From Screen to Classroom: How Documentaries Help Children Understand Their Rights

Film is a powerful medium that can bring even the most complex issues within reach. This idea is fundamental to Docudays UA—a human rights documentary film festival in Ukraine whose team believes that dialogue on related topics should start early. That is why they launched a special initiative to screen documentaries in schools. During School DOCU/WEEK, children not only watch documentaries about but also discuss them and meet the filmmakers. We spoke to Yulia Kartashova, head of fundraising at the civil society organization (CSO) Docudays, and Nina Khoma, head of the DOCU/CLUB film club network, about why this work matters so deeply, even during the full-scale war.

How did Docudays begin and develop?

Yulia: The organization has existed for 27 years. It was founded in Kherson and was long known as Pivden (South). Later, it joined the team behind the International Human Rights Documentary Film Festival Docudays UA, which has become one of our main activities and gave the organization its current name—Docudays.

Even during the war, Docudays UA remains the largest documentary film festival in Eastern Europe. It keeps growing: the most recent, the 22nd festival in Kyiv, welcomed about 27,000 visitors.

As we developed, we realized we needed to reach beyond Kyiv, so we created a traveling human rights documentary film festival. Today, 29 CSOs across Ukraine co-organize it. We coordinate the network: provide films, ensure screening rights, support communication, logistics, and invite directors. Before the full-scale war, we covered all of Ukraine; now, we can hold events in 19 regions.

Our core mission is to talk about human rights through film.

This format helps explain complex topics in an accessible way. Eventually, we understood we could do this continuously. That’s how the idea of a film club network was born.

Nina: The network now includes over 520 film clubs across Ukraine, and it keeps growing. The demand has existed for a long time; the Revolution of Dignity accelerated it when many civic organizations asked for our films during Maidan.

Yulia: Film clubs get access to about 100 films on various human rights topics. At first, we only prepared subtitles, but later we added audio descriptions for people with visual impairments and special subtitles for people who are deaf or hard of hearing. Moderators also receive discussion scripts that we create with human rights experts.

Photo credit: NGO Docudays

Photo credit: NGO Docudays

So, the next logical step was School DOCU/WEEK?

Nina: Yes. Many of our film clubs were already based in schools, and we saw that our films fit well not only in informal but also formal education.

So, we asked ourselves: how do we let as many educators as possible know about this? We realized it needed a promotional format. That’s how School DOCU/WEEK appeared in 2019. Any teacher could apply, try the format, and then decide whether to continue. The first edition focused on bullying, the next on school democracy and student self-governance, and the latest one on volunteering—especially relevant during the full-scale invasion.

Yulia: We chose to work with schools also because we see it as our duty to work with children—our future. We also have film clubs at universities, libraries, and even in the penitentiary system, but helping children develop critical thinking and understand their rights and the value of democracy is essential for us.

We speak to children in their language, choose age-appropriate films, create game-based discussion scenarios, and gently embed important ideas.

And after School DOCU/WEEK, some schools decide to create permanent film clubs?

Nina: Exactly. Before the project we had under 100 school-based film clubs; now there are more than 170.

We also prepared a detailed methodological guide for teachers on integrating films into school subjects. Documentary films are a powerful tool: they show real people, relatable stories, and universal values. Children see peers from other cities and countries, compare experiences, open up, and start conversations.

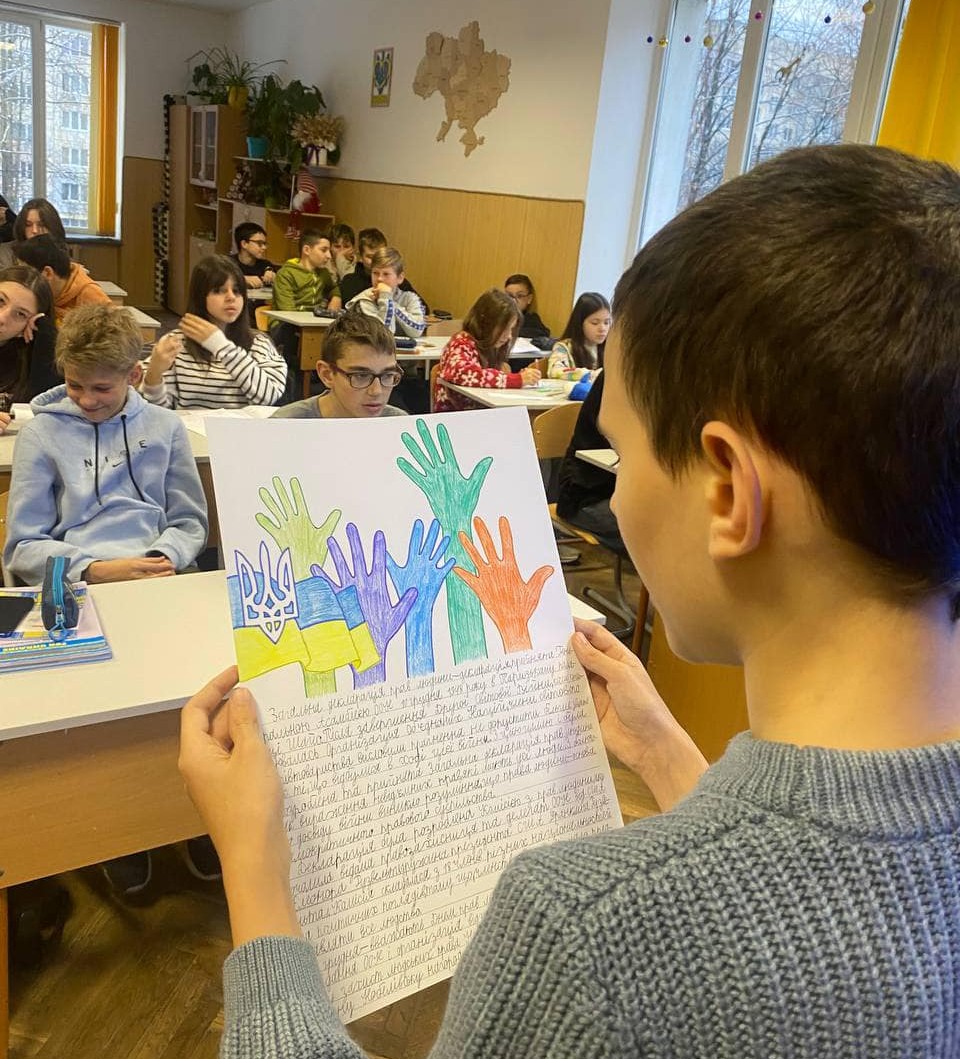

After screenings, children often do creative tasks, research topics, write letters to film protagonists, talk to directors, or connect with film clubs in other cities.

Photo credit: NGO Docudays

Photo credit: NGO Docudays

What feedback do you get from directors, who may not be used to such a young audience?

Nina: During a discussion, a student asked the co-director of Tales of a Toy Horse, Denys Strashnyi, about his goals and expectations. He replied that the meeting exceeded all his hopes. He was touched that students talked to him for an hour and a half, asked questions, and even recorded messages for the film’s protagonist.

Photo credit: NGO Docudays

Photo credit: NGO Docudays

Can you tell us more about the films chosen for the latest project?

Nina: There are many films about volunteers, so we wanted to show different types of volunteer experience. For example, Mova (Language) by Serhiy Lysenko is about volunteers bringing books to eastern Ukraine and promoting Ukrainian language and literature there.

Tales of a Toy Horse by Uliana Osovska and Denys Strashnyi follows a Ukrainian living in Tallinn who began traveling across Ukraine in 2014 to collect stories of kindness. He also collected drawings and small items to create a book, and he responded to specific requests for help from frontline areas and hospitals. This film shows how targeted, needs-based aid works.

There was also a touching moment: children from eastern Ukraine recognized their hometowns in the films—some places that now exist only in memory—and were grateful to see home again, at least on screen.

Euromaidan SOS by Serhiy Lysenko tells the story of our Nobel Peace Prize laureate, human rights defender Oleksandra Matviichuk. Together with students, we watched her activism evolve over the years and discussed her Nobel lecture.

How do you manage to continue your activities during the full-scale war, under shelling and blackouts?

Nina: COVID-19 trained us well and made us more resilient. Before the pandemic, we worked only offline due to copyright risks. But during COVID-19 we realized that “ We either go online or stop”. Within two or three weeks, we adapted the entire festival to an online format. After that, we applied the same format to film clubs. This experience helped a lot during the full-scale invasion.

School DOCU/WEEK was supposed to last a week, but that’s unrealistic during wartime. Now it runs for a month. Local organizers can adapt—they can move a discussion to another day or continue it in shelters if needed. The hardest part is scheduling director visits, so we look for venues with shelters and generators to make sure conversations can happen.

Funding is also a big challenge for many CSOs in Ukraine. What about you?

Yulia: DOCU/WEEK can only happen if we secure funding. We look for it every year because we love this format. We have institutional grants covering administrative costs but we must find extra funding for coordinators, teacher training, film acquisition, and promotion. The latest DOCU/WEEK was possible thanks to GMF and Global Affairs Canada.

What do you see as the main result of School DOCU/WEEK?

Nina: The key achievement is that teachers see the format works and want more. Many now design their own systematic school-wide formats and aim to reform education. One teacher created a psychosocial support program for children affected by war, including those who lost parents or were evacuated. Another realized she wanted not only to work with children but also to train other teachers on cyberbullying, with support from psychologists. These are examples of how new activists emerge. Our project coordinators themselves are schoolteachers who decided to grow as managers of a national project.

Students who volunteer at our festival often tell me they used to be the schoolkids watching our films. Former students approach us at trainings too.

Yulia: School DOCU/WEEK creates an atmosphere of support and open dialogue in schools. Formal lessons don’t always allow for such honest conversations. It’s hard to measure this impact, but it is, in my view, the most valuable part.

Video credit: NGO Docudays