Threats to Democracy: City Edition

To strengthen any institution, you must first identify its weak points. Following the launch of the Cities Fortifying Democracy (CFD) Project, GMF Cities surveyed a diverse group of city managers, public-safety officials, journalists, and activists to better understand what they perceived to be the greatest threats to democracy in their cities. Though there were transatlantic differences, a clear common message emerged: when the people do not work together, democracy dies. Time and again, city officials observed that residents who are wary of government are gravitating toward extreme views (polarization) or dropping out of the process entirely (low participation in elections and other forms of civic activity). Both of these trends are dysfunctional and incompatible with democratic survival. And it is up to citizens and governments alike to cultivate a democracy grounded in respectful—yet robust—public engagement.

In the survey, GMF Cities asked project participants to rate the seriousness of a variety of threats to democracy, including factors from suffrage restrictions to lack of government transparency. There was transatlantic agreement that lack of trust between public safety officials and residents and the proliferation of misinformation (false information that is spread, regardless of intent to mislead) were among the top threats. However, there were also transatlantic differences. Europeans were more concerned about resident participation (excluding elections) and transparency, while Americans were more concerned about poor civic education, low voter turnout, and an unfair justice system.

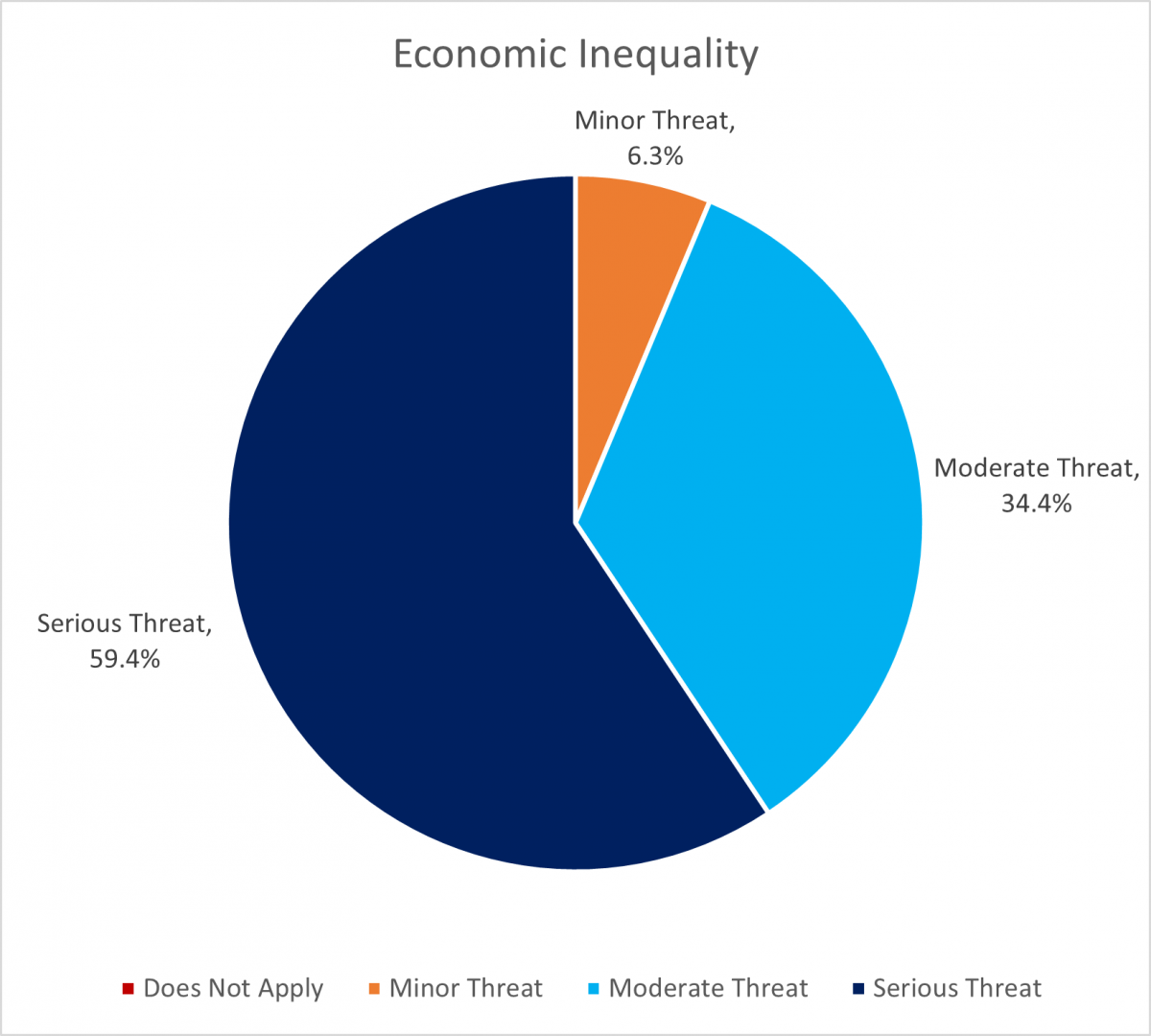

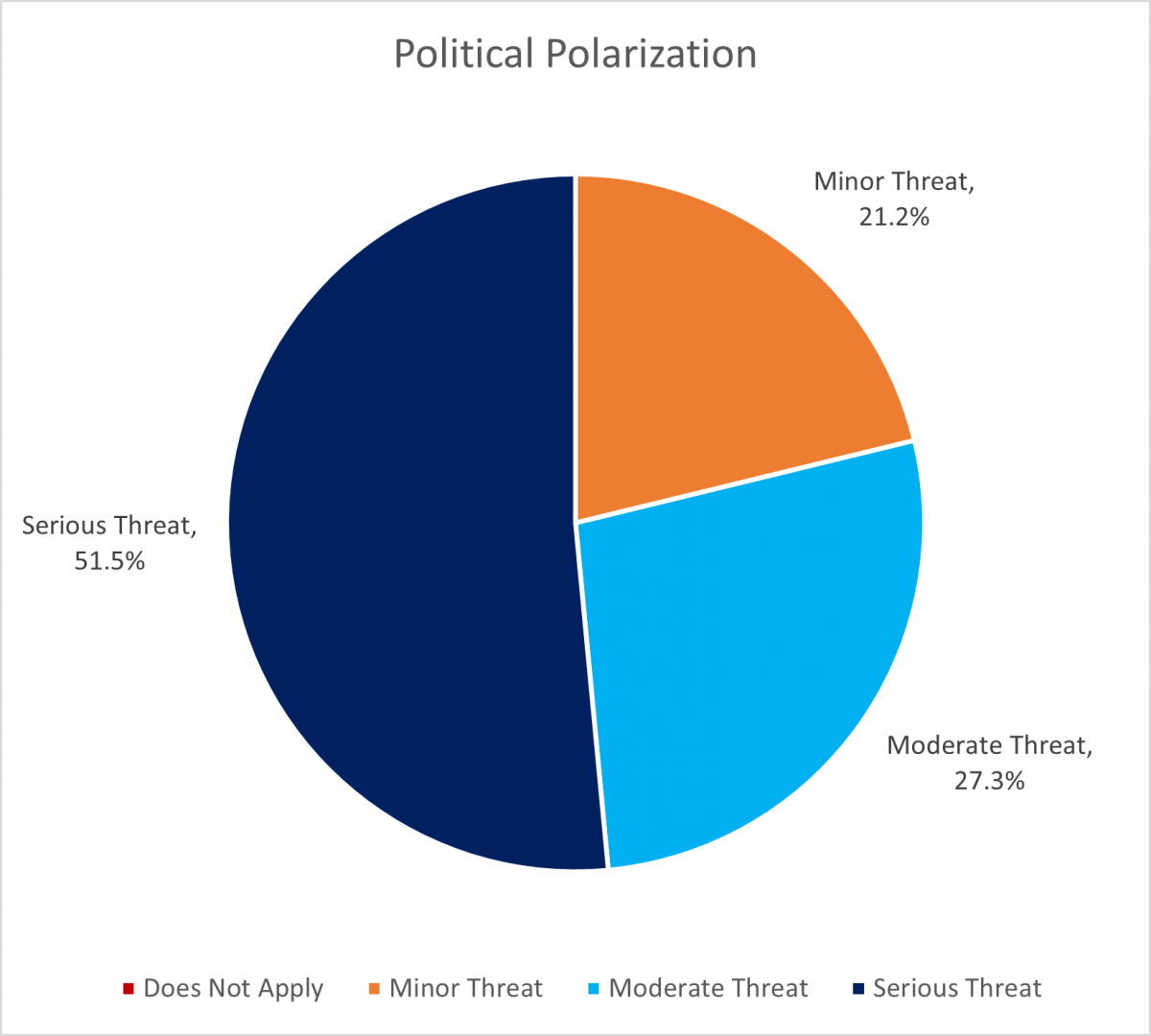

In terms of the social and economic characteristics, economic inequality was the factor most likely to be cited as a “serious threat” (59.4 percent) to democracy, followed by political polarization (51.5 percent). A majority of participants also said class (78.7 percent) and racial or ethnic divisions (75.7 percent) posed either “moderate” or “serious” threat to democracy in their cities. Just over half (51.5%) said that geographic divisions were at least a moderate threat, while religion was the least likely factor to be considered a threat (a majority said it was either a minor threat or did not apply).

During the first small-group workshop, which included the leaders and managers in local government from ten of the cohort cities, the discussion drew inspiration from the survey findings and focused heavily on participation and polarization. Several members of the cohort discussed the difficulty of managing residents’ expectations and how that can lead to a breakdown in mutual trust. Some of the residents who express a desire for massive, rapid changes are not fully aware of the implementation challenges faced by city staff, including bureaucratic hurdles and limited resources. Strategies for facilitating strong, two-way communication that fosters trust were a major discussion topic in the session, and one which the project will explore in greater depth in future convenings.

Cohort participants also noted the growing divide between a group dominated by young, ethnically diverse renters and older, whiter, wealthier homeowners—a trend in line with their responses in the survey’s threat assessment. The competing interests of these groups, as well as the fact that factors like wealth and race often stack up to deepen divides, has made it harder to find common ground.

A key question raised was: How can cities adapt to act more quickly without risking their systems of collaboration and consultation in the process? Though it has been exciting to have new enthusiastic and diverse voices join public discussions, cities are not necessarily equipped to respond to their sense of urgency and to revise necessarily deliberative processes. The project will delve deeper into strategies for approaching this paradox in future sessions, while also addressing other issues that came through in the survey, such as more effective engagement of marginalized populations, ensuring that engagement leads to tangible results and long-term relationship-building, and encouraging cooperation and healthy competition between rival interests in a polarized world.

Though there are no simple, one-size-fits-all solutions to these problems, the Cities Fortifying Democracy workshops have given the participating cities a window into their peers’ struggles and strategies. Through these private discussions and public events, the Cities Fortifying Democracy project hopes to spark conversations and inspire new approaches that practitioners, anywhere, can bring to their daily work.