NATO is shared in France: only 52% of respondents under 25 years of age think that NATO is important for France’s security. Yet, it is important to note that the number is not significantly higher in the older generations and differs by only 5%. Given that France’s strategic culture traditionally puts emphasis on European strategic autonomy, a narrative often taken up by President Macron, while being comparatively skeptical about NATO, this is not highly surprising. However, more worryingly, 12% of Gen Z in France do not know what NATO is—a number significantly higher than that in other Weimar countries: 6% in Germany and only 3% in Poland. Hence, the need for education on the alliance is the greatest in France, but necessary in all Weimar countries.

However, 53% of those under 25 in France believe that the United States should be involved in European security, which is higher than the older generation, with only 45% in the under 55 age group believing the same. Yet, the question emerges, whether U.S. involvement is seen as a positive or negative illustration of the lack of European capabilities, developed autonomously, as often emphasized by the Élysée palace. Overall, France exhibits the lowest numbers among the Weimar countries, with 60% of German respondents under the age of 25 believing that NATO is important for their country’s security. However, once again, there is a decline of such belief compared to the older generation—a tendency shared among all Weimar countries.

On the other hand, 70% of German youth believe that the United States should generally be involved in European security, a number in line with the older generation and which could make the general political push to re-ignite U.S.-German relations possible in the future. Germany and Poland could thus try to find common ground with France for cooperation between Weimar, or Europe, and the United States.

While the trend of decreasing faith in and support for allied security is shared among Gen Z in Poland, young Poles exhibit higher confidence in NATO and the United States than their French and German counterparts. An overwhelming 80% claim that NATO is important for Poland’s security. Yet, this number is lower than the perception of the older generation, where NATO enjoys almost total support (94%). Such belief can be explained by the fact that older generations lived under Soviet influence, and thus can contrast this experience with the later period as a NATO member. Importantly, for people in Central Eastern Europe, the alliance is often associated with their freedom and the benefits of membership are experienced first-hand to this day. With NATO deployments on Polish soil, allied support and guarantee of security feel as pertinent as ever. Living in a region benefiting from the presence of allied forces can also explain the perception of NATO’s high importance among the Polish Gen Z. Additionally, while those under 25 did not live under the communist regime, their collective memory is much broader than that of their peers France or Germany, with the youth hearing stories from their parents and grandparents, and political history being an extensive aspect of each pupil’s education.

Notably, 67% of Polish respondents under the age of 25 believe that the United States should be involved in the security of Europe, and interestingly the number is even greater than that of the older generation, where only 48% feel the same. Two factors can account for such discrepancies. First, experiencing an even greater U.S. involvement in the 20th century, the older generation is right to believe that the United States has decreased its presence in Europe, as the Soviet threat disappeared and as U.S. policy focus shifted to the Indo-Pacific. Second, from the youth perspective, the presence of the United States can also be felt in different areas, such as the cultural domain where its influence is extensive, and hence these perceptions of influence in various areas might be intertwined. In other words, the opinion of the Polish Gen Z can also be a product of Washington’s public diplomacy and soft-power influence among the European youth. Therefore, while the U.S-Polish bond might be the strongest among those between the countries examined, all still exhibit a decline in their perception of the importance of NATO and U.S. involvement in the security of Europe.

However, rather than seeing this as an issue, policymakers could see such attitudes as an opportunity to capture the attention of the Weimar and the future generation of U.S. policymakers. Gen Z respondents in all countries agree that the most important security challenges to their countries are pandemics and climate change. Hence, these areas present a window of opportunity for future U.S.-Weimar cooperation in security, and organizations like NATO should expand their agenda to include these security threats—in other words, they should develop a “Gen Z” security policy, meant to address the post-2021 challenges. The Transatlantic Trends findings show that when it comes to security, people tend to place emphasis on the issues that they get to live through in their lifetimes. Therefore, acknowledging that and trying to keep up with the issues of today will be essential to plan for the policies of tomorrow.

United in Diversity on China?

When it comes to perceptions on China, Gen Z in Weimar countries and in the United States also diverge significantly from older generations, and their views are characterized by a higher degree of diversity than their perceptions on other questions. However, this could be a significant asset for designing a Weimar approach to China.

Overall, roughly one-third of respondents aged below 25 in the Weimar countries hold a positive view of China’s influence in global affairs. Gen Z in the United States aligns here with 35% having a positive view, while those aged above 55 years across older generations in all four countries tend to be much more critical of Chinese influence. While 55% of Polish Baby Boomers have an overall negative image of China, attitudes of this age group in France, Germany, and the United States diverge even further from those of Gen Z: More than 75% have a negative image of Chinese influence.

The difference in perception between the younger and older generations is particularly striking concerning bilateral relations: Whereas 52% of Polish and 42% of German youth tend to view China as a partner, French and American Gen Z is more skeptical, and only 28% and 25%, respectively, consider China to be a partner to their countries. Albeit the Polish Gen Z and Boomers align and 27% of them refer to China as a rival, there is a 30% difference between the youngest and the oldest age groups in France, Germany, and the United States when assessing their own country’s relation to China, as 56% of Germans aged 55 or older, 70% of French, and 89% of Americans see China as a rival. While China’s growing influence has been subject to public debate in these countries, this has not really been the case in Poland mainly due to lack of interest.

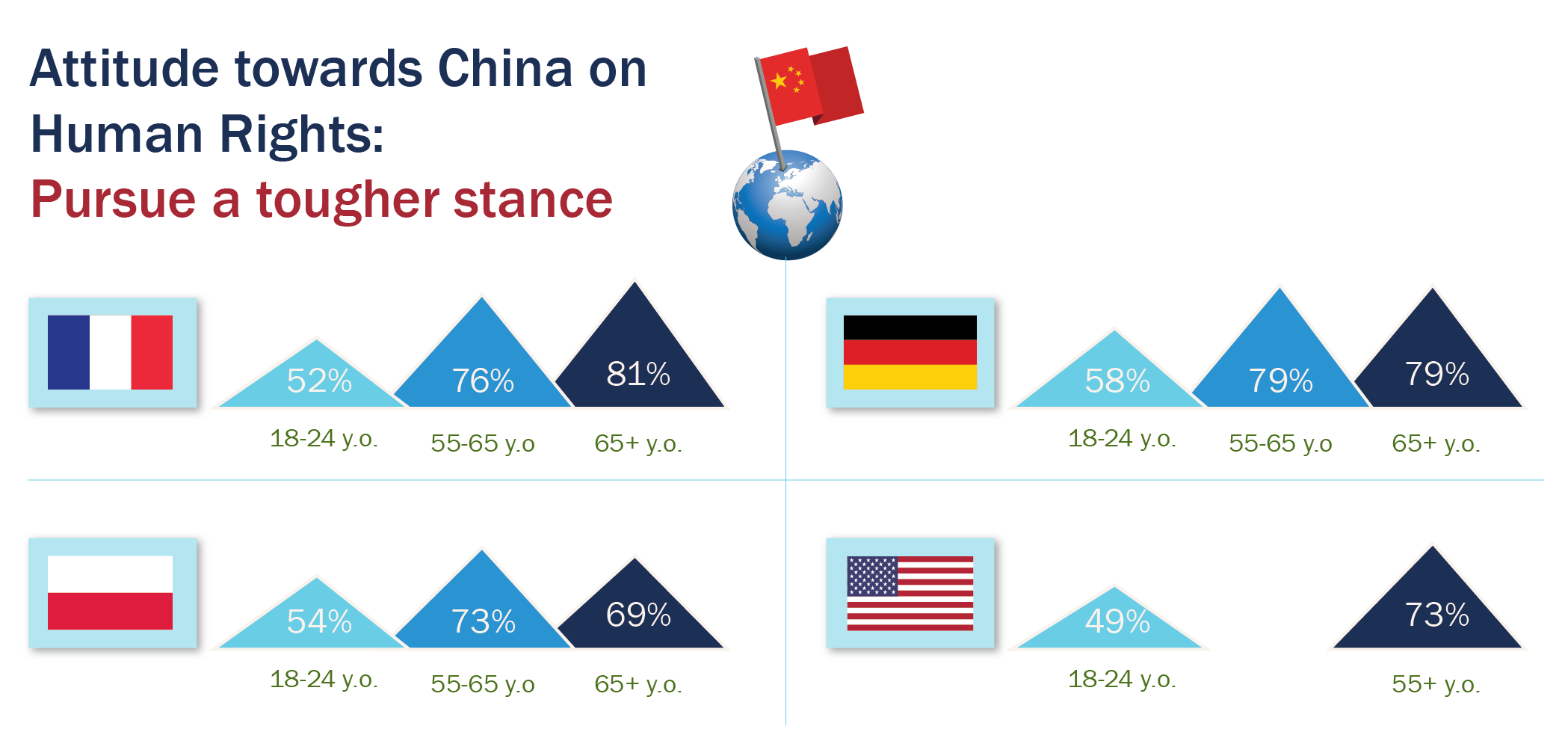

Asked about how they would approach climate change with China, Weimar and U.S. Gen Z are again very aligned. Although the majority is in favor of being tougher with China, this stance is less pronounced than in older generations. Similarly, the majority across all generations favors a tougher stance on human rights vis-á-vis China, yet there is a significant difference between the severity of Gen Z and Boomer opinion. While about four in five Boomers hold this view, only every other member of Gen Z from the Weimar countries and the United States support being tougher with China. This difference of about 20% persists across all four countries.

Notwithstanding that youth in Poland, France, Germany, and the United States in comparison to older generations tend to favor softer approaches to China on issues ranging from technological innovation, to trade and territorial expansion, they are not overly enthusiastic about China either. No more than 1 in 10 of those aged below 25 have a very positive image of the country. This begs the question whether recent Chinese public-diplomacy efforts have met their goals or whether Gen Z is not as politicized as older generations as far as attitudes on China are concerned.

The role of education and research cooperation may play a significant role in influencing youth perspective on China. The launch of Confucius Institutes, initially compared to the British Council and the Goethe Institutes, marked a turning point in Chinese public diplomacy in the early 2000s. By offering publicly available classes teaching language and other cultural activities, these state-affiliated institutes sought to project a positive image of China to the rest of the world. Confucius Institutes are typically affiliated with a Chinese university and directly located at a local host university. Supervised by Hanban, an agency linked to the Chinese Ministry of Education, teachers are reportedly instructed to avoid discussing topics such as the issue of Taiwan’s statehood or Tiananmen square. In 2018, there were 19 Confucius Institutes in Germany, 17 in France, and six in Poland. Amid legitimate concerns and mounting criticism about threats to academic freedom and censorship, several universities in Germany, France, and the United States (among others) have since ended their cooperation with Confucius Institutes. Chinese public diplomacy in Poland is typically less controversial than within German and French civil societies, which may explain Polish Gen Z attitudes.

Economic prospects increased the appeal of studying Chinese language and culture for Gen Z in Weimar countries. Before the spread of the pandemic, for example, France was the European country with the highest number of young people studying in China. Recently established business-oriented organizations, such as the France-China Foundation or the Berlin-based China Bridge, along with larger networks of elites are seeking to establish young leadership programs to strengthen ties that in turn might further impact Gen Z attitudes on China.

As is the case when it comes to threat perceptions and views on security policy, youth in the Weimar countries as well as in the United States do not have collective memories of autocratic regimes. Further, older generations may remember China under Deng Xiaoping, who introduced a policy of “reform and opening” and pushed for greater international engagement, and now compare it with Xi Jinping’s tightened grip over the country. Gen Z, however, lacks any point of reference as Xi assumed power in their teen years.

While efforts to foster favorable public opinion through media cooperation and a more assertive presence on social media by Chinese officials have increased over the past few years in general, their influence on youth perceptions remains limited: Gen Z is not their main target group. Yet, this younger generation may also hold more favorable views of China, in comparison to others, as a backlash against Donald Trump’s aggressive stance on China, ranging from racist slurs amidst the spread of the pandemic to his proposed ban of the popular social media platform TikTok.

The diverging views of youth and Gen Z in the Weimar countries, especially in France and Germany but also in Poland, and in the United States, are not a result of Chinese public diplomacy alone. While the effectiveness of Chinese influence has dwindled in general, the Transatlantic Trends 2021 survey demonstrates that there is a clear perception gap between the attitudes of Gen Z and those of older generations. If the Weimar countries, together with the United States, want to successfully implement a joint transatlantic agenda, they need to bring youth on board –only then will they be able to develop sustainable policies fit to tackle future challenges. This includes to take their current opinions on China seriously and to reflect on their implications for China’s role in the international order and their reaction to it. On the other hand, future policymakers should automatically mainstream China in their strategic thinking; hence the need for significantly increasing China expertise across Weimar countries.

Showing that Weimar Matters

While the Transatlantic Trends 2021 survey shows that the Weimar countries diverge on many issues, this should not be a reason to abandon the format and to rely on unilateral or bilateral initiatives on topics where two partners find common ground. Likewise, designing the future of the transatlantic relationship should not be left to the United States and Germany alone, although the latter can undoubtedly be considered the privileged partner of the Biden administration in Europe. In fact, it is their diversity that makes the Weimar countries such a promising trio for advancing cooperation within Europe and across the Atlantic. With their different political cultures, strategic priorities, and strengths, they represent distinct positions within the EU but still manage to negotiate and develop effective solutions.

The Weimar countries can thus play a key role in advancing European and transatlantic cooperation by once again becoming a force of productive suggestions and initiatives, which could then lead to concrete actions in the EU, in the wider context of European coordination, and in the transatlantic relationship. That is why it is crucial to make Weimar work again—for current and future challenges. Yet, this also needs a generation of future policymakers and experts that are convinced of the added value of this format. Thirty years after the formation of the Weimar triangle, four steps should be prioritized to achieve this objective.

France, Germany, and Poland Have to Make Weimar a Priority Again

This work starts at home and in their own structures. Weimar cooperation must be consistently mainstreamed in national foreign policy and European policy, leading to a “reflex” for Weimar cooperation. Concretely, this would imply a strong public commitment to the Weimar format and more visibility for joint initiatives and policies at the highest political levels, such as regular and public ministerial meetings and high-level working groups. By publicly stepping up their efforts to advance European cooperation and transatlantic relations through Weimar, current leaders thus set a good example that this format can, despite all challenges, lead to productive outcomes and hence benefit larger objectives.

In this context, political leaders should not shy away from explicitly mentioning the challenges of finding common ground due to the different approaches, priorities, and cultures of the Weimar countries, as these divergences and differences can make their cooperation inclusive and thereby sustainable. In this context, political leaders should equally underline that Weimar cooperation is not about making France, Germany, and Poland more of the same, and to abandon identities and priorities, but that it is about finding consensus and unity in diversity. The 30th anniversary of the Weimar triangle is a perfect occasion to give a new impetus to Weimar by publicly celebrating achievements and underlining the added value of this format, while naming challenges to tackle jointly in the future. In this sense, a new Weimar declaration by the end of 2021, after the formation of a German government and before the French takeover of the rotating presidency of the Council of the EU, would be a perfect belated birthday present. Besides this high-level political impetus for Weimar cooperation, France, Germany, and Poland should see this format as a “go-to” and develop a “Weimar political culture” within their institutions and national bureaucracies. Long-term exchanges (for up to a year) among career officials in different ministries should be increased—and Weimar cooperation should be systematically included in the training of young diplomats and other officials. Finally, regular parliamentary exchanges should be established between the parliaments of the Weimar countries.

Increasing Efforts in Public Diplomacy

NATO and Weimar countries should continue underlining the importance of the two structures and increasing their visibility by using traditional and social media channels, as well as increasing the accessibility to youth by offering more youth development programs. While NATO is currently investing heavily in public diplomacy efforts, Transatlantic Trends shows that these efforts do not necessarily reach the youth, as striking numbers do not even know what NATO is. Hence, the alliance should focus on formats popular among the youth, such as video content and podcasts. Furthermore, communications efforts should also be ramped up to demonstrate the success of international cooperation.

Given that Gen Z tends to view other countries as less reliable compared to older generations, these activities should focus on highlighting the benefits of collaboration and underlining those with concrete examples. Additionally, NATO offers only a limited number of places for internships and youth programs at the moment. In order to allow Gen Z to experience the importance of the alliance first-hand, NATO should increase the number of such programs and involve youth directly. Finally, NATO could also engage in more civic consultations, where youth attitudes towards the most important security issues would be collected.

Increase Civic Education about Future Challenges of a Changing World Order

All Weimar countries should invest heavily in civic education as Transatlantic Trends shows that Gen Z has limited knowledge of the current military deployments or the importance of NATO structures for the security of their countries. For example, Weimar countries and the United States could include more information about the Weimar triangle, as well as NATO structures in their national school curricula. Currently, only certain modules (such as particular history classes) include the information about the two but having a more extensive program would allow the youth to understand the importance of Weimar and NATO from a young age, and form a political culture marked by cooperation. Furthermore, increasing exchanges and even forming new ones, specifically for Weimar countries, would help to alleviate the issue of perceived reliability between the countries, and allow for smoother conversations about future challenges. A Weimar Youth Summit organized 30 years after the formation of the Weimar triangle could help identify key topics for a revitalized exchange between the three countries that is fit for the future.

Ensure that the Policymakers of Tomorrow Develop China Expertise

Addressing China’s influence is arguably the biggest geopolitical challenge of the 21st century for the Weimar countries and the United States. However, the question of how to engage with China will also be important when tackling issues such as climate change, human rights, and public health. In addition, Weimar economies rely heavily on trade with China. As such, it is pivotal that future decision-makers study Mandarin and the country’s political culture while also engaging critically with the country’s past and current developments. Ensuring that independent institutes offer language and culture programs is as important as safeguarding nuanced international media coverage and reporting from within the country. These efforts should aim to find a balance between constructive engagement with China without compromising core values and human rights. As such, the approach to China could serve as a start for a valuable exchange between Weimar countries and their Gen Z.