The Place of Roma Women and Girls in Hungary’s Social Integration Strategies: A Gender Analysis

About the Author

Marina Csikós is a gender researcher and Roma feminist from Hungary. Over the past four years, she has worked on several initiatives tackling intersectional discrimination against marginalized groups in Europe. She holds an MA in critical gender studies from the Central European University, where she focused her research on anti-racism, feminist knowledge production, and intersectionality. She joined the Phiren Amenca International Network in Brussels after completing a traineeship at the European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights. She has been involved in the Romani movement for ten years and engaged in different activities with several Roma and non-Roma civil society organizations and institutions in Europe.

Summary

While national Roma inclusion strategies play a key role in improving the situation of the Roma population in the European Union’s member states, Roma women and girls still lack fundamental rights—such as access to quality education and employment, to quality health care, or to justice—in most European countries, including Hungary.

In 2011, the European Commission, acknowledging the unacceptable situation of the Roma and its responsibility to improve it, issued an EU Framework for National Roma Integration Strategies up to 2020. In this document, it requested all member states to develop and implement targeted strategies, as well as to devote sufficient resources to promote Roma integration in four priority areas: health, housing, education, and employment.

The first Hungarian National Social Integration Strategy (HNSIS) adopted in 2011 tackled the social exclusion of Roma people in the context of a wider national social integration strategy dealing with extreme poverty, child poverty, and specific issues that concern the Roma population. It also set the horizontal objective of “reducing the educational and labor market disadvantages” of Roma and considered the needs of Roma women in most of the priority areas of the EU Framework for Roma Strategies.

A gender analysis of the HNSIS leads to three main conclusions. First, there was a lack of awareness and practical implementation of intersectionality in the strategy. Second, there was a strong tendency to blame Roma traditions and culture for the disadvantaged situation of Roma women and girls, which is very much linked to the anti-gypsyism in Hungarian society. Third, the evidence of homophobia, racism, and sexism in the HNSIS and its measure were serious concerns if the state wanted to improve the situation of Roma women and girls.

In 2020, the European Commission adopted a new framework for the following ten years—A Union of Equality: EU Roma Strategic Framework for Equality, Inclusion and Participation. One of the improvements in the new strategy is that an intersectional approach is recognized as the only way to effectively tackle discrimination. It also places more emphasis on political participation.

In September 2021, after some delay, Hungary adopted its Social Integration Strategy 2020–2030. While the new EU strategic framework includes many novelties, the new Hungarian strategy does not improve the previous one much. The main goal remains to tackle poverty and to reduce the disadvantages faced by poor people, while it is also stated that there will be more emphasis on climate change, mental health, digitalization, and cross-border cooperation. While all these areas are very important, fighting anti-gypsyism and increasing political and civic participation receive less attention in the new strategy, regardless of the EU’s recommendations.

In order for Hungary’s current Social Integration Strategy to have positive effects regarding the situation of Roma women and girls, there should be major changes to it. Using intersectionality as a baseline for the strategy must be essential, along with specifically addressing the needs of marginalized Roma women and girls such as trans women, lesbian women, and girls living in rural areas. Moreover, as the European Commission also identified in its framework, combating anti-gypsyism, political empowerment should be among the priority areas as well.

Introduction

Roma women experiencing forced sterilization, worrying rates of school dropouts among Roma girls, lack of access to basic hygiene products, violence against Roma women sex workers, dehumanization of Roma trans women, and discrimination in the labor market are just some of the issues Roma women and girls experience on a daily basis in Hungary and elsewhere in Europe. While national Roma strategies play a key role in improving the situation of the Roma population in the European Union’s member states, Roma women and girls still lack fundamental rights in most European countries, including Hungary. These worrying facts inform the analysis in this paper of Hungary’s social integration strategies from a gender-equality point of view, focusing on Roma women and girls. In 2011, the EU member states committed themselves to promoting the urgently needed more efficient social and economic integration of the Roma communities. They aimed to achieve this by creating the EU Framework for National Roma Integration Strategies, which provided a new approach to addressing this problem. The aim was for this framework to be used by national and local decision-makers.1 It was a huge step toward the integration of the Roma, mobilizing the member states to take concrete actions for improving the situation of these neglected citizens.

At the same time, the growing demand for gender equality and for creating a more equal Europe for all women has also gained more attention, leading to more actions being taken in that regard at the EU and national levels. While Roma women and women from other marginalized groups have not been equally included alongside white women in the gender equality discussions, the aim to improve the situation of Roma women and girls has been receiving more attention in the EU. Some member states have made relatively good progress in including a gender-sensitive approach into their national Roma integration strategies.

It is important to look at how women and girls are present in Roma integration strategies for two major reasons. First, as mentioned above, they face multiple forms of economic, political, and social discrimination. Therefore, any national strategy that aims to improve the situation of the marginalized Roma communities must address the issues women and girls face. Second, the still unequal participation of women in decision-making processes leads to an insufficient gender-sensitive perspective in policy. Therefore, the development of policies and programs for women (particularly minority women) often do not fully reflect their needs and experiences. Having policy documents that are written by minority women and about minority women is a necessary step forward to better carry out integration policies and strategies.

Hungary is a good case study for how gender has been taken into account in a national Roma integration strategy in the EU. It has one of the largest Roma populations in the EU, with Roma people having lived in and contributed to the country for centuries. In the past 12 years, Hungary has also become one of the most conservative and anti-Roma countries in Europe—paradoxically as it (along with many other EU member states) has expressed the commitment to improving the wellbeing of its Roma population in all fields of life. Beside the increase of anti-gypsyism in the country, anti-gender sentiments have been also appeared more and more frequently in the past decade. This has been reflected in the banning of gender studies and in anti-LGBTQA+ policies and measures, among other developments, since 2010, when the governing Fidesz party started to turn Hungary into an increasingly fascist state. This has happened as the same time as gender equality has become a top priority to the EU.

In line with the EU Framework for Roma integration, Hungary adopted a national Roma integration strategy in 2011, which was implemented up to 2020. It adopted a second such strategy in 2021 to be implemented from 2022 to 2030. This paper examines whether and how the needs and experiences of Roma women and girls have been addressed in the two strategies. It looks at the key areas (education, employment, and health) that the strategies emphasize with regard to Roma women and girls and offers a gender analysis of the related contents and measures. The paper also discusses the Roma Civil Monitor, which is one of the most powerful tools of Roma and pro-Roma civil society organizations (CSOs) to take part in monitoring of the implementation of the national Roma strategies throughout the EU. The paper concludes by offer policy recommendations to improve the situation of Roma women and girls through Hungary’s Roma integration strategy.

Roma Women in the EU and Hungary

Sexism and patriarchal oppression, from which women and LGBTQA+ people suffer the most, remains a common problem across Europe. And, as women still suffer from the negative and violent consequences of sexism, the situation of women of color, and particularly Roma women, is even worse and more desperate. Roma women are not only the victims of gendered stereotypes, violence, and oppression caused by sexism, but also of anti-gypsyism.

Even though gender equality has been one of the objectives of the European Union since 1957, women are still far from equal to men in most of its member states. The EU has made efforts to close the gender gap. Article 23 of its Charter of Fundamental Rights requires that equality between women and men be ensured in all areas. In 2017, the Council of the European Union sent a strong political message to all member states when it signed the Istanbul Convention, which aims to prevent and combat violence and domestic violence against women, and it called for them to sign it. Despite such legal and political efforts, a stocktaking EU report in 2018 concluded that equality between women and men was being achieved too slowly or, in some cases, was even getting worse.1 An intersectional approach is necessary in discussing the situation and lived experiences of Roma women and girls. For example, the European Institute for Gender Equality defines intersectionality as an “analytical tool for studying, understanding and responding to the ways in which sex and gender intersect with other personal characteristics/identities, and how these intersections contribute to unique experiences of discrimination.”2 Using this approach means taking into consideration how different forms of oppressions—such as sexism, racism, ageism, or homophobia—independently or simultaneously affect the lives of those who are affected by them. Intersectionality does not only help to understand the power relations when different people with different identities interact with each other; it also provides a methodological framework to map out the situation of different groups of people. The EU Agency for Fundamental Rights (FRA) followed an intersectional approach in producing in 2019 its Second European Union Minorities and Discrimination Survey, which focused on the experiences of Roma women in nine member states.4, 5 The report highlights three important areas of life: education, employment, and health.

Education

Article 14 of the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights states that everyone has the right to equal education regardless of, among other things, their race or religion. Education was given a prominent place in the EU framework for Roma integration and later in the national Roma strategies. When it comes to the Roma, education is extremely important for increasing social and economic mobility. Roma boys and girls significantly suffer from a lack of access to the same quality of education as those from the majority populations. Although the share of Roma girls attending primary school is usually higher than that of Roma boys in the nine countries, it is still below that of the majority populations. In the case of the Roma, this share is 81 percent on average in the surveyed countries while in Hungary it is 98 percent. For Roma girls, the problem comes later during their education, sometimes when they reach their teenage years. The FRA report shows that in the nine countries 66 percent of Roma boys between the ages of 16 and 24 neither attend secondary school nor get any form of employment, but the situation is worse for Roma girls at 71 percent.

Lack of information about how to live a healthy and protected sexual life, imposed gendered roles, and early motherhood are just some factors for the lower participation of Roma girls in education. In their case, gendered oppression is compounded by racism, which makes a dangerous combination. Although Roma girls enter the education system, they do not remain in it due to different factors. These relate, among other things, to systematic discrimination, school segregation, bad quality of education, and disadvantaged economic backgrounds. The European Rights Center has also found that Roma pupils are heavily overrepresented in Hungary’s special schools, mostly due to systematic racism.6 These are schools for students with special educational needs, such as those with disabilities, with learning and behavioral difficulties, and with socioeconomic disadvantages. In Hungary and in several other European countries, Roma students for many years have been medically misdiagnosed (due to anti-gypsyism, language barriers, and cultural indifference, among other things) and sent to such special schools even when it was not necessary. In general, Hungary’s public education system is highly responsible for the ongoing inequalities experienced by Roma children, especially girls.7

Employment

There is a strong relationship between educational opportunities and employment. If a person does not have access to quality education, dropped out of school, or studied in segregated classes, most probably they will have less chance of getting a well-paid, secure job. Since Roma girls are more likely drop out of school than any other students, the issue of unemployment and unhealthy circumstances at work are common for them when they step into the labor market. While across the nine countries, according to the 2019 FRA survey, 34 percent of Roma men were employed, only 16 percent of Roma women were. This shows the desperate reality of Roma women in Europe when it comes to employment. The low percentage of working Roma women can be explained by many interrelated issues. Education in particular has a lot to do with a young woman’s opportunities in the labor market. The education lacking quality that most of Roma girls receive in schools, school segregation, and lack of cultural sensitivity and diversity, among other factors all affect a young Roma woman’s career opportunity. Starting with the difficulty in finding jobs, Roma women in Hungary and the other countries also commonly suffer from excessive commuting to the workplace, being disrespected and discriminated due to their gender and ethnicity, working in unhealthy conditions, and receiving lower wages than their male peers for the same job.

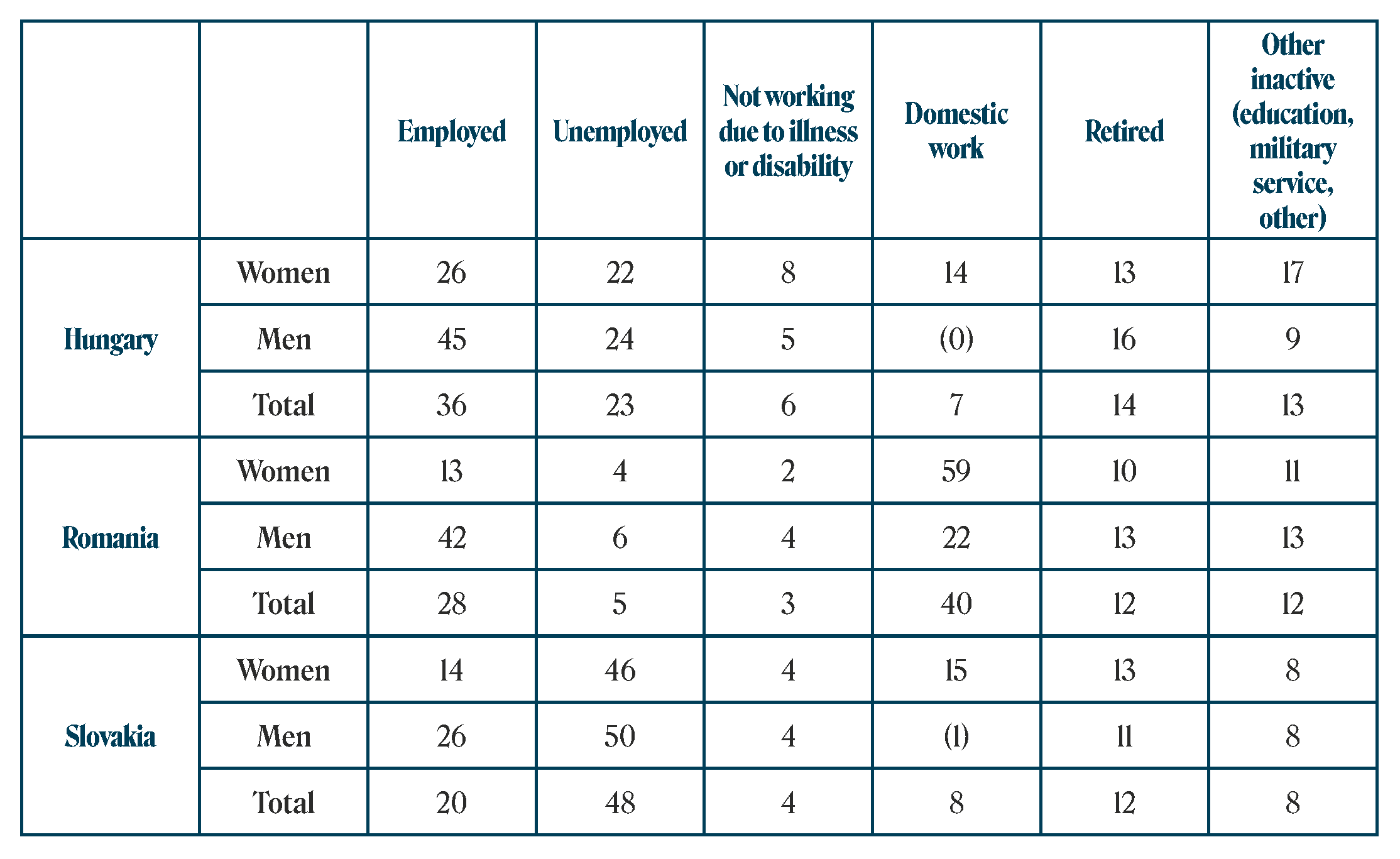

Table 1. Current main activity, all persons in Roma households surveyed aged 16 years or over (percent)

Notes: Out of all persons aged 16 years or over in Roma households (n=22,097); weighted results. Results based on a small number of responses are statistically less reliable. Thus, results based on 20 to 49 unweighted observations in a group total or based on cells with fewer than 20 unweighted observations are noted in parentheses.

Source: Fundamental Rights Agency, Second European Union Minorities and Discrimination Survey – Roma Women in Nine EU Member States, 2019.

Health

The 2019 FRA report shows that in Hungary Roma women feel more limited in their daily activities because of health issues than their non-Roma peers (29.3 percent and 23 percent respectively). The life expectancy of Roma women is approximately ten years less than that of non-Roma women in the country.8 An unhealthy lifestyle and diet, a high incidence of smoking, lack of access to quality health care, lack of awareness about healthy diet, forced sterilization, and—above all—discrimination based on their origin are just some of the main reasons for the bad health conditions of Roma women and girls. Although the EU member states have invested huge financial resources into Roma “health mediators”—members of the community who are trained to liaise between it and the and mainstream health care institutions—most Roma did not use the services of these mediators, according to the 2019 FRA survey.

Growing EU Attention

Since December 2007, according to several conclusions of the Council of the European Union, the European Commission found that there are already powerful EU frameworks of policy coordination as well as financial and legislative tools available for the member states to improve the situation of the Roma. However, the council has also stated that more could be done. It has affirmed that there is a joint responsibility of all the member states to take action and address the challenge of Roma integration, and to create an inclusive society. From 2009, the member states shifted their approaches toward the Roma. From analyzing the problems faced by the community, they started to work on how existing instruments could be more effective and how the situation of the Roma could be improved through employment, education, health, cultural, youth, and social integration policies. Beside enforcing and developing further EU legislation in the areas of freedom of movement, data protection, non-discrimination, and anti-racism, the European Commission wanted to make sure that a Roma-specific perspective was included in the work of already existing structures, such as the Fundamental Rights Agency and the European Network of Equality Bodies (EQUINET). Moreover, different non-discrimination and Roma-specific trainings were carried out for legal practitioners working at the European Commission.

In 2009, a European Platform for Roma integration was created, which consisted of several CSOs, member-state governments, and international and EU institutions working on Roma inclusion. Due to the increased commitment of some of the member states and EU institutions, there has been some improvement in the situation of the Roma Europe-wide.9 Many of these were due to the EU Structural Funds, particularly the European Social Fund and European Fund for Regional Development. The effectiveness of the European Social Fund with regard to Roma integration lay in supporting the member states in how they can use EU funding in the best ways and in monitoring and evaluating Roma-specific projects. To enhance the knowledge about what are effective tools for Roma integration, the European Commission also implemented a €5 million pilot project from 2010 to 2012, which was initiated by the European Parliament. The project addressed Roma self-employment and early-childhood education through micro-credit, and it also raised public awareness in areas with a high Roma population.10

The EU Roma Integration Framework, 2011–2020

In 2011, the European Commission, acknowledging the unacceptable situation of the Roma and its responsibility to improve it, issued an EU Framework for National Roma Integration Strategies up to 2020. In this document, the European Commission requested all member states to develop and implement targeted strategies, as well as to devote sufficient resources to promote Roma integration in four priority area: health, housing, education, and employment.

This document stated that it was the responsibility of the EU and its member states to improve the situation of the Roma since they have the political, financial, and structural resources to do so. Roma people, as citizens of member states, should enjoy the same rights as non-Roma ones. However, the reality is that Roma people do not have full access to fundamental rights and face serious obstacles in this regard. Even though the EU Framework acknowledged that the member states should make sure that Roma enjoy the same rights as others, it lacked a discussion about what the specific responsibilities the member states have. Moreover, the document is completely silent about racism and how it has become an integral part of European structures, including the European Union.

Rather, the EU Framework presented a patronizing approach and implied that the Roma were not able to solve “the Roma issue” by themselves, which is why they needed the help of the EU. This approach is not unique: the EU used very similar ones with regard to gender, LGBTQA+, and people living with disabilities, for example.

The Roma are economically very important to Europe because they represent a young population that struggles with unacceptable gaps when it comes to education and employment. Helping them to close these gaps and to make their situation better will be not only profitable to the Roma themselves but to the EU and its member states as well. This approach somewhat also shaped the way Roma integration was addressed up to 2020. But treating integration as a purely economic issue instead of a more complex one is quite problematic as Roma people face systematic discrimination at all levels of their lives. The economic dimension is an integral part of the matter but clearly not the only one. Education, health, decision-making, housing, and youth issues should be also effectively targeted by integration measures. Even though the EU Framework stated that the Roma’s bad educational, employment, housing, and health conditions were mainly caused by ethnic-based discrimination, it did not explain or offer strategies for how racial discrimination should be tackled by the EU and the member states. The EU Framework implied that all the problems of the Roma would be solved if their economic situation were to be improved through access to education, employment, housing, and health care.

After presenting the main principles and approach to Roma integration, the EU Framework discussed national Roma integration strategies. Even though this part should have been the most detailed and concrete one, it in fact contained not much information. The EU Framework addressed this under six points:

- The member states should set up national Roma integration goals that should reflect on the four key areas of life where the situation of the Roma should be improved: education, employment, housing, and health.

- The most disadvantaged areas, segregated neighborhoods, and micro-regions should be targeted by the integration measures.

- The member states should allocate sufficient funding from their national budget, to be complemented by different EU sources of funding. The member states should set up an efficient monitoring scheme to evaluate progress and achievements.

- Roma civil society, regional, and local organizations and institutions should be involved in the design, implementation, and monitoring of the national integration strategies.

- The member states were advised to set up national Roma contact points that would be responsible at several stages of the strategies.

Hungary's First Integration Strategy

The first Hungarian National Social Integration Strategy (HNSIS) adopted in 2011 tackled the social exclusion of Roma people in the context of a wider national social integration strategy dealing with extreme poverty, child poverty, and specific issues that concern the Roma population. The HNSIS identified a horizontal objective targeted at “reducing the educational and labor market disadvantages” of Roma and considered the needs of Roma women in most of the policy areas that being discussed. A specific part of the HNSIS was dedicated to the situation of Roma girls and women with respect to their disadvantages in education, access to employment, and health.

Education

First, the HNSIS focused on improving the situation of Roma girls and women through developing an inclusive school environment that supports integrated education and that provides an education attempting to break segregation and disadvantages. It highlighted that early school-leaving is one of the main causes for low levels of education among Roma women. While describing the situation of Roma girls, the HNSIS made a strong connection between particular gendered roles within the Roma community and the quality of educational opportunities. It argued that gendered factors such as women taking care of the whole household, raising children, and being under pressure to marry are common in Roma culture and traditions. There was no mention, though, of how racism, anti-gypsyism, and bad economic circumstances lead to gendered roles, which makes the argument weak and unreliable. This approach does not only ignore how anti-gypsyism and its negative effects reinforce certain gender roles in different communities; it also ignores the fact that there are many Roma girls and women who do not want to live in heterosexual relationships and resist gendered roles. The HNSIS was intended to improve the educational situation of Roma girls and women through developing pedagogical processes that are better adjusted to their needs as students, focusing on desegregation and integrated schools, and creating mainstream policies that reflects on the specific needs of the Roma. However, there was no indication in it of how to tackle issues that leads to low educational performance, such as systematic oppression and challenging patriarchal structures (not only in Roma communities) among other things.

Employment

When it comes to the employment situation of Roma women, the HNSIS put a special emphasis on providing equality programs and measures to close the gap between Roma women and the rest of the Hungarian population. Here too, it stressed that cultural factors can negatively affect the employment rates of Roma women. But it made no reference to any scientific literature on these cultural factors, a signal that this was a weak point in the strategy. However, what the strategy did not really discuss is that, due to racism, Roma women are less likely get hired even if they have the same qualifications as non-Roma ones, face microaggressions in the workplace with an obvious negative effect on their mental health, and get fired more than their non-Roma colleagues, among other things. The strategy seemingly did not intend to address how different factors, such as racism and mental and physical health, were intertwined with each other, which would be crucial for improving the Roma’s situation in Hungary. On the positive side, the strategy identified the necessity to invest in Roma women with young children and to support their reintegration into the labor market. For this, “integration support” would be provided by the state adult education institutions to those who participate in labor-market training courses.

Health

The HNSIS presented and discussed data on Roma women’s health conditions. The planned measures to improve these targeted mainly pregnancy, since according to the document, teenage pregnancy was still an issue among Roma girls. Roma girls would be targeted by campaigns about conscious family planning and how to carry out a healthy pregnancy. Beside these campaigns, special attention would be given to families with young children to have adequate access to health care and to contraceptive options. The HNSIS seemed to see contraception as an important element of the health of Roma women, stating that “For the purpose of increasing the effectiveness of these devices, the individuals concerned should in every instance be given advice on family planning and contraception.” In the Hungarian and Central and Eastern European contexts, however, how public institutions and the state handle the question of contraception when it comes to Roma women is extremely complicated and sensitive. The region has experienced several cases of forced sterilization of Roma women not only in the past but nowadays as well. The European Roma Rights Center has worked on several cases of Hungarian women being victims of forced sterilization due to their Roma origin.11 There was no mention of this matter in the HNSIS, which shows the lack of an intersectional perspective and contextualization of the topic.

Implementation of the First Strategy

The Roma Civil Monitor (RCM)—or “Capacity building for Roma civil society and strengthening its involvement in the monitoring of national Roma integration strategies”—was a pilot project initiated by the European Parliament and managed by the European Commission that ran from March 2017 until March 2020.12 The objective was to contribute to strengthening the monitoring mechanisms of the implementation of the national Roma integration strategies through systematic civil society monitoring. One important element of the civil society monitoring was that it had independent status. The project aimed to enhance civil society monitoring in two key ways: by developing the policy monitoring capacities of civil society actors and by supporting the preparation of high-quality, comprehensive annual monitoring reports. It was implemented with the active participation of about 90 CSOs from 27 member states (Malta was not part of the project as it has no Roma community.)

Over the three years of monitoring, the members of the Hungarian Roma Civil Monitor produced three reports on the implementation by the state of the HNSIS for improving the situation of Roma girls and women in Hungary. These reports show that there were two major programs that targeted Roma women and girls countrywide. The first—Nő az Esély (The Opportunity Is Growing)—aimed to train 1,000 Roma women in social services and health care and to provide employment opportunities in the public sector for them after completing the training. According to the RCM, this program was highly promoted and claimed to be one of the most successful when it comes to Roma women. However, only about 400–500 out of the 1,000 women involved got jobs after completing the training to be health care workers and nannies.

The second, larger program—Bari Shej (“Big Girl” in Romani) mostly targeted Roma girls living in disadvantaged areas. Its projects targeted Roma girls aged 10–18 from severely disadvantaged backgrounds who were at risk of dropping out from school for various reasons. The projects aimed to help young Roma girls through their difficulties by offering them various trainings on self-confidence, self-awareness, communication, learning strategies, and mentoring. The program was implemented for 24 months by 89 organizations. To learn about it, the RCM interviewed several Roma girls in the town of Buják. According to the RCM, the girls could not openly talk about certain topics that are often treated as taboos in the Roma community, such as sexuality and family planning. The RCM also pointed that the program failed to take into account the different difficulties Roma women might face in their lives, such as financial difficulties with regard to travelling, material circumstances, cultural elements, and so on. Besides critically reflecting on the concepts and outcomes of the programs, the RCM also identified crucial issues of favoritism, lack of transparency, and lack of consultation with Roma CSOs.

It should be noted that the Hungarian RCM itself could be improved in terms of gender sensitivity. Even though it paid attention to the measures related to Roma women and girls, its third country report contained almost no reference to them. Moreover, the RCM coalition members included neither Roma women nor LGBTQA+ organizations. The lack of inputs of knowledge from Roma experts and of grassroots experience on these issues were obstacles to producing gender-aware and gender-reflective civil monitoring reports.

Three main conclusions can be drawn from the HNSIS 2011–2020. First, there was a lack of awareness and practical implementation of intersectionality in it. The strategy pointed out several important issues that Roma girls and women face in Hungary, but discrimination based on race, sexuality, disability, or age were not taken into account—neither in discussing the situation of Roma women and girls, nor in the targeted measures.

Second, there was a strong tendency to blame Roma culture and traditions for problems that are more complex than this approach suggests. At several points, the HNSIS mentioned Roma culture as the source of the disadvantaged position of Roma women and girls. Such false assumptions with no scientific or scholarly support reinforce anti-gypsyism in Hungarian society and maintain systematic oppression that worsens the lives of Roma women and girls.

Third, the evidence of homophobia, racism, and sexism in the HNSIS and its measure are serious concerns if the state wanted to improve the situation of Roma women and girls. While the strategy was intended to work on complex issues such as early marriage, early school-leaving, or improving the mental health of Roma women, it failed to take account the sexual, cultural, and lifestyle diversity that is true not only for Roma girls and women but also for society as a whole. For example, Roma LGBTQA+ people were not mentioned in the HNSIS, even though it is well known that they face discrimination not only due to their Roma origin and gender identity but also due to their LGBTQA+ identity. Therefore, leaving such huge groups of people out of any kind of integration policies and measures, not only for the Roma, was a serious concern and extremely oppressive.

The EU Roma Integration Strategic Framework for 2020–2030

Nine years after the publication of the EU Strategic Framework for Roma Integration and after the end of the first implementation period of the national Roma strategies, the European Commission adopted in 2020 a new framework for the following ten years.13 This title suggests that the EU’s approaches and objectives have shifted from integration to political participation and equality. The document states that, while significant improvement has been made in the fields of early childhood education and early school-leaving, there are fields where the situation of the Roma had stagnated or even gotten worse in the previous ten years. These include segregation of Roma pupils in schools, employment, segregated housing, and many more. Though there is no particular mention of achievements and failures of the first EU Roma strategy when it comes the situation of Roma girls and women from the EU Agency for Fundamental Rights survey’s findings from 2019, there is a clear picture of the differences between them and Roma men and boys. One of the improvements in the new strategy is that an intersectional approach is recognized as the only way to effectively tackle discrimination. The European Commission used the working definition of intersectionality of the European Institute for Gender Equality mentioned above.

Under Objective 5, the European Commission has set the target that by 2030 at least 45 percent of Roma women should be in paid employment. With this target, the aim is to cut by half the gender employment gap between Roma women and men.

Another area, Objective 6 to “Improve Roma health and increase effective equal access to quality health care and social services” focuses on increasing the life expectancy of Roma women and men but makes no specific reference to a goal for women.

A gender perspective or intersectional approach is completely missing from the rest of the objectives. While Roma women and girls are mentioned here and there in the strategic framework, there is a lack of discussion on how intersectionality and gender equality should be addressed in national strategies. The European Commission has attempted to highlight these issues, but how to address them is missing, which makes the new document quite weak when it comes to addressing the special needs of Roma women and girls.

Hungary’s Social Integration Strategy 2020–2030

In September 2021, after some delay, Hungary adopted its Social Integration Strategy 2020–2030. One of the most conspicuous differences with its previous strategy is that the new one does not contain a separate section dedicated to the situation of Roma women and girls. Instead, this issue is more mainstreamed and more or less addressed in different areas, such as early education, employment, youth issues, and identity. While the new EU strategic framework includes many novelties, the new Hungarian strategy starts by stating that its goals have not changed too much and that the planned measures will rely on the already existing structures. The main goal remains to tackle poverty and to reduce the disadvantages poor people (especially poor children) face in Hungary’s poorest regions. The state will put more emphasis on climate change, mental health, digitalization, and cross-border cooperation. While all these areas are very important, fighting anti-gypsyism and increasing political and civic participation receive less attention in the new strategy, regardless of the EU’s recommendations.

The new strategy states that equal access to public services for Roma women remains a horizontal concern. Increasing the access of Roma women to health care and their employment in public institutions also remain as important elements. The strategy has as one main goal to pay particular attention to the prevention of early school-leaving among Roma girls and their further education. Therefore, the state aims to decrease the percentage of those Roma who are “not in employment, education or training” to 30 percent and also to increase the number of disadvantaged people in adult education. The percentage of young Roma who neither study nor work in Hungary is around 41 percent according to the strategy.

Early Childhood

In the section on early-childhood education, the new strategy states that “Disadvantaged women, especially Roma women, need to be encouraged to become foster parents.” This was not mentioned in the first one. According to research from 2011 by the European Rights Center, which the strategy also cites, Roma children in Hungary are overrepresented in the state care system.14 The removal of Roma children from their families due to poverty and related consequences is a major issue in the country. However, instead of acknowledging the fact that racism and systematic oppression has an equal or even much greater role in the removal of Roma children from their homes, the strategy puts the emphasis on the responsibility of Roma parents and their (usually physical) mistreatment of children.

Many times, non-Roma social and public workers discriminate against Roma families and remove children even when the financial situation, parental mistreatment, and living conditions could be improved with the help of social workers, doctors, teachers, and local authorities. Due to systematic racism, Roma parents in hard living conditions are seen as irresponsible and not capable of meeting the needs of their children, when most of the time what they suffer from is the consequences of racism, such as not having proper education and jobs or falling into drug use due to bad mental health. This does not mean that the parents have no responsibility for their misbehavior and poor living conditions. However, the issue is much more complicated than that and one should not ignore the responsibility of the state and the systematic oppression Roma people face.

All of this raise questions as to why and how the state wants to encourage Roma women to become foster parents. Is it because it would like Roma women to raise Roma children since they are overrepresented in state care? And, since many Roma children are removed from their families due to poverty, would the Roma foster mothers come from the middle class or elsewhere? There is also an issue of heteronormativity and homophobia in this approach since it is not legally possible for single and trans women to become foster parents in Hungary; this is only possible for a married couple defined as a “woman and a man” living in heterosexual relationship.

Public Education

When it comes to public education, Hungary’s new integration strategy states that while the average educational level of the population has increased, among the Roma the level is still exceptionally low. In order to improve the educational situation of the Roma, the new strategy adopts a very similar path to that in the previous one. It puts a lot of emphasis on disadvantage compensation, which should take place from kindergarten all the way through university. Disadvantage compensation basically means offering specific training (including free ones), education, financial contribution (stipends etc.) to Roma children and youths that will hopefully compensate for their disadvantageous socioeconomic situation and create better opportunities for them to aspire higher education. The approach that is intended to achieve this is more or less a continuation of the programs and measure that were develop in the past ten years. When it comes to Roma girls, the strategy specifically mentions preventing them from dropping out of school, which is to be targeted through prevention programs and increasing use of the digital infrastructure.

Youth Issues

In the new strategy’s section on youth, early pregnancy receives high attention among the issues disadvantaged young people face in Hungary. According to the Hungarian Central Statistical Office’s micro census, in 2016, the rate of early pregnancies was relatively high among the Roma population at 8.57 percent, compared to 0.7 percent for non-Roma girls. To prevent early pregnancies and dropping out of school among young Roma girls, the strategy states that the Bari Shej program will be continued to tackle these issues. As the Roma Civil Monitor has pointed out, this program was simultaneously useful and problematic. While the Bari Shej program pays special attention to Roma girls who come from disadvantaged background and are more likely to drop out of school due to the bad financial situation of their family, several of its elements have raised some concerns. This includes lack of transparency of the results, favoritism toward certain government-friendly CSOs and churches, and lack of intersectional methodology. Therefore, a close follow-up of this program and its results will be necessary. The new strategy also mentions reaching out to Roma women’s organizations that can help provide role models to young Roma girls. These organizations should also be given the opportunity to offer useful feedback to the organizers of the Bari Shej program.

Employment

When it comes to employment, the new strategy specifically mentions that the number of Roma women who have white-collar jobs is extremely low. In 2019, only 6.9 percent of them had one, while for non-Roma women the share was 44.2 percent. On the other hand, Roma women are overrepresented in the public sector, especially in low-quality jobs (such as communal cleaners) where in 2020 they made up 38.7 percent. A communal cleaner’s job pays 85,000 forints per month (about €212),15 which is not enough to maintain a family or to help Roma woman to get out of the circle of poverty and pursue a better job or education. However, due their lack of education and employment opportunities, they are left mostly with the opportunity of this job or similar ones or nothing.

In order to increase the number of Roma women employed in higher-quality public positions (such as nurses or carers for the elderly), the state aims to continue the program “The Opportunity is Growing” and complement its activities with digitalization. As noted above, this program also been the object of some criticism from the Roma Civil Monitor, which found that its results were unclear and that it had not met its goal.

Physical and Mental Health

Even though there has been some improvement noted by the European Commission in 2019, Hungary still lags behind the EU’s average on life expectancy (76.5 years compared to 81.3 years for the EU). While the life expectancy of the general population in Hungary has increased, Roma people still live five years less (71.5 years) according to the strategy. Their shorter life expectancy is related to poverty and disadvantaged social situation, which influences the ability to have a nutritious diet and balanced mental health or to do sports, as well as the vulnerability to addictions (smoking, drugs, alcoholism, etc.). To improve the health condition of the population, the strategy aims to make health care more accessible to those who live in bad socioeconomic situations, including the Roma. These measures, which here too are a continuation of those in the first strategy, include prevention programs, improving the infrastructure of the hospitals, and public health screening tests. The new strategy also states that the vaccination of Roma girls against human papilloma virus is almost complete in Hungary, which is a major achievement.

While the health situation of the Roma is still worse than that of the non-Roma population, Roma women are fare be better than Roma men. Looking at planned health measures, it is striking that there is no specific measure planned to improve the health conditions of the Roma population. The only thing that is mentioned regarding Roma women is the importance of “The Opportunity is Growing,” which was previously presented as an employment measure. While this program focuses more on increasing the employment opportunities among Roma women, increasing their employment in the health care system might also have a positive impact on their health situation. Because racism negatively affects the way Roma people interact with health care institutions—with mistrust on both sides, Roma being denied access to quality treatment, Roma being blamed for their illnesses, etc.—the presence of Roma women as nurses and carers might lead to more attention to Roma patients and more trust on their part.

Roma Identity and Community Building

Regarding ethnic education—which mostly refers to cultural, historical, and social education of the Roma—the new strategy again highlights the Bari Shej program, which educates Roma girls on “special cultural and social Roma characteristics,” such as the family roles of Roma women and early family formation.

The strategy implies that there are cultural and social characteristics that affect Roma women and girls in their communities and, therefore, that they should be assisted by an outsider mentor who helps them to overcome these characteristics. The strategy does not state clearly what these characteristics are, but throughout it gives a sense of what this refers to. In mainstream society, Roma culture and traditions are viewed as backward, oppressive for women and girls, not progressive, and often violent. Based on these assumptions, non-Roma society thinks that Roma girls and women need saviors in the form of mentors who guide them through these social and cultural characteristics. This kind of approach is racist and sexist because it makes false assumptions about Roma traditions without understanding their broader political, cultural, social, and economic context, and also because it ignores the agency of Roma women and girls.

Contributions from the RCM and Phenjalipe

The Roma Civil Monitor has great potential for monitoring national Roma strategies and performing gender checks. Its importance rests on different pillars. According to Bernard Rorke, of the European Rights Center, the RCM reports produced the most critical observations and evidence about the previous Roma integration strategies and its results.16 They provided important feedback for the European Commission and other EU institutions about the real results of the financial and expert support that they provided to the member states with regard to Roma inclusion. Hopefully, this will continue in the next eight years.

Some of the RCM’s reports contained analyses of how the first Hungarian integration strategy targeted and carried out measures regarding Roma women and girls—this could be expanded now. The new coalition for the RCM has already started its work to monitor the measures and results of the country’s new strategy. The RCM should prepare clear guidelines for Hungary’s CSOs on how to monitor, analyze, and evaluate the measures in the second strategy from a gender perspective. This monitoring, analysis, and evaluation should not concern only those measures in which Roma women and girls are specifically mentioned but the strategy as a whole.

The RCM also gives a great opportunity for Roma and pro-Roma CSOs to take more responsibility and visibility in the work of the members states for Roma inclusion. While for many years, Roma CSOs (and civil society in general) were not taken seriously and were pushed to the margins, now they get the opportunity to raise their concerns, to use their expertise, and to help shape Roma inclusion policies in their countries (if the state makes this possible). Therefore, the RCM also provides one of the best opportunities for Roma gender experts to engage in this process and raise questions, to challenge different political and civic actors, and to provide their expertise to better implement the new Roma integration strategy in Hungary. Roma women, feminist, and LGBTQA+ organizations should thus be empowered and financially supported to take part in the RCM where they could provide their expertise on gender issues.

At this very early stage of the implementation of Hungary’s new Roma integration strategy, what can be said is that a gender and intersectional approach was missing in planning the measures. There are many problematic elements in the strategy that should be closely monitored, in which the RCM could be a great help.

One of the most relevant and interesting policy documents produced on how national Roma integration strategies should address women and girls is the Strategy on the Advancement of Romani Women and Girls (2014–2020) by the International Roma Women Network Phenjalipe in 2016, facilitated by the Council of Europe.17 Phenjalipe is a network of Roma women activists and experts in different fields who have been working with Roma women and girls for many years. Its strategy is presented as “a response to the needs expressed by Romani women activists and civil society, human rights institutions, professionals working on gender equality and Romani women’s issues, governments, and policy makers.” Its objectives are to advance the situation of Roma women and girls in Europe and beyond by taking as a starting point what Roma women and girls say are their priorities.

The document produced by Phenjalipe has a different approach to the inclusion of Roma women than Hungary’s two national strategies. It identifies six objectives:

- Combating racism, anti-gypsyism, and gender stereotypes against Roma women and girls.

- Preventing and combating various forms of violence against Roma women and girls.

- Guaranteeing equal access to public services for Roma women and girls.

- Ensuring access to justice for Roma women.

- Achieving adequate and meaningful participation of Roma women in political and public decision-making.

- Mainstreaming gender and Roma women in all official policies and measures.

These objectives also include action points and refer to state institutions, which makes it even more detailed and concrete. Looking at them reveals key areas that the Hungarian strategy fails to identify when it comes to Roma women and girls, such as tackling anti-gypsyism, ensuring access to justice, participation in political and public decision-making, and mainstreaming Roma women in all policies and measures. The inclusion of these missing areas could make a real difference in improving the situation of Roma women and girls in Hungary, since most of the inequalities that affect them originate during decision-making processes. Therefore, while Hungary’s Roma strategy offers some “treatment” for few symptoms, it does not address the real causes of inequalities concerning Roma women and girls in the way the Phenjalipe document does.

At the time of writing, there is no information as to whether Phenjalipe’s strategy has been even partly implemented in any European country. Its importance lays in the fact that it was specifically written by Roma women experts, who have a greater understanding and expertise on how the situation of Roma women and girls could be improved. While it was facilitated by the Council of Europe and not the EU, nothing would have prevented Hungary, as a member of both bodies, to use this strategy as a guideline.

It should be noted, however, that even Phenjalipe’s strategy lacks some actions for advancing certain groups of Roma women and girls. It does not address the concerns of older women, women living with disabilities, trans women, lesbian women, women living in rural areas, girls in segregated schools and areas, sex workers, and so on. These groups face additional oppression not only in the mainstream Hungarian society but also in the Roma communities. Empowering these further marginalized groups of Roma women and girls requires special attention, dedicated budgets, well-planned measures, and cautious monitoring.

Conclusion

The efforts by Hungary to address the needs of Roma women and girls through its two integration strategies raise several concerns. A gender analysis of the strategies shows there has been some progress. Given that in Hungary gender equality is in trouble and does not seem to be a priority for the government, the simple fact of mentioning and addressing some of the issues that Roma women face and paying special attention to minority women shows that there is some hope. However, a close look at the content of the strategies and at the planned or already implemented measures for Roma women and girls shows that there have been serious false assumptions, a lack of involvement of Roma women in designing the strategies, a lack of interaction with Roma-led CSOs, and latent sexism, racism, and homophobia.

Roma women being only addressed in the first strategy in the section titled “The situation of Roma women” gave the impression that they are somehow separate from society and need very targeted measures that do not concern anyone else. Yet, early pregnancy, equal access to health care and public services, and better employment opportunities are concerns not only for Roma women but also for non-Roma women living in poverty and disadvantaged circumstances. However, because of the additional oppression Roma women face due to racism, they do need more targeted measures that focus on the racism dimension as well as the gender one. Therefore, a combination of a gender mainstreaming approach and an intersectional one that more purposefully tackles racism and gender would be the most effective way to help Roma women. The gender mainstreaming should focus not only on gender as a social category but also on factors such sexuality, age, and religion. It is very common mistake in gender mainstreaming to take gender as a synonym for women, which is not true. Gender identity is in a strong multi-angled relationship with all these social constructions that should to be emphasized in any integration strategy.

Furthermore, none of the suggestions for improvements from sources such as the RCM or Phenjalipe can be fulfilled without the true commitment of not only Hungary’s government but also the European Commission. To improve future national Roma strategies there needs to be political a “political push” from the European Commission and the setting of minimum standards for the member states for developing their own strategies. Although the EU Roma Strategic Framework is a good step, member states still take it only as a guideline and not a standard when designing their national Roma strategies. Hungary is clear example of this. While the EU Framework clearly emphasizes the importance of fighting anti-gypsyism and of empowerment, which are essential elements for the inclusion of Roma, especially women, the Hungarian strategy lacks these aspects. The case of Hungary is not unique; there are similar problems in other member states as well. Implementing the recommendations below would therefore lead to the improvement of not only Hungary’s Roma strategy but at the EU level as well.

In order to better address the needs of Roma women and girls in Hungary, the government should adapt Phenjalipe’s Strategy on the Advancement of Romani Women and Girls to its local context by reworking it with Roma women experts from diverse backgrounds, such as sex workers, trans women, lesbian women, rural women.

As Hungary is part of the Roma Civil Monitor initiative, the European Commission’s Directorate-General for Justice and Consumers as its managing entity, should develop and fund clear guidelines for the RCM on how to conduct gender analyses of national Roma strategies, their implementations, and their monitoring. These guidelines should be written by Roma women and LGBT experts from diverse backgrounds.

The European Commission should define minimum standards and clear indicators that specifically target Roma women and girls, and use its political influence to make Hungary and other member states adopt these.

There has been great work invested into improving the situation of Roma women by the EU institutions, Europe’s Roma civil society, Roma and pro-Roma experts, and national governments, and that has influenced Hungary. However, this is still not enough. It is not enough to mention Roma women and girls in strategies. It is counterproductive to rely on old and false assumptions about Roma culture and traditions. It is not right to forget about Roma lesbian, bisexual, trans women, and other Roma women from the LGBTQA+ community. If national integration strategies leave out repeatedly certain groups of people, there will be never a true and whole dedication and commitment to improving the situation of Roma women. Roma women, even just taking the example of Hungary, form a very diverse group in terms of the situation they face, which should determine what kind of approach and measures need to be taken to improve their situation. There is no one-size-fits-all approach toward any minority issues because the problems are complex and structural. While there are no perfect strategies, governments have to make sure that they do their best. To obtain effective results, Hungary’s authorities have to work with Roma gender experts and invest more into intersectional approaches, methodologies, and knowledge. Until this happens, Hungary will remain an unequal country for Roma women and girls.

- 1European Commission, EU Framework for National Roma Integration Strategies, 2010.

- 1European Commission, Report on equality between men and women in the EU 2018, April 13, 2018.

- 2Women's Rights and Economic Justice, Intersectionality: A tool for Gender and Economic Justice, August 9. 2004.

- 4Fundamental Rights Agency, Second European Union Minorities and Discrimination Survey — Roma Women in Nine EU Member States, 2019.

- 5Bulgaria, Croatia, the Czech Republic, Greece, Hungary, Portugal, Romania, Slovakia, and Spain.

- 6European Roma Rights Center, Written Comments of the European Roma Rights Center Concerning Hungary, April 5, 2013.

- 7European Parliament, Country Report on Hungary – Empowerment of Romani Women Within the European Framework of National Roma Inclusion Strategies, 2013.

- 8European Parliament, Country Report on Hungary – Empowerment of Romani Women Within the European Framework of National Roma Inclusion Strategies, 2013.

- 9European Commission, Report on the implementation of the EU Framework for National Roma Integration Strategies, 2014.

- 10European Commission, The social and economic integration of the Roma in Europe, 2010.

- 11European Roma Rights Center, United Nations: Hungary Coercively Sterilized Romani Woman, August 31, 2006

- 12Roma Civil Monitor 2021-2025, 2022

- 13European Commission, A Union of Equality: EU Roma strategic framework for equality, inclusion and participation, October 7, 2020.

- 14European Roma Rights Center, Life sentence: Romani Children in State Care in Hungary, 2011.

- 15Officina, Közmunkabér 2022 összege: ennyivel növekszik a közfoglalkoztatási bér 2022-ben, [The amount of the public employment wage in 2022: this is how much the public employment wage will increase in 2022,] 2022.

- 16European Roma Rights Center, Why Roma Civil Monitor Matters, April 26, 2022.

- 17Council of Europe, Strategy on the advancement of Romani women and girls (2014-2020), 2016.