Urban Projects in Wartime: How Eco Misto Chernihiv Adapts and Helps

Eco Misto Chernihiv, a civil society organization in Ukraine, used to work on typical urban projects: teaching residents how to sort waste, creating recreational spaces, and developing cycling infrastructure. Following the start of the full-scale Russian invasion and the partial occupation of the region, it seemed that such initiatives would fade into the background. But the experience the activists had gained through their work turned out to align perfectly with volunteering needs in wartime. We spoke with the head of the organization, Serhii Bezborodko, about why urban projects remain essential even during wartime.

When and why was Eco Misto Chernihiv founded?

The organization was officially established in 2016, though for two years before that we had operated as a volunteer initiative. After returning to Chernihiv from the Revolution of Dignity in Kyiv, I felt a strong need to live more consciously. I started organizing volunteer clean-ups and encouraged friends to join. We met every weekend for a year and eventually became part of the national youth movement Let’s Do It Ukraine, which I coordinated in Chernihiv.

Over time, my circle changed, and I learned about the legal framework for civil society organizations. I was an engineer by training and worked as a photographer so I knew little about the sector, but I was sure I wanted to create change rather than wait for it. So, in 2016, several activists and I founded Eco Misto.

How did you define your early areas of work?

We started by cleaning public spaces and quickly realized that the waste we collected needed to be sorted. That led us to work on recycling. Then came collecting hazardous waste, like used batteries, and public awareness campaigns. New challenges kept expanding our focus: for example, while cleaning one of the parks, we learned it was at risk of development, so we stepped in to protect it.

As we gained experience in advocacy and defending public spaces, urbanism naturally followed. We wanted to improve these areas—planting alleys, creating street furniture, designing public spaces. This is how the first community garden in Chernihiv appeared.

What does Eco Misto do today?

We now have several key directions. One is sustainable mobility—a response to the full-scale war. At the beginning of the invasion, Chernihiv temporarily lost public transport and fuel supplies, and bicycles became essential. Even after the situation stabilized, we stayed in this field.

Our organization co-founded the national Bikes for Ukraine initiative, which sources used bikes from abroad, repairs them locally, and donates them to volunteers, social workers, doctors, displaced people, and sometimes the military. Over two years, we repaired and distributed more than a thousand bicycles, and their presence has become clearly visible across the city.

Photo credit: NGO Eco Misto Chernihiv

Another focus is still waste sorting and recycling. We created Plastic Fantastic: a small social workshop that turns sorted plastic into new items.

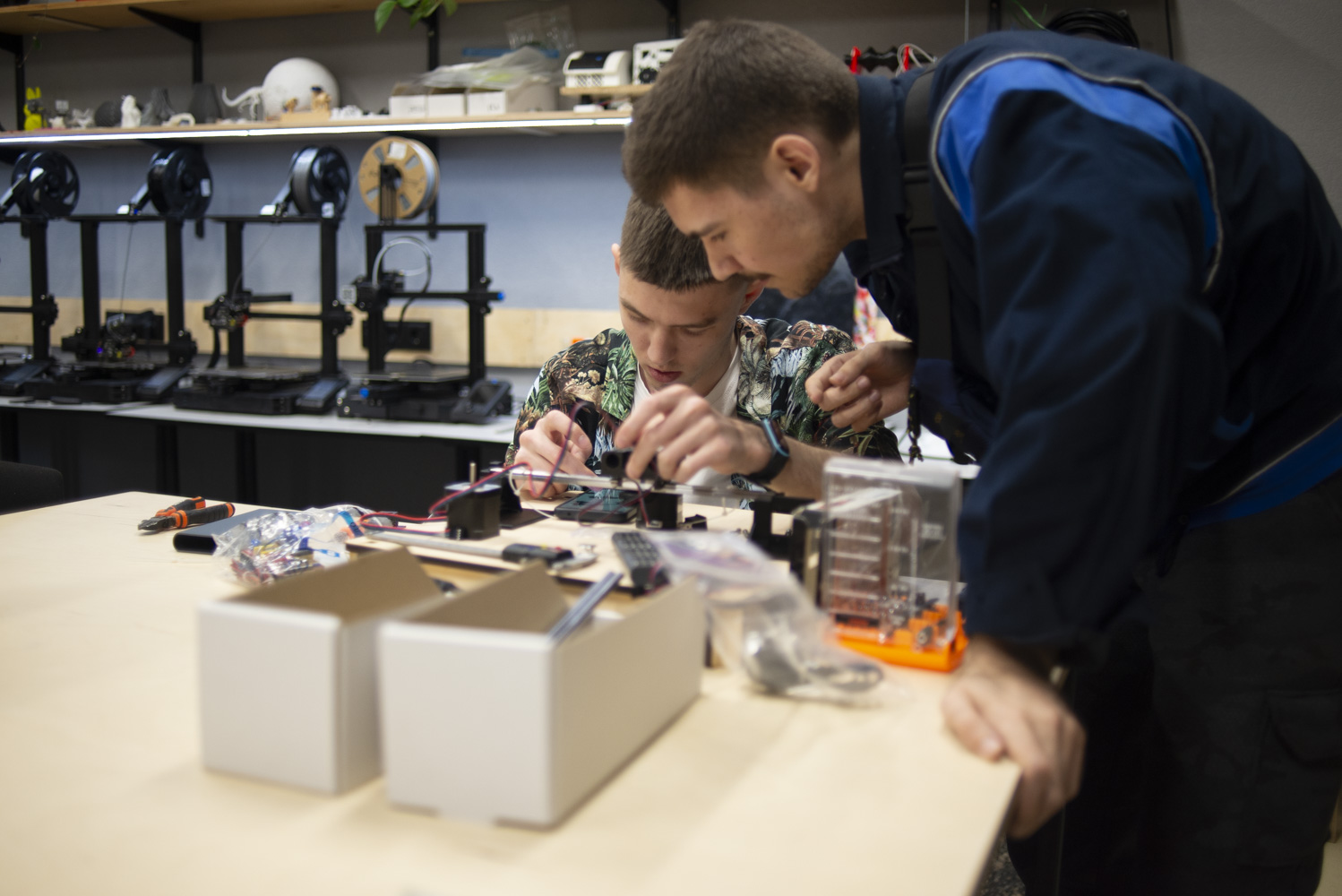

We also run a makerspace with the local university, teaching and learning hands-on skills. It’s equipped with everything from hammers to a laser cutter. We host workshops and community build days because the blockade of Chernihiv showed us how important self-reliance is, whether it’s making fire, purifying water, or generating electricity.

How did your work change at the beginning of the full-scale invasion, when it seemed that environmental or urban initiatives were no longer a priority and the main task was simply to survive?

Right before the invasion, we had launched a public sorting station on the grounds of an abandoned university campus. We accepted 25 types of packaging but operated only a couple of months before losing access due to heavy shelling. Still, our community stayed active online, looking for ways to help.

We donated whatever equipment we had—heaters, drills, shovels, nails—to the Territorial Defense and the military. And we joined a volunteer effort that provided door-to-door help to vulnerable residents via a mobile app originally designed for food delivery. Each morning, we logged into the app, checked requests in our neighborhoods, and delivered medicine, food, and hygiene items. That’s when bicycles became essential. And it soon became clear that we needed more of them. With partners across Europe, and seeing similar needs in other frontline regions, we launched the Bikes for Ukraine initiative I mentioned earlier. The first 200 used bicycles arrived from Lime Bike. Chernihiv’s trolleybus depot gave us space to repair them, and we delivered the bikes to recently de-occupied or heavily affected communities.

As the number of bikes grew, we opened a social repair workshop. It started with hired mechanics but now anyone can come in, grab the tools, and fix their own bike.

At what point did making become another direction for your organization?

A turning point came in 2023, when the mobile makerspace Tolocar visited Chernihiv. That’s when we discovered the concept of making and realized that much of what we’d been doing all along was actually maker work. We thought we were just fixing things and building stuff from pallets but it turned out we’d been makers without knowing it. Eventually we became Tolocar’s long-term partner and co-founded a makerspace called Peremoha Lab.

We opened the makerspace in a former cinema: it’s 40 years old, has about 40 problems, and we’ve already invested around UAH 40 million into repairing and equipping it. Now it hosts four workshops and a solar power station. We’re renovating the second floor ourselves because demand from students is so high. We believe in in-person learning: research is valuable but not when it sits in a drawer. We build prototypes, test ideas, gain experience—and experience is everything.

Photo credit: NGO Eco Misto Chernihiv

We are currently implementing a GMF-supported project called Professions of the Future: five career orientation courses for high-schoolers and first-year students. They cover modern fields like urbanism, 3D scanning, and using AI in architecture.

Many families have evacuated young people to other regions or abroad. But if Chernihiv loses its youth, the city loses its future. Our goal is to inspire students through our community and makerspace so they choose to stay and study here.

How do you manage your activities under the current security conditions and the ongoing outflow of young people?

With constant attacks on critical infrastructure, air-raid sirens sometimes never stop. The makerspace has a shelter, which we’re transforming into a multifunctional space together with students.

And the outflow of youth is no excuse for doing nothing—many young people remain, and they still need opportunities. Facebook ads don’t reach them, and even Instagram isn’t effective unless everything works in one click. So, we put up posters with QR codes at universities—an old-school method, but it works, because that’s exactly where our key audience is. We also rely on a strong network of teachers who help spread the word about our activities

What has the funding situation been like for you in recent years?

We always lack funding because our ambitions are big and we want to run many projects. Yet we know we can only manage two at a time—our human resources are limited. Three team members have been mobilized and some others have left the region.

Donors continue to support the Chernihiv region because it has suffered heavily from the war. But what we lack most is institutional support, as many donors fund only specific projects. We also try to engage our community—for example, raising money for a battery for our solar power station—but we cannot rely on crowdfunding endlessly. Some people need batteries while others collect donations for medical tourniquets for soldiers.

And people also prefer to donate toward tangible things: a battery makes sense; two months of a financial manager’s salary does not.

We try to sell items made at Plastic Fantastic, but we’ve only mastered making them beautiful—not selling them. After all, we’re activists, not businesspeople or marketers.