More Representation But Not Influence: Women in the European Parliament

Summary

Representing more than 447 million people across 27 countries, the European Parliament should be the poster child for the European Union’s “united in diversity” motto. However, the representation of women in the parliament and its key positions remains weak and change is slow. While the parliament has seen a steady increase in the proportion of female members (MEPs) over the years, from 16% in 1979 to 39.5% in 2021, this is far from the whole picture when it comes to women’s representation.

The European Parliament claims to be an early advocate of gender mainstreaming in policymaking to tackle the barriers faced by women in being visible and recognized, yet it is more discriminatory than meets the eye. It lags on meeting its own goals. Not only does gender equality vary drastically across its country and political groupings, the informal structures and power plays within the institution and in interactions with stakeholders in other EU institutions demonstrate that it is not always living up to its claims.

In order to understand why gender representation in the European Parliament remains imbalanced, it is necessary to unpack and analyze the institution, including its committees and subcommittees, and country and political groupings. With the mid-term rotation in committee chairs due in early 2022, now is a good time to look more closely at the gender balance in this institution.

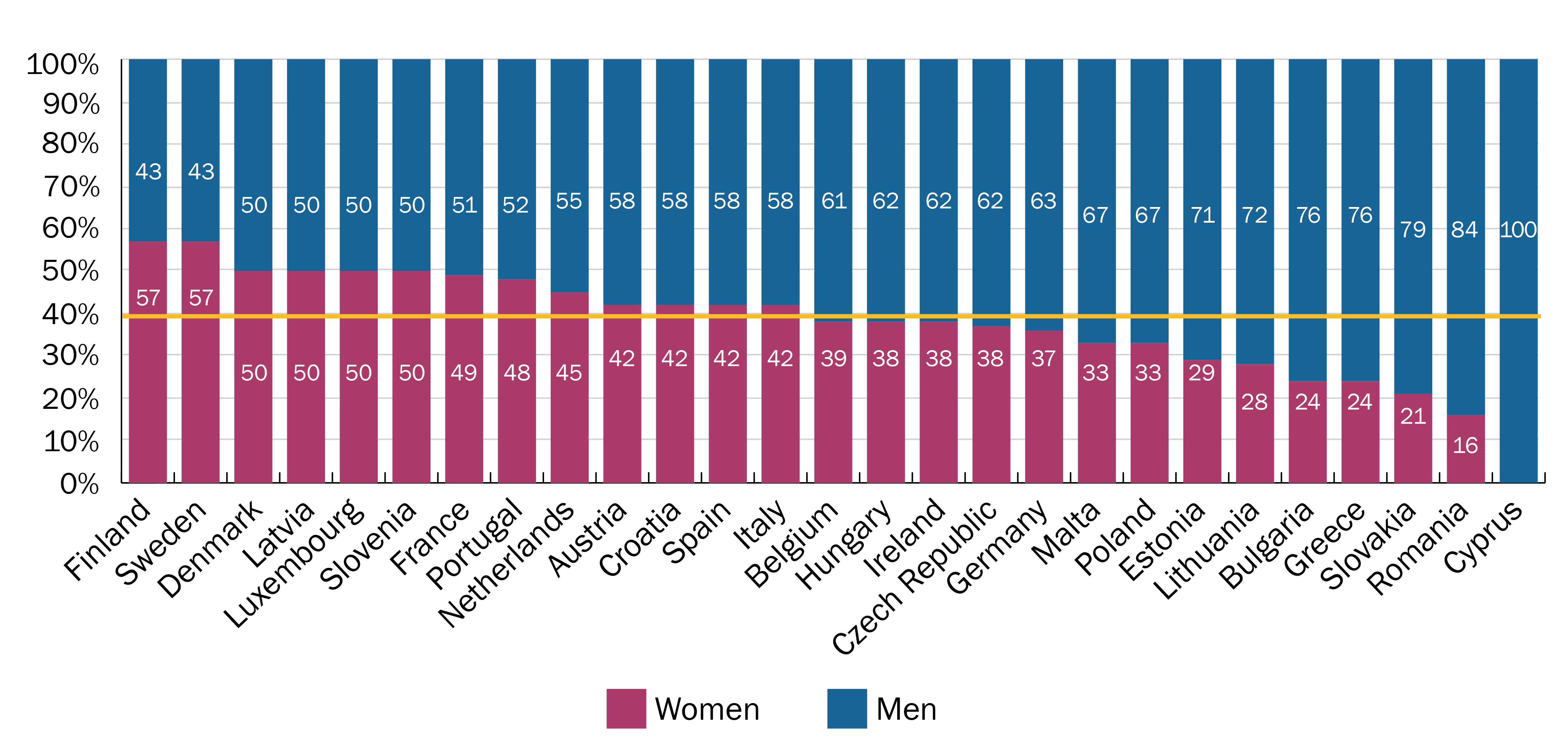

In 2019, 308 women were elected to the parliament, taking women’s representation to its highest level of 41%, a figure that with Brexit later dropped to 39.5%. Only Finland and Sweden have a majority of women MEPs, while Denmark, Latvia, Luxembourg, and Slovenia have achieved parity. This shows that gender mainstreaming is not fully internalized at the member-state level, making it more difficult for the least equal countries to follow the EU’s standards toward gender equality in their parliamentary representation.

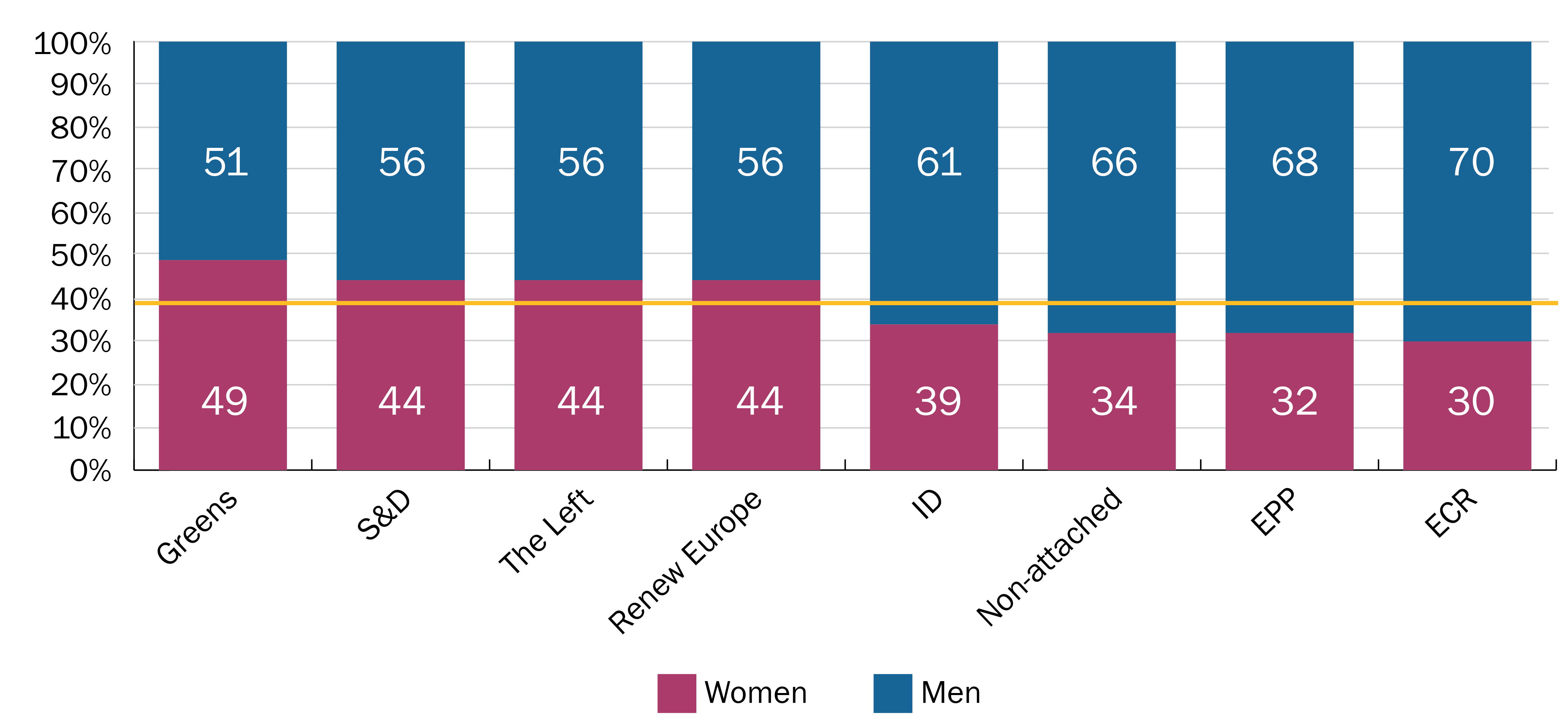

The representation of women differs across the political groups in the European Parliament. The most gender-equal one is the Greens/European Free Alliance group with 49% of its MEPs being women, followed by other left and center groups, with the more right-wing groups—Identity and Democracy, the European People’s Party, and the European Conservatives and Reformists—having higher male representation.

The increase in the number and proportion of women in the European Parliament has not been fully reflected in the composition of its committees. The distribution of men and women in committees has remained relatively unchanged, albeit with significant differences between the proportion of women in the parliament and the proportion of women in committees. Women’s representation has increased by between 10% and 30% across all committees between the previous and the current term. Only three committees come close to gender parity. In some committees, the share of women members has even decreased. There has also been a decrease in the proportion of female committee chairs. No clear trend can be distinguished in terms of which committees are chaired by women, with a mix between monetary, social, and defense policy areas. Among those political groups with more than one committee chair, the Greens stand out for having only women committee chairs. The group nearest to gender parity in this regard is the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats, also closely reflecting its gender composition of the group in the parliament. Overall, between the previous and the current parliamentary terms, for some groups the match between its overall gender composition in the parliament and in that in committees has become less.

A mix of external and internal factors is at play when it comes to questions of gender balance in the European Parliament. The external factors shape its overall composition and there is little it could do to address them. The internal factors relate to the workings of the European Parliament, its composition, and the political groups. Therefore, the parliament, and in many cases individual political groups, could address and remedy them if they decided to do so.

Download the full policy paper

Introduction

The imbalance between men and women in political empowerment and in political office is a worldwide phenomenon. In Europe, equality in this regard is still not achieved. Even if in all EU member states women have acquired the right to vote and to engage in political life, they continue to be underrepresented in politics and more broadly in public life, including in national parliaments and governments, local assemblies, and the European Parliament. Besides the attention paid to women during election cycles, actions taken toward sustainable change remain disorganized and inconsistent. Representing more than 447 million people across 27 countries, it may seem that the European Parliament is the poster child for the European Union’s “united in diversity” motto. It should be representative of the fact that just over half of the EU population consists of women, but the representation of women in the parliament and its key positions remains weak and change is slow.

The European Parliament claims to be an early advocate of gender mainstreaming in policymaking to tackle the barriers faced by women in being visible and recognized. In adopting the UN Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action in 1995, it stated its intention to improve the gender balance in the leadership of its committees and delegations as well as in the appointment of external experts for panels or as authors of studies. The parliament launched gender-mainstreaming initiatives—including the creation of the Women’s Rights and Gender Equality committee (FEMM) in 1984—that were supposed to ensure integration of the gender dimension in its work.1 In 1996, the High-Level Group on Gender Equality and Diversity was created to focus on the promotion of diversity and equal representation of women and men at all levels in the parliament.2 In 2020, the EU’s first Gender Equality Strategy set out a vision of gender mainstreaming and aimed to tackle issues such as gender-based violence, gender pay gaps, healthcare, and decision-making.3 In 2021, the European Parliament adopted a “roadmap to achieve gender equality in political processes and its administration” and stated its intention to become a “front-runner” in terms of gender equality among EU bodies with the creation of a gender-balanced Europe by 2025.4

However, all of this hides the reality of an institution that is more discriminatory than meets the eye. A closer look reveals that the European Parliament lags on meeting its own goals. Not only does gender equality vary drastically across its country and political groupings,5 the informal structures and power plays within the institution and in interactions with stakeholders in other EU institutions demonstrate that it is not always living up to its claims.

In order to understand why gender representation in the European Parliament remains imbalanced, it is necessary to unpack and analyze the institution, including its committees and subcommittees, and country and political groupings.

The increase in the number of women in the European Parliament over the years has not been fully reflected in the composition of its committees. For example, in May 2021, the #SHEcurity campaign pointed out that women accounted for less than 20% of the Foreign Affairs Committee between 2000 and 2019, and that between 2004 and 2019 the Subcommittee on Security and Defense had the lowest proportion of women of all the committees.

In order to understand why gender representation in the European Parliament remains imbalanced, it is necessary to unpack and analyze the institution, including its committees and subcommittees, and country and political groupings. With the mid-term rotation in committee chairs due in early 2022, now is a good time to look more closely at the gender balance in this institution.

Information from the websites of the European Parliament6 and the political groups in it, as well from individual contacts in committee secretariats, was used to compile the data for this paper. The analysis of committees includes full and substitute members. The data is broken down to analyze the situation regarding chairs, vice-chairs, and members of committees as well as the nationalities and political group affiliation of members. For each committee and subcommittee included the proportion of women to men, the leadership positions they hold, and their nationalities and parties were analyzed.

The Gender Balance in National Representation

Over the past years, more women have entered the European Parliament. In 2019, 308 were elected to it, taking women’s representation to its highest level of 41%, a figure that with Brexit dropped to 39.5%.7 However, even if women’s representation in the parliament today is higher than the global average (25.5%) and the average for the national parliaments of EU countries (30.4%), men are still overrepresented at 60.5%. This is a slight improvement from the previous parliamentary term when this figure was 63%.

Only Finland and Sweden have a majority of women MEPs, while Denmark, Latvia, Luxembourg, and Slovenia have achieved parity. (See Figure 1.) At the opposite end of the spectrum, Bulgaria, Greece, Slovakia, and Romania have the lowest proportions of women while Cyprus has no women MEP.

Contrary to what might be expected, the countries that have the highest share of women in their representation—Finland and Sweden—do not have gender quotas for European Parliament elections. Those countries that have some form of quota or restrictions against single-gender lists for European Parliament elections have significantly varying shares of women in their representation, with some far from achieving parity: Luxembourg (50%), Slovenia (50%), France (49%), Portugal (48%), Spain (42%), Croatia (42%), Italy (39%), Belgium (38%), Poland (33%), Greece (24%) and Romania (16%). This is probably due to the differing types of quotas or restrictions in place as well as disparate equal representation standards.

These figures show that gender mainstreaming is not fully internalized at the member-state level, making it more difficult for the least equal countries to follow the EU’s standards toward gender equality in their European Parliament representation. Since 2003, gender-mainstreaming initiatives monitored by the FEMM committee have come with recommendations for member states. However, there are discrepancies among them when it comes to capacity to act upon these recommendations, with some lacking tracking systems or initiatives for institutional gender mainstreaming. For example, the promotion of gender equality through policy and legislation is a relatively recent phenomenon in Cyprus.8 By contrast, in Denmark, which claims to have a culture of equality, women represent 40% of members of the national parliament and the government has a minister of equality, whose duties include to initiate and to monitor gender-representation initiatives.9

Figure 1. Men and Women MEPs by Country, 2021

The Gender Balance in Political groups

The representation of women differs across the political groups in the European Parliament, with an average of 39.5% in 2021. (See Figure 2.) The most gender-equal one is the Greens/European Free Alliance (EFA) group with 49% of its MEPs being women. Next come The Left (formerly the Confederal Group of the European United Left/Nordic Green Left), Renew Europe (formerly the Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe—ALDE), and the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats (S&D) with 44% each.

There is a left-right divide, with the more right-wing groups—Identity and Democracy (ID), the European People’s Party (EPP), and the European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR)—having higher male representation.

Figure 2. Men and Women MEPs by Political Group, 2021

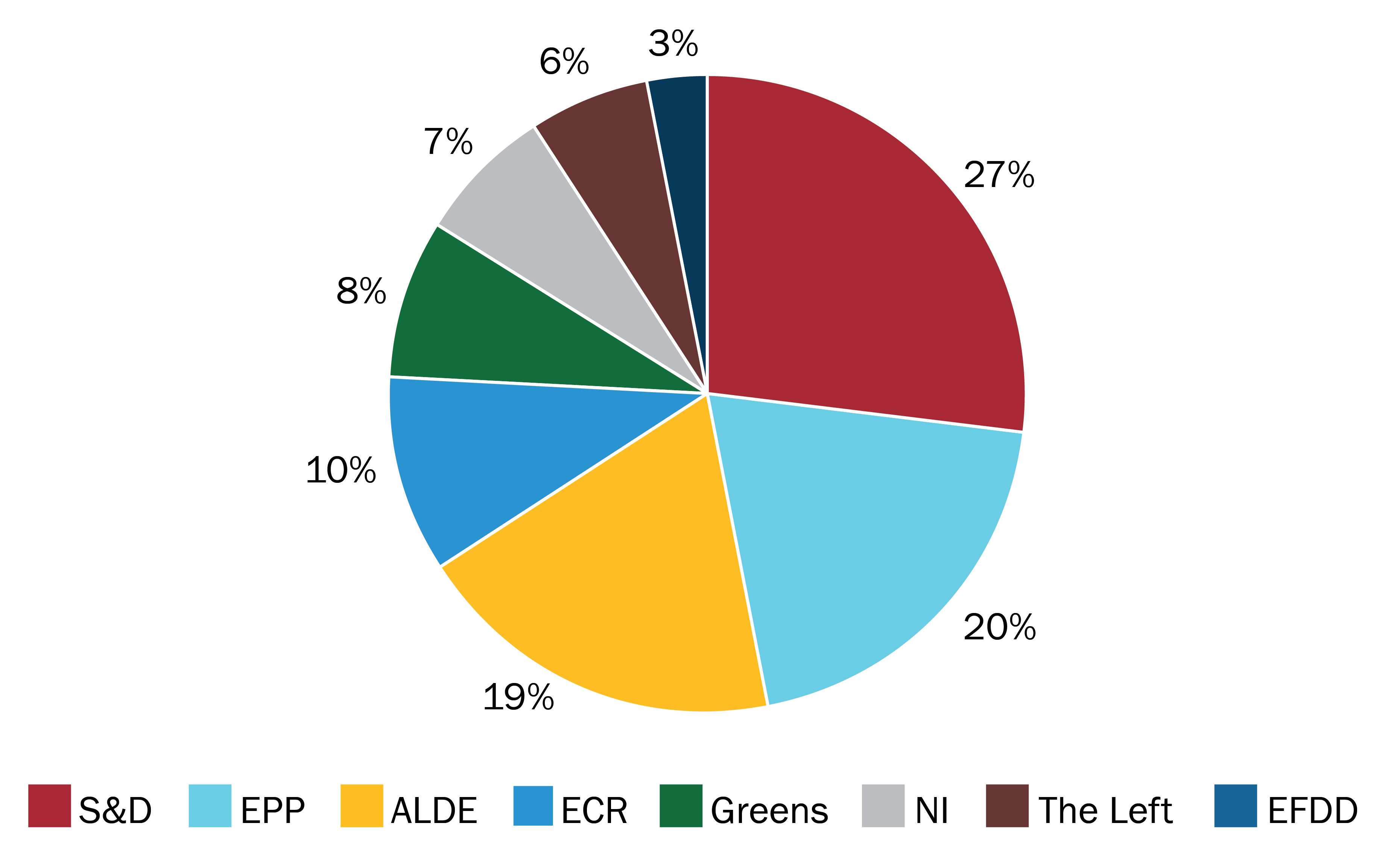

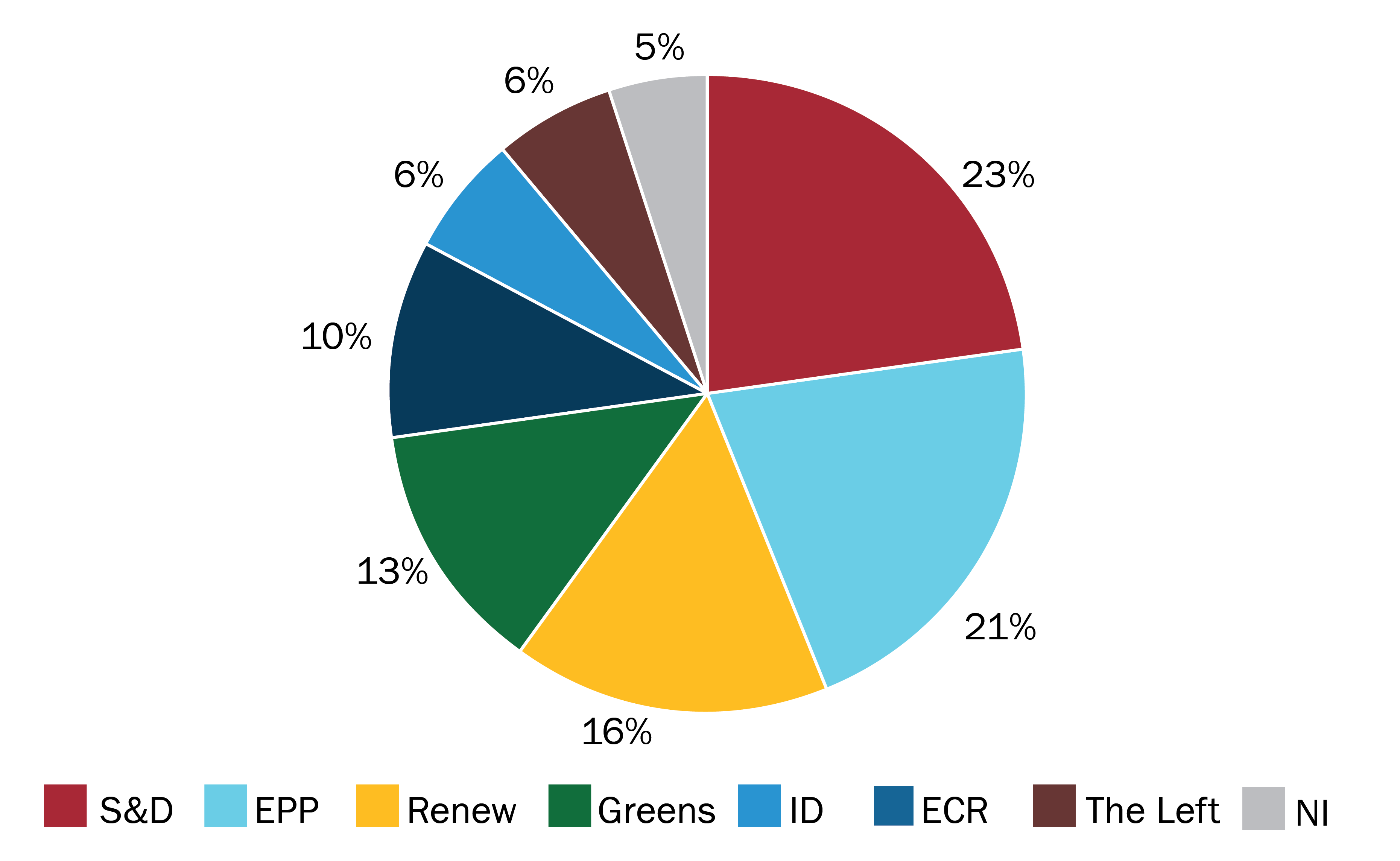

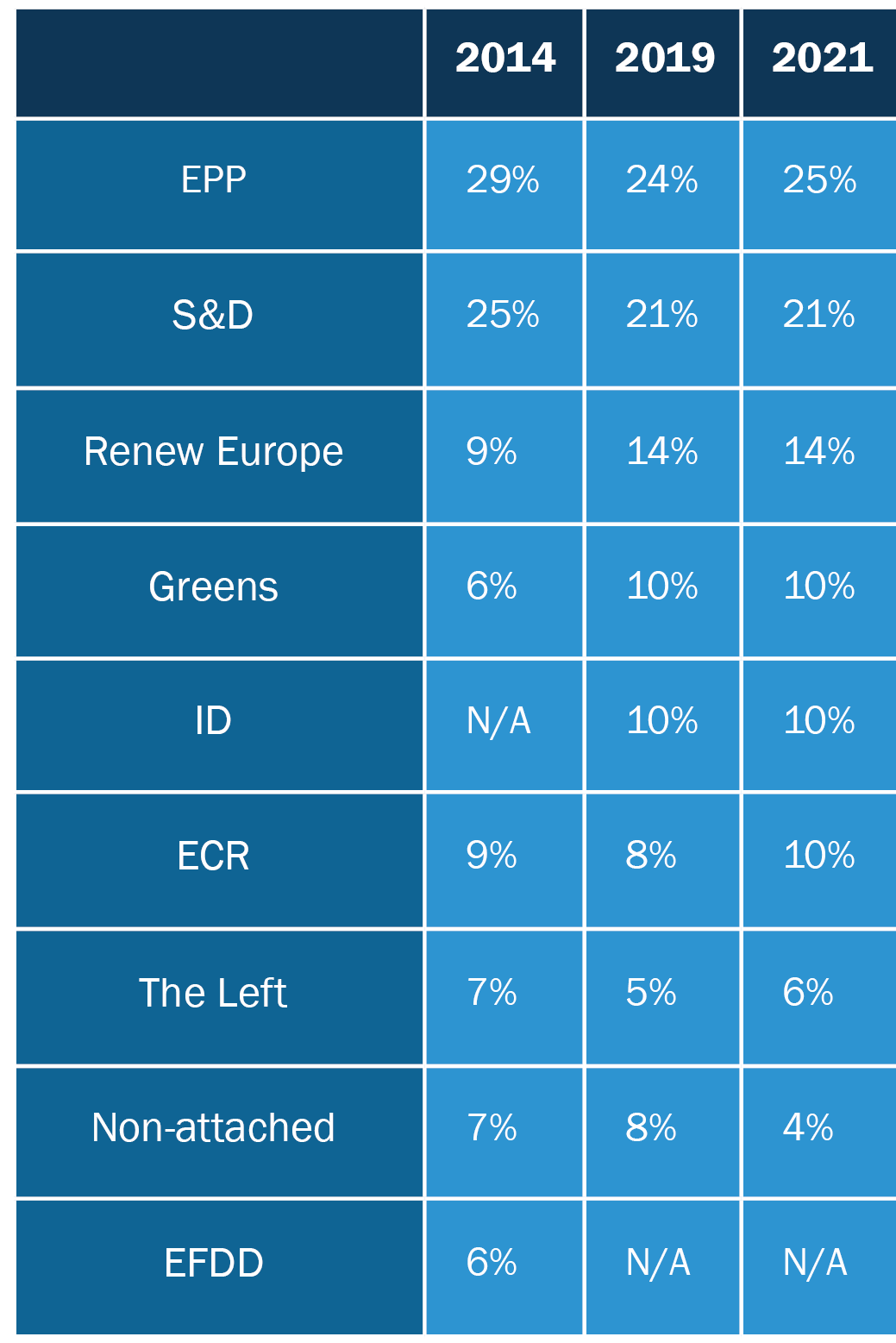

When looking at each political group’s share of the number of women MEPs, The Left and the non-attached accounted for the lowest share in the previous and current parliament, and the S&D group the largest. (See Figures 3 and 4.) The Greens group and the ID group (the successor to the Europe of Nations and Freedom group) account for a greater share of women MEPs compared to in the previous parliament as their overall number of MEPs increased (Table 1). In comparison to 2014, the EPP group accounts for 1% more of women MEPs, the ID group for 7% more and The Greens for 5% more. By contrast, the S&D, ECR, and ALDE/Renew Europe groups now account for a smaller share of women MEPs than they did in the previous parliament, despite accounting for the same or a greater share of MEPs. (See Table 1.) The ECR group today has a higher proportion but a much reduced one of women MEPs as a result of the change in the group’s composition due to Brexit.

Figures 3 and 4. Political Groups’ Share of Women MEPs, 2014 and 2019.

Table 1. Political Groups’ Share of MEPs.

The Gender Balance in Committees and Subcommittees

Women’s representation in the European Parliament’s committees has increased from an average of 37% in the previous term to one of 39.5% in the current term. While no committee has gender parity, three come close to this goal. Women make up 49% of the Committee on the Environment, Public Health and Food Safety (ENVI), up from 42% in the previous term. The Special Committee on Beating Cancer (BECA) and the Committee of Inquiry on the Protection of Animals during Transport (ANIT), which are new ones, are both made up by 48% of women. However, all these committees have a greater percentage of women than the average for all the committees.

Some committees have an overrepresentation of women. In the previous parliamentary term, women made up the majority of only the FEMM committee. By contrast, in the current term, women are a majority in three: the Committee on Development (DEVE) with 53%, the Committee on Employment and Social Affairs (EMPL) with 54%, and the Committee on Women’s Rights and Gender Equality (FEMM) with 89%.

In comparison to the previous term, women’s representation has increased by between 10% and 30% across all committees in the current term. (See Figures 5 and 6.) During the previous term, the proportion of women in FEMM was significantly higher than that of men (70%), and it has increased in the current term (89%). The most significant shift in gender composition of any committee has been in DEVE, with women’s representation increasing from a minority of 20% to a majority of 54%. Other committees that have seen a significant increase (more than five points) in the representation of women include the ENVI committee, from 43% to 49%, the EMPL Committee from 47% to 54%, the REGI Committee from 32% to 44%, and the Committee on Culture and Education (CULT) from 40% to 43%. Meanwhile, the proportion of women in the Committee on Constitutional Affairs (AFCO) dropped from 20% to 18%, in the Committee on Budgets (BUDG) from 26% to 23%, in the Committee on Economic and Monetary Affairs (ECON) from 31% to 30% and in the Committee on Transport (TRAN) from 38% to 37%.

The committees with the highest proportion of men are the AFCO committee (82%), the BUDG committee (77%), and the Committee for Foreign Affairs (AFET) (75%). (See Figure 6.) BUDG carries significant weight as the parliament can stop the EU budget process. AFET has less direct impact on EU legislation and budgets, but its members have plenty of media opportunities. It is a sought-after committee among MEPs who formerly held high positions in their countries. AFCO is often more important than BUDG on internal matters as it deals with institutional and constitutional matters.

Figure 5. Proportion of Men and Women in Committees, 2014.

Figure 6. Proportion of Men and Women in Committees, 2021.

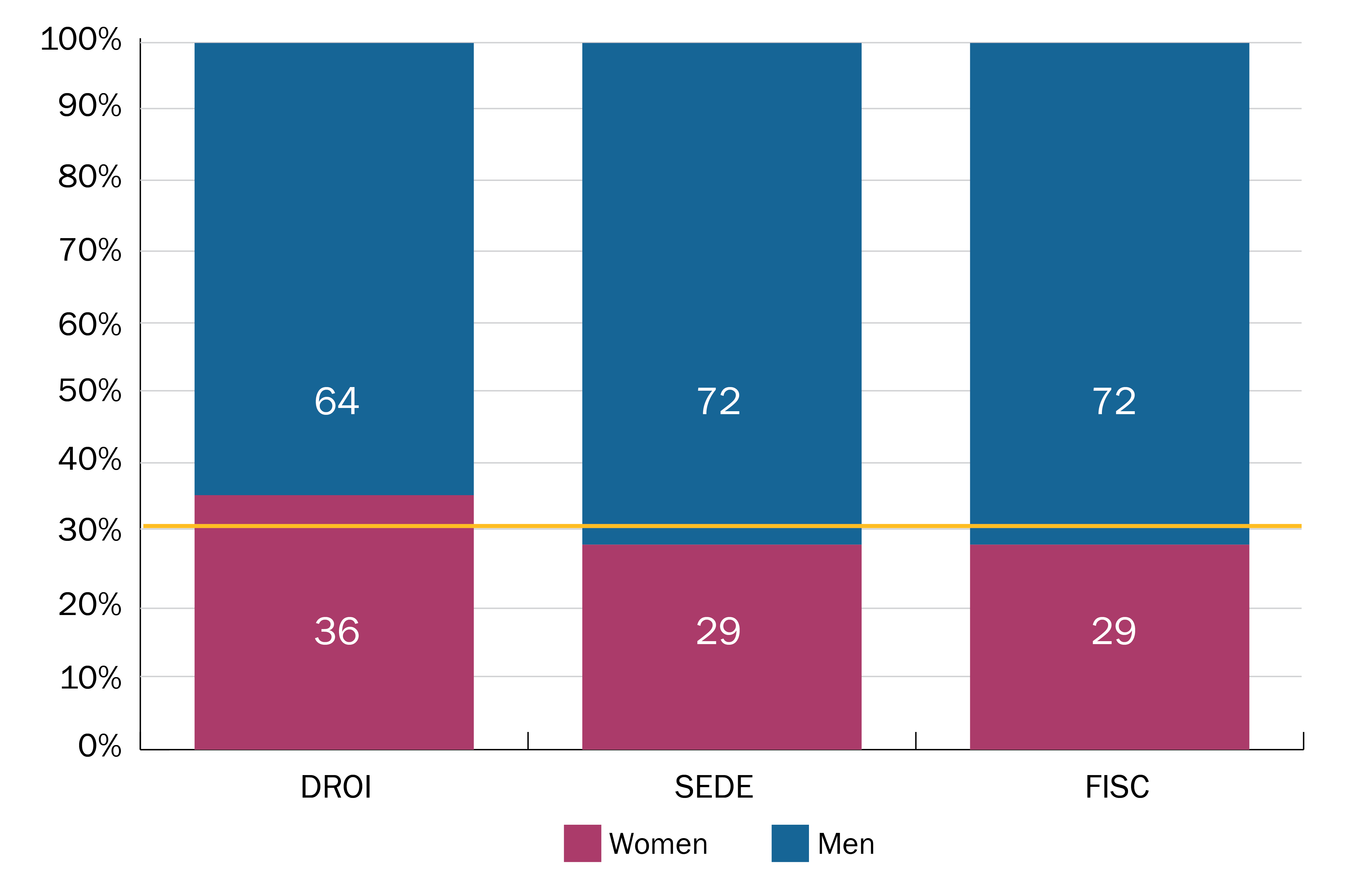

Among the three subcommittees, women make up 36% of the Human Rights Committee (DROI), making it the closest of the three to gender parity and relatively close to the overall proportion of women in parliament. The subcommittees on Security and Defence (SEDE) and Tax Matters (FISC) have 29% women each. (See Figure 7.) The difference between SEDE and DROI is interesting, as both are subcommittees to AFET, which has one of highest proportion of men among committees.

Figure 7. Proportion of Men and Women in Subcommittees, 2021.

Women’s representation is higher, and above the overall parliament average, in the special committees on Beating Cancer (BECA) at 50% and on Artificial Intelligence in a Digital Age (AIDA) at 45%. The Special Committee on Foreign Interference in all Democratic Processes in the European Union, including Disinformation has 34% women members. This is perhaps no surprise as it evaluates threats of domestic and foreign interference in the democratic process, which often use societal issues around women’s rights to polarize societies.

The Gender Balance Among Committee Chairs

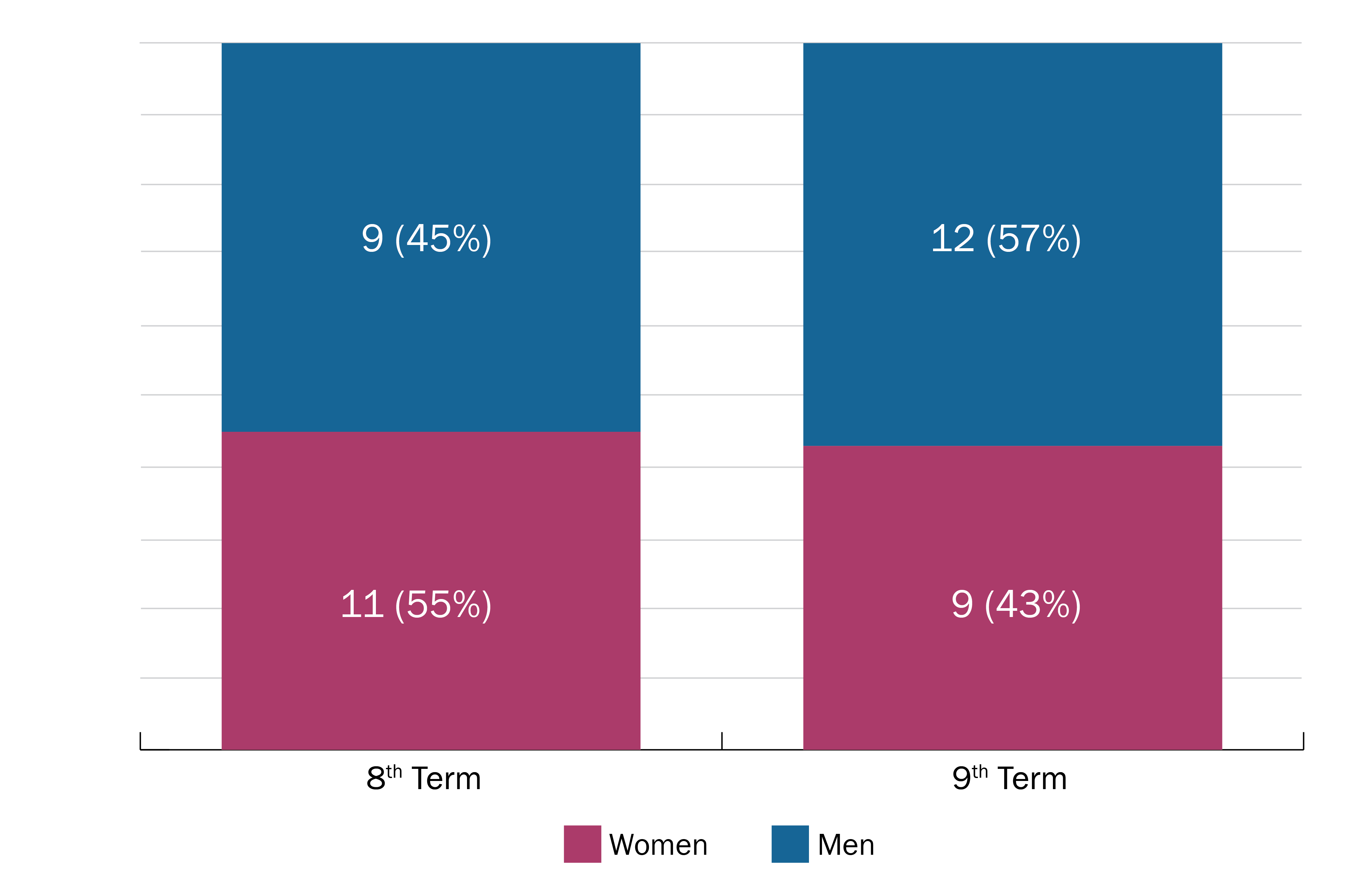

While there was in increase with regard to women MEPs between 2014 and 2021, the share of women committee chairs in the same period dropped significantly, from 55% to 43%. (Figure 8.) But, while women are less represented among the committee chairs than before, at this level they are slightly overrepresented compared to the level of women as MEPs.

Figure 8. Proportion of Men and Women Committee Chairs.

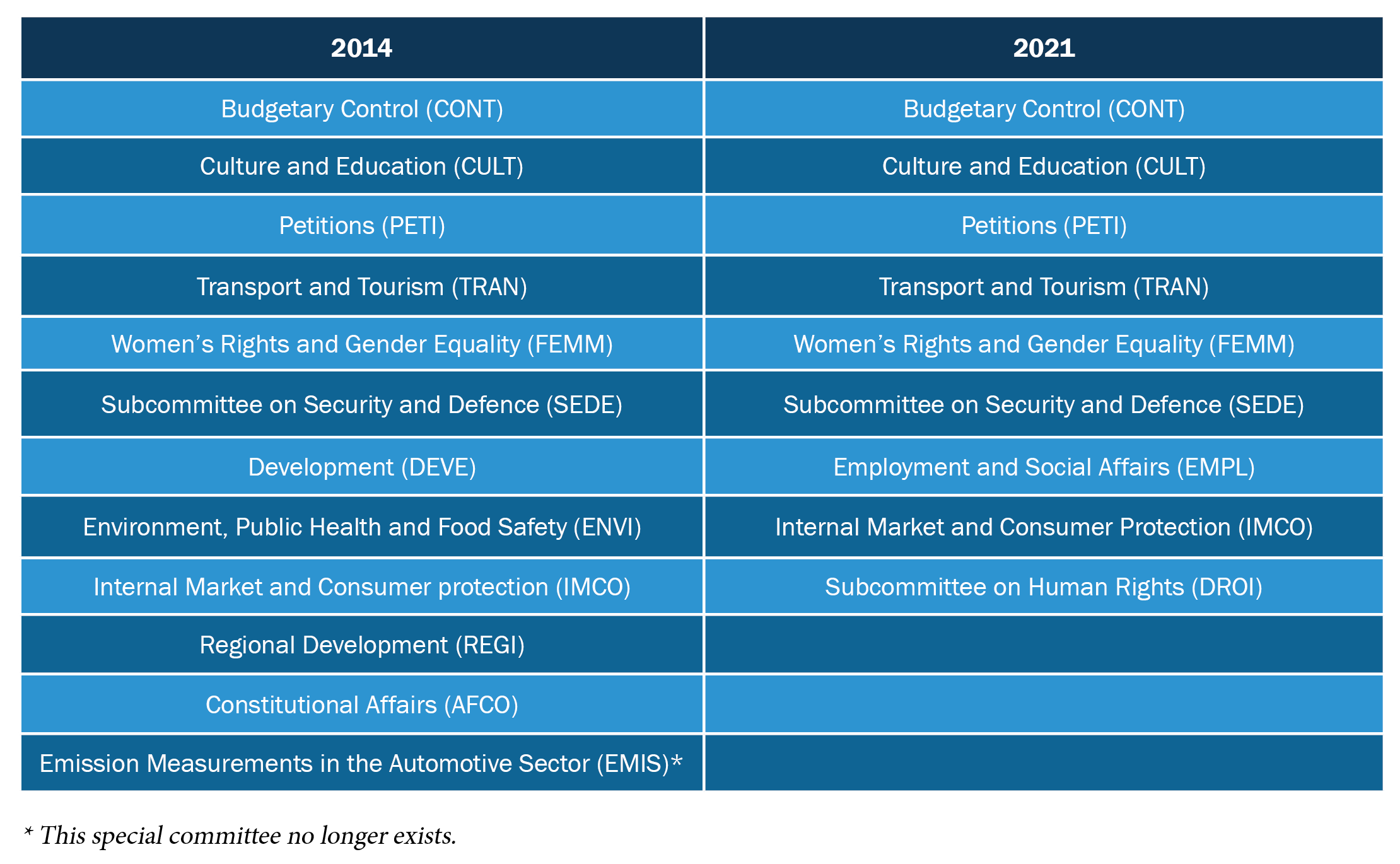

No clear trend can be distinguished in terms of which committees are chaired by women, with a mix between monetary, social, and defense policy areas. (See Table 2.) There were not many major changes between the previous and current terms, with women retaining the chairs of five committees and one subcommittee. Women lost the chair of committees relating to the environment and development, such as ENVI, DEVE, and REGI. The change in the chair of DEVE is noteworthy due to the significant increase in the number of women on the committee. Half of the committees with a woman chair in 2014 also had one in 2021.

Table 2. Committee and Subcommittees Chaired by Women, 2014 and 2021.

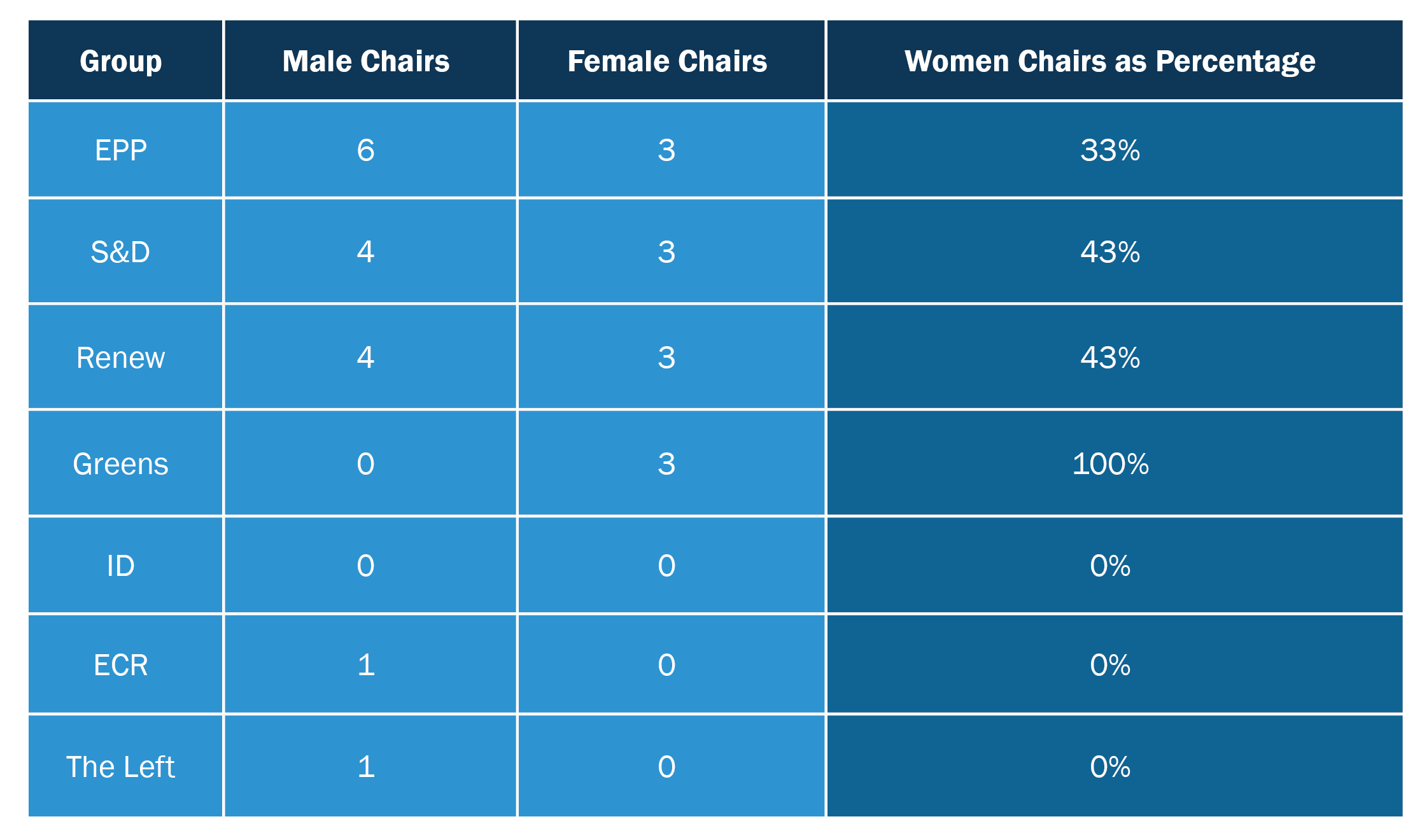

There is a similar picture of gender imbalance in terms of political groups. (See Table 3.) Among those groups with more than one committee chair, The Greens stand out for having only women committee chairs. The political group nearest to gender parity is S&D, with 43% of its chairs being women, a figure also closely reflecting the gender composition of the group in the parliament. One-third of the EPP chairs are women (the figure for Renew Europe was originally 20%, suggesting that the group has not had a policy in place to ensure proportionality at this level). This means the EPP group has a close match with its overall gender composition while Renew Europe, even with the addition of another female chair, does not. Until May 2021, Renew Europe had the most unequal representation, having half the female representation among its chairs as they should have if proportionality had been considered. This changed, however, when Slovakian MEP Lucia Nicholsonová left the ECR group to join Renew.10

Table 3. Men and Women Chairs by Political Group, 2021.

Behind the Numbers

While the European Parliament has seen a steady increase in the proportion of female MEPs over the years, from 16% in 1979 to 39.5% in 2021, this is far from the whole picture when it comes to women’s representation. When looking behind the numbers, important nuances become visible.

Although there are more women MEPs in the parliament today than in the previous term, the number of women chairing committees has decreased from 11 to 9 while the number of male chairs rose from 9 to 12. An overall increase in women in the parliament therefore does not automatically mean a consequent increase in the proportion of women chairs, which raises questions relating to the impact of greater representation on women’s influence. It will be interesting to observe if this pattern continues, or if it changes with the coming rotation in early 2022.

The rules on the gender composition of a committee’s leadership state that at least one of the chair and vice-chairs (thus, at least 20%) should be from the other gender than the majority in the committee. The same could in theory be applied to overall committee composition but this is not the case. One possible reason is that the appointment of female committee chairs and vice-chairs by a political group diverts attention from the gender imbalance in that committee. This could apply, for example, to the parliament’s fourth most male-dominated committee, SEDE, which has a committee leadership that is predominantly female (see below).

A mix of external and internal factors is at play when it comes to questions of gender balance in the European Parliament. The external factors shape its overall composition and there is little it could do to address them.

First, how well represented women are in the parliament varies across member state. Only a few countries have complete or nearly equal gender balance in their representation in the parliament. They raise the average, since other member states have only few—or in one case no—women among their MEPs. In this regard, a significant geographical divide can be identified.

Second, the distribution of women in the parliament across political groups is also skewed. Some groups have higher numbers of women, although none reaches parity, while others have fewer. To a considerable extent, this shows a left-right divide, with political groups located at the right end of the political spectrum having a lower proportion of women. However, the only two women to have been president of the European Parliament have been from the conservative EPP and the liberal ALDE (now Renew Europe) groups.

The internal factors relate to the workings of the European Parliament, its composition, and the political groups. Therefore, the parliament, and in many cases individual political groups, could address and remedy them if they decided to do so.

While women make up almost four out of every ten MEPs, they are distributed unevenly among the different committees and subcommittees. In several of the committees, women are underrepresented relative to their numbers in the parliament, making up less than 39.5% of the committee members, and in others they are overrepresented.

While women make up almost four out of every ten MEPs, they are distributed unevenly among the different committees and subcommittees. In several of the committees, women are underrepresented relative to their numbers in the parliament, making up less than 39.5% of the committee members, and in others they are overrepresented. While in some cases this overrepresentation or underrepresentation is minor, in others the composition of a committee is severely skewed. This can happen with a significant overrepresentation of men, as in the case of the AFCO committee, with 85% men, or of women, as in the FEMM committee with 89% women.

Committees such as AFET, SEDE, and ECON have a significant overrepresentation of men, while FEMM, DEVE, and EMPL have one of women. Looking at the committee composition in the previous parliament reveals that, to a considerable extent, the problem is not new. Committees like FEMM and EMPL also had significant female overrepresentation, and this has grown. For example, the female membership of FEMM has gone from 70% to 89% and EMPL from 47% to 54%. The DEVE committee, on the other hand, has gone from women being underrepresented (20%), to being overrepresented (53%). This clearly shows that not only change occurs, but that it can also be significant. While each political party has the possibility to bring a gendered lens to committee composition, not doing so could mean that such a lens is not applied coherently.

The second internal factor is women’s leadership within the parliament, referring here to committee chairs and vice-chairs.17 While the parliament has seen an increase in women MEPs, there are fewer committees chaired by women today. In the previous parliament, women accounted for 55% of chairs, making them overrepresented in absolute terms and relative to women’s share of MEPs. In the current parliament, however, the proportion of women committee chairs is almost equal to that of women in the parliament.

Today, several of the women chairs head committees dominated by men. This is, for instance, the case for the CONT and ECON committees that have 23% and 24% of women members, respectively. The traditionally male-dominated SEDE committee has not only its second woman chair in a row, but also two women vice-chairs out four. This means that, with about a quarter of its members being women, it has a leadership that is 60% female. What is clear from these observations is that no clear pattern is identifiable. Women chair some male-dominated committees, but they also chair committees with a disproportionately high number of women members.

Questions that remain to be answered relate to the reasons behind the unequal distribution of male and female MEPs in the different committees. Is it because of clear differences in choices or priorities made by male and female MEPs, or is it also influenced by the priorities of the political groups? Since MEPs are not necessarily members of all the committees they might have aspired to, it could be a combination of the two. The reasons behind the drop the number of female committee chairs warrants further investigation, yet the secret nature in which many of the appointment decisions are taken makes this a difficult task.

Another important question is why more is not done to address the poor gender balance in committees. The European Parliament has had gender mainstreaming on its agenda in various forms for many years, yet this does not seem to have led political groups to ensure policies are in place to avoid the unbalanced composition of committees. The same goes for the leaderships of the committees, an area where policies should be easy to put in place, especially by the larger groups.

All of this paints a picture of a European Parliament where the truth of women’s representation means going beyond the numbers. There are important nuances at play, and significant geographical and political differences makes the issue more complex, but not impossible to change. It will be interesting to see if there is political will to change things, if the existing situation will be reproduced, or if certain issues will be further exacerbated in the midterm rotation in the parliament due in early 2022.

Conclusion

While there has been an increase in the proportion of women MEPs between the previous and current European Parliament, there has been a decrease in the proportion of female committee chairs. Women used to make up 55% of chairs, an overrepresentation given they made up 37% of MEPs; now a 41% proportion of chairs is more in line with a proportion of MEPs at 39.5%.

As the proportion of female MEPs has increased, the distribution of men and women in committees remained relatively unchanged, albeit with significant differences, with committees such as AFET remaining predominantly made up of men, others such as DEVE widely increasing the proportion of women, and others such as FEMM increasing the overrepresentation of women. As noted, several of the committees chaired by women have a disproportionate number of men, as in the case of the ECON committee and the SEDE subcommittee.

In conclusion, the data presented in this paper raises several questions for further analysis. These include:

- To which degree does gender play a role when political groups distribute committee positions among their members?

- What role does geography have in the gender distribution of the various political groups?

- What are the factors determining committees’ gender distribution?

- Who could be the driving force to make the European Parliament a truly gender-balanced representative body? Should the onus be on the institution itself or should this effort come from the political groups?

- How often is the discussion on gender on the agenda of political groups? Is this something that can be debated openly, or does it need to be framed in a particular way?

- Is the underrepresentation of women in committees related to their subject area, as is sometimes the case in other institutions?

The question also remains as to how the European Parliament will achieve its own gender mainstreaming, either in the current term or the next. As its research service has concluded, despite good progress in gender mainstreaming over the past years, its work in this regard remains far from finished.11

- 1Rosamund Shreeves and Nora Hahnkamper-Vandenbulcke, Gender mainstreaming in the European Parliament: State of play, European Parliamentary Research Service, September 2021. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2021/694216/EPRS_STU(2021)694216_EN.pdf

- 2European Parliament, Resolution on Gender Mainstreaming in the work of the European Parliament, March 8, 2015.

- 3European Union, Gender Equality Strategy, March 5, 2020. https://ec.europa.eu/info/policies/justice-and-fundamental-rights/gender-equality/gender-equality-strategy_en

- 4European Parliament, Gender equality: Parliament strives to be frontrunner among EU Institutions, April 30, 2021. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/en/press-room/20210430IPR03214/gender-equality-parliament-strives-to-be-frontrunner-among-eu-institutions

- 5Shreeves and Hahnkamper-Vandenbulcke, Gender mainstreaming in the European Parliament. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2021/694216/EPRS_STU(2021)694216_EN.pdf

- 6European Parliament, MEPs, Full list. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/meps/en/full-list/all

- 7European Parliament, MEPs’ gender balance by country: 2019, July 8, 2019. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/election-results-2019/en/mep-gender-balance/2019-2024/

- 8Shreeves and Hahnkamper-Vandenbulcke, Gender mainstreaming in the European Parliament. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2021/694216/EPRS_STU(2021)694216_EN.pdf

- 9Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Denmark, Income and gender equality in Denmark. https://denmark.dk/society-and-business/equality

- 10Agence Europe, “MEP Lucia Nicholsonová leaves ECR group to join Renew Europe”, May 25, 2021. https://agenceurope.eu/en/bulletin/article/12726/31

- 11Shreeves and Hahnkamper-Vandenbulcke, Gender mainstreaming in the European Parliament. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2021/694216/EPRS_STU(2021)694216_EN.pdf

Appendix

Expand AllCommittee Abbreviations

AFCO: Constitutional Affairs Committee

AFET: Foreign Affairs Committee

AGRI: Agriculture and Rural Development

AIDA: Artificial Intelligence in a Digital Age

ANIT: Protection of Animals during Transport

BECA: Beating Cancer

BUDG: Budgets

CONT: Budgetary Control

CULT: Culture and Education

DEVE: Development

DROI: Human Rights

ECON: Economic and Monetary Affairs

EMPL: Employment and Social Affairs

ENVI: Environment, Public Health and Food Safety

FEMM: Women’s Rights and Gender Equality

FISC: Tax Matters

IMCO: Internal Market and Consumer Protection

INGE: Foreign Interference in all Democratic Processes in the European Union, including Disinformation

INTA: International Trade

ITRE: Industry, Research and Energy

JURI: Legal Affairs

LIBE: Civil Liberties, Justice and Home Affairs

PECH: Fisheries

PETI: Petitions

REGI: Regional Development

SEDE: Security and Defence

TRAN: Transport and Tourism