Alliances in a Shifting Global Order: Rethinking Transatlantic Engagement with Global Swing States

Alliances and strategic relations around the world are being redefined by the Russian war against Ukraine and growing US-China competition and tension. These geopolitical developments, alongside other recent economic and security crises, call for a rethinking of US and European engagement with key actors in Latin America, Africa, the Middle East, and the Indo-Pacific. States with significant leverage in international affairs but varying preferences for cooperation—known as “global swing states”—have become increasingly relevant interlocutors to address global challenges. For the transatlantic partnership, a better understanding of the swing states’ strategic interests and priorities is essential for reinforcing cooperation with them in the current, shifting geopolitical environment. Building on a 2012 GMF report that coined the term "global swing states" and the GMF Geostrategy team’s work on the future of alliances, this publication presents innovative research and concrete recommendations for shaping that cooperation.

Read the report as a PDF, explore the graphs more in-depth, or jump to each country's profile:

Foreword

by Heather A. Conley

The international system is undergoing a profound transition that began in earnest in 2012 with the return of Vladimir Putin to the Russian presidency and the installation of Xi Jinping as chairman of the Chinese Communist Party.

In November of that year, GMF and the Center for a New American Security captured the earliest days of this geopolitical shift in a ground-breaking report that described the role of the so-called “global swing states” and their impact on the future of the international system. More than a decade later, GMF is reviving its assessment of these states as global fragmentation and direct challenges to the UN Charter increasingly characterize an emergent two-bloc international system, with a rules-based West pitted against an evolving Sino-Russian, and increasingly Iranian, axis.

Reassessing the role of the global swing states, sometimes referred to as middle powers because they seek to emerge in their own right, in light of these developments is urgently needed. A former editor of China’s nationalist Global Times has already offered his crude appraisal of these states, noting that “corralling a few dogs, even a pack, is easier with two lions [China and Russia] than with one.”

The countries highlighted in this report share certain characteristics. All are highly pragmatic and self-interested, seek national and regional advantage, and do not see themselves bound to an American-led international order. Some aspire to an ascendant place in the international system. The Kremlin considers at least one of them, India, a “friendly sovereign global [center] of power”.

Transatlantic partners must think boldly, diplomatically, and economically to engage more effectively with the swing states, or middle powers, in a two-bloc system. Readers will find country-specific chapters on Brazil, India, Indonesia, Saudi Arabia, South Africa, and Turkey, and a conclusion with recommended courses of action. The West, erroneously, all too often lumps together the swing states and other countries that either choose to be or fall in between the two emerging blocs as the Global South, but this label reflects a lack of intellectual rigor. These countries are diplomatic and economic entrepreneurs at a moment of international opportunity. Can they reap benefits from both blocs while pursuing and achieving their own national and regional aims? Is this a bidder’s bazaar where competition between the two blocs and its ensuing transactionalism supersede international law and norms? And, most importantly, how do these states view the future of international engagement?

The answers to these questions will shape the future of the international system and the inherent strength of US-led global alliances, particularly the transatlantic relationship.

Fluid Alliances in a Multipolarizing World: Rethinking US and European Strategies Toward Global Swing States

by ALEXANDRA DE HOOP SCHEFFER

Russia’s war on Ukraine has accelerated three structural trends that have been reshaping global affairs since the end of the Cold War: the erosion of the post-1945 order and challenges to US global leadership; strategic competition between the United States and China; and the rise of regional powers to the status of global powers. This period of geopolitical transition demands a rethinking of US and European international statecraft if the transatlantic community is to retain its extensive influence.

A full-scale reconfiguration of global alliances is now underway, forcing states to position themselves in relation to new dynamics of strategic competition. Many countries are choosing to maintain fluid relations in different realms of international affairs to exploit opportunities from steadily growing Sino American competition. These “global swing states”, a term initially coined by GMF and the Center for a New American Security in 2012, and updated in this publication in the light of the war in Ukraine and the current great-power rivalry, seek to increase their influence in global affairs by cooperating with the United States, China, Europe, and Russia, without giving any of them an exclusive commitment. Given this growing global geopolitical and economic reach, swing states are playing a pivotal role in their respective regions, shaping policies on key transnational issues such as climate change, global health, and internet governance, and assuming a more active role in crisis diplomacy. They seek to escape a bipolar logic and pursue a multialignment strategy.

Drawing on GMF’s global network of offices and fellows, this publication provides in-depth and cross regional analysis of the “swing strategies” of six key states—Brazil, India, Indonesia, Saudi Arabia, South Africa, and Turkey—and formulates policy recommendations for the United States and European powers to engage with the swing states, thereby preserving transatlantic influence over the shape of the international order.

New Patterns of International Cooperation

Global politics has entered an era of more competition and less cooperation. The world order has become more fragmented, increasingly split between Washington- and Beijing-led blocs that take different approaches to economic, security, technology, and social policy. The World Trade Organization’s and UN Security Council’s structural issues have only worsened as they become epicenters of these opposing perspectives. Both agencies, and other post-World War II institutions, exhibit increasing dysfunction after failing to address recent challenges such as the COVID-19 pandemic and the war in Ukraine. An increasing number of countries are consequently rejecting the US-led, Western concept of international order and striving to create their own norms on human rights and technology, among other critical global issues.

The United States sees China increasingly co-opting multilateral forums and prefers to invest in international cooperation through bilateral or regional formats with like-minded countries, such as AUKUS and the Quad in its Indo-Pacific (Australia, India, Japan, and the United States) and transatlantic (France, Germany, the United Kingdom, and the United States) versions. Beijing, no longer content to adhere to the existing global order, is simultaneously building its own institutions and channels, including development banks and inter-regional security organizations. Chinese President Xi Jinping has called on his country to “lead the reform of the global governance system” by pursuing a multipronged strategy. He seeks the status quo when it aligns with national goals and norms, as the World Bank and the Paris Agreement on climate change do, and he seeks change when national vulnerabilities are exposed, as they are in the global financial system and international technology standards, or when Chinese norms differ from those of the current system, as they do regarding human rights. In these latter cases, China undermines Western values and creates alternative institutions.

The Trump administration’s retreat from global leadership gave China an opportunity to fill the void and promote multipolar global governance. That administration also normalized transactionalism and disruption in international affairs, boosting a trend toward more fluid and reversible alliances.

Swing states seek to find their place in this world, as new coalitions emerge. They seek alternatives to the present order, but another structure, whether economic or political, has yet to emerge. SinoAmerican interdependence in a globalized economy means complex consequences for a rivalry that impacts multiple global actors, each uniquely.

Unsurprisingly, these developments have made regionalization more consequential than globalization, with more than half of international trade, investment, and the movement of money, information, and people now occurring within regions. From India to Argentina, from Brazil to South Africa, and from the Middle East to Southeast Asia, nations and regions are accelerating efforts toward arrangements aimed at reducing their dependence on the US dollar. They fear that the United States could use its currency’s power to target them as it has a sanctioned Russia. The swing states also recognize China’s growing ability to provide its trading partners with goods that they need, including advanced technology.

The future of a healthier international order will likely depend on stronger regional structures. The transatlantic community, if it is to protect its interests, needs to work with these structures, and that means working more effectively with swing states.

Strategic Multialignment

Three major events in the last two decades have accelerated the unfolding geopolitical shift: the 2003 US-led war in Iraq, the 2007-2008 financial crisis, and the election of Donald Trump to the US presidency. These developments durably weakened American moral, economic, and geopolitical stature, bolstered a perception of Western decline, and incentivized traditional allies to seek strategic autonomy from Washington. They also emboldened China to alter its foreign policy, particularly by expanding its military presence in the South China Sea and diversifying its supply chains away from the United States, and to demonstrate the successes of its economic nationalism. At the same time, the US model of liberal democracy is increasingly questioned at home and abroad. GMF’s Transatlantic Trends 2022 revealed that 30% of Americans perceive their democracy to be “in danger” while 32% of Italians and Poles, and 19% of the French, have the same assessment of their own democracies. This has foreign policy implications, as swing-state allies grow distrustful of Western political systems and begin to seek independent approaches to regional and international relations.

Many mid-sized powers no longer feel any imperative to align with the United States. Brazil, India, and South Africa are among the countries seeking strategic diversification, including through deeper ties to Russia and China. Nonalignment, which served as a counterweight to the Western-led world order during the Cold War, has morphed into multialignment, and the world’s growing multipolarization offers more opportunities for transactionalism all around. The United States’ traditional allies increasingly seek strategic emancipation from Washington when interests diverge. An assertive China and a dysfunctional United States mean many countries move between the two powers as necessity dictates. This strategic diversification translates into pragmatic foreign policies based on flexible, interest-driven, and issue-specific cooperation that support short-term objectives.

In this context, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has been a clarifying moment for alliances. The conflict brought together the United States, Europe, and their Indo-Pacific partners on sanctions policy against Russia and concerted military assistance for Ukraine. However, they have been less successful isolating Russia and its allies. The first UN General Assembly resolution condemning Kremlin aggression, proposed in March 2022, elicited 35 abstentions, more than half from African states. In East Asia, only Japan, Singapore, and South Korea strongly supported the resolution. The region’s biggest powers, China, India, and Indonesia, refused to take a stance.

The narratives of “the West versus the rest” or “democracies versus autocracies” quickly became irrelevant and counterproductive given the many interdependencies between Russia and many Asian, African, Middle Eastern, and Latin American countries. These states depend on Russian gas, arms, and fertilizer imports, while Russia needs their natural resources and wide-ranging trade relations to fuel its economy and war effort, and their political support for rejecting a US-led global order and extraterritorial sanctions. Russia’s and China’s shuttle diplomacy to African and Latin American capitals aims at cementing collaboration.

The swing away from the West is evident as crisis diplomacy increasingly moves outside its domain. Brazil’s recent proposal to mediate, with China and the United Arab Emirates, an end to the war in Ukraine, and China’s 12-point framework for peace, are two examples. Turkey’s successes in securing a deal between Russia and Ukraine to export grain via the Black Sea and in arranging prisoner-of-war swaps are others. China’s brokering of an agreement to reestablish diplomatic relations between Iran and Saudi Arabia is yet another, brought on by Beijing’s agility to exploit Saudi distrust of the United States and reduced US leadership in the region.

These non-Western diplomatic initiatives reflect mid-sized powers’ growing activism in international politics, which has come about after decades of Western disengagement and strategic failures in the Middle East and Africa. The United States and its allies will continue to see their global influence wane unless they take steps to reverse the trend through greater engagement with these powers.

A New Approach Toward Global Swing States

The transatlantic community can do this by:

Diversifying relationships. Transatlantic engagement with global swing states is of paramount importance in the shifting geopolitical environment. To offer an alternative to the bloc mentality, which swing states seek, the United States and Europe should broaden and diversify their relationships with these states to address a wider range of topics of mutual interest. At the same time, the transatlantic partners must accept a compartmentalization of those relationships: A lack of cooperation in some areas should not prohibit collaboration in others. Ties to China, simultaneously a competitor, partner, and rival, serve as a precedent.

Showing greater flexibility. Compartmentalization requires more flexible approaches to cooperation. Washington must adapt to achieving foreign policy goals without the formal alliances that served as the bedrock of the US-led world order. The complexity and nuance of bilateral relations is increasing as partnerships become more fluid and the benefits of hedging between China and the United States are perceived to grow. Europe, in particular, should informally but systematically engage swing states by identifying and pursuing mutual interests, thereby carving out a role in mitigating the consequences of great-power competition.

Not forcing a choice. The United States and Europe must refrain from using binary narratives to make new formats of cooperation appealing to partners. Structuring contemporary geopolitics around a competition between autocracy and democracy is counterproductive. It reflects a blindness to the complexity of global swing states’ strategic interests and rests on the questionable assumption that the West can legitimately divide the world in normative terms. The “us-versus-them” nature of the Cold War does not apply to the current global order.

Strengthening transatlantic dialogue and policy coordination. A reset of transatlantic dialogue and policy coordination on China, Russia, and the Global South is a strategic imperative for the United States and Europe if they are to retain their ability to shape or influence the international order. This conversation should focus on boosting constructive and pragmatic dialogue with regional powers on the global challenges affecting them as they seek collective solutions, notably on climate change, health, agriculture, and energy security. Existing multilateral forums, especially the G20, should serve as the venues for this dialogue and transregional cooperation. Transatlantic partners must consider the growing North-South divide, engage in confidence-building measures, and rely less on coercive diplomacy. Deeper Western trade, diplomatic, and strategic relations with the global swing states would also reduce their dependence on Russia and China and counter the two countries’ efforts to drive a wedge between transatlantic allies and the Global South.

Not dismissing mediation by others. Russia’s war on Ukraine can serve as the first litmus test for a new transatlantic approach to fluid alliances in a multipolarizing world. The United States and the EU should heed non-Western efforts to mediate the conflict as they will influence the compromises made to restore peace. US President Joe Biden and French President Emmanuel Macron have already recognized the importance of “engaging” China to contribute “in the medium term to ending the conflict”. To ensure that the war does not end on Russia’s terms, the transatlantic partners, with their Indo-Pacific partners, need to seize opportunities to embed such diplomatic initiatives in broader transregional initiatives. September’s G20 meeting in New Delhi offers an opportunity to do that.

Methodology: Conceptualizing Global Swing States

by GESINE WEBER

The idea of “global swing states” is not new to the field of international relations and geopolitics. Richard Fontaine and Daniel Kliman coined the term in “Global Swing States: Brazil, India, Indonesia, Turkey and the Future of International Order” more than ten years ago.

Building on their work, this publication examines swing states in the new, current geopolitical environment. It provides a comparative research framework for these states, and maps preferences of cooperation through an innovative, mixed methods approach.

Definition and Concept

The concept of “global swing states” is inspired by the term “swing states” in US domestic politics. In the context of geopolitics, however, a swing state, as defined in this study, is one with significant leverage in international politics but varying preferences for international cooperation.

These preferences are more complex than alignment with one global power, and this study refrains from asserting that a swing state could be “flipped”. Instead, this publication introduces the concept of a “swing range”, acknowledges that preferences for cooperation shift, and recognizes that international cooperation is not a zero-sum game. The study assumes that states may engage simultaneously with different partners on the same or similar issues. Flexible cooperation and hedging strategies exist and are regularly pursued.

More Than Six

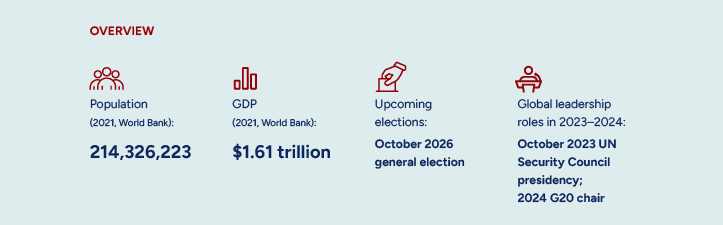

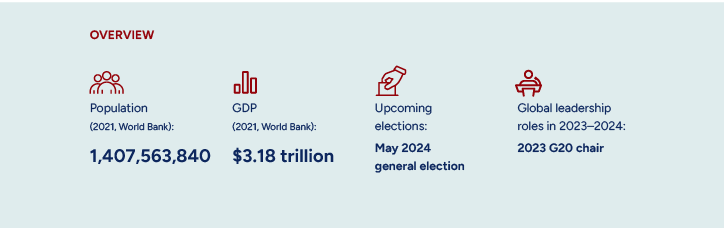

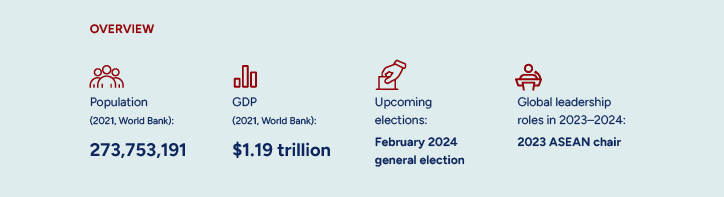

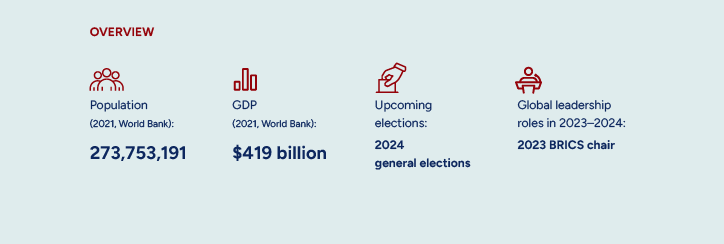

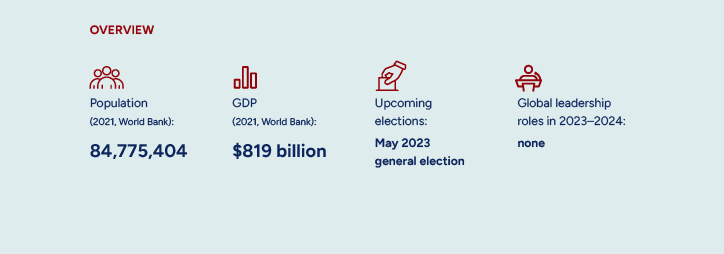

This study maps preferences for cooperation of six countries: Brazil, India, Indonesia, Saudi Arabia, South Africa, and Turkey. They were selected for five reasons. First, they are all G20 members, whose economic weight makes them important partners for the United States and Europe. The G20, particularly in recent years, has served as an increasingly important forum for cooperation on, for example, negotiations for introducing a global minimum tax. Second, the six countries individually have enough political and economic heft to make them regional powers. Third, some have or will soon assume roles that raise their influence. India holds the G20 presidency this year, as South Africa chairs the BRICS group. Brazil will hold the UN Security Council presidency in October. Saudi Arabia is an increasingly important energy partner for Europe. Fourth, some are holding elections whose results may well have significant repercussions beyond their borders. Turkey will have a presidential and parliamentary vote in May. Indonesia will hold its general election in 2024. Lastly, the countries selected are geographically dispersed.

This publication does not assert that the six selected countries are the only swing states. India and China, among others, see many European countries as swing states since they rarely limit their engagement on a given issue to one partner.

This publication is consequently a transatlantic contribution to discussions on the geopolitics of alliances. It is part of a broad debate that transcends Europe and the United States.

Mapping a “Swing Range”

The innovative, mixed methods approach used in “Alliances in a Shifting Global Order: Transatlantic Engagment with “Global Swing States”” translates qualitative research on state preferences for cooperation into a coding system that permits comparative analysis and the ability to visualize and identify patterns.

For each country examined, the research focuses on preferences for cooperation with the United States, Europe, China, and Russia, and, when appropriate, other states, in four aspects of international affairs: security, economics and trade, technology, and international order. “Europe”, in this context, combines EU member states, European NATO member states, and the EU institutions. “Other states” includes those that are not global powers. They are, however, primarily countries in the Global South or the Persian Gulf.

The four aspects of international affairs consider national interests in and policies on the following subtopics:

Security: Ukraine, the Indo-Pacific, regional and neighborhood security, defense agreements, and defense production and procurement

Trade: economic sanctions, trade balances and preferred trade partners (including for foreign direct investment), World Trade Organization reform, and energy

Technology: infrastructure, cybersecurity, and aerospace

International order: support for a rules-based international order and belief in a global competition between democracy and autocracy

The qualitative data in these areas is then converted into quantitative data according to a coding scheme:

|

Code |

Cooperation with the United States/ Europe/ China/ Russia/ other partners is… |

|

5 |

the clear preference, “go-to” option, first reflex, or natural choice |

|

4 |

preferential or an important pillar of partnerships/alliances, but not a top priority |

|

3 |

desirable, but one among other preferred options |

|

2 |

an option among many, even if not preferred, or valuable for pragmatic ad hoc cooperation |

|

1 |

possible, but a “necessary evil”, and among the least desirable solutions |

|

0 |

completely undesirable or nonexistent |

This coding scheme is used for creating a radar-like graphic that displays a “swing range” that reflects the six swing states’ preferences for cooperation with specific actors.

Three “swing range” scores exist: an aggregate score, which bundles cooperation preferences across policy areas; aggregated scores for a given policy area; and (on the GMF website) disaggregated scores for an individual issue within a broader policy area. The scores are rounded to the nearest digit.

It is important to note that the scores must be understood only as an early 2023 snapshot of preferences for cooperation. The foreign policies of the United States, Europe, China, and Russia are, admittedly, dynamic, and policy changes may well cause swing states to adapt their preferences for cooperation, thereby altering the quantitative analysis presented in this study.

Disclaimer and Acknowledgements

The opinions expressed in the individual sections of this publication are exclusively those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publication’s other contributors or of the German Marshall Fund of the United States (GMF).

GMF thanks Catalina Raileanu from QuickData for the report’s design.

Setting the Scene: Global Swing States in a Shifting Geopolitical Environment

Why Aren’t Swing States Swinging Toward US?

by MICHAL BARANOWSKI and THOMAS KLEINE-BROCKHOFF

The Russian invasion of Ukraine on February 24, 2022, dealt a final, fatal blow to a European security system built on the principles of the Charter of Paris and the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). Those principles aimed at creating a system with Russia, not against it. Yet the war’s implications go far beyond Europe. The conflict exposed the reality of the shrinking reach of the post-Cold War world order. No name exists for the current era, now a year old, but the post-Cold War relative stability in the Euro-Atlantic area is clearly not a part of it.

With his invasion, Russian President Vladimir Putin hoped not only to subjugate a sovereign state but also to break transatlantic unity and reshape Europe so that the Kremlin could (re-)establish a sphere of influence over its neighbors. Putin also aimed to extend this geopolitical dynamic to Asia by forging a new relationship with China. But instead of crumbling, the transatlantic alliance, in close partnership with US allies in Asia, especially Australia and Japan, responded to Russian aggression by standing with an embattled Ukraine. Putin’s bet on scoring a quick victory and delivering a blow to the broader, democratic West failed. His war instead laid bare a global split between the United States and its European and Asian allies on one hand and the autocratic camp of Russia and China on the other.

The conflict has been a rude awakening for Western countries, but not because many industrialized democracies failed to recognize Putin’s neo-imperial designs and his cruel determination to assault Ukraine. Rather, the consternation stems from the unwillingness of many nations of the Global South to join the Western coalition. Why did “they” not join “us” from the start? Why aren’t even the swing states, the larger democracies of the Global South, on “our” side? Why do they share “our” values but not “our” outlook and policies? Why such reticence to openly condemn the aggression and such reluctance to join sanctions and send arms and ammunition? Why this artful balance, this hedging, with occasional sympathy for the aggressor?

Western countries started to recognize the situation at a March 2, 2022, UN General Assembly emergency session. Forty countries voted against or abstained from a resolution condemning Russia’s aggression, among them India and South Africa. Even the votes in favor masked a broad unease with Western policies. Of the 141 countries supporting the resolution, only 46 enacted sanctions against Russia. The huge Indo-Pacific region alone had a wide range of responses to the West’s message:

While one country (North Korea) opposed the UN resolution and six countries (China, India, Laos, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, and Vietnam) abstained, only six staunch US allies (Australia, Japan, New Zealand, Singapore, South Korea, and Taiwan) joined in the sanctions. Awkward moments arose on other occasions, too. When, nearly a year into the war, German Chancellor Olaf Scholz visited newly elected Brazilian President Lula da Silva it was all smiles until Scholz asked Lula to support Ukraine, in part with ammunition. The host then gave his guest the cold shoulder.

Brazil and India are the most outspoken among the noncommitted. Others lie low and say little but tacitly agree with the two giants. In both cases, their positions triggered Western soul-searching: What did “we” miss? Are the swing states deliberate fence-sitters? Or did they swing to the other side and, if so, why? Did “we”, perhaps too confident about the righteousness of “our” cause, miss a geopolitical distancing?

The most obvious jolt is closer to the war. Turkey, as a regional actor, has a stake in the conflict, and, as a NATO member, should not be a swing state. In that sense, the country may be the most unusual and atypical of the lot. But all have similarly clear motives for their position, and these motives fall into four broad categories: the perceived hypocrisy of Western governments’ anti-Russian stance; the inability to quickly overcome a dependence on Russia; a preference for less risky hedging over siding with the West; and a desire to hasten the advent of a post-Western, multipolar world in which swing states need not take a side.

To most Western observers, responsibility for the war is evident. But in swing states from Indonesia to South Africa, and from India to Brazil, attributing blame is more complex. Indian Foreign Minister Subrahmanyam Jaishankar has been blunter than other swing state officials when speaking of purported European double standards. “If I were to take Europe collectively, which has been singularly silent on many things which were happening, for example in Asia, you could ask why would anybody in Asia trust Europe on anything at all. … I can give you many instances of countries [that] have violated the sovereignty of another country. If I were to ask where Europe stood on a lot of those, I am afraid I’ll get a long silence,” he said. During another interview he added, “Europe has to grow out of the mindset that Europe’s problems are the world’s problems, but the world’s problems are not Europe’s problems.” Analysts such as Amrita Narlikar, president of the German Institute for Global and Area Studies, decry that Americans and Europeans “have no problem lecturing countries like India about democracy, human rights, and environmental protection. They demand support for Ukraine or other noble causes while at the same time deepening their own business relationship with China.”

The sense of Western hypocrisy allows swing states to cloak their own hesitancy in moralism. But there are also more practical reasons for their reluctance to join the Euro-Atlantic bandwagon. Some countries think they cannot afford to alienate Russia given the benefits of good relations. For poorer nations, these include reasonable energy prices, which are indispensable. Links between national security and the Russian defense industry are another strong driver of loyalty to the aggressor. Russia has significant leverage over India, for example, as long as New Delhi depends on Moscow for the flow of advanced weapons systems, especially fighter jets, cruise missiles, and submarines.

Similarly, South America has concerns about its trade balance, which is often cited as a reason for silence. Here, however, the worry is that siding with the United States could alienate China. South American countries, vulnerable to even small changes in trading patterns, want to avoid reprisals from taking a side in the great-power rivalry. The current war, which adds a third great power (or former great power) to the mix, and one that is increasingly close to China, heightens the unease. It is simply less risky to stay out of it all.

For some time, several swing states have seen no benefit in accepting a binary world order. Liberal versus illiberal, democratic versus autocratic, Beijing’s rules versus Washington’s rules—such dichotomies are all based on a leading US role, which these countries do not necessarily accept. To them, a narrative about values sounds like “the West against the rest”. Munich Security Conference Chairman Christoph Heusgen has warned that Western countries must avoid finding themselves confronted with a global majority that “buy[s] into the Sino-Russian narrative”.

India has aligned itself for some time with Russia’s polycentric vision of the world. Now, India and other countries on the fence, after decades of US supremacy, demand to be heard. For them, it is, at a maximum, payback time. At a minimum, it is a time of increased options. In this environment, India’s avoidance of taking sides is less surprising than its attempt to distance itself from Russia, even if not far enough for Western tastes.

That Western countries are awakening to swing states’ skepticism and distrust may be a silver lining of the war. The West has started to consider adapting its narrative. Would it be better to replace “democracy versus autocracy” with “accountability versus impunity”, as former British Foreign Secretary David Milliband suggests? Or should cultural relativism just be attacked outright and exposed as a Sino-Russian plot to weaken the concept of human rights and, thereby, the West?

Western countries, if they want swing states’ support, must start paying more attention to those states’ concerns. Such support will be vital for the outcome of future geopolitical competition, even if it has only a very limited impact on the outcome of the Ukraine war. Power matters and, in war, hard power matters more. A victorious Ukraine will surely move the hedgers and fence-sitters.

China: On the Russian Axis

by BONNIE S. GLASER and ANDREW SMALL

Once dismissed as a marriage of convenience, the China-Russia relationship is instead at the core of a new bloc politics. In the years following Russia’s 2014 annexation of Crimea, Beijing and Moscow made a concerted effort to minimize outstanding points of friction and create the conditions for an enhanced, mutually enabling set of political, security, and economic ties. Their February 2022 joint statement was its crystallization, the “no limits” language an unexpected, yet accurate reflection of their once-unthinkable cooperation in so many areas, from joint development of military technologies to coordinating action in other geographic regions. Political scientist and former Carnegie Moscow Center Director Dmitri Trenin characterized it at the time as taking the relationship “to the level of a common front to push back against US pressure on Russia and China in Europe, Asia, and globally”.

The Russian invasion of Ukraine has not fundamentally changed this dynamic. Despite its struggles on the battlefield and the sanctions squeeze, Moscow remains a partner of unique value to Beijing in the wider geopolitical struggle with the West. Bilateral trade has soared since the invasion, the two countries have increased the frequency of their joint military exercises, and China has provided tailored support, including semiconductors, dual-use goods, the use of Chinese supertankers for Russian oil shipments, and the deployment of pro-Russian propaganda across the Global South.

Most policymakers understand the real potential of these developments, but Beijing’s pro forma October 2022 statements opposing nuclear weapons threats and its more recent “peace proposal” have revived misplaced hopes that China could play a constructive role with Russia, and that policy differences between the two can be exploited. The coming period will be one in which Sino-Russian coordination and mutual support, in familiar and novel ways, is a defining feature of the geopolitical landscape.

The Battle for the Global South

Swing states play a crucial role in Sino-Russian efforts to build an international political, economic, and security order in the short and long term that supports the two countries’ interests. The invasion of Ukraine has put the swing states in the crosshairs of this endeavor. Beijing sees sanctions on Russia as a harbinger of what it might face if it invades Taiwan or commits other acts of aggression. The urgent diplomatic and economic challenges confronting Russia, from UN votes to oil shipments, are those Beijing is addressing over a longer time frame, including through its new Global Security Initiative and Global Development Initiative.

China and Russia have qualitatively different relationships with each swing state, but the two countries share defensive goals. They wish to ensure that key swing states do not actively align with the United States and its allies in terms of formal military alliances, joining sanctions, or votes in international bodies. These states are crucial to maintaining as expansive and strategically potent a nonaligned grouping as possible. Beijing and Moscow also need the friendly participation of swing states for developing alternative, non-Western-centric diplomatic, financial, technology, and trade structures, and intertwining them. The September 2022 Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) summit in Samarkand, for instance, saw agreement on a roadmap for increasing the volume of trade among member states in local currencies and for using alternative payment and settlement systems.

Conversely, the Kremlin’s invasion has highlighted for the United States, Europe, and their allies the heightened risks of being dependent on China and Russia. The advanced industrial democracies now seek to diversify their economic ties away from the two autocracies, albeit at different speeds. This makes the swing states even more important economic partners for the West and provides a greater impetus to bind them into the trade and technology frameworks of liberal democracies.

The New Bloc Politics

The perception among the swing states of an intensifying bloc competition between a Sino-Russian axis and a US-led grouping of liberal democracies creates new pressures and opportunities for the swing states to exploit. Yet the deepening Sino-Russian relationship does not have a uniform impact on them.

On the one hand, the emerging geopolitical landscape strengthens Beijing’s and Moscow’s capacities to bring these states in line. As Hu Xijin, former editor of China’s firebrand Global Times newspaper, put it, “corralling a few dogs, even a pack, is easier with two lions than with one.” At a minimum, states that might have considered getting on the wrong side of one power are wary about doing so with both. China and Russia, after all, have complementary capabilities and relationships that can be brought to bear. Beijing has financial firepower, while Moscow offers experience with global security operations. In addition, their political, intelligence, and military networks in Asia, Africa, and Latin America that, in some cases, date back to the Soviet and Maoist eras, could be jointly leveraged. With the exception of rounding up UN votes, Beijing and Moscow have not attempted to combine efforts in Asia, Africa, and Latin America, aside from during the early days of the Sino-Soviet alliance in the 1950s. Yet they are now exploring the possibility of doing just that, as their March 2023 joint statement makes clear. China and Russia also offer the prospect of jointly building a sanctions-resilient financial architecture that, with their combined heft as, respectively, the world’s second-largest economy and a major energy exporter, some swing states find attractive.

On the other hand, swing states are wary of being stuck on the wrong side of the emerging bloc politics. A close relationship with China or Russia is one matter, while being perceived as part of an anti-Western Sino-Russian camp is another. SCO and BRICS members already resist when Beijing and Moscow try to push such associations in a more ideological direction. For some swing states, the closer alignment between Beijing and Moscow also complicates their existing relationships with one or the other power. Long-standing ties between India and Russia, for example, are strained when China could address security threats on its western border by asking Moscow to stop being a reliable arms supplier to New Delhi. It is unsurprising, therefore, that India is deepening trade, economic, technology, and security ties with Europe, Japan, and the United States, and is also taking more sympathetic positions on “allied” groupings. India has joined Brazil in opposing Sino-Russian efforts to persuade the International Atomic Energy Agency board that the trilateral AUKUS security pact violates the Non-Proliferation Treaty.

A Global Authoritarian Axis?

The transatlantic allies are still in the early stages of trying to determine how, and even whether, to plan to deal with a China and Russia that operate as a more intertwined global partnership. Understandably, much of the political emphasis at present is on Beijing’s approach to the war and its support for Moscow, even if Chinese efforts to influence public opinion in the developing world on Russia’s behalf are concerning.

The allies have a special focus on India, which is exceptional among the swing states. The country’s leading position in the developing world, its membership in key multilateral institutions, and its unease about Beijing’s geostrategic ambitions make it an especially important partner for resisting SinoRussian initiatives. The United States and Europe have sought to ensure that their handling of India’s relationship with Russia—on which it still depends for its military capabilities—does not negatively impact the wider framework of India’s cooperation with the West. Such cooperation Is conditioned and potentially deepened by shared views on China.

The Sino-Russian “offer” to some swing states will likely improve over time, as competition for their support intensifies, but now is a difficult moment for Beijing and Moscow. China’s Belt and Road Initiative is faltering as the country wrestles with debt restructuring issues throughout the developing world and its domestic economy struggles. Russia’s need to concentrate military resources and political attention on the war in Ukraine have reduced its scope to expand or even maintain its global footprint, notwithstanding the recent joint Sino-Russian military exercises with South Africa. It is consequently a propitious time for the transatlantic allies to offer the swing states more and bring them into commercial, technology, and standards partnerships. The Just Energy Transition Partnerships for South Africa and Indonesia represent the kinds of packages that the West can propose, as are financing tools for trade, security, energy, and technology.

Competition for the swing states will be keen. India, Brazil, and major energy traders such as Saudi Arabia and the Gulf States, are of particular importance to Sino-Russian ambitions to build resilience against Western sanctions. And even states sympathetic to the allies, such as India, may still prefer to keep their trade links intact, as their current deals with Russia indicate. The United States, Europe, and their allies need to prioritize consultations with the swing states on sanctions, digital currencies, and the future of the international financial order to ensure the longevity of existing global structures. The transatlantic allies’ fundamental interest is also to ensure that the swing states, in the course of their hedging, do not enable, intentionally or not, Sino-Russian efforts to establish a global environment conducive to their shared, autocratic agenda.

The Myth of the Monolithic “Global South”

by IAN O. LESSER

It has become fashionable to view today’s strategic environment as one characterized by sharper geopolitical competition and diffuse power. The Ukraine war, alongside longer-term concerns about China’s rise, has increased anxiety about eroding global norms and declining policy consensus. Some of this is reflected in the debate about definitions of “the West” and the possible consequences of growing “Westlessness”. Decades of post-Cold War experience lulled policymakers into assuming broad global alignment in international policy (rogue states excepted), but now new conflicts and strains underscore differences among international actors in their approaches to the most pressing issues. If transatlantic consensus cannot be taken for granted, global cohesion will be even more elusive. In the context of this study, the Global South includes some of the most compelling examples of swing states that may challenge consensus-building.

“Global South” is inadequate shorthand for countries across Africa, the Middle East, Latin America, and South and Southeast Asia. But the term has enjoyed a striking revival, especially as a way to describe key states outside the Western alliance system. The growing dispersal of economic power, with India, Brazil, and leading African countries gaining considerable global influence, has played a role in this. The rising countries of the south share features of scale, potential for rapid growth, and development aspirations. Their potential for foreign policy alignment, however, has waxed and waned, with the war in Ukraine posing new tests.

War in the North, Anxiety in the South

The conflict has cast in sharp relief questions about the nature and outlook of the Global South. It has also underscored the importance of national interests, values, and the role of history in shaping contemporary perceptions. Brazil, South Africa, and India are at the center of this maelstrom and are often seen as bellwethers for perspectives across the Global South, where there is no uniformity of views or policies toward the war or strategy toward Russia. But the positions of countries in the Global South share a number of features that may tell us much about how diverse actors in the international system will perceive future conflicts and the scope for these countries’ alignment with American and European policies (assuming a degree of transatlantic consensus, an open question in its own right).

Leaving aside countries such as Syria, Venezuela, North Korea, Mali, and others whose regimes rely heavily on Russian support, most countries in the Global South oppose the Kremlin’s war of aggression on legal and moral grounds. Respect for territorial integrity tends to be taken seriously, and UN General Assembly resolutions attest to this. Those voting with Moscow are clear outliers, although a significant number of countries are inclined to abstain. The conflict may be distant, but countries in the south are keenly aware of their exposure to its global consequences, particularly regarding food and energy security, and the risks to international trade and investment.

There is a growing sense of southern exposure to large-scale conflicts emanating from geopolitical clashes in the Global North, an ironic reversal of the post-2001 narrative about the West’s exposure to instability and political violence emanating from the south. It is unsurprising, therefore, that policymakers and opinion shapers in Africa, Latin America, and much of the Middle East view the deepening Western confrontation with Russia as a distant, troubling development to be held at arm’s length. Indeed, notions of equidistance and nonalignment have strongly influenced the post-colonial evolution of foreign policies throughout the Global South. They may opt to swing toward a Euro-Atlantic outlook on various issues, but their own interests dictate if they do. Understandably, they resent being forced to choose under conditions that may be existential for others but not for them.

Israel is not usually described as part of the Global South, yet it offers a clear example of this ambivalence. The country is fully aligned with Western condemnation of Russian aggression and has supported Ukraine with humanitarian and limited defence assistance. But Israel clearly could do more. The limits appear to be set by different views within Israeli society, with its large Russian and Ukrainian diasporas, and the desire to preserve the country’s freedom of action vis-à-vis Moscow in Syria and Lebanon.

The Return of Nonalignment?

A degree of nostalgic sympathy for Russia exists in some quarters across the Global South. This is especially true in parts of Africa and Latin America, whose support Moscow has keenly encouraged through regional media and targeted high-level visits. There is also a reflexive discomfort with views and policies set in the north, often by formal colonial powers. Even where bilateral cooperation with European and North American partners is well developed, as it is in South Africa, positive views of NATO are not a given. Cold War memories remain potent. China has been adept at exploiting this by promoting a sense of shared identity with the Global South, and the country’s development model retains its admirers.

But in their approach to Russia, many Global South actors have adopted an approach that may be described as functional nonalignment. In practical terms this has meant condemnation of the invasion of Ukraine but a reluctance to impose sanctions on Russia. Southern actors may be aligned with transatlantic and other like-minded partners on many issues while still being inclined to preserve economic and political ties to Moscow. To varying degrees, this approach is visible throughout the Global South. For some, a distaste for economic sanctions in general is part of their thinking.

Ambivalence Toward China

Some of the same sources of ambivalence shaping the Global South’s approach to Russia and the war in Ukraine are also evident in the longer-term and, potentially, more consequential debate on how they deal with China. The sense of development and policy affinity inspired by the original conception of the BRICS has not disappeared. But it is much less obvious 20 years on as Beijing has gone its own way. Today, economic interest is a far more important factor in African and Latin American policy toward China. Large-scale Chinese loans and investment, not least via the Belt and Road Initiative, have created a web that will be difficult to disentangle, even if there is a desire to do so. Competing connectivity initiatives, such as the EU’s proposed Global Gateway, are hardly on the same scale. Still, the Global South, like North America and much of Europe, has hardened its attitude toward Beijing as an economic and political partner. For countries such as Brazil, the ambivalence is unsurprising. China is Brazil’s largest trading partner and an overwhelmingly important consumer of Brazilian food and raw material exports. At the same time, China is widely seen as an engine of Brazil’s deindustrialization. Brazilian expert and official opinion largely aligns with European and North American partners regarding China’s dubious behavior toward intellectual property, digital governance, and human rights.

Why Choose?

A world of heightened geopolitical friction and animating conflicts holds the potential to reshape the economic and the security environment. Countries of the Global South are keenly aware of the challenges this may pose. The prospect of greater political conditionality in trade and finance— globalization by invitation—with sanctions regimes, friendshoring, and strategic decoupling would force uncomfortable choices.

Countries in the Global South may well swing toward more critical transatlantic views of Russia, China, Iran, and other revolutionary or dissatisfied actors on practical grounds or out of principle. But the Global South is most unlikely to align with the notion of a global struggle between democracy and autocracy. This ideological aspect of the Western foreign policy debate has only limited resonance outside the United States and Europe (and is not uniformly popular even there). As one GMF meeting participant put it recently, governments across the Global South are “simply not buying” the democracy-versus-autocracy competition.

A Matter of Engagement

The south is not monolithic. There is little uniformity of view on the leading issues animating current transatlantic debates on international policy. This brief assessment suggests a few lines of difference and potential alignment in policy terms. But there is one overarching concern likely to shape southern perspectives: fear that spreading geopolitical friction and conflict will distract the international community from addressing longer-term challenges to which the Global South is particularly exposed.

These include climate change, health, food security, migration, and development.

Countries across the Global South are highly vested in multilateral institutions, and many are adept at multilateral diplomacy. They will be wary of, and likely swing away from, unilateral or, in their view, “club-like” efforts emanating from Global North powers. This suggests that the style and structure of transatlantic activism on key issues may be as important as actual policies for shaping north-south convergence over the next decade.

Global Swing States in Focus

Brazil: A Voice for All?

by WILLIAM MCILHENNY.

“Brazil is back,” says President Luis Ignácio Lula da Silva in reference to the quest for the influence and respect accorded a first-rank global player. Brazil has strengths that support such status but securing it requires pragmatic statesmanship, domestically and internationally, also of the first rank.

The country sees itself as an adroit hedger that protects its interests by avoiding taking sides. It seeks the revision of global architecture to favor inclusiveness, more regional integration, and greater engagement with a broad spectrum of countries with little need for ideological litmus tests, including one for democracy.

Brazil advocates robust partnerships to help address the world’s biggest problems, particularly global climate change and deforestation, food security, and inequality. This approach dovetails with, and may be key to, Lula’s most daunting domestic priorities. It may also encourage pragmatic partnership preferences and choices for an internally polarized country, although the incumbent foreign policy leadership favors greater strategic distance from the big Western powers. For the United States and Europe—no less than for Brazil—the situation demands a willingness to be patient and accept compartmentalized engagement on these issues.

Brazil’s substantial assets confer leverage. Its size; sophisticated human and technological capital and productive capacity; economic importance; regional military strength; vast agricultural, mineral, and energy production; enormous potential to fight climate change; sophisticated diplomatic apparatus; and a resilient, if stressed, democracy cumulatively underscore the country’s capacity to help address global priorities.

Brazil seeks to deepen its engagement on trade, investment, security, and technology issues with players as diverse as China, the EU and its member states, the United States, Russia, and India through “strategic” (as Brazil describes it) alliances and partnerships of varying depth and impact. Brazil rejects that its choice of partners must be mutually exclusive. At the same time, it realizes that other countries’ inclinations toward conditionality can impose opportunity costs and that its interests may require hard choices that will disappoint some partners. In this regard, Brazil epitomizes the characterization of the Global South laid out previously in this report.

Playing It Safe

Brazilian logic on security policy, especially concerning Ukraine, exemplifies the disappointment partners may feel. Loath to choose sides after Russia’s invasion, Brazil reluctantly voted for the initial UN Security Council resolution condemning the Kremlin’s move but declined to support sanctions. Despite Brazil’s large ammunition exports, Lula rebuffed entreaties from US and German leaders to sell some to Ukraine. Yet Brazil was the lone BRICS state to vote for the February 2023 UN General Assembly resolution demanding a Russian withdrawal. Brasilia seeks to position itself as a peace broker, although Western governments doubt its impartiality as it seems to seek common cause with China.

Brazil has had preferred military ties to the United States and Europe (notably France), also its leading import and export partners. But its major non-NATO ally (MNNA) status has not precluded other, if less substantial, military agreements, exchanges, and training exercises with many nations, including China and Russia.

Open for Business

Brazil, the world’s 12th-largest economy, is a top trade player with enormous production and exports of iron ore, soybeans, and beef, and major exports of commercial aircraft and other high value-added goods. Traditionally skeptical of free trade agreements (but possibly on the cusp of ratifying a highly significant, long-gestating pact between the EU and the Southern Common Market (MERCOSUL)), Brazil retains substantial tariff and nontariff trade barriers.

China is Brazil’s top trade partner, followed by the EU and the United States, but the $100 billion relationship with the United States is the most diversified of the three. Brazil seeks to upgrade its Chinese trade links and make them similarly wide-ranging. They are now profoundly lopsided toward raw material exports.

The United States leads foreign and direct investment in Brazil, according to the country’s central bank. The $128 billion that Americans have poured in exceeds that of even the EU. China has invested more than $66 billion since 2010, especially in infrastructure, and has become a critical pillar of Brazilian economic growth. Brazil welcomes this development, as it assiduously seeks increased investment, including from Russia (in energy). The regulatory environment for investment has long tacked more liberal than for trade, even if accompanied by a host of sectoral restrictions, such as those involving rural land.

Russia continues to be a major source of Brazilian agriculture’s vital fertilizer imports, supplying about a quarter of them. Trade links in other sectors, however, have suffered. Brazil may not have joined in moves to isolate the Kremlin, but the country’s large multinational firms, such as aviation giant Embraer, generally moved quickly to withdraw from Russia following the imposition of US and EU sanctions.

Regarding multilateral institutions, Brazil’s profile was growing in the World Trade Organization (WTO), where it had sought to forgo special and differential treatment and supported EU efforts to create a working group on reform. Lula’s accession to power, however, leaves unclear the tenor of Brazil’s future engagement there, and of its previous interest in membership in the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. This may be one sign of a more revisionist Brazil that seeks to dilute Western influence and strengthen alternative global structures.

China Calling

US and European government and industry are valued partners in technology infrastructure, particularly for military and security purposes. Brazil’s information and communication technology market is among the world’s 10 largest, valued at more than $50 billion, and it is growing as Lula pledges that his government will spur a digital industry revolution.

US and European technology and science cooperation is anchored in bilateral agreements, some of which are highly specialized and facilitate important technology transfer and commercial partnerships. Meanwhile, China has an increasing role guiding growth in Brazil’s technology sector. Beijing is accelerating investment in key sectors such as renewables and telecommunications. Chinese companies have benefited from Brazil’s resistance to US pressure to exclude them from 5G infrastructure development, though government-issued personal communication devices are an exception. Brazil has a mature telecommunications policy and regulatory environment but generally does not share US security concerns about China’s role. At the same time, China’s cutting-edge technology and pricing advantages significantly bolster its companies’ competitiveness, despite growing concern over Chinese influence and its impact on Brazilian manufacturing.

In the aerospace sector, Brazil is already a standout, producing and launching satellites, and developing launch vehicles through various forms of cooperation with Russia, China, the EU, France, and Germany. Brazil also benefits from agreements and significant collaboration with the United States to start commercial space launches from the Alcântara Space Center, an area in which Brazil is especially keen for greater investment. Three of the five foreign companies approved to operate at the center are based in the United States. Brazil signed in 2021 additional agreements with space agencies of other BRICS countries for joint development of a remote-sensing satellite constellation.

The Power Game

Brazil defends a rules-based global order but continues to view traditional arrangements as skewed in favor of traditional powers, notably the United States. Brazil seeks to temper this by supporting new organizations and processes that transfer influence from Western to emerging powers. It believes closer alignment to China will advance this goal. In the meantime, Brazil works with other G4 nations on UN Security Council reform while seeking its own permanent seat. And its 2024 G20 presidency will test its capacity to bridge the interests of major powers and the transformational aspirations of the Global South. Brazil seeks to revive and strengthen the India Brazil South Africa (IBSA) Forum and the position of the BRICS and use them as tools to revise global governance. To expand its influence in finance and development matters, Brazil, as a founding member, is active in the Beijing-based Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank. It also plays a key role in the Shanghai-based New Development Bank. In March 2023, Lula secured the resignation of that institution’s Brazilian president and replaced him with a loyalist countrywoman, former President Dilma Rousseff.

In regional governance Brazil seeks to strengthen organizations and associations such as Community of Latin American and Caribbean States, MERCOSUL, and the Union of South American Nations (or UNASUR, which it just rejoined). Brazil believes that these groupings can help advance its own leadership and Latin American integration while reducing US influence in the region.

India: Tilting Westwards

by GARIMA MOHAN

India's muted criticism of the war in Ukraine, its close partnership with Russia, and a foreign policy that leans toward multipolarity and strives for strategic autonomy may suggest otherwise, but New Delhi is steadily moving closer to the West. Increasing tensions with China have awakened India to the need to balance strategic autonomy with aligning with like-minded partners on fundamental geopolitical issues. India has consequently diversified its partnerships in recent years, in part by strengthening its ties to the United States, Japan, France, and Australia. The partnership with Europe as a whole has never been as strong as it is currently, as the Indian foreign minister recently noted. India will still continue to pursue an independent foreign policy, but it is already a predictable partner for the West given the challenges it faces with China.

Seeking New Security Partners

India’s stance on Ukraine is not as publicly critical of Russia as the United States and Europe would like, but New Delhi does share Western assessments of the war. India is held back by an unwillingness to relinquish its partnership with the Kremlin primarily because the country views China as the bigger threat, and it wants to avoid a scenario in which an isolated Moscow forges an ever-tighter alliance with Beijing. Structural factors, such as dependence on Russian armaments, further constrain India’s room for maneuver.

China, unlike Russia, is increasingly a point of convergence between India and the United States, and the two countries are already closely aligned on Indo-Pacific security. They are not treaty allies though they are “moving towards a partnership that increasingly has some of the characteristics of an alliance”. The United States is a significant supplier of Indian defense equipment and India’s largest military exercise partner. The two also have bilateral agreements on logistics sharing and cooperate on intelligence, defense technology, and maritime security. They increasingly concur on strategic issues.

Although India supports a multipolar world order, declining US power or a move toward retrenchment would be a source of concern. Significant US involvement in the Indo-Pacific reassures New Delhi.

Despite those many US ties, France is actually India’s most important security and defense partner. Paris is India’s second-largest military equipment provider, trailing only Russia, and is key to India’s decade-long quest to reduce its dependence on Moscow. In addition, Indian and French national security advisers and defense ministers regularly consult one another, and other high-level government officials coordinate their positions on global issues.

India is also exploring joint weapons production with several other European partners and has stated its eagerness to work with the EU in the Indo-Pacific. On China, however, New Delhi is skeptical of European policy and considers European countries to be swing states.

Westerly Trade Winds

Since India walked out of Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) negotiations with other Asia-Pacific nations, its trade interests have focused on the West. New Delhi recently dispensed with its long-held reluctance to free trade agreements and is now negotiating several with the EU, the United Kingdom, and Canada, among others. The shifting stance comes as the United States recently surpassed China to become India’s top trading partner. The United States accounts for 11.6% of total Indian trade, with the EU in third place, trailing China, at 10.8%. The United States and the EU are also the top two destinations for Indian exports.

India’s economic approach clearly tends toward protectionism, though pressure to move away from that may be rising. The country is eager to attract US and European companies drifting away from China or seeking a China+1 diversification model.

Technological Upgrades

The United States and Europe are also India’s preferred technology partners. In fact, India’s recent push to strengthen European partnerships is predicated on greater technological cooperation, be it on green technology, defense technology, or renewable energy. India has also established its sole Trade and Technology Council with the EU. With the United States, India recently founded the Initiative on Critical and Emerging Technology (iCET), which will expand bilateral cooperation on artificial intelligence, quantum computing, space, defense technology, semiconductors, and telecommunications technology, including 5G and 6G. The idea is to broaden the collaboration beyond governments and include the defense, business, and academic communities. The United States, in a bid to insulate critical technology supply chains from China, eyes India as a partner for semiconductor production.

The Quad Critical and Emerging Technology Working Group is, for India, another important platform for cooperation, and one in which the country is diplomatically and bureaucratically invested. The payoff is handsome as the working group makes progress on the critical aspect of setting technological standards.

Certain Indian approaches and domestic legislation, of course, still diverge from those of the transatlantic partners, even if they have not hindered closer technological cooperation. This is particularly true for data protection and privacy. At the same time, India’s quest for self-reliance, including on e-governance and e-commerce platforms, has intensified since the Russian invasion of Ukraine. The conflict starkly revealed in New Delhi the dangers of overreliance on any one partner.

The Age of “Minilaterals”

India’s engagement with multilateral institutions and groupings, including the G20, the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation, and the BRICS, is another foreign policy mainstay. The country is also regularly invited as an observer to other gatherings, such as G7 summits, which New Delhi relishes. India consistently argues for reform of global governance organizations and for international representation, most prominently in an expanded UN Security Council, that more accurately reflects the changing world order. In this regard, as in many others, such as sanctions policy, India sides with its partners in the Global South. The American framing of global challenges in terms of democracies versus autocracies generates little resonance. New Delhi stays away from democracy promotion as a foreign policy instrument, and its efforts in that area are confined to building technical capacities and strengthening electoral institutions.

Still, India increasingly sees itself as a bridge between the West and the Global South. Its positions on many issues no longer automatically align with, say, its BRICS or G20 partners. Policy instead aligns more closely to that of other middle powers. The “minilaterals” that India has joined are the clearest evidence of this. Flexible arrangements, such as the Quad, are much more consequential and important to Indian foreign policy than other groupings. In fact, India’s engagement with the Quad continues to grow, despite Russian and Chinese objections, and is now deeper than that with any other format. Its various trilaterals, whether with France, Australia, Japan, or others, are geared toward achieving goals that have eluded traditional institutions, especially those in the Indo-Pacific.

Indonesia: Maintaining Pragmatic Equidistance

by AARON CONNELLY

With its long history of nonalignment, Indonesia is determined to continue its tradition of remaining aloof from great power rivalry and maintaining a pragmatic equidistance from Beijing and Washington. This does not exclude the possibility of cooperation with either when it serves Indonesian interests. But it does incentivize Jakarta to identify partners elsewhere —in Europe, Russia, or the Gulf—for the defense systems, trade and investment, and technology needed to ensure security, domestic political stability, and increased living standards for its 270 million people.

Still, a Bias Toward Beijing

Indonesian policymakers tend to view rising US-China tensions as the greatest threat to regional security. They work to manage exposure to the risks of alignment with either power by avoiding even the perception of it. Senior officials, however, tend to discount the threat that Chinese actions present to peace and security while they question the sincerity of US officials who portray American positions as deterrent rather than escalatory. This has resulted in slightly more sympathy for Beijing than for Washington on Taiwan, the US defense of which would depend on access to Indonesian sea lanes.

Jakarta seeks to quietly manage, without American assistance, a dispute in the South China Sea that involves competing Chinese and Indonesian claims. There is no desire to give Beijing a pretext to perceive the dispute as a proxy for US-China competition. But that does not mean Indonesia will stand idly by when its territorial integrity is at stake. The Indonesian armed forces (TNI) responded with shows of force when Chinese coast guard ships confronted them in 2016 and 2019, despite knowing that any dispute that resulted in casualties would have been difficult to manage.

The TNI were once heavily reliant on American weapons systems, but they diversified their defense supply chain in the 1990s. Following the imposition of US sanctions in response to human rights abuses, Indonesia turned toward Russia, Europe, the Middle East, and South Korea. Russia is no longer a supplier due to US sanctions, giving European manufacturers an opportunity to seize Moscow’s former market share. The TNI still aspires to acquire high-end American systems, but price and restrictions on technology transfer complicate any purchase.

China Lends a Hand

Two of President Joko Widodo’s trade and investment policies—related to constructing a vast transportation infrastructure network and to a series of raw minerals export bans—have made China Indonesia’s preferred economic partner. Beijing has financed many highly visible development projects, such as railways, roads, airports, and seaports, that have been political winners for the presdient, also known as Jokowi. The ban on raw minerals exports, particularly that for nickel, has also been a success. It spurred Chinese investment in processing facilities that have allowed Indonesia to move up the value chain. This fulfilled a long-term goal of Indonesian economic planners and defied warnings from Western businesses that the gambit would not work.

The Jokowi administration has also prioritized certain green industrial sectors, particularly batteries and electric vehicles, to boost exports. At the same time, the government has been reluctant to reduce its use of coal for electricity, much of which is produced by Beijing-financed power plants. The details of a Western-backed Just Economic Transition Partnership (JETP), which would compensate Indonesia for closing its coal-fired plants, are under discussion. But monitoring and implementing the decarbonization of the Indonesian economy is likely to be challenging and could create friction with donors in Europe and the United States.

The China-ASEAN Free Trade Agreement, which went into effect in Indonesia in 2010, and the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership, a free trade pact among Asia-Pacific states that entered into force this year, more closely bind the Indonesian and Chinese economies. Similar efforts with other powers lag. Indonesia has been negotiating a free trade agreement with the EU for the past six years, and the country is part of the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework for Prosperity talks with the United States, but these efforts are unlikely to conclude soon or in a way that changes the structure of Indonesia’s trading relationships. Jakarta’s dirigiste economic policies have made it a frequent target of industrialized countries’ complaints at the World Trade Organization, where it tends to align itself with the Global South. Indonesia’s large palm oil industry, which, the EU alleges, accelerates deforestation and climate change, has emerged as a particularly thorny irritant in the country’s relations with Brussels.

But the top investment priority for the Jokowi administration, now in its second term, has been the construction of a new capital carved out of the forests of Borneo, at a cost of $34 billion. The government intends to fund only 20% of the cost and rely on foreign investors to cover the rest. It has struggled to raise the necessary funds and, wary of the perception that it has become too reliant on China, has focused on attracting financing from Japan and the Persian Gulf. The government may still need to turn to Beijing, which would have significant implications for Jakarta’s geopolitical positioning.

No Worries

In the digital sphere, Indonesia has set the acquisition of advanced technologies at low prices as the priority. It has little concern for the implications of working with suppliers from countries that may pose a cybersecurity threat. In this sector, too, Chinese firms have emerged as partners of choice. Indonesian officials tend to dismiss evidence of the risks of working with them and cite documents leaked by former US National Security Agency contractor Edward Snowden to argue that China is not alone in spying on Indonesians. Regulators of digital services share neither their European counterparts’ concern for privacy nor their American counterparts’ concern for free speech.

Wary of the West

Regarding the international order, Indonesia advocates placing the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) at the center of regional diplomatic architecture, allowing the group of ten small states to host and chair discussions among the world’s great powers. Indonesia, along with several of its neighbors, is wary of initiatives that could dilute ASEAN’s influence. The Quad is one such initiative, as it is perceived as a forum in which discussions about Southeast Asia’s future occur without the presence of the countries that comprise the region.

Indonesia may be the world’s fourth-most populous democracy, but it identifies more closely with the states of the Global South than with Western powers. Jokowi has crafted an increasingly illiberal society by working with legislators to pass laws circumscribing free speech, while the police have used preexisting statutes to prosecute and jail popular advocates of political Islam.

Indonesian reaction to Western criticism of these trends is influenced by the country’s history and geography. Leaders of Indonesia, an archipelagic state that endured three centuries of Dutch colonization, have long worried that great powers might again seek to divide its many islands and seize their resources. In the Cold War’s early years, Western nations, including the United States, lent credence to these fears by seeking to foment separatist rebellions in resource-rich provinces amid ideological competition with the Soviet Union. The result has been an enduring sensitivity about territorial integrity and a suspicion of Western motives, particularly when issues of democracy and human rights are involved.

Saudi Arabia: A Triangle of Nonalignment

by KRISTINA KAUSCH

Guardian of global oil markets, the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia remains a key US security ally, even if Washington has recently questioned Riyadh’s reliability and commitment to the rules-based global order. Last October’s Saudi refusal to raise oil production to mitigate the energy crisis triggered by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine irked Washington, creating friction that is unlikely to dissipate soon. Still, Saudi Arabia and the United States are, and will remain, closely linked, even if the relationship is becoming more complex. The Saudi elite’s reading of the emerging order differs from Washington’s. Riyadh’s priority now is to balance its ties with its main security partner, the United States, with those of its main trading partner, China, and its key OPEC+ energy partner, Russia.

Slick Policies

Saudi Arabia holds the second-largest share, or 17%, of the world’s proven crude oil reserves. It is the planet’s biggest hydrocarbon producer, generating 12.4 million barrels per day, on average, in 2020. Saudi economic dependence on oil, which accounts for 87% of the country’s total exports, is evident, and Riyadh’s dominant position in OPEC+ gives it a key role as a gatekeeper of stable global oil supplies and prices.